Editor’s Note: Today’s post is by Matthew Salter. Matthew is the Founder and CEO of Akabana ConsultingLLC, a boutique publishing consultancy that offers strategic publishing, editorial, marketing, business development, and Japanese language services to learned societies, scholarly publishers, educational organizations, and publishing service vendors.

It’s August 1991: In Florida, 1940s screen siren and co-inventor of frequency-hopping technology, Hedy Lamarr has recently been arrested for shoplifting for the second time; Ukrainian-Soviet pole vaulting supremo Sergei Bubka competing in Malmö, Sweden has just broken his own world record to take the event to new heights; and Bryan Adams’ extremely popular but intensely irritating “(Everything I Do) I Do It for You” is clinging limpet-like to its number one position in the Billboard singles chart and driving the author – sweating in an Imperial College lab in the first summer of his PhD – nearly out of his mind. Meanwhile, in his office at Los Alamos National Laboratory, American string theorist and scholarly publishing pioneer, Paul Ginsparg, is about to transform scientific communication forever.

It’s been almost 32 years since the launch of arXiv, the original electronic repository serving the physics, astronomy, and mathematics communities, which revolutionized the way researchers share the results of their work. In the intervening period, the popularity and importance of preprint servers have increased out of all recognition to the point where it is hard to imagine life without them. A driver of, and driven by, the growth of open access, and further accelerated by a more recent focus on public access to government-funded research, preprint servers have proliferated to spawn a plethora of multidisciplinary and discipline-specific preprint repositories – most drawing on the “archive” moniker of the Ginsparg prototype for their name.

But alongside the growth of field-focused repositories, more recently there has been a trend towards developing preprint repositories that cater to communities associated with a particular country or language group. And while scholarship is often said to be borderless, as with real estate, when it comes to preprint servers, increasingly it’s location, location, location.

Regional repositories – right in my backyard

Regional and national repositories provide many of the features of discipline-focused repositories such as allowing researchers to get their newest work in front of a targeted community of their peers swiftly to get feedback, recognition, and to stimulate discussion as quickly as possible. They also provide a venue for researchers to comply with the deposition requirements of their institutions and funding agencies as part of meeting public access and open science goals. However, above and beyond this, regional and national repositories serve as vectors for fostering a sense of national or cultural belonging for scholars within a region e.g., Africa (AfricArXiv), a country (ChinaXiv), or a pan-national language group (Arabixiv). Perhaps most importantly, they also facilitate the posting of pre-prints in languages other than English. Allowing researchers to post in their native tongues, the argument goes, lowers a key barrier to preprinting, thereby accelerating the pace of research dissemination – at least amongst those researchers with the requisite language skills.

However, for all their potential benefits, regional and national repositories sometimes suffer from low uptake by the communities they serve and can struggle to secure sufficient funding to cover even modest infrastructure and administrative costs. They therefore typically operate on a shoestring, frequently relying on the efforts of volunteers who, no matter how well-intentioned and industrious, are placed in the invidious position of having to balance their commitment to the repository with competing demands of full-time academic and institutional roles. Such pressures can prove unsustainable, and in recent years have sadly claimed repositories serving the Arabic and francophone language communities, as well as that supporting researchers in Indonesia. IndiaRXiv, the repository launched in 2019 with the aim of boosting science research on the subcontinent, was forced to pull down the shutters temporarily in 2020 but has since reopened with a new hosting partner.

