The announcement of Plan S by 11 European funding agencies has rocked the scholarly publishing community.

In a nutshell, these funders (and others that may join them) are banding together to impose Open Access (OA) publishing on their researchers. Most contentiously, the funders plan to cap the Article Processing Charges (APCs) that they are willing to cover, making it impossible for their researchers to publish in journals that charge relatively high amounts. On the journal side, those with APCs above the cap must either accept more (i.e., lower quality) articles or cut expenses by doing less review and editing. A CC BY license is required, and publishing an OA article in a hybrid journal is also apparently banned, such that these funders’ researchers are effectively unable to publish in over 85% of existing journals.

If other funders get involved, there’s a possibility that they’ll use their collective influence over researcher behavior to ram through major changes in how we fund peer review and publication. The current focus of the discussion is on APCs (i.e., charges applied only to accepted articles), but seeing as we’re taking a hammer to the whole system we should contemplate some alternatives too.

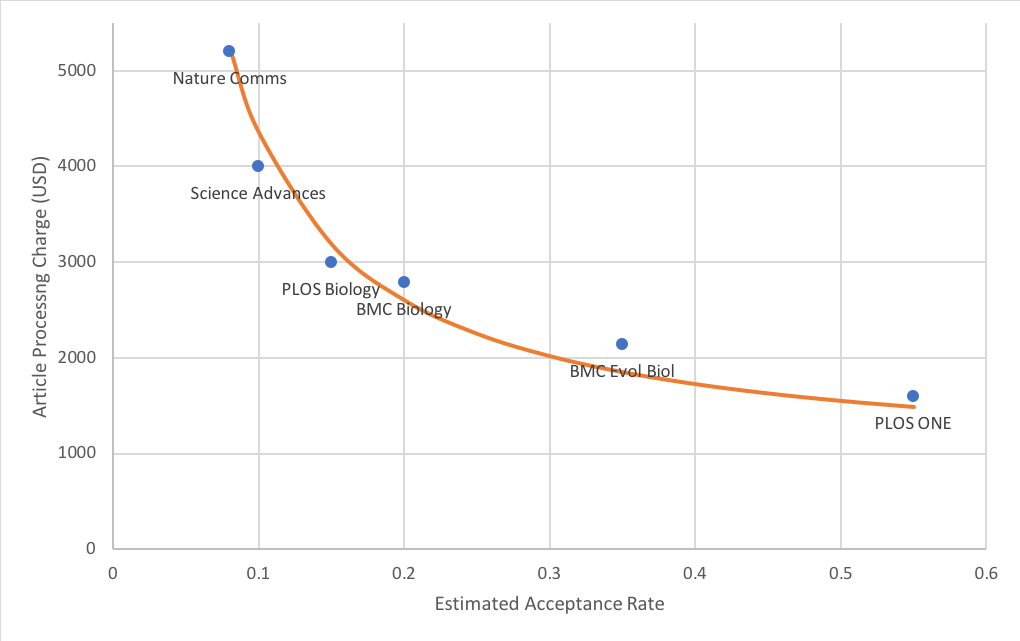

Why? APCs have the unfortunate feature that the authors pay for the assessment of all the other submissions that ended up being rejected. Manuscripts rejected from multiple OA journals thus contribute to the APCs of several different authors. Is it fair for authors of good articles to pay for the peer review of others’ lower quality work? Moreover, journals that do lots of peer review to find one acceptable article have higher APCs, as illustrated by the figure below.

*acceptance rate estimates from public statements and informed guesswork

*acceptance rate estimates from public statements and informed guesswork

While these are rough estimates, the fitted line is APC = 850 + 350*(1/Acceptance Rate). This choice of equation is not a coincidence: first, the inverse of acceptance rate represents the number of articles the journal has to assess before it finds one that can be published, and $350 is a decent ballpark for the cost of a round of peer review (e.g. $250 in 2011 [=$280 in 2018] from here, other estimates here).

The $850 represents an amount that for these journals (presumably) covers the costs associated with the accepted article (typesetting, proofing, hosting, etc.), along with the overheads associated with all the other things that publishers do. This amount may not be accurate for some journals – for example, PLOS Biology is said to run at a deficit at its current APC and is subsidized by revenues from PLOS ONE. But bear with me.

Breaking down an APC and how it relates to submission numbers and acceptance rates suggests another way to cover publication costs: a submission fee of $350 and a publication fee of $850 would generate the same revenue as the current APCs at these journals. (This approach has been suggested before, see here, here, and here.)

