Last fall, Venture Beat was recommending that businesses begin to develop their voice user interfaces (VUIs) in order to be ready for a public increasingly comfortable with speaking to their devices. In their view, those most likely to immediately benefit from doing so were the automotive industry, those working in customer service, real-time interpretive and translation services, and services targeted to the visually impaired.

You may well be aware that developments in the use of voice-driven activities have been accelerating in the past 24 months. In the spring of 2016, ReCode announced that voice-first user interfaces had gone mainstream, publishing an initial study of how Amazon Echo, Apple’s Siri and OK Google were used by 1,300 early adopters. Later that same year, Ad Age ran a useful overview of the various voice initiatives emerging from Google, Amazon, Apple, and Microsoft. Despite the speed with which these things change, the piece is still worth a reader’s time.

A 2017 article in IEEE’s Spectrum pointed to increased progress being made in voice recognition, noting that word error rates were well under 7%. That improvement was attributed to a fortunate convergence of multiple technologies – processing power, mobile devices, artificial intelligence (AI) born of neural networks, and more.

In 2018, Google has happily bragged that the usage of its Google Home has increased exponentially over that seen in 2016 as owners, “controlled more smart devices, asked more questions and listened to more music and tried out all the new things” that the system made possible. At this year’s Consumer Electronics Show, they assured reporters that voice controlled assistants would save consumers more than 15 minutes out of their morning routine, primarily because Google Assistant was empowered with the capability of performing more than 1 million actions. Apple’s HomePod is expected to release on February 9. Engineering students at Arizona State are being primed to work on developing skills for Alexa, living in the first voice-enabled dorms equipped with such devices. If that information is insufficient to persuade readers that this is where we’re headed, late January saw Fast Company trumpeting the introduction of the first graphical AI interface for developer use in supporting this form of engagement.

But how does this form of engagement prove itself useful in the context of this community? What happens if a researcher wants to turn to voice-driven services to seek out useful content in the form of monographs, journal articles, or even content from the open web? Last year, Scholarly Kitchen Chef, David Smith of the IET referenced one developer’s foray into creating such a skill for Amazon’s Alexa — one intended to scan Machine Learning literature updates on arXiv. Clearly, the tech-savvy are already considering the possibilities.

It is decidedly sophisticated stuff and those working on human-machine interactions are still working out the parameters for voice-driven interfaces. As numerous user experience (UX) professionals have pointed out, designers haven’t had time yet to develop the general use conventions for voice that are established for graphical interfaces. To be clear, the delivery context is that of an eyes-free voice assistant. While some voice-driven devices have screens, Voice-First developers are primarily focused on delivering audio response. Google provided version 1.0 of their Evaluation of Search Speech Guidelines just last month as a means of providing some sense of how this form of response should be handled.

The Guidelines recommend that developers evaluate the voice output on the basis of information satisfaction (that is, whether the response from the system exactly includes the information requested). A second criteria is the length of response; responses delivered through audio are expected to be shorter than responses that may be scanned on-screen. Thirdly, the response must be grammatically correct and finally, the delivery should be evaluated for appropriate elocution (diction and rhythm).

If you’ve ever searched Google using the OK Google function, you may have experienced a range of such responses. An unthinking user (possibly me) might casually activate a voice search with the word biography followed by the name of Jane Austen. The output wouldn’t be particularly detailed but, strictly speaking, the system’s spoken response would have satisfied any off-handed information need by reading out from a Wikipedia entry.

