Editor’s Note: Today’s post is by Rachel Maund, Director of UK-based Marketability (UK) Ltd, an international publishing consultancy specializing in marketing and training. She works with many of the UK’s academic and specialist publishers and training providers, and regularly conducts training workshops and programs overseas, including in Singapore, China, Mexico, Australia, the US, and Europe. Some of the content in this article started life in accounts of working in Mexico which have appeared in The Marketability eBulletin.

Take an internal flight in Mexico and there’s a good chance that all the arm-rests will be up. Mexican publishers I’ve worked with have been universally warm and open, and I’m sure there’s a connection between this and a wider national trait of not feeling the need to demarcate personal space.

Working with the publishing community here is a refreshing experience. The region brings with it enormous challenges, yet there is an undimmed passion for publishing great content really well, and in bringing new authors to market. To this end they are often enterprising at solving problems. Take, for example, the author of a color-illustrated book who got carried away and submitted far too many illustrations to their tiny trade publisher to make it viable. The publisher retained all images in outline and it became a coloring book instead.

Unfortunately, a weak supply chain creates a bottleneck where there is frustratingly limited consumer access to this excellent publishing.

Mexico’s logistical challenges, from government interventions in publishing to Amazon.mx

Between 1990 and 2000, Mexico’s literacy rates for 10-15 year olds went from around 12% to over 90%, creating a new generation of wealthier, literate, and digital-savvy readers. This was achieved in part by the government providing free books directly to schools. But bypassing local publishers and bookstores led to tougher trading conditions for them, as well as fostering a culture in many that books ‘should be free’. Among that wealthier younger generation, though, there is also genuine hunger for books in a country where 94% of municipalities have no sales outlets for them. Gandhi is the largest bookstore chain with 41 stores, but no fewer than 18 of these are in Mexico City. Independent bookstores are few and far between.

Mexican publishers are used to playing second fiddle to international giants. 80% of trade sales come from either Spanish publisher Planeta or Random House. The impact on publishers of government intervention (those free school resources) has been further compounded by international textbook publishers Santillana, McGraw-Hill, Pearson, and others doing lucrative deals with the state, effectively shutting out local competition.

Reliable market data is hard to find too, making the market and competitor analysis that we take for granted to inform publishing decisions and benchmark performance a significant challenge. It’s telling that when I was recently researching the Mexican market (to supplement what I learned from friends there), there was a real paucity of reports, among the most recent being From the Ground Up: Inventing Mexican Publishing (Elisabeth Watson back in 2013).

Mexico is still largely a cash economy and the combination of an expensive postal service, a weak supply chain (scarcity of specialized book distributors and wholesalers), and relatively low usage of credit/debit cards has meant that the appetite for books has not easily been met by online retailers either. However Amazon moved into the market in 2015, opened a mega-warehouse near the capital in 2017, and launched Amazon Prime in March of that year. They promise delivery in 1-2 days, at least in Mexico City – enough to impress customers unused to such speeds. For Amazon, the potential of financial services in this market is very appealing: Amazon Cash and its debit cards enable customers to deposit funds to their account at convenience chains such as 7-Eleven. By March 2019, Amazon was working on a mobile payment system in partnership with Mexico’s central bank, with CoDi, enabling payment through QR codes. Although gathering momentum, the sticking point here is that banks are not universally trusted. No potential solution in Mexico is ever as straightforward as it should be.

Amazon has other challenges of its own. In November the former head of Amazon.mx fled the country suspected of the murder of his estranged wife by a hitman in Mexico City. Last heard of in San Diego, he remains at large.

Ultimately, whether Amazon succeeds or fails in Mexico, it will have raised the bar in terms of consumer expectations – and, just perhaps, publishers may benefit.

Open access in Mexico and Latin America

Latin America is way ahead of anywhere else when it comes to publishing open access (OA), embracing it from the start for both journals and books.

Unlike their US and European counterparts, publishers didn’t have a sustainable commercial model to protect. Academics in the region are committed to OA as they not only believe that research should be freely available, but crucially that this is how to get recognition internationally. Distribution of content is managed by the scholarly community, with their own well-established (over two decades or more) journal platforms and repositories, and supported by public funds as part of the public infrastructure needed for research.

APCs are not a feature of the Latin American OA model. They’re considered to be unrealistic in the region and potentially to threaten research integrity by continuing to favor rich institutions. And this definitely means that academic authors see their publishers as allies, without the tensions or hostility that we continue to see between the two communities elsewhere. Digital subject repositories have been developed in Mexico since the 1990s, with the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) playing a leading role in developing visibility for OA journals.