Here Comes the (Rising) Sun

By now, alert readers may be wondering about one major research nation that so far seems to be missing from the conversation, namely Japan. As mentioned in a previous post on The Scholarly Kitchen, Japan has typically adopted a circumspect and pragmatic approach to matters of open access and open science – at odds with its high-profile position as a first-class research nation – which until recently included the provision of a national preprint repository. However, this anomaly was corrected with the launch in March 2022 of Jxiv – the first fully-fledged Japanese-born preprint server – by the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST), one of the largest public funders of research in the country that sits under the administrative and policy behemoth, the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT). As noted in that previous post, JST and its forebears have occupied a central position in the Japanese scientific firmament for over six decades (its earliest precursor, the Japan Information Center of Science and Technology [JICST] was established in 1957), and play a crucial role in shaping and supporting the research ecosystem of Japan and birthing and raising the next generation of Japanese research talent. JST is backed with a suitably hefty budget of ¥170.6 bn (US$ 1.25bn) in 2022 (an increase of almost 21% on 2021), which accounted for around 8% of Japan’s total academic science budget that year. JST also manages J-STAGE, the national online platform for Japanese journals launched in 1999, which hosts more than 3,500 journals containing almost 5.38 million articles, as well as J-STAGE Data launched in 2020. Such connections make it easier to foster symbiotic relationships between the three services, which, with its allied organizational experience and financial heft, puts JST in a unique position to drive the development of open science infrastructure in Japan.

Behind the mask – Jxiv and the era of COVID

Although to many observers outside of Japan, the appearance of Jxiv was rather sudden, the idea of a Japanese national repository had actually been mooted for some time. However, the initiative gained renewed impetus with the outbreak of COVID-19, according to Ritsuko Nakajima, Director of the Department for Information Infrastructure at JST. “Whilst preprinting expanded rapidly in the early stages of the pandemic, the number of preprints coming out of Japan was relatively small and this concerned us,” Nakajima stated, noting that in an analysis provided by the National Institute for Science and Technology Policy (NISTEP), a leading national research institute charged with providing information and other support for the policy-making process, showed that Japan ranked only 13th in the world in terms of the number of COVID-19 related preprints in 2020. Given that Japan ranked 7th in the number of scientific papers published by any country in the same year, something seemed amiss. “The question then arose of whether a dedicated venue where researchers could post their findings in Japanese or English would help speed up the dissemination of research results within the community” she adds. This was felt to be especially important for encouraging researchers working in commercial environments who, unlike their counterparts in academia, are much less likely to create primary research products such as work reports in English.

Accordingly, with the wind of COVID-19 behind their backs, and with a promise from JST to underwrite minimum launch costs, Jxiv was designed, built, and launched from practically a standing start in under two years, a remarkable achievement for any government organization, where progress can often be glacial. “I don’t think JST had really seen anything like it,” says Nakajima “but then again, no one had ever seen anything like COVID.” Although swift by the standards of government agencies, the launch process included in-depth consultations with over 100 scholarly societies that publish journals on J-STAGE, as well as with scholarly publishing and open science experts and longstanding collaborators like Kazuhiro Hayashi the Director of the Research Unit for Data Application at NISTEP who offered support and advice, though the agency played no official role in the launch of Jxiv even if one of the earliest submissions to the repository was a preprint authored by NISTEP researchers. In its quest to hasten and smooth the launch of Jxiv, JST also reached across the oceans to learn from the experiences of other national repositories such as Brazilian national provider SciELO Preprints. By drawing on the precedent of the open-source preprint platform package developed by the Public Knowledge Project that was already in operation with SciELO and leveraging JST’s expertise in building and operating J-STAGE, the team were able to shorten the development time and reduce costs.

Three years on the rock – one down, two to go.

