Editor’s Note: Today’s post is by Tao Tao, an independent consultant focusing on the Chinese academic market. She has worked in the scholarly publishing industry for 24 years, starting as an assistant editor of Chinese Medical Journal, the oldest medical periodical in China. Later she joined The Charlesworth Group, a UK publishing services company, and helped establish their first overseas office in Beijing. Fifteen years as the General Manager of Charlesworth China and four years as Vice President China Sales Charlesworth USA have given Tao a good understanding of both sides of the Chinese academic market.

No one says selling into the Chinese market is simple, but is it unmanageable, given that there are nearly 1.4 billion people speaking a very different language and sharing a very different culture? The answer is: not necessarily, if you know the basics, and then zoom in on the details.

As in any other country, the academic market in China consists of universities and research institutes, and hospitals for medical content.

Universities

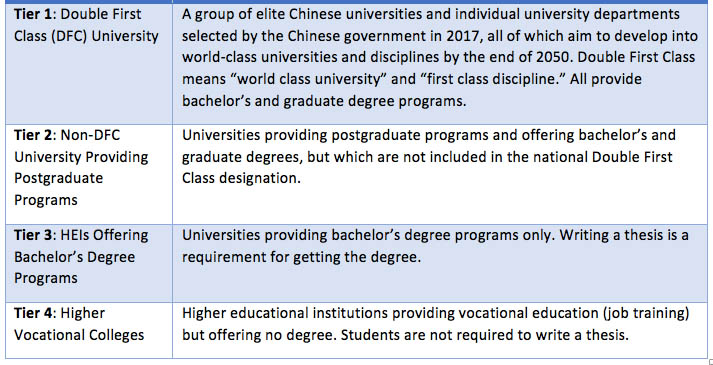

Universities are the largest portion of the pie. According to the Ministry of Education (MOE), by May 2017, there were 2,631 regular higher educational institutions (HEIs) in mainland China. The MOE list does not include 3 military universities. For completeness, the rest of the article includes these 3 universities. These HEIs can be divided into four tiers. Differences between tiers are shown in the table and Chart 1 below.

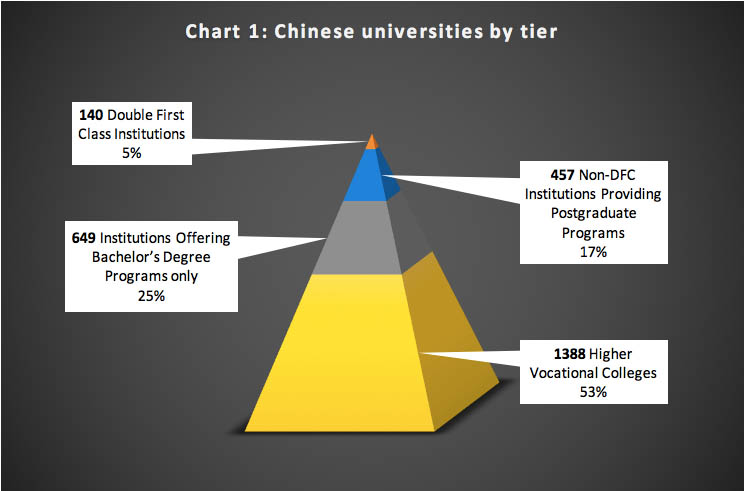

Is each of these 2600+ institutions a potential customer of international scholarly publications? Theoretically, yes. But in reality, research activities concentrate in the top two tiers, which not only attract the top students, but also absorb most government funding. International scholarly publishers should find the majority of their Chinese audience in the 597 Tier 1 and Tier 2 universities. Below is an example of some top science titles, showing distribution of their Chinese university subscribers in different tiers:

No doubt Tier 1 yields the highest return on investment and is worth the best sales and marketing effort; but Tier 2 should not be ignored: here there are many ambitious universities that get financial and administrative support from their equally ambitious local governments. Some provinces have started to form their own DFC school list. Recently Hunan Province announced its initial DFC list which includes all 19 Tier 1 and 2 schools in its territory. Tier 3 is worth keeping an eye on if you have enough marketing budget.

Geographically, there are altogether 143 schools in Tiers 1 and 2 (24% of total) in the vast West area (12 provinces), and 454 (76% of total) in the rest of China, due to the imbalance in population and economic growth. The brown area in the map below shows the West Provinces.

