Today’s post is the first of two in which we look at the state of persistent identifiers and what they mean for publishers—to coincide with the first meeting, on June 21, of the new UK Research Identifier National Coordinating Council (RINCC) and publication the same day of a Cost Benefit Analysis Report, funded by the UK Persistent Identifiers (PIDs) for Open Access project.

Over the last few years, there has been significant progress in developing recommendations, policies, and procedures for creating, promoting, and using persistent identifiers (PIDs). PIDapalooza, the flagship conference for PID providers and users, is now five years old and continues to grow. A number of funders and national research organizations are developing their own PID roadmaps, like this one from the Dutch Research Council (NWO) and the UK National PID Consortium. And the more established PID providers (Crossref, ORCID, DataCite), are being joined by new and emerging organizations and initiatives. These include the increasingly widely adopted Research Organization Registry (ROR), a community-led open identifier for research institutions; and the Research Activity Identifier (RAiD), an early-stage project, led by the Australian Research Data Commons (ARDC) and the National Collaborative Research Infrastructure Strategy (NCRIS) that is a container ID for research projects. In addition, Crossref themselves are working with funders to register DOIs for awarded grants.

Publishers — and publishing system providers — were early and enthusiastic adopters of persistent identifiers. Crossref was originally founded by a group of competing publishers to address citation linking in online publications, and the vast majority of their current 14,000 or so members are publishing organizations. ORCID’s founders also included several publishers and, while only 83 of the currently more than 1,100 members are publishers, you could argue that they punch above their weight, since ORCID iDs are used more often in journal publishing workflows than any other. Most major manuscript submission systems have ORCID integrations, and upwards of 2,000 journals now require ORCID IDs for the contributing author, with thousands more requesting them.

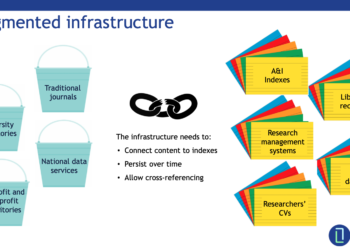

Nevertheless, we think it’s fair to say that many — probably most — publishers aren’t realizing the full potential of PIDs. DOIs are being registered for most publications (especially Crossref DOIs) and ORCID iDs are being collected, but their full value — for authors and publishers alike — isn’t currently being exploited. For example, despite collecting ORCID IDs for large numbers of authors (and, in some cases, reviewers too), manuscript submission systems typically don’t pull in much — if any — data from the ORCID record. This means that authors have to re-key information, for example, about their institution, grant(s), etc, which takes time and risks creating errors — to say nothing of the poor user experience when this happens across multiple journals, even when the author has signed in to the system using their ORCID ID. Publishers have also been less involved in the development of other PIDs and (likely related!) appear to be using them less than organizations in other sectors of the research community. For example, just six of the 60+ ROR community advisors are publishers.

However, the use of PIDs in open access publishing does appear to be of interest to publishers, and open access (OA) publishers are also more likely to have a clear PID strategy (F1000 and Hindawi are good examples). This may be because functionally, attaching accurate grant information to open access articles is critical for accurate billing and (where applicable) for demonstrating compliance with transformative publishing agreements. We’d like to see all publishers embrace the use of PIDs — above and beyond simply collecting ORCID IDs and registering DOIs for publications — to help improve the user experience for their authors and reviewers, and enable accurate recognition for their contributions; to increase discoverability and, therefore, use of their publications; to ensure compliance with an increasing number of policies, including Plan S; and to facilitate better analysis and reporting.

PIDs are much more important than they might sound

At PIDapalooza 2021, Ed Pentz and Rachael Lammey of Crossref gave a cheekily-titled talk “PIDapap-party-pooper: PIDs are a dead end; long live open infrastructure”. The talk itself is quite technical in places, so if walk-throughs of JSON-encoded API responses aren’t necessarily your bag, allow us to summarize what we think is the important point…

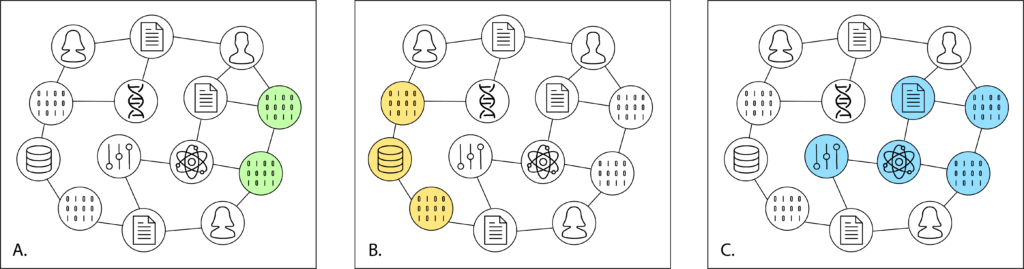

The most important thing about PIDs isn’t that they’re unique, or that they’re persistent or that they resolve, i.e., they prevent link rot. The most important thing about PIDs is the metadata that is associated with them — that is, the information that can be retrieved when a piece of software, platform, or web application requests data from the PID provider’s API, which can, and often does, contain other PIDs. Metadata enables connections to be made between published articles, researchers, datasets, computer programs, institutions, grants, funders, and more, eventually including things like shared facilities (EG CERN), instruments (the Hubble, or the 10.5T human MRI at University of Minnesota), and other strategic-level investments of national and global importance.

