Editor’s Note: Today’s post is by Bob Nardini. Bob is Vice President, Library Services at ProQuest Books. In 1985, a few years out of library school at the University of Toronto, he began to work in academic bookselling and has been involved with library book collections ever since. Bob is based in ProQuest’s office in La Vergne, Tennessee, outside of Nashville. Part 2 of the post is available here.

An Enduring Debate

“Last month the library announced a startling change in plans for the acquisition of books,” reported Robert Zaretsky, professor of world cultures and literatures at the University of Houston, to readers of the Chronicle of Higher Education in May 2018. “Instead of ordering books by anticipating faculty and student needs,” he wrote, “the library will adopt an increasingly popular strategy known as ‘patron driven’ acquisition.’” This news, Zaretsky said, sent “a chill across campus.”

Actually, the chill didn’t reach across the entire Houston campus. What he meant were the university’s humanities departments, where for years as university administrators “relentlessly bled their libraries,” he and his colleagues from ever-chillier offices watched university money flow away from what he called “Humanitiestan” and toward “STEMistan.” He also noted that students, if visiting the library at all, were there usually just to check out a laptop or connect with other students. Zaretsky signed off more in resignation than protest. Libraries, he wrote, “cannot continue as they have.”

Probably, Zaretsky had no idea he’d touched questions first raised some fifty years ago. To say much has changed for academic libraries over that half-century goes beyond truism — including for most libraries, building book collections as their core mission. But one thing that hasn’t changed is the durability of debate over who should select the library’s books, an abiding question that over the decades periodically subsides, then rises again.

Books may be less central than in the past, but they are still an element in the periodic table of academia. Books carry more cultural weight than even the most highly-cited (or priced) journal. Universities continue to produce and consume books, and in great numbers. “Book knowledge” remains a mark of learning and status. On top of all this, books are an article of commerce, and the question of who controls a budget and how money changes hands is always good for keeping debate alive.

This debate began in the 1960s when universities enjoyed a surge in support. Academic departments held the book money and the library’s job was to spend it against orders sent over by the faculty. In effect, it was a “patron-driven” arrangement — at the time, an unknown term. But academic librarians, only then coming into their own as a profession, believed they could do a better job than professors, experts in their disciplines but untrained in the professional responsibility of book selection. Librarians pointed to “gaps” in the collection, as faculty book choices frequently ignored anything beyond their narrow interests. Balanced, thoughtful selection, by librarians, under principles of an emerging specialty, “collection development,” could put the right books onto the shelves.

Over time, librarians won the argument. They gained control over the money and, in a period when to provide books for the university community was the most important thing a library did, enjoyed the status of that role. But, soon it was all too apparent that libraries didn’t always have the staffing needed to select the books and spend so much money. The answer for some libraries was to start approval plans, an idea introduced by the Richard Abel Company of Portland, Oregon. Approval plans would efficiently spend down the budget and free librarians from routine selection duties. While some saw a godsend and were advocates from the start, others felt a line had been crossed. How could libraries turn a mark of professional responsibility into a commercial bargain? “A more casual attitude toward the expenditure of funds,” on the part of libraries, and a “greedy demand for the library dollar,” on the part of vendors, was how one librarian viewed the situation in 1969.

When the Abel company went under, in 1974, some librarians thought this would mean the end of approval plans. Instead, new companies were formed, and the debate continued. In a 1979 library school textbook, for example, students read of “various justifications for turning over the selection of what is needed by the university library to a businessman, whose primary interest in the academic community is profit.” In the end, philosophical argument mattered less, though, than the efficiencies approval plans offered, once 1960s growth gave way to stagnant budgets in the 1970s and pressure on staffing that, at many libraries, has never relented. “The primary reason” for approval plans, one librarian explained in an Association of Research Libraries survey in 1997, “has been the need to re-assign static staff resources to meet other priorities, e.g., user education and electronic initiatives.” The same ARL report also captured a more succinct, and by now seemingly timeless remark explaining efficiency measures of all kinds: “Using [approval plans] now as part of downsizing of Technical Services.”

A Perfect Storm?

If Robert Zaretsky was unaware he’d joined a discussion begun long before, it’s unlikely the students he cites — or even seasoned library users — give any more thought to how the books they might need got there than they do to how the library acquired its tables and chairs. Libraries come outfitted with books maybe? In fact, these unknowing patrons are at the center today of a renewed debate.

The notion that patrons might select books for the library, if in a context vastly different from the 1960s, was reborn in the early 2000s when adventurous librarians, thanks to the emergence of ebooks, gave the method a try. The new format removed from the buying equation all shipping back-and-forth of physical items. When MARC records for these ebooks were loaded into library catalogs, it was possible to charge libraries only for the ones patrons used.

These arrangements were all but universally considered “pilots” by the librarians launching them and this period of trial and error indeed produced enough error to reinforce the opinion of those inclined to be skeptical or cautious. Something of an urban legend arose from a Colorado library’s experience in acquiring more ebooks then they’d have wanted on the subject of bananas, the result of a class assignment on the economics of that fruit and the resulting student clicks on possibly relevant titles leading to these unwelcome purchases, each one caused by a patron.

The episode was retold in a 2009 Charleston Conference presentation by Claremont University librarians who accompanied the tale with a report on Claremont’s own experience with a patron-driven program, an experience far more positive and one presented with analytical rigor. Their data “clearly and repeatedly demonstrate” that a patron-driven model “builds collections of ebooks that are used more often and have a wider audience than their pre-selected counterparts…ownership of obscure unwanted books is NOT an inevitable outcome of use-based ebook selection.”