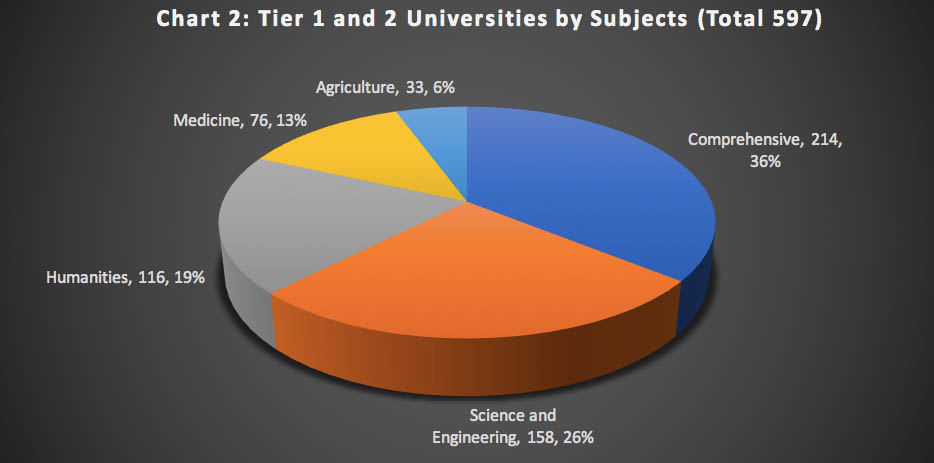

Many scholarly publishers do not need to deal with ALL Tier 1 and 2 schools. For example, the 116 institutions in Tier 1 and 2 that teach and research humanities subjects only (Chart 2), such as art, management and law, are not potential customers of a medical publisher. But for most comprehensive universities, a deeper look is needed to find out which subjects are taught and researched on the campus. The best disciplines in a school are indicated by whether they are included in the DFC plan, and/or which State Labs and postdoctoral sites are located in the campus. The final short list of potential university subscribers for any STM publisher may not exceed 400, a much more manageable number. For example, Nature has 177 university subscribers through the Chinese university consortia organization DRAA (Digital Resource Acquisition Alliance of Chinese Academic Libraries), after 16 years of consortia selling into the China market. Elsevier’s ScienceDirect (over 2000 titles covering 24 subjects) has 338 university subscribers through DRAA after more than 17 years selling into China (data from http://www.libconsortia.edu.cn).

Research Institutes

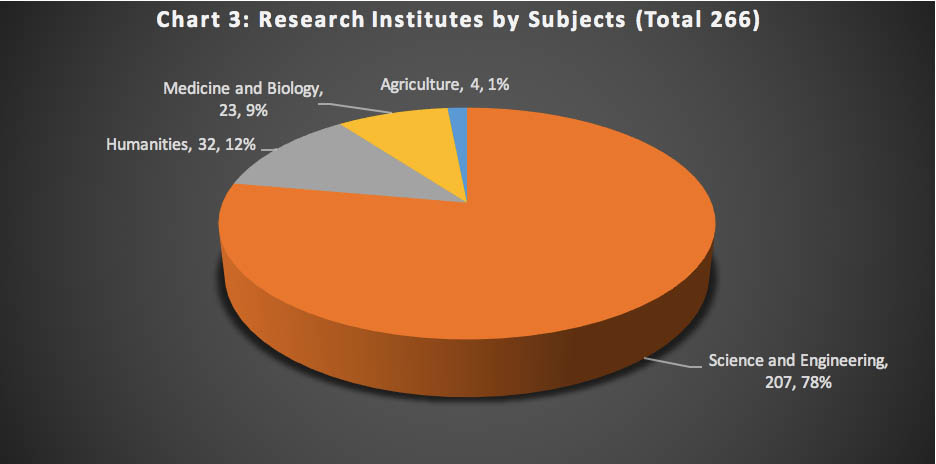

There is another, smaller segment of the China academic market as well. According to the 2017 Educational Statistics published by the MOE, by May 2017 there were 237 research institutes providing postgraduate programs. The MOE’s Higher Education Student Information and Career Center, however, lists a total of 266 research institutes that are recruiting postgraduate students. It is unclear how many research institutes there are that do not serve a direct educational purpose.