A blog post by Martin Fenner and Amir Aryani on the FREYA website introduces the concept of the PID graph and explains its importance. As more and more objects (publications, data, people, places, things etc) have richer and richer metadata associated with them, we can make more and more connections between those objects, enabling us to ask and answer useful questions, like how many research articles were written based on data from a shared instrument or which institutions or countries are producing the most impactful work in a particular area? This, in turn, enables us to analyze more complete, more timely, and more accurate data, leading to improved decision-making.

Given the fact that about $1.7 trillion is spent on research and development globally every year, you can bet that policy-makers in government, non-profit, and commercial sectors all want access to analyses that demonstrate whether or not they are making the best use possible of all that money.

Shifting policy landscape?

PIDs are here to stay because they offer policy-makers a transparent mechanism for tracking the impact of the strategic decisions they make, but how will this affect the publishing industry?

There is increasing demand for better quality research assessment, as shown by exercises like the UK’s Research Excellence Framework (REF), and Excellence in Research for Australia (ERA), as well as the San Francisco Declaration on Research Assessment (DORA). To date, the burden of enabling these assessments has fallen disproportionately on institutions, and the researchers and administrators who work for them. A 2018 Survey of Young Academy of Europe members found that early career researchers spend almost 20% of their time doing administrative work. This problem has not gone unnoticed. In the UK, for example, reduction of administrative burden for researchers has become a major policy objective. Funders are also increasingly taking concrete action. Examples of funder automation projects include the Europe PMC Grant Finder which links over 16,000 grants with DOIs to associated research articles; and the ORCID ORBIT project, created to engage funders in the use of persistent identifiers to automate and streamline the flow of research information between systems. And, in a recent UK government policy paper, national funder UKRI committed to,“stopping multiple asks for data or information that already exists elsewhere e.g. in ORCID, CrossRef, DataCite…”

With governments, funders, and institutions all working towards PID-optimized open infrastructure to reduce burden on researchers and increase transparency, publishers must be prepared to follow.

Potential benefits for publishers—automation and discoverability

PID policies aren’t just about shifting the burden of responsibility for administration away from researchers and towards funders and publishers. Well-designed open infrastructure offers benefits to all stakeholders through efficiencies as well as more complete, accurate and timely data. These benefits fall into three broad categories:

- Metadata exchange

- Automation of processes

- Improved business insight and analysis

Starting at the top, let’s consider how publishers currently obtain metadata. Typically, it’s gathered directly from authors, often at the point of content submission‚ and often via tortuous and lengthy systems that require authors to dig out grant numbers, affiliation addresses, collaborators’ ORCID IDs, and more. According to this recently published study (disclosure — Alice is one of the authors), most of the publisher respondents to a Metadata 2020 survey reported that their metadata is, at least partially, manually keyed — or more accurately, re-keyed. There are tools that can extract metadata from manuscripts but the results are usually mixed and require checking. If data can be positively identified and moved from one system to another, it will be more accurate and complete — while less of a burden, not only to authors but also to editorial and production departments. In addition, that metadata will be available for the author, the publisher, and the other organizations and systems they interact with, enabling everyone to benefit from a flow of high-quality information. As the Metadata 2020 study notes, “Through their interactions with researchers as both creators and consumers of content, publishers are well placed to play a stronger role in improving metadata workflows than they appear to do currently…”

Next up, automation, which extends the benefits of data exchange to keep data up to date seamlessly — and potentially even correct it automatically. ORCID auto-update, by both Crossref and DataCite, is a great example of this. It’s been around for over five years now, enabling researchers to have their publications automatically added to their ORCID record when the DOI is registered. Not only does this save them time, it also helps them keep track of their publications, and to cite and share them in grant proposals, as well as in research evaluation.

This information doesn’t just flow from publisher systems; it can flow into them too, enabling the last of our three benefits — better (and easier) business insights. For years, larger publishers have conducted their own analyses into emerging disciplines and markets using advanced bibliometrics and scientometrics techniques, with consultants typically providing the same sort of support to smaller organizations. In a fully PID-optimized world, more complete, more accurate, and more timely metadata,generated at source rather than mined or harvested—will make this sort of analysis more readily accessible to all, as well as more powerful.