The Guadalajara Book Fair (FIL)

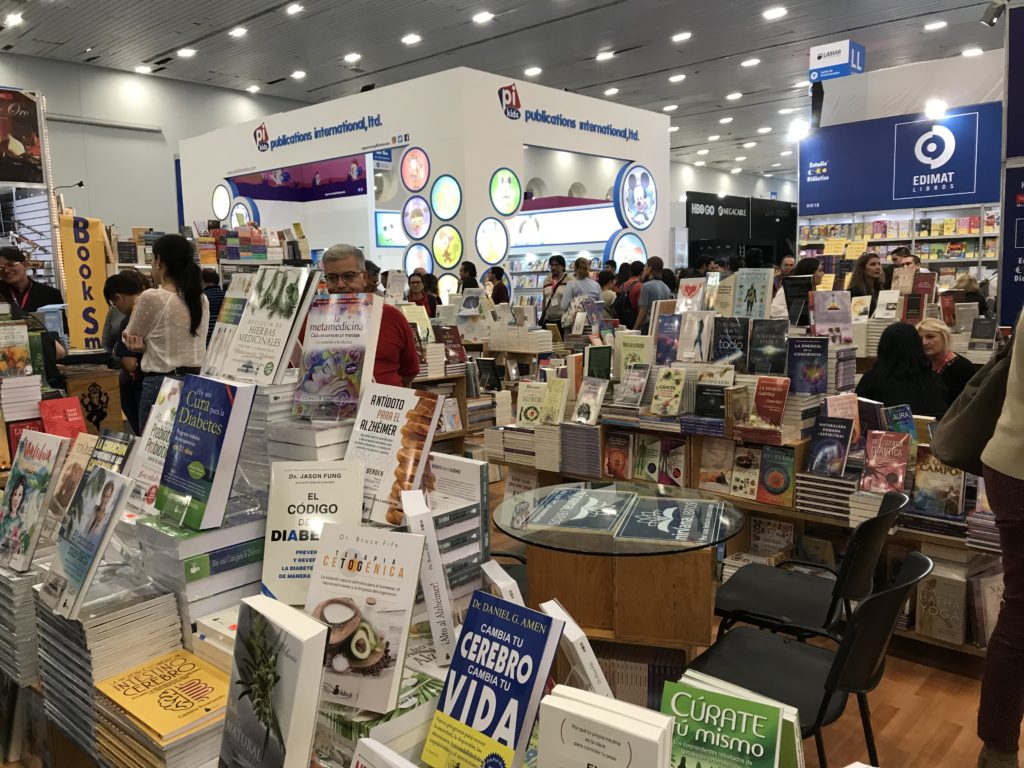

This book fair is the most important in Ibero-America, a truly buzzing cultural event which takes place over 9 days. Nine days!

Created 33 years ago by the University of Guadalajara, two things set it apart from most Book Fairs. The first is that it’s pitched equally at the book trade and at the public. It’s also always had a very strong focus on academic and specialist publishing, with a lively program of dedicated events and seminars.

Last December’s FIL attracted some 840,000 members of the public as well as 20,000 books professionals and 2,280 publishing houses from 47 countries. The air was crackling with the excitement of the public visitors with such wealth laid out before them – stands heaving with books, authors delivering talks, and panels debating, with music drifting across from other stands. Bookseller business was brisk. Interviews were happening everywhere in corridors and quiet spaces, for local and regional radio stations. FIL is open to the general public from 4pm every day, all day Thursday, and until 11pm on the closing Friday. 11pm!

Would that other book fairs could be this much fun, or so relevant to the local community.

And what’s the future of publishing in Mexico?

I’ve been working with Mexican publishers for 14 years, and although the challenges are very real, I’m optimistic for them. The combination of passion, resilience, and enterprise is a match for those logistical issues, and perhaps even for Amazon. The country is embracing digital, there is a hunger for books (digital and print) only partially being met across this huge country at present, and as new payment methods become established, they have the potential to unleash a lot of business.

It’s telling, I think, that when I was developing marketing workshops for university press publishers at FIL, I was told that they were doing ‘little or no marketing’. I think that’s their perception because they don’t have processes in place – but because they rely on doing what seems sensible at the time, those processes don’t weigh them down either.

‘A new reading culture depends on the publishing industry itself to use campaigns, affordable pricing, and activities that complement governmental programs’, commented Felipe Rosete, Editor at Sexto Piso. This is a publishing community committed to rising to its challenges and to embracing change.

Mexico also has a very proactive publishing association in CANIEM, the aims of which include tackling three of the industry’s biggest issues: academic and specialist training to help companies expand into overseas Spanish-speaking countries, data management, and the development of a specialist resource center at CANIEM’s Center for Innovation in Mexico City.

Sources include:

- Carlos Anaya Rosique and Jesus Anaya Rosique, both of CANIEM (the National Chamber of the Mexican Publishing Industry), www.caniem.org.

- From the Ground Up: Inventing Mexican Publishing, Elisabeth Watson, 2013, on www.publishingtrends.com. International Science Council: Plan S and Open Access in Latin America: Interview with Dominique Babini, 2019 https://council.science/current/blog/plan-s-and-open-access-interview-with-dominique-babini/

Discussion

2 Thoughts on "Guest Post — Mexican Publishers Face Significant Challenges, but They’re Uniquely Equipped to Meet Them"

Interesting article. How does the OA model in Mexico work without APCs?

The drivers of OA are different in Latin America, where the print and subscription models have never really been viable, and where visibility of published research was poor. The region embraced OA early seeing it as an opportunity to increase visibility, establishing networks of repositories decades ago. With commitment to making publicly funded research freely available, APCs weren’t considered a viable economic option either. Funding is therefore dependent on government, agencies, and international bodies, all operating to raise the profile of excellent research from the region. Publishers continue to add value in ensuring quality and visibility of the published research, this being a requirement of the repositories. Whether this model is sustainable long-term is an interesting question, but in the meantime Latin American publishers have no fear of Plan S. More information in this UNESCO report: http://www.unesco.org/new/en/communication-and-information/portals-and-platforms/goap/access-by-region/latin-america-and-the-caribbean/