Most importantly, this fee structure means authors of accepted articles only pay a total of $1200 for publication, no matter how selective the journal. The fee would be $1200 for PLOS ONE and $1200 for Nature Communications. Even if an article is rejected from two journals before being accepted at a third, the total cost is $1900, which is still less than a typical APC.

This solves one of OA’s thorniest problems – how to run a high-quality, highly-selective journal without charging an enormous and impossible APC. The proposed fee structure even works for a journal with a 1% acceptance rate: a $350 submission fee and a $850 publication fee would equate to an APC of $35,850, which matches Sir Philip Campbell’s famous/infamous estimate that Nature would charge $30,000 to $40,000 for an OA article.

The big obstacle to adopting submission fees has always been first-mover disadvantage: authors don’t particularly like the prospect of submission fees and may favor journals that don’t charge them. Any journal introducing submission fees thus risks deterring authors. Interestingly, this didn’t seem to be the case at the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, where the introduction of a $250 submission fee led to a fall in low quality submissions, but the volume of higher quality articles remained steady.

If Plan S becomes a reality then ‘business as usual’ goes out the window, as publishers will find themselves scrambling to ensure that as many journals as possible are a) Open Access, and b) charging an acceptably low APC. One or more publishers opting to achieve (a) and (b) by introducing submission fees would affect so many journals that the first mover disadvantage becomes a non-issue.

As one might expect, having submission fees paid directly by funders would also significantly mitigate the first-mover effect, and helpfully the direct payment of publication fees is already part of Plan S.

The introduction of submission fees also affects submission patterns, most notably by steering away articles with only slim chances of acceptance. This effect would change the calculations in the figure above: fewer low quality articles arrive, so acceptance rates rise and hence reduce income from submission fees. However, a drop in submissions also means a drop in costs, as those weak articles no longer need to be processed through the system.

This effect on submissions should be more pronounced for a single journal introducing submission fees when their competitors did not, as authors can take their speculative submissions to the no-cost journals. However, if Plan S (or its equivalent) prompts the widespread introduction of submission fees, authors may not easily find a suitable journal that does not charge fees. Since they need to submit their article somewhere to get it published, the decrease in submissions may be smaller than feared.

A drop in submissions is not fatal for the submission fee math – even a 30% fall can be accommodated by raising the submission fee to $500, or by raising the submission fee to $400 and the publication fee to $1100. Journals would adjust their submission fees within some reasonable range depending on their brand perception, current levels of submissions, and a desire to remain competitive with other journals in the field. Journals with high fees may even be able to signal the higher quality of their review and publishing process.

Submission fees have other useful properties. First, they are ‘pay as you go’ for peer review: they penalize authors who submit low quality articles over and over to different journals, and reward those who prepare their work to a high standard and submit it to the most appropriate outlet.

Similarly, submission fees counteract the perverse incentives created when authors receive financial rewards for publishing in high impact journals, which is a major driver for inappropriate submissions. If they had to pay each time, would as many authors take a wild stab at getting their incremental work published in a top journal, then working their way, journal by journal, down the Impact Factor rankings until they reach an appropriate level?

Submission fees also bring peer review into line with lots of other services that cost money regardless of whether you succeed or fail, such as professional exams or even dental check-ups. Viewed through this lens, the ‘no win, no fee’ approach of APCs seems like an anomaly.

Clearly, there are many other aspects to consider (particularly unintended consequences), but if the funders are going to force a change in the financial structure of peer review and publication, we should give submission fees serious consideration: they’re a logical way to cap the cost of Open Access while maintaining the current ecosystem’s ability to filter articles by perceived importance.

Discussion

22 Thoughts on "Plan T: Scrap APCs and Fund Open Access with Submission Fees"

Interesting.

Another outcome might be that researchers will be incentivized to submit fewer papers to keep submission costs down. So less salami slicing of work? Less work for peer reviewers?

In a perfectly working market (along the lines of: the consumer knows exactly what the perfect product for their needs is and buys that and only that) rejection rates would tend to 0? Even in a less than perfect market would the rejection rate lose value as a signifier?

Is one plausible outcome that peer reviewers’ roles will be less about advising accept/reject and more about being partners – critical friends – in the final outcomes from a piece of research?

