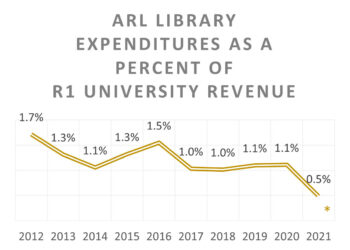

As was widely expected, eLife recently announced a move away from their 100% funder-supported business model to one where authors will be required to pay an Article Processing Charge (APC). And yet, as seems to be the case for several other highly selective, fully-open access (OA) journals, the chosen APC is too low to actually cover the costs of publication. Why are many OA publishers unwilling to charge enough to break even? Does this set unrealistic expectations for what it costs to run a top journal? And are there instead other strategies that might work better?

eLife has, since its founding, been in a position of privilege as compared with other journals. With access to the deep pockets of its wealthy funders, the journal has been able to run with few constraints, providing free high-quality services for authors and readers at no cost while at the same time offering generous salaries for editors and staff and investing heavily in technology development. As the leader of a major non-profit scientific society quipped at a meeting just after the launch of eLife, “it must be nice to be rich.”

At its launch, promises were made to move eLife to a sustainable business model after a few years. While that still hasn’t happened, the implementation of an APC is a move in this direction. But given the expenses that eLife incurs, the chosen APC, $2,500 per paper, only covers a fraction of their costs. A recent analysis suggests that a more reasonably sustainable APC level for the journal would range between $6,000 and $7,000.

Note also that if eLife was like other journals, it would need to pay off the original investment and startup costs, which would make the required APCs even higher. Startup journals are generally saddled with a large burden of debt as there are significant launch costs and most run at a deficit for the initial years. Those costs are slowly paid off once the journal starts to turn a profit. Since eLife has had all their initial bills paid, they don’t carry the red ink seen by a typical startup journal, which artificially lowers the APC they need to charge.

The $2,500 price is justified by eLife by dividing the costs for the journal into what they call “fixed” and “marginal” costs, defined respectively as costs that remain constant regardless of the volume of papers published, and those that vary with volume. It is suggested that $2,500 will cover eLife’s marginal costs, but as was the case with their annual report, the accounting here is questionable. “Article processing,” for example, is listed as a fixed cost, which seems contradictory. Regardless, the division between fixed and marginal costs here is nothing more than a shell game. The bottom line remains the bottom line, and if you divide your total expenses by the number of articles you publish and it works out to $6,000 per article, then that’s what it costs you, no matter how you choose to slice up the pie.

Why does this matter? It matters because the $2,500 chosen APC creates a false impression, that an amount this low is sufficient to support a journal that offers the high quality and strong level of author and reader services provided by eLife. There has long been a resistance toward high-end OA journals charging fees that actually reflect their costs. As the recent “Pay It Forward” report notes, APC prices are not set based on actual costs, but more on a fuzzy notion of what the competition is charging and what the market will bear. For hybrid journals, APC prices are artificially low, because they are subsidized by subscription and other revenue channels and would need to be vastly higher if required to stand on their own.

A leading humanities journal that I’ve worked with calculated that in order to maintain their current level of service to authors and relatively small margin, they’d need to charge $18,000 per article. Note that this is a journal where the top-tier subscription price for the very largest of institutions is around $300 per year, with most schools paying much less. Were they to move to a gold OA model, this would create a seemingly poor offering for universities, as the choice between paying for one author to publish one paper would be the equivalent to the cost of subscribing to the journal for the next 60 years.

I suspect there is also some advocacy strategy involved in setting these too-low-for-the-real-world prices. OA is often promised as a pathway to cost savings, a way to turn the market more competitive and to cut publisher profit margins. Admitting what it really costs to publish a top-notch journal undercuts these arguments. And so we end up with situations like PLOS’ high-end journals charging an APC ranging from $2,250 to $2,900 and losing money. The losses are covered by authors publishing in PLOS ONE, which remains highly profitable, and those profits are used to mask the actual costs of the other journals. When faced with increased expenses, PLOS chose to further burden PLOS ONE authors, rather than asking authors in the high-end journals to pay a larger share of their own expenses.