In part 2 of this series, Alice and Phill will take a deep dive into the implications of the cost-benefit analysis itself and discuss the benefits that a fully PID-optimized research ecosystem would bring.

Discussion

8 Thoughts on "Why Publishers Should Care About Persistent Identifiers"

Congratulations Phill and Alice on what is a very useful post. I really look forward to the second one.

Anthony

Very nice post – PIDs are very important for the many reasons outlined here!

One PID (and subsequent one reason) that is missing (but very hopeful it will be taken into account in the next blog), are those for resources. Currently, 50% of the US annual preclinical research spend (56B $) is irreproducible, which causes delays in drug development, increased demands on resources, and drives up research costs unnecessarily (see https://journals.plos.org/plosbiology/article?id=10.1371/journal.pbio.1002165).

Using PIDs for resources such as biological reagents and reference materials would decrease this by 30% and these PIDs already exist; they’re called Research Resource Identifiers (RRIDs, see the newly founded non-profit RRIDs.org). RRIDs have been used by quite some authors and are mandated by a few journals (309,655 RRIDs used in 32,462 papers from >1,300 journals) but a broader update would give this a real (valuable) boost!

Hi Martijn,

Thanks for that comment. You’re right, of course. There are many other potentially very useful PIDs out there that offer potential solutions to a wide range of problems.

Another one that I think is important is PIDs for instruments. Similarly to RRIDs, instrument PIDs could play a significant role in helping improve rigour in communicating methods. They could also enable researchers to find appropriate collaborators with the right equipment for their needs, as well as help funders better measure the return on investment for large and shared equipment grants, which is an area of strong interest for many funders. Research Data Alliance have done work in this area through the PIDINST working group. (https://arxiv.org/abs/2003.12958)

On the other hand, for each new PID implementation, there’s a lot of work that needs to be done. If PIDs are going to deliver their full potential, they need to be properly integrated into funder, publisher, institution, and researcher systems and workflows. In a previous study that was commission by Jisc and ARMA, it was calculated that an ORCID integration cost 290 staff hours at a typical UK institution. (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1445290)

That’s part of the motivation behind the UK PID consortium, the RINCC committee, and the selection of five priority PIDs.

– ORCID for people

– DOIs for outputs

– DOIs for grants

– ROR for institutions

– RAiD for projects

By offering support to all stakeholders in the scholarly communications community, we can build sector-wide understanding and capability, starting with the five priority PIDs that will give us the greatest return on investment. Over time, as the value of the first five are realised, I hope we can create consensus around and drive adoption of more PIDs that will create even greater efficiency, transparency and discovery.

The statement that “The most important thing about PIDs is the metadata that is associated with them” is right on – thanks for being so clear. Two things I am curious about:

1) You mention that publishers require ORCIDs from only corresponding authors. This results in the vast majority of authors not getting connected to papers they co-author. Why do researchers put up with this? Where is the uproar?

2) Anyone that has tried to search ORCID for ids knows that a significant number, maybe even most, people in ORCID do not make their ORCID metadata available to the public. Of course this defeats the entire purpose…

ORCIDs will be even more useful when these two challenges are overcome.

To your first point, no one stops all authors on the paper from including their ORCID IDs, but where journals require them, usually only the corresponding author is required to supply one. This is largely the case because many (most?) authors do not have an ORCID ID so having all authors on the paper get one adds friction to the process. Also worth considering that the process of verifying an existing ORCID ID for a paper submission adds several steps to an already arduous submission process, so doing so on a paper with hundreds of authors for example, would be a lengthy and tedious task, requiring all of those authors to respond to confirmatory emails in a timely manner.

Thanks for pointing out that no one stops authors from submitting ORCIDs. Of course, I agree. I hope these blogs help researchers understand the benefits and hopefully make sure their ORCIDs get into all papers they author, co-author or contribute to in some other way and that their ORCID metadata are open.

You also mentioned friction in the process. In a blog post about Minimum Metadata (https://metadatagamechangers.com/blog/2020/12/23/minimum-metadata) I mentioned the idea of Conservation of Burden. I think it applies here as well: “It is important to keep in mind that the burden associated with reuse is conserved so, work that is not done by the data provider [researcher or publisher] inevitably falls on every single potential data re-user. There is no free lunch, so “minimum metadata” on the provider side means maximum work on the re-use side.”

Although a large number of authors do have an ORCID ID (there are close to 12M registered now!), the process for adding them, especially for co-authors, is far from seamless in most (all?) systems. And, to your point, Ted, because much of the metadata connected with ORCID records isn’t publicly available – or there isn’t any – it’s not flowing through systems in the way it could/should in order for everyone to benefit from it. We need to both make it easier for researchers to use PIDs (especially their ORCID ID) and add metadata, and also get PIDs into more systems earlier in the research cycle. It’s a challenge, for sure!