The most prestigious research institute is the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), consisting of 128 sub-institutes/research centers located all over the country. The other major national research institutes are the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (CAMS), Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS), and Chinese Academy of Agricultural Science (CAAS). CAS, CAMS, and CASS each have a university, too, and these universities are included in the MOE university list.

Using the same definition as that of the universities, all research institutes are in Tier 1 and 2 (the universities of CAS and CAMS are in Tier 1). With a few exceptions, the 266 research institutes share these features:

- Highly specialized in research subjects that are usually reflected by the institute’s name—for example, Zhengzhou Tobacco Research Institute

- Providing postgraduate programs only

- Number of students is small, in some cases fewer than 10

- Belongs to a central government department or a state-owned corporation

- Does not have a library

Due to these features, despite the total number, the research institute market is much smaller than the universities, and it is easy to identify potential buyers from the institute names.

Hospitals

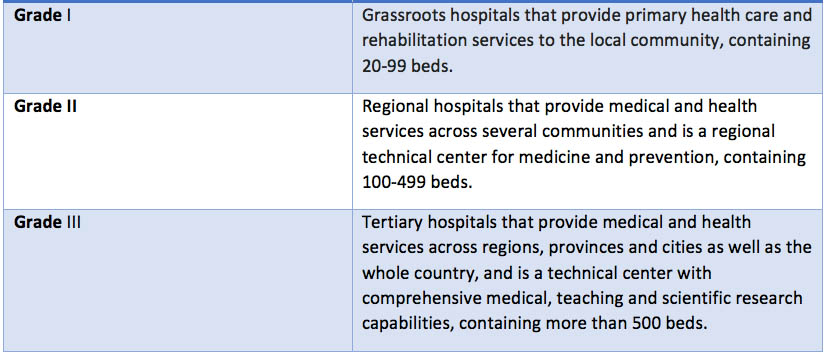

According to the National Health Committee’s 2017 Statistical Bulletin, by the end of 2017 there were 31,056 hospitals in China, more than half of which were private. The hospitals are divided into 3 grades.

Each grade is further divided into 3 levels (Levels A, B and C), according to the hospital’s ability to provide medical care and education, and conduct medical research, with Level A being the highest. The top hospitals are labelled Grade III Level A, or 3A. Aside from the size and other indicators, 3A hospitals differ from other hospitals by providing more advanced education and science research. Although all hospitals need medical literature, English content is mostly read in 3A hospitals only. The needs of other hospitals are satisfied by the 1196 medical journals (1071 in Chinese language) published by Chinese organizations, including Chinese editions of some top international medical titles such as BMJ and The Lancet, as well as translated articles published by international publishers in various formats. As of 2017, the number of 3A hospitals was 1360. Many 3A hospitals are affiliated with a medical college or a research institute. In some cases, a hospital and the university or research institute are the same entity. For example, when you hear people talking about the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (CAMS), Peking Union Medical College (PUMC), or Peking Union Hospital, they are talking about the same organization. An affiliated hospital can often get access to international publications through the mother organization.

Summary

In summary, for any international scholarly publisher, the market demand and buying power can be found mostly in the top 20% of universities and a few research institutes. With further research, a carefully targeted list can be produced to enable precise and effective sales efforts.

Discussion

18 Thoughts on "Guest Post — The Academic Market in China: An Overview"

Thank you for the informative post. Do you have insight in how China will react to Plan-S? If publishers become OA is China prepared for funding the increase in author fees? Do you know the best way to start the conversation with China about this?

The largest science library – National Science Library – has always been actively involved in and supporting OA publishing. It is also the leader in this movement and where you may want to start a conversation. This article is a good summary of where China stands with OA: https://openscience.com/china-mandates-open-access-promotes-institutional-repositories-and-demonstrates-commitment-to-open-science/.

Thank you for mentioning the post. In this context, I wonder if there have been any further developments in relation to Open Access in China and Asian more broadly more recently. The Plan S has been receiving a lot of attention internationally, even though this initiative continues to evolve: https://openscience.com/in-response-to-criticism-the-plan-s-adopts-a-flexible-stance-toward-paywall-based-journals-and-hybrid-open-access/.