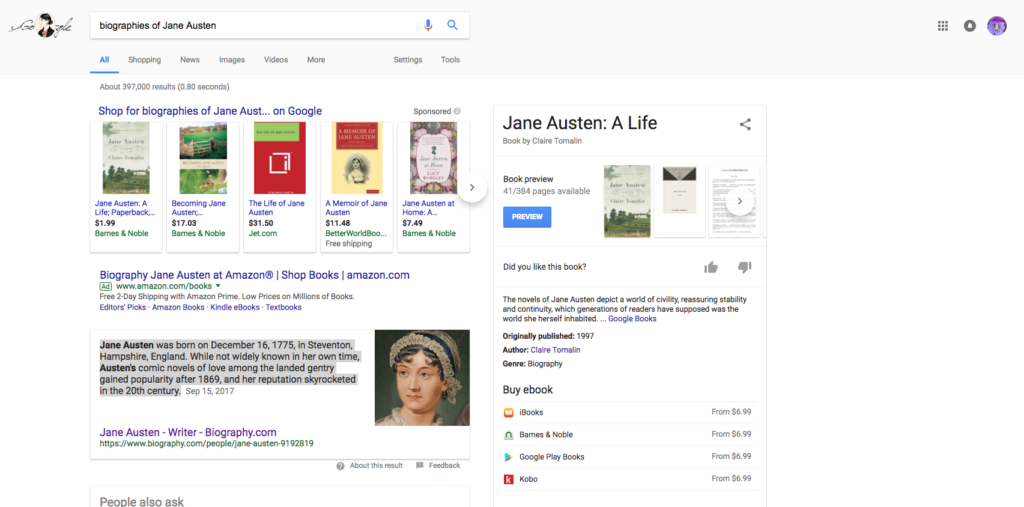

Offer a slight modification to that query by pluralizing biographies and the system offers images of the covers of published biographies and the same mechanized voice reads a (different) paragraph on Austen’s place in history from Biography.com (see the highlighted paragraph in the screenshot below).

Increasingly specific, the user might ask for a “bibliography of biographies of Jane Austen”. Under those circumstances, there is no voice response and the user is presented with an on-screen result of a not-entirely-wrong link to Amazon where third-party sellers offer David Gilpin’s 1997 work, A Bibliography of Jane Austen. Because the AI might not be entirely confident in its own response to that query, on the right hand side of the screen is displayed an alternative response — a link to and a cover image of Claire Tomalin’s best-selling Austen biography, still in print.

GIGO (Garbage-In-Garbage-Out) is the rule for computer interaction, and I recognize that the queries submitted are not a particularly fair test. However, it is a legitimate indication of human behavior. My unexpressed intent (one that a skillful reference interview would have elicited) was to find out which recent Austen biographies were considered by experts to be the most authoritative. Some part of my brain thought a course syllabus, a bibliography, even a LibGuide on Austen might pop up in a search and provide an indication. In speaking the query aloud, I did not bother to think about query structure beyond the vague concern as to whether the system would need me to verbalize quotation marks around the author’s full name.

As an aside, running a Google search on an historical figure has improved due to the past decade’s attention to entity extraction and linked data. Insofar as I can tell, however, voice interaction sets it back. A then-and-now example is available. Ten years ago, I was searching for information about the 19th c. illustrator, Louis J. Rhead. Even when information was input correctly (spelling, search syntax, etc.), my search documentation indicates that Google’s results kept rendering the surname as either read or as head. Running the same search in 2018, Google was able to serve up a knowledge graph card when I typed in the artist’s name, but when I submitted the same query by voice, spelling out the surname to avoid any issues of homonyms, the system failed. AI rendered the proper name as Luis Jarhead.

And I was really testing only one of the multiple forms of voice-driven interaction. These include:

- Command based input (instructing Alexa to switch on a light.)

- Speech to Text (dictation of the search query into Google)

- Text to Speech (providing support for accessibility)

- Conversational (interacting with chatbots)

- Biometric (voice recognition for personal identification)

This is why working with voice-driven interfaces currently requires a focus on programming specific Skills (for Alexa) or Actions (for the Google Assistant). Responding to tightly focused commands or questions — setting an alarm or specifying the number of teaspoons in a tablespoon — is manageable by current systems, but queries with a more ambiguous intent represent a challenge. “What is the weather” is a problematic query whereas the alternate “Is there rain in the forecast” is less apt to be misunderstood.

Just as I appreciate the engineering achievement behind a displayed knowledge graph card, I am willing to give a respectful nod to Google for the effort applied to satisfying my voice-driven search. The response to my original query was a succinct, grammatically-correct paragraph on Jane Austen, delivered with acceptable speed and elocution in a clear (albeit mechanized) voice. At the moment, we’ve established a functional baseline for voice-driven interfaces, but not more than that.

Where should the emphasis be in the next three to five years? Should information providers be thinking about enabling voice driven interaction with devices or is that too modest an ambition? The constraints on resources being what they are, what if I want to query WorldCat by voice? Which university library within 25 miles of my home holds this title? Google can tell me that the library is open at this hour and that the traffic between my home and the university is sufficiently light to make it a relatively quick trip. However, the data that Google holds cannot advise me as to whether the desired title is currently on the shelf. If voice interactions are going mainstream, isn’t this the type of service users are being led to expect?

