Last week I had the pleasure of moderating a Scholarly Kitchen webinar* with several of my favorite scholarly communications colleagues on one of my — and their! — favorite topics, “Building a Sustainable Research Infrastructure”. Liz Allen (F1000Research), Gabriela Mejias (ORCID) and fellow Chefs Phill Jones (Double L Digital) and Karin Wulf (William & Mary and the Omohundro Institute) shared their thoughts on what a sustainable open infrastructure means to them, provided examples of how that infrastructure is currently working (or not) in practice today, and chose one wish for how to change our research infrastructure.

I think we can all agree that a strong and sustainable research infrastructure — the tools, services, and systems that support the research process — is vital. It speeds up the dissemination of research, helps ensure that it’s FAIR (findable, accessible, interoperable, reusable), minimizes the risk of errors, and reduces the administrative burden on researchers and their organizations alike. But how close are we to making this a reality? What improvements are needed? Who are — and who will be — the key players? What should we be focusing our efforts on and why? Here’s what our speakers had to say…

What does a sustainable open infrastructure look like?

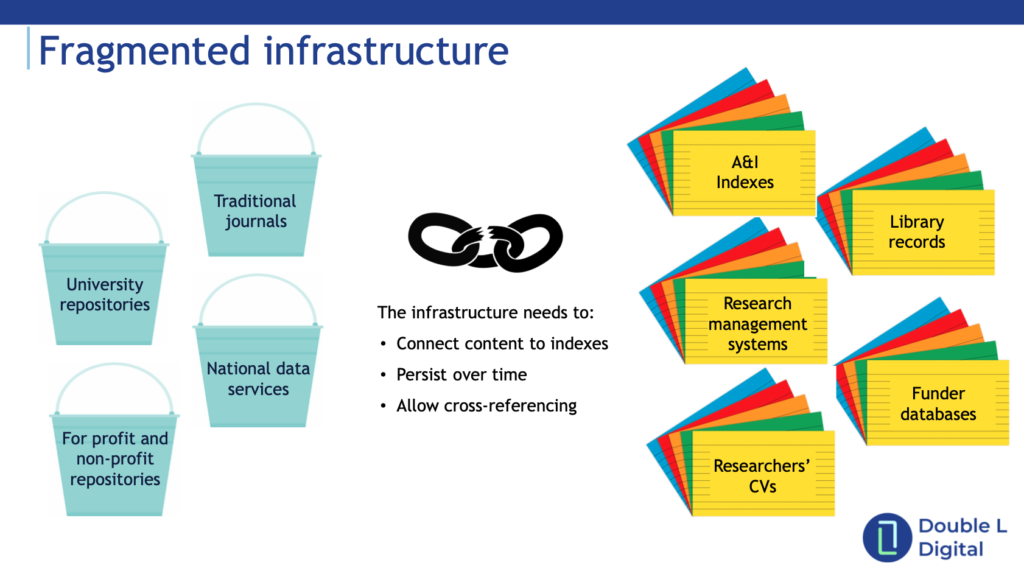

For Liz, a former social science researcher who worked for the research funder Wellcome Trust before joining F1000Research, it’s the foundation of an effective research system, one that will increase discoverability and (FAIR) usability of research, while reducing the current administrative burden and fragmentation of tools and services, in order to benefit research and its impact. Phill, a former science researcher with a publishing background that includes technology and product management, as well as community engagement, was also concerned about fragmentation, and his slide (below) sums up the challenges neatly. He also noted that, in order to be sustainable, research infrastructure requires a multi-stakeholder governance model, openness, and community support and use, as well as financial sustainability.

Gabi, who works for a persistent identifier (PID) provider that is well embedded in the research infrastructure, picked up on several of the same themes. For her, that infrastructure must be open, interoperable, community-driven, diverse, and global in order to be sustainable, and she shared examples of how her organization, ORCID, is a good example of this in practice. Karin, a historian who not only carries out her own research, but also runs an institute that both funds and publishes work on early American history, challenged us to consider whether science is more important than history — or the humanities more broadly — when it comes to research infrastructure. So much of that infrastructure has been developed to meet the needs of scientists, but historians work very differently. For example, the research materials they use are typically in a special collections library or archive; their outputs include workshopped papers, often created at a conference or seminar; and their editorial processes are much more intensive and collaborative than is the case for most scientists.

We also asked attendees to share their thoughts on what a sustainable open infrastructure looks like and you can see the diversity of response in the word cloud below. There are some interesting tensions here — for example, infrastructure should be free and yet it’s also expensive; it must be both independent and regulated; and it requires both flexibility and standardization. No easy answers here, then!