There were discussions and sharing of the news on Plan S right after it was signed, in the science publishing community in China. The tone set by the main media is “Open Access is world trend and answer to the requirement of modern science research”. It mentioned that many Chinese language journals already make their content OA on-line. There is also a lot of interest in starting new OA journals. I talked to three different organizations in the past 3 months, all of them confident in the success of their OA initiatives.

The progress of OA in China is indeed impressive. I assume there is more coverage of this topic in Chinese-language media.

Hi Nancy, the recent post in Nature news (https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-018-07659-5) and the position papers it mentioned (https://www.nature.com/magazine-assets/d41586-018-07659-5/nSTL-MOST-position-on-OA2020-and-Plan-S) seem to have answered all your questions?

A very useful overview. Are you aware of any analysis of the costs a publisher/platform can expect to incur to comply with China’s regulations re suppressing content? E.g., related to Taiwan?

That’s a tough question. I’ve not read any analysis on this yet. It is rare to find politically sensitive content in a natural science publication, and in social science, a lot are still read in print, where the import agents will do the job.

Springer is apparently suppressing about 1% of its content in China … https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/01/world/asia/china-springer-nature-censorship.html

Thanks Lisa. The news you shared says Springer “removed articles from its mainland site”. I think this is pretty easy to do without much cost. Its Chinese mainland site isn’t its main publishing platform. But when it says “1 percent of its content was inaccessible in mainland China”, it could be certain journals or books in the Springer package are not accessible in China , which is also relatively easy to do. The challenge would be to block 1 single article to Chinese audience only, without removing that article from the platform. I don’t know if any publisher has had such experience, and expect that to be costly.

The costs I mentioned above is only the direct cost, not indirect cost caused by damage to the publisher’s reputation, for example.

If you read around on this topic – with respect to Springer and to other publishers, you’ll find reports that this suppression occurs at both journal title and individual article level. But, I’ll admit, the reason I asked is that I have yet to see an actual analysis of this topic in any way that let’s us truly understand what is demanded and what is required to comply and this seems important for understanding doing business in China as a publisher.

You are right, that there is little information on what is a publisher demanded of doing, even vague in a license agreement. It is left to the import agents who is responsible for content review to resolve with the publisher. On-line content review was mandated more recently. Detailed provisions were published in January 2017 and effective from March 1 2017. It will be useful if some publishers/platforms can share their experience.

Thanks Tao, excellent post … on your point about the research centers not having a library, I assume you mean a physical library, CAS has a fairly comprehensive digital library that’s accessible to all their branches and researchers, right ?

I also find it interesting that the hospital grading system, is the opposite of the Higher Ed ones, Tier 1 = Grade III A

I’m sure there’s a lot more interesting and updating information about China too, including author/researcher data, perhaps a part 2 post ? … and it would be interesting too to have more country level updates from other contributors/geographic regions. Thanks for taking the time to write this for the Kitchen.

In fact, CAS is so important it deserves a whole separate chapter. It’s kind of unfair to list CAS with other research institutes, because it is probably larger than all the others added together.

Thanks Adrian. I wrote that “with a few exceptions” research institutes don’t have a library, and CAS is one of the exceptions. The library of CAS is also called National Science Library, it is physical sitting on a huge site (you’ve been there many times yourself). And you are right that it serves a big network of sub-institutions, both print and on-line.

I know the hospital grading system sounds odd, but it is official naming and I can’t change it. In Chinese, Jia, Yi, Bing are used which mean first, second and third respectively, and the best equivalent English are A, B, C.

I’m not sure it’s easy to get public data on authors. But in the scholarly publishing world, readers are also authors, so where the research is, where the researchers are. Knowing where your audience are can help you find your authors, too.

China has a very large academic market and potential for scientific publications. However, I think concentrating on few institutions may not yield the result for both publishing houses and universities. Universities small or big require their share of publications. OA proved to successful though there must be quality control over some journals.

Bashar H. Malkawi

Thanks Bashar. This article focuses on sales potential only. The potential for authorship and readership would be a different story. The latest data (of 2016) show only 256 Chinese universities have an R&D fund of more than 0.1 billion RMB, which is about 14.5 million USD. For many small institutions, it would be many years before they could afford the international publications they want. This is one of the reasons China is enthusiastic about Open Access and welcomes Plan S wholeheartedly.