This creates an unrealistic expectation in the marketplace which may prove difficult to overcome. PLOS and eLife can get away with this because each has access to their own private pool of funds, either the tremendous profits of PLOS ONE or the enormous endowments of the Wellcome Trust, the Max Plancke Society and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. Most journals do not have such luxuries and so the models employed by either publisher are outliers that cannot be implemented by anyone else.

This lack of transparency ultimately does the cause of OA a disservice. If one really wants the world to move to a fully-OA publishing ecosystem, then one has to be realistic about the economics of such a system, and create functional and sustainable real-world strategies for long-term support. Offering a model that requires access to private pools of millions of dollars does not provide an example that will work for anyone other than the richest of organizations. If the market expects a top journal to only charge $2,500 per paper, and that’s not enough to support a top journal, then a shift to OA will not provide a sustainable future.

What’s frustrating here is that there seems a potentially likely path to making selective OA journals work financially: submission fees. The effects of submission fees are two-fold — by charging a fee for every manuscript submitted, the number submissions to a journal drops precipitously. All of the frivolous submissions of papers that are wildly out of scope or extremely unlikely to be accepted go away. This has an enormous effect on lowering costs and reducing an editorial office’s workload.

Second, submission fees cover the costs of rejection. This is a major driver of costs for highly selective journals. If all of your revenue comes from the papers you publish, then each paper published must pay for all of the papers that the editorial team spent time on yet rejected. If you’re receiving thousands of submissions per year and rejecting 95% of them, this can add up to quite a cost. But if each manuscript comes in with funds sufficient to cover the costs of its review and rejection, this problem is solved and published authors must only pay for the work that they receive directly.

If we are moving away from the selling of content to a model where we sell services directly to authors, this seems an obvious step. Rejected authors are still receiving a service which incurs costs that must be paid. It appears that eLife did consider instituting submission fees, but chose not to for the stated reason that, “given the variation in the feedback that is given to authors, we felt that a publication fee would be fairer.” How asking accepted authors to pay for the work done for rejected authors is “fairer” remains unclear.

The real downside of submission fees, and why we see so few willing to use them, is that they put a journal at a competitive disadvantage. If there are two nearly equivalent journals to which you could submit your paper, and one charges a fee and the other doesn’t, most authors will submit to the free journal. Paying a submission fee remains something of a gamble for an author, a measure of their confidence that they are sending their manuscript to the right and most appropriate journal. Because there is no guarantee of acceptance, making a bad call means that money is lost. A journal that implements a submission fee stands a risk of seeing papers go to the competition.

Further, many journals like to boast about their selectivity — a low acceptance rate is seen as a badge of honor. Because submission fees cause a large percentage of garbage submissions to go away, the journal’s perceived selectivity, shown by percentages of articles accepted, appears lower even though their standards remain constant.

While understandable for business reasons, it is disappointing that the strongest leaders in OA advocacy seem unwilling to experiment in this arena. It seems an obvious and practical way to give the field what it wants (and clearly there remains significant demand for high-end, high-service, highly-selective journals) in a sustainable manner.

Instead we are left with unrealistically low APCs that are not a widely reproducible means of doing sustainable business. These false expectations may do more harm than good in the long run, and slow the progress sought toward the spread of OA. It is better to honestly recognize the challenges such a move would require and seek realistic solutions, rather than making false promises that can’t be sustained. I would love to see publishers who are willing to conduct bold experiments take more chances with submission fees. If they prove acceptable to authors, then our ability to move toward OA without sacrificing quality would be greatly improved.