2009 was a year when librarians had reason beyond Claremont’s data to re-examine skepticism toward the patron-driven, or “demand-driven acquisition” model (DDA). “Perfect storm” would be too mild a phrase to describe the turbulence academic libraries experienced when financial catastrophe brought down Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers, came close to taking out the automobile and mortgage industries, and delivered the entire economy to near collapse. Universities lost significant portfolio holdings in the crash, and library budgets were widespread casualties in the wreckage.

As librarians became all too conversant with circulation and usage data that was dismal, data often confirming the once maligned but suddenly heavily cited Kent (or Pittsburgh) study from 1979, shelves of seldom (or never) used books followed bound journals out to the loading dock, the more fortunate titles destined for offsite storage, the rest for less desirable destinations; all making way for group study space, for teaching spaces, for writing and digitization labs, for cafes. Campus and then library administrators became interested in “return-on-investment,” once a new term for most librarians, although soon familiar to all.

Those who might have aimed for careers as expert subject specialists instead immersed themselves in outreach to the faculty, in advocacy for open access, in information literacy and bibliographic instruction efforts, in digital scholarship, in library publishing, in copyright expertise, and in other areas of academic library reinvention. Even those librarians who still identified as selectors, unless they worked at a large research library and often even then, found that newer duties left little time for book selection. Storms blow over, but for academic libraries, climate change would be the better analogy, as technological disruption combined with financial crisis, local budget and space pressures converged with larger upheaval, and the enterprise of higher education went lean and online in a thousand ways.

Buying books on the chance they might be needed, in the face of evidence many never would be, no matter if expertly-selected or cleverly-profiled; or bought because they might go out-of-print, a status less problematic and even irrelevant with the rise of Amazon and other companies who operated online, and new print-on-demand companies on the ground, became a practice hard to defend. Like the rise of approval plans a generation earlier, this was due less to librarians bowing to argument than to unanswerable economic reality and the imperatives of technological change.

After the Crash

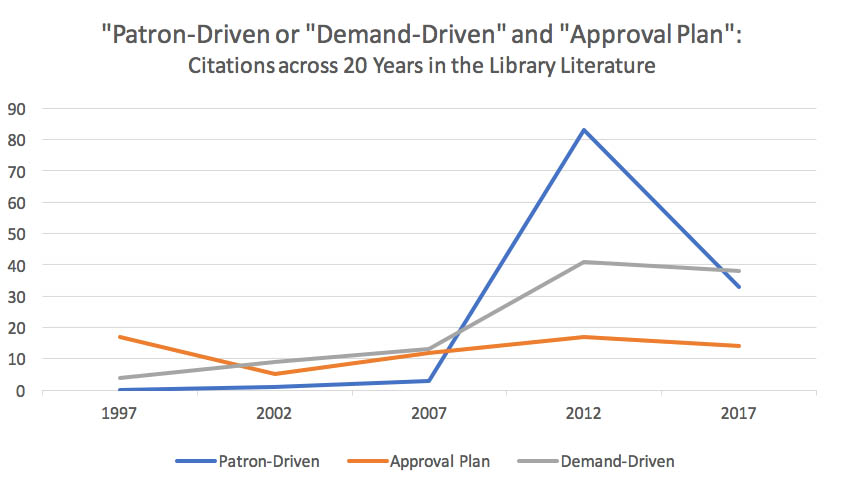

A twenty-year count of citations for the established search term “approval plan” and for the newer terms “patron-driven” and “demand-driven” shows that after the crash, early-adopting libraries were joined by others who needed to try something. At the same time, the graph shows how “patron” overtook “demand” in librarians’ choice of words, as they expressed to one another and to their administrators, where their efforts were focused after the crash.

The graph’s downward slope after 2012 results from librarians moving on to new interests in their research and writing, as so many had moved on in their work. Debate over book selection, years before, had been ignited and then doused by approval plans. The pattern repeated with DDA, as initial skepticism was overwhelmed by too many examples of the new practice working well enough at one library for the next to come on board.

Libraries had again found ways to adapt to severe pressures on their staffing, and after 2008, on their budgets; while this time also having to navigate a culture change demoting books if not to the status of curiosity like a card catalog or microfilm reader; nor to the state of ballast as befell many runs of bound journals; but to a station where routine selection was sometimes viewed as roughly on par in value with transactions at the circulation desk. Not that libraries, especially larger ones, walked entirely away from what some began to consider the legacy routines of approval plans and title selection. Instead, a rainbow of localized strategies appeared, combining established practices with new ones.

Part 2 of this post can be found here.

Discussion

2 Thoughts on "Guest Post — A Long Tale: Why Book Selection is Always Up for Debate, Part 1"

In 1958 the library was a place where guys went to meet girls and girls to meet guys. Only graduate students went to libraries to actually do some work and they were segregated in that they had study carrels. Thus, the library’s purpose met reality on the library’s steps where one tried to get a goodnight kiss before curfew. The librarian came into play only when one actually had to accomplish an assignment and s/he would direct you to either the dreaded card catalogue or that big set of books – the serial catalogue – that guided one through journals. At least that’s the way it was 60 years ago at the University of Florida!

Well, the curfew’s gone and the dynamics are different now, but that girls-guys function of the library is having something of a revival today. The librarians are busier, though. Thanks for commenting.