Examples of infrastructure that is currently working (or not!) in practice today

Interoperability was a key theme here. Both Liz and Gabi mentioned Crossref and ORCID as examples of this working in real life, including the auto-update process that enables researchers who use their iD when publishing to have their ORCID record automatically updated. Phill’s example, which also focused on interoperability, was CORE, a service which aggregates open access articles (more than 181M as of today) from around 10,000 repositories worldwide, as well as providing APIs for text mining and access to content and data. For Karin, though, interoperability is less important, because much of humanistic inquiry is taking place between humans, in person. Liz also noted that one of the most important issues that needs to be resolved is what we collectively define as ‘research infrastructure’ — do we all mean the same thing when we use the term and are we all clear (and do we agree) on what the priorities for moving forward? And, if we can agree on what’s included, how do we secure funding to support research infrastructure in the long term. And the fragmentation of initiatives aiming to address/redress inadequacies in and/or build new infrastructure/s came up again here, especially as it relates to long-term sustainability.

If you were granted one wish for how to change our research infrastructure, what would it be?

Once again, a clear theme emerged here, this time around PIDs. Phill’s wish is for “a set of well-governed, well-adopted interoperable persistent identifiers with appropriate metadata…starting with an institutional identifier.” Gabi, even more ambitiously, wishes for more PIDs, including for organizations (ROR), grants (DOI, PURL), projects (RAiD), conferences (DOI, Accession number), instruments (DOI, RRID), and cultural artefacts (DOI, URN). Plus ORCID iDs, of course! And, just as importantly, Gabi also wants communities to actually use these PIDs. Karin noted that ORCID is already a good example of her wish (or two!) for flexible tools that can be scaled down as well as up, and for processes that are mutually coherent but in which interoperability doesn’t require flattening out critical diversity of research or publication. Liz had a slightly different take, wishing that — if we can define it properly! — research infrastructure should be considered an essential part of the research process from the start of the process. This will necessarily require enhanced cross-sector dialogue and harmonization around requirements such as developing common standards (e.g., around the descriptors we use for things like peer review, research grants, and research outputs) to enable interoperability across systems.

When we put the same question to our attendees, PIDs were top of their list too, along with community engagement and adoption.

Takeaways

Considering the wide range of communities and interests that our four speakers represented, there was a remarkable and reassuring level of agreement between them about what’s important, what’s working, and what needs to change. As a PID person myself, I was delighted that persistent identifiers came up (ahem) persistently as key to a robust and open research infrastructure. While there is certainly more work needed to harness their full potential, PIDs like DOIs and ORCID iDs are already enabling interoperability between the many systems and services researchers and their organizations are using. There was also agreement among the speakers that more work is needed to increase community awareness, adoption, and use of PIDs, and of the research infrastructure in general. Fragmentation of the infrastructure is an issue here as it’s virtually impossible for anyone to keep up with the myriad of researcher tools and services out there. Bianca Kramer and Jeroen Bosman’s ongoing work to track these tools makes for a scary read, and the thought of finding a way to make all of them sustainable is even scarier! But at the same time, as Karin pointed out, we need to ensure that the tools we do choose to use and support meet the needs of researchers across all disciplines — and that doesn’t mean just retrofitting tools that were originally developed for scientists, it means developing tools that take the requirements of different disciplines into account from the start.

Whether or not you joined the webinar yourself, we’d love to hear what a sustainable research infrastructure means to you, what other real-life examples you can share, and what changes you think are needed.

*A recording of the event will be available here 90 days after the event

Many thanks to Liz, Gabi, Phill, and Karin for their great talks and for reviewing this post

Discussion

5 Thoughts on "Building a Sustainable Research Infrastructure"

For all of you interested in open infrastructure, I would strongly encourage you to follow, or better yet, engage with the work of the Invest in Open Infrastructure initiative (IOI https://investinopen.org). This is an international group working on the issues this post identifies.

https://aarc-project.eu/ is/has been doing nice work in the field of ‘IT architectures’, identifiers, expressing group information, research proxies etc. The project has follow up via https://aarc-community.org/about/aegis/ and https://fim4r.org/ .

Thanks both!

Hi, Alice, your topic is a very interesting and useful project from research to publishing , scientific evaluation areas that are looking forward to the way to open science. Of course, which is also a big project. Maybe NISO needs to promote this work. Many thanks for you fast to share the Scholarly Kitchen webinar here.

I believe that it is also important to invest in evaluation policies that are appropriate to new practices, seeking an alignment between what is desired, what is accomplished and what is evaluated.