Discussion

25 Thoughts on "Can Highly Selective Journals Survive on APCs?"

Hai hebat betul ini gambarnya hingga bisa menyilaukan pandangan saya. i like

eLife isn’t the only OA journal with a “position of privilege” in financial terms. Many of the OA journals started by societies are subsidized by existing subscription journals and existing journals infrastructure, most of it paid for by other revenue streams (subscription journals, membership dues, meetings revenues, etc.). These subsidies are utilized because, as you point out, there is an unrealistic expectation that APCs will naturally fall into a certain range. If these OA journals had to carry all their associated costs, the APCs would be much higher, but they are subsidized in a manner not unlike eLife.

Low APCs trap OA in subsidy. From the perspective of a driving force, this hinders OA’s adoption and growth. From the perspective of a result, perhaps it shows that interest in the benefits of the OA approach isn’t sufficient to command a higher price, so subsidy is necessary.

One effect of this subsidy trap is that OA journals are highly subject to consolidation, as it is costly and inefficient to have the same infrastructure in multiple places. It seems inevitable that we will see more OA journals absorbed by larger publishers, and OA journals from larger publishers having greater financial success, in the coming years. It’s unclear that society-held OA journals will last, especially as their sources of subsidy come under pressure.

Being trapped in actual or de facto subsidy is ultimately a vulnerability, and the market should resolve these inefficiencies in time. The price to pay for low APCs will be consolidation, leading to fewer, large publishers taking over the OA space.

I strongly agree: submission fees are clearly a better way to fund selective journals than APCs alone.

On the risk you mention of deterring submissions, this risk can be eliminated by trialling optional fees, as suggested by Mark Ware. Authors could choose free submission and full APC, or submission fee and a steeply discounted APC. If no-one takes the option, drop the trial, with nothing lost.

Moreover, while one might assume that

“If there are two nearly equivalent journals to which you could submit your paper, and one charges a fee and the other doesn’t, most authors will submit to the free journal”,

we can test this assumption – look at economics and finance journals. To take an extreme example, in 2013 “Quarterly Journal of Economics” (impact factor 6) received 1,400 free submissions.

The “Journal of Financial Economics” was lower-impact (JIF 3.8), and charged an eye-popping $650 submission fee. You might think no-one would submit, but in fact they received 1,258.

Zheng, Y., & Kaiser, H. M. (2016). Submission Demand in Core Economics Journals: A Panel Study. Economic Inquiry, 54(2), 1319–1338.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/282941581

{ raw data: https://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.3423357.v1 }

This year JFE’s fee is $750! I estimate that they pull in around $7,000 per accepted article (much higher than any APC), despite refunding the submission fee to accepted authors. Their key selling point is very fast turnaround. Dozens of other journals in these disciplines charge submission fees, successfully competing against hundreds of other journals without them. So the deterrent effect is clearly not as strong as one might expect, even in the short term.

A number of biomedical journals with submission fees also hold their own against hordes of free competitors. The OA “Journal of Clinical Investigation” pulls in more money than any APC-only journal, courtesy of their tiny submission fee. For details and other sources, see my comment on pp. 82-84 of:

Solomon, D. J., Laakso, M., & Björk, B.-C. (2016). Converting Scholarly Journals to Open Access: A Review of Approaches and Experiences. Retrieved from https://dash.harvard.edu/handle/1/27803834

It is high time for an OA publisher to grow a pair and try this. Might I suggest you have a word to Oxford’s own “Nucleic Acids Research”?

Authors could choose free submission and full APC, or submission fee and a steeply discounted APC. If no-one takes the option, drop the trial, with nothing lost.

You’d have to be careful to strike the right balance though — lowering the APC would offset the gains you need to make by charging a submission fee.

Interesting info on the economics journals. I don’t know the field well enough to know whether the two journals are directly competitive and substitutive for authors but will take a deeper look, thanks.

It is high time for an OA publisher to grow a pair and try this. Might I suggest you have a word to Oxford’s own “Nucleic Acids Research”?