Unless I misunderstand the Plan S declaration, an APC cap doesn’t mean that Plan S funders won’t support publishing in a journal that charges more than the cap. It just means that they will cover up to the cap. This is an important distinction. The author is not forbidden from publishing in journals that exceed the APC cap. S/he can decide whether being published in a more expensive journal is justifiable using other funding sources (other grants, department, even personal funds).

Your argument and proposed solution wrongly assumes that this is a fund/no fund scenario, meaning, publishers either have to play along (and change their business model) or opt out. Using your market analogy of professional exams or dental check-ups, a funder (insurance provider) can cap service payment. If the client wishes to use those services, s/he is free to pay the difference. Alternatively, a service provider can negotiate prices with the funder.

While I’m supportive–in theory–of submission fees, this is a very complex market and the unintended consequences can be worse than the intended solution.

But will more than a handful of researchers have access to money to pay for APCs from non-Plan S funders? I doubt that departments will be keen to shell out an extra $3000 for a Nature Communications article when a Scientific Reports one would have done just as well. That leaves researchers to pay out of their pockets.

There’s always unintended consequences, even from sticking with APCs. If Plan S becomes reality, then everything will be in flux anyway.

I’m puzzling through the process of how this would work. I just don’t see this as going well. E.g.,

Researcher: Hey, I was accepted into Nature Communications! Can the department help me with the APC?

Department: Nah, Scientific Reports would be just as good and has a lower fee. Retract your submission from Nature Communications. Let us know if you get into Scientific Reports – good luck!

That’s long been a concern for author-pays APC models. Your university gets a block grant from RCUK for APCs, so you’ve got a set amount to spend. How do you divide that up among authors at your institution? Does the graduate student in a junior faculty member’s lab get as much as the big name senior professor? What sort of review panel should you have to go through to decide where you’re allowed to submit your paper?

What happens if an author sends the article to 10 different publishers. The total cost to the funder becomes $3,500 which is more than the APC.

It seems to me that the entire problem with the APC market is it assumed that there is a free lunch! And we all know what happens when one assumes.

Additionally, we now have funders taking on the role of censors. As a community do we want economic coercion?

So much remains to be revealed about discussing Plan S but something that I found a bit surprising was the notion that the caps were intended to be temporary. E.g., “The intention is to operate an APC cap for a period of time, then to remove the cap, says Robert-Jan Smits. Will it just create a race to the top? The clever ones will be those who offer high quality below the cap #Plan_S #coasp10” https://twitter.com/rschrobUK/status/1042043859457458176?s=19

Personally I’m not convinced the large publishers or those with high IF will be scrambling. But, it’s definitely hard to know!

I doubt that Nature Communications will lower its publication fees even when it charges submission fees.

Tim, I read this as a provocation rather than a proposal. You reveal in the starkest terms how the insistence on making scholarship free to read can make it more –likely prohibitively–costly for the scholars. Setting aside the very real questions across the board of furthering inequities in who can publish where, and how publication decisions are made for every discipline, it’s always been farcical to think that author –or aspiring author– pay will work for the humanities.

Humanities publishers provide a service by reviewing and in the process enhancing scholarship. (Don’t @ me, yes of course I know it doesn’t always work.) They do that for all submissions (with exception of clear lack of fit with the journal)– so everything, in theory, improves, not just what is published.

A particularly frank example from my own field is in an essay for the Chronicle, where an early career scholar describes the value of the review process for getting feedback on her book manuscript:

“I’ve adopted a strategy of recasting my chapters as journal articles — a process I’ve come to think of as “the revise-and-resubmit route to writing your book….That route involves submitting your book chapters as articles to the absolute top journals. Your goal: to get a revise-and-resubmit letter with reviewers’ comments that can help you conceptualize the broader argument you should be making in the book. I took this approach, not because I hoped my articles would be accepted (though that would have been nice) or rejected (I was almost sure they would be), but because I’d gotten to the point where I wanted someone to read my work in detail, and comment on it in writing.” (https://www.chronicle.com/article/Revising-the-Terrible/235872)

So, per your post, shouldn’t the user, in this case the scholar, pay for these services?

I still don’t think so. The ultimate beneficiary is the entire scholarly field. That’s where the contribution is being made, the reviewers’ time, the editors’ (extensive) time in (summarizing and guiding the revision process and) assessing whether the piece will be published, and of course the scholars’ time and efforts, too.