Of course, WorldCat only indicates whether a particular title is held in a library’s collection, not its circulation status. For that, we’d need AI drawing from data gathered via shelving sensors or service exits. The point is whether we are thinking about services that ordinary users will view as viable, useful and non-intrusive. Are content and platform providers thinking about how best to engineer artificial intelligence services that can be tapped with just a voice command? (For the record, some, like Highwire, are brainstorming ideas.)

In the meantime, I have a request. Would it be possible for a voice-activated device to begin responding to me in the tones of the lugubrious butler on the ‘60’s television series, The Addams Family? Lurch always indicated his readiness to serve via the deepened voice of actor Ted Cassidy, seeking confirmation with You Rang? That’s what I’d like users to experience in the short-term. Because, as Georgia Tech professor Ian Bogost has recently noted, Alexa is Not a Feminist.

Discussion

6 Thoughts on "What Will Scholarly Information Providers Do About Voice User Interfaces (VUI)?"

Excellent post Jill, thought provoking for sure, as was David Smith’s original Alexa post too, great to hear there’s some brainstorming and serious thinking going into this area, Lurch/Ted Cassidy and all 😉

We had an interesting round-table session with ‘Alexa’ at one of our regional SSP Philadelphia meetings, she kept time well, and was reasonably funny on the joke side … but there’s more I’m sure can and will be done … look forward to the next installment …

There was an article in Slate recently that looked at how users began to work with Alexa once the novelty had worn off (see: http://www.slate.com/articles/technology/future_tense/2017/12/what_life_with_an_amazon_echo_is_like_after_the_novelty_wears_off.html?wpsrc=sh_all_tab_tw_top). This is a background tool that just by being “handy” becomes well-established as a useful capability. But I also think it says something that there was press coverage emerging from CES this year indicating that Acer and Asus were both going to be bringing voice assistants to the next generation of their laptops. Is it easier to dictate our memos than to type them? (No, not as long as the system insists on rendering the recipient as Luis Jarhead rather than as Louis J. Rhead.) But why use a keyboard if the system becomes able to recognize Rhead as a last name from among my contacts and can capture the gist of my message?

I will admit to being a “voice UI resistor” in my personal life (though the voice UI in my car is decent, except when I ask it to play a particular song from a classical catalog and then it is really close to random). But I have seen the data from Google that had led HighWire to do more work on mobile search (via and with Google Scholar) because the gap between “commodity” search — which is about 50% mobile — and “scholarly” search — which is only about 10% mobile — represents an opportunity for growth. Google tells us that mobile is new not transferred searches.

I would imagine that voice is even more mobile than mobile: it is new queries, probably taking advantage of the unique characteristics of when and where voice (for input and for output) can be used when even mobile devices might be out of bounds. So even when we might say “nobody would want to have a scholarly article or chapter read to them” we should recognize that a voice query and a highly targeted answer (not an article but a title or abstract or assertion from an article) might be what the user needs to move on, or to mark an article to drop in their database.

We just finished a two day workshop on AI that was held with editors and publishers to explore the best AI opportunities for the editorial workflow — so we didn’t even get to talk about the research-literature-sifting part of the workflow. That will have huge opportunities and with natural language processing will probably move along rapidly.

It will be interesting to hear the voice synthesizers read some research-article titles! I suppose someone will find the same humor in that that Gary Trudeau found in the early Apple Newton interfaces that he spoofed in Doonesbury (or were those real?). But those will be followed by useful results pretty quickly, just as early GPS navigation (“recalculating”) was followed by Waze.

Asking whether a particular resource is available in a library (whether that resource be a virtual reality headset, a data visualization tool or a reference book) would seem to me to be a fairly basic type of query that users might want to satisfy via a voice driven interface. Meaningful responses to more sophisticated inquiries of the literature might take longer to achieve, but the expectation is certainly being created in a rising population of users.

Yelling into one’s phone while navigating between car and building is pretty normal for any professional these days. I am sure that the recent idiot commercial may have raised a few eyebrows, but most of the librarians I know have far more serious matters on their mind. System surveillance, protection of patron data, funding, preservation issues, just to name a few. I suspect that ad agency has exhausted their creativity for the “What’s in your Wallet?” campaign.