NAR is an unlikely candidate for this type of study, because it pulls off the rare feat of being both selective and high volume. Take a look at the number of articles published in the journal despite a high rejection rate. It is sustainable, due to this volume, at the current APC, so there’s no glaring need for that journal to experiment with ways to survive. I’d also note that at OUP we are supportive of OA and find it a valuable tool to further our not-for-profit mission, but aren’t actively advocating for a “flip” of the entirety of publishing to this model. The majority of what we publish is owned by research societies so we are limited in our ability to experiment on titles that we don’t own. For those reasons, we may not be the best candidates for bold, envelope-pushing experiments that put advocacy over business.

A discussion of submission fees needs to account for triage reviews vs. full reviews. All papers submitted to our journal first face a quick reading by the editorial team before going to reviewers. This eliminates manuscripts that are off topic or clearly unsuitable. As I liked to say, “I read ’em so you don’t have to!” Only then do we invest in a full peer review.

An increasing number of “return without review” decisions is indeed a burden on the editorial team, but I can’t see how we would justify a high submission fee for this service. In a sense, receiving too many manuscripts is a good problem because it lets you pick only the more promising for further consideration.

I think the idea is that one would charge a lower fee (or more likely refund a chunk of the submission fee) for articles that are desk rejected, then charge the full amount for ones that go through the full peer review process.

This is what ‘Journal of Financial Economics’ does. Desk rejection gives a refund of all but $100. I suspect that’s how they’ve been able to drive the total fee to $750. The ‘Review of Corporate Finance Studies’ does the same, and also offers a nosebleed $1,000 (!) fast-track review fee. I see it’s with OUP – perhaps the editors can talk some sense into your OA journals. I don’t agree that this is advocacy over business – the highest submission fees deliver more revenue than any APC. In OA, the ‘Journal of Clinical Investigation’ is self-sustaining, while ‘PLoS medicine’ needs a subsidy. I’d suggest it’s no coincidence that the discipline where submission fees are most common is economics.

I implemented submission fees at a selective specialty journal a few years ago. After the editorial qualms were overcome, and the process implemented, there was initially a desire to review everything thoroughly — after all, these people had paid a fee! But as time passed, it became clearer to the editors that paying the fee really wasn’t a way to put them under a new obligation, that their practices shouldn’t change.

After the submission fee was imposed, the quality of submitted manuscripts (based on internal manuscript scoring using levels of evidence) rose quite a lot, proving that the submission fee had eliminated a good bit of the dreck.

Another thing to keep in mind is that most journals experienced a 20% increase in submissions when online manuscript submission systems were implemented, simply because one barrier to submission — mailing the manuscript, which itself was expensive — vanished. Adopting online manuscript systems increased the editorial burden in and of itself. Putting a new cost barrier in place makes sense for this reason, as well.

We are a service industry, so it’s difficult to contemplate not doing everything possible if someone is paying, but the goal of a submission fee is to weed out the weak papers by creating an initial barrier, not to offer more services. In fact, offering more services after implementing the fee defeats the purpose. But, as I noted in an earlier post (https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2016/09/29/caught-in-the-middle-can-publishers-resolve-contradictory-expectations/), this editorial imperative (get as many papers as possible) is at-odds with the business imperative (be efficient). How this gets resolved will require someone giving up some preferences. Given the eroding economics of publishing and the surging number of submissions, it seems time for editors to erect some sea walls around their own operations.

Kent- Interesting that the quality went up after submission fees were introduced. We talk with a lot of CFOs who love the idea of submission fees (which we can support in RightsLink), but there is often resistance from the editors. Are there any case studies or publications discussing your results?

No case studies or papers, but the fees remain in place, and the market has adapted. Later, submissions became more typical, with more lower-quality ones coming in, as the market adapted, but surely the fee has kept this a trickle rather than a flood, especially as this particular journal has since become #1 in IF for its field (nothing to do with submission fees, by the way, as just good, traditional editorial and publishing strategies achieved that). I think the downside is exaggerated and the upside minimized by those considering submission fees.

It will be interesting to see how publishers and major funders work out both ideological and cost considerations on APCs. For instance, the American Chemical Society (ACS) seems to have one of the more enlightened incentive approaches for their family of journals with OA discounts both to society members and to authors publishing from subscribing institutions. Their strategy is thus to use APC discounts to encourage society membership and institutional subscriptions.