But also, the cost for every submission of what the journal staff expends in time and expertise would be impossible right out of the gate. (https://blog.oieahc.wm.edu/what-does-it-take-from-submission-to-publication-at-the-wmq/) Without grant-funded labs? With the state of even the largest humanities research budgets? (In my department, we have the luxury of around $1,500-2,000/ yr– and it is a wonderful benefit, many departments have $0).

I see this as less a “provocation” than a reaction to policies imposing author-pays methods for publication. Your arguments are all completely fair and accurate, but could just as easily be applied to APCs rather than submission fees. The idea here is that if you’re going to force everything into an author-pays model, then by including submission fees you 1) reduce the APC rates, and 2) you create a system that allows high-quality, high-rejection journals to continue to exist without charging an outrageous APC.

But this proposed adjustment only matters if researchers are forced into an author-pays world, which is not being argued for here. If you are going to mandate that, then maybe there are better ways to do it than either super-high APCs or capping APCs and getting rid of quality review efforts.

Still another example of how conditions in STM journals generally differ from SSH, which has its own problems, to be sure.

“Plan T” is the most coherent solution I have seen put forth to this endless author pays vs. reader pays debate (i.e, OA vs. subscription model). Yes, there are possibilities for unintended consequences. Trust in the publisher not to take advantage of authors through excessive desk rejections or other ingenious misbehaviors will be key. However, Plan T makes a lot of sense and could address a lot of inequities and unsustainable other models. Seems like the uptake will depend on a publisher picking a title to give a go with, and fair pricing that is attractive to authors. All this “funder pays” discussion overlooks the fact that in some fields, the “funder” is the author’s personal funds.

Great post. I hope it gets uptake. Maybe it should be called Plan V.

Submission fees are already used in some disciplines, especially in business studies. See figure 18 in this OECD working paper from 2016.

Boselli, B. and F. Galindo-Rueda (2016), “Drivers and

Implications of Scientific Open Access Publishing: Findings

from a Pilot OECD International Survey of Scientific Authors”,

OECD Science, Technology and Industry Policy Papers,

No. 33, OECD Publishing, Paris.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5jlr2z70k0bx-en

I strongly agree with this proposal. This is not a radical or hypothetical idea: submission fees are common in finance and economics journals, and have been since the seventies.

The $350 fee proposed here is higher than most of those, but even higher fees are viable – e.g. the ‘Journal of Financial Economics’ charges $750, despite competing against equally prestigious journals with no submission fee. The ‘Review of Corporate Finance Studies’ charges a $1,000 fast-track fee. Both are highly successful.

A key point made by Mark Ware is that submission fees with discounted APCs could be trialled as an option, so there’s no risk to the publisher in trying. It’s disappointing that none of the major OA publishers have even tested this possibility.

I give sources on the above and related points on pp. 82-84 of:

Solomon, D. J., Laakso, M., & Björk, B.-C. (2016). Converting Scholarly Journals to Open Access: A Review of Approaches and Experiences. https://dash.harvard.edu/handle/1/27803834

Finally, someone talking some sense about business models in open access publishing. Thank you

Thanks Tim for an absolutely excellent article! I have wondered for a number of years now why submission fees are not more widely adopted as it makes for a much more logical OA model than one based on APCs only. It will improve the average quality of submissions, reduce the percentage of desk rejects, moderate APCs and improve behavior overall. Complexity and unintended consequences which may arise as a result of Plan T are equally likely to arise as a result of Plan S (which as of now sounds unfeasible to me) as well. So Plan T is definitely worth further consideration in my view and I hope your post gets wide attention.

It’s an idea that has been around for a while of course, and yes i agree has a lot of merit if the “first mover disadvantage” issue can be tackled. Maybe there is more of a chance to do that now than when we published this report on the topic back in 2010:

http://www.knowledge-exchange.info/event/submission-fees

You say “On the journal side, those with APCs above the cap must either accept more (i.e., lower quality) articles or cut expenses by doing less review and editing.” Another option would, of course, be accepting lower profit margins.

That may be possible for the larger, commercial publishers that generate significant margins, but is much less feasible for many independent and not-for-profit publishers operating at much smaller margins. If this is the economic plan that emerges, the big commercial publishers have the flexibility within those large margins to adapt, but it will surely wipe out a significant number of smaller, independent presses, and further consolidate the market in favor of the biggest commercial publishers.

Also worth considering that a cut in margins for a society like the one described here means a lower level of service to its members, the research community itself.