Funder strategies toward APCs seem a bit murkier. In a study of institutional spending on open access publication fees in Germany, Najko Jahn and Marko Tullney describe how the German Research Foundation (DFG) supports APC payments only if the journal is fully open access and if the price doesn’t exceed € 2,000. The policy against hybrids indicates to me that the funder’s priority is not just open access to their funded research, but reflects ideological pressure toward full open access publishing. The authors describe some journals with deeply discounted or very low APCs which suggests to me some sort of subsidy or perhaps sticking out-of-network authors with higher APCs.

According to Jahn and Tullney, “Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG), the largest German research funder, has strongly influenced how universities manage institutional support for these charges.… The DFG has enforced a set of criteria with which grantees [journals] have to comply and which has resulted in similar policies regarding support for publication fees across German universities. These criteria exclude the sponsorship of articles in hybrid journals and the funding of articles for which the publication fee exceeds € 2,000.”

I recall sitting at a table in a conference room with folks who were much older than me – some were real old like 40! – and the discussion devolved into the cost of page charges which were getting so high that authors were complaining. Now we charged a minimal subscription rate to basically cover postage and handling. All these price increases were happening because of costs going up. In fact, an editor in NYC could command $10K per year! The result of the conversation was a decision to increase the cost of the subscription and the page charges would not increase. A few years later it was decided to end page charges and just charge a subscription rate. By just charging a subscription rate one could get rid of all those book keepers and time and effort needed to follow the costs of production tied to the page charges.

Now if we substitute a submission charge for a low subscription charge it seems the same conversation is occurring all over again. I say this because at some point the submission charge will become a profit center.

It is interesting that when I put on my reader’s hat everything is too expensive to acquire and when I put on my author hat everything is too expensive to submit unless I have someone else pay for it.

STEM publishing is a monster that consumes money and spits out paper and the very small specific publics which consume the paper are engaged in an elusive quest for a free lunch….

I’m pleased to see the discussion about submission fees, because CDL has advocated this with publishers for many years as a means of cost control as well as a path toward OA sustainability. I think it’s also worth pointing out that cross-subsidization, which David discusses in the context of PLoS, is far from unknown in the subscription journals market.

I do want to correct one possible mis-impression about our Pay It Forward project though. David’s comment about hybrid APCs being artificially low, which immediately follows his reference to our study, presumably reflects his opinion – it is certainly not drawn from our report. Our analysis of publishing costs yielded a median of under $2,600 at the high end, with $1,100 as a reasonable baseline cost, including margin.

To clarify, the statement that APCs are artificially low is my own, not drawn from the Pay It Forward report.

I think it’s also worth pointing out that cross-subsidization, which David discusses in the context of PLoS, is far from unknown in the subscription journals market.

Sure, but no one is advocating for a flip of all journals to the subscription model and using those particular titles as viable examples.

Our analysis of publishing costs yielded a median of under $2,600 at the high end, with $1,100 as a reasonable baseline cost, including margin.

As was noted in your analysis, it became too difficult for you to encompass all of the costs involved in publishing a journal and instead the study focused on what you suggest “publishing a journal could cost” rather than “rather what publishing a journal typically does cost”. At that point you’re into the theoretical, and I have concerns that the figures suggested fall prey to the same errors Joe Esposito discussed here:

https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2016/09/07/how-much-does-publishing-cost/

David, our ‘high end’ median was derived from the literature review tranche of our research, which relied on studies such as those conducted by RIN/CEPA and others – so not theoretical at all. In fact none of our figures if I recall correctly were based on what publishing ‘could’ cost – that was an original aspiration, but it proved too elusive because of the variability you suggest – not just in terms of kinds of costs, but whose costs – in what geographic region, whether using new or legacy technology, etc. So we instead relied on formal and well-regarded studies, tax forms of non-profit publishers, and direct input from a few ‘new entrant’ publishers with lower cost structures.

Thanks Ivy, those quotes were from the introductory material to that section of the report, sorry if I’ve misinterpreted them. But the very public examples of eLife and the high end PLOS journals makes it clear that the range presented in the study is too narrow. The cost of rejection is difficult to quantify, as each published article must pay for the work done on each rejected article, and for quality journals, the rejections vastly outnumber the acceptances. What percentage goes through desk rejection and what percentage goes through full peer review (and how many rounds of peer review) before rejection is going to vary wildly between journals.

Also, because the study focused on STEM publishing, it doesn’t tell us much about the needs of Humanities and Social Sciences publishing. In these fields, the post-acceptance editorial work is tremendously different and much more intense than is often seen in STEM:

https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2015/03/25/guest-post-karin-wulf-on-open-access-and-historical-scholarship/

“[submission fees] seem an obvious and practical way to give the field what it wants (and clearly there remains significant demand for high-end, high-service, highly-selective journals) in a sustainable manner.”

Independent peer review services are an alternative to journal submission fees, and have the advantage of a much lower rejection rate (<10% at Axios). The service acts as a brokerage between authors and journals, steering papers towards journals that actually want them.

Authors are guaranteed that the journal will give serious consideration to their paper (viz. the 85% acceptance rate for papers reviewed by Axios), and because the dreck never arrives at the journal, they can continue to be highly selective while dealing with many fewer submissions.

It’s an interesting idea, but given that most journals are still going to run a round of peer review on any submissions, even if they’re improved, there will still be an expense. Since review services like Axios charge a fee, at best you may just be shifting costs from one company to another. It might actually add to costs for authors, as garbage papers are going to have to pay the full rate at Axios, while at a journal they’ll only incur a small desk-reject fee.

And of course there’s still the question of whether this is a business that is sustainable and can scale to a level to meet the full needs of the market (not sure what Axios would do with a paper on String Theory or the Gettysburg Address). I worry that it might just as likely result in added expense, delays in publication and more hoops for an author to jump through.

One number that’s surprised us is the proportion of papers that get accepted by the journal without further review – it’s over 50%, even for quite selective journals.

The acid test on whether submission fees or IPR would be more efficient depends on the total number of review rounds being performed.

With Axios, there’s one round with us, and about 60% of the time there’s a second round at the journal (i.e. 1.6 rounds). 15% of papers get rejected and some of those have 3+ rounds. Call it an average of 1.7.

With the current system, and ignoring desk rejects, papers get reviewed once at a particular journal, and about half get a second round of review, so that’s 1.5 rounds to start. Generously, half of those papers are rejected, so that’s another 0.75 that get reviewed (and re-reviewed) at another journal. A quarter get rejected twice, for an additional 0.37 rounds. The average for the current system is at least 2.6 rounds.

That IPR is more efficient makes intuitive sense – compared to the current system, authors are submitting to a journal that’s much more likely to accept their paper. For the current system to be better than IPR, the acceptance rate at most journals would need to be c. 80%.

I suspect a big issue would also be how well authors listen to you as far as deciding where to send their paper. If the pool was considerably widened, I’m willing to bet you’d get more of the sorts of authors who send their papers to wildly inappropriate journals, who might not be willing to accept your advice as to where their papers are actually likely to wind up.

QJE and JFE aren’t directly comparable – one is a top econ journal the other a top finance journal. Natural alternatives to the QJE would be one of the other top econ journals (JPE, AER, Econometrica, RESTUD). A better comparison for the JFE would be the other top finance journals – J of Finance and Rev Financial Stud.

Submission fees are common on finance journals – close to being the norm. I suspect JFE’s is at the high end. RFS charges $240 ($300 to non-members), and JoF charges $250 to authors from high-income countries. The JoF got 1110 new submissions in 2015 according to the 2015 editor’s report. The RFS got 1636 submissions in the last 12 months according to its website (not clear whether revised submissions are included in that). So on the face of it the higher JFE fee doesn’t seem to be a major factor for authors.