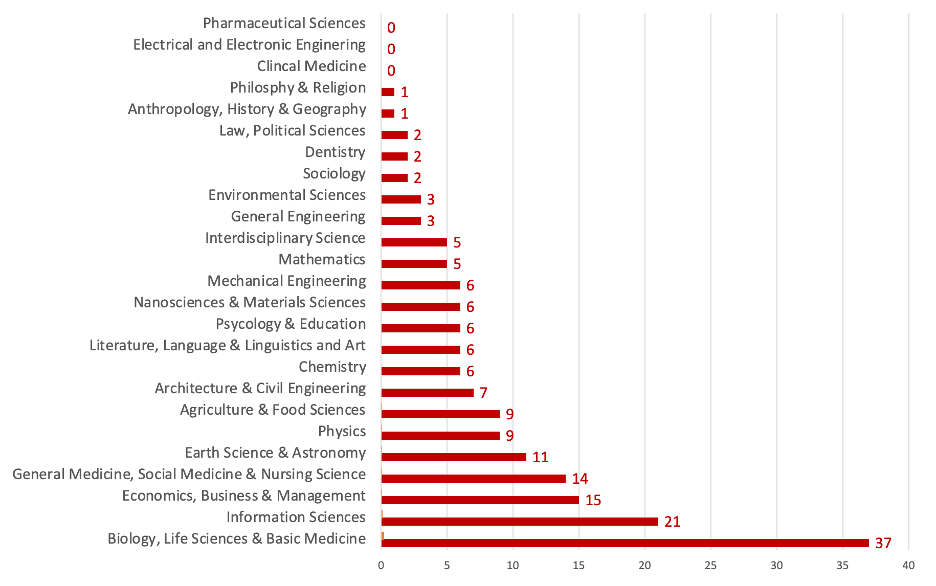

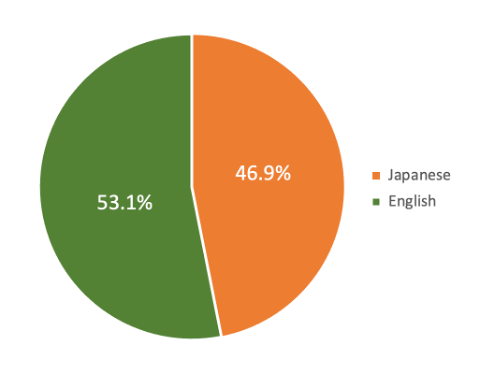

While the launch of Jxiv was generally welcomed by the scholarly publishing community, from the outset some commentators wondered whether Jxiv would seize the imagination of Japanese researchers given the generally low profile of preprints in Japan. And indeed, the pace of growth has been modest: as of May 18th,2023, approximately 14 months after launch, the total number of preprints uploaded onto Jxiv had reached 177, spread across 22 of Jxiv’s 25 subject categories with just under 50% of these concentrated in four categories. Of the total, 53% were posted in English and the remaining 47% in Japanese. According to figures provided by JST, 67% of the preprints have first authors with affiliations to universities and research institutes within Japan, with corporate users and those at Japanese national research and development agencies accounting for 6% and 8% accordingly. Interestingly, 7% of preprints on Jxiv were posted by researchers at institutes outside Japan (based on the affiliation of the first author). Furthermore, while the content currently on Jxiv is somewhat exiguous, it draws a healthy audience for a just-introduced service with the monthly number of views and downloads of content averaging between 4,000-6,000 and 3,000-4,000 respectively, which Nakajima views as encouraging.

“It’s true that growth in the first year has not been explosive, but in a sense that was not our main priority. We are pleased to have succeeded in our initial goals of setting up a viable national repository and expanding the choice of venues offered to researchers to deposit their preprints,” she says. “We’re proud to have taken this important first step, and of course, we’re happy that users are engaging with the content”. Kazuhiro Hayashi offers a similar analysis: “[The first year of Jxiv has been] within my expectations based on my experiences of scholarly publishing in Japan…It’s too early for us to judge the success of this type of preprint server in such a short term…In my personal opinion, it would be a mistake for Jxiv just to try to emulate the history of arXiv,” he says.

The sanguine reaction to the modest results achieved by Jxiv in its first 14 months of operation should not be mistaken for insouciance. Success can take different forms in different parts of the world, and institutions in Japan often take the longer-range view that prizes persistence, and incremental improvement, over short-term results. As with most things in Japan, there is an aphorism that expresses this concept:「石の上にも三年」ishi no ue ni mo san nen (Spend three years on top of a rock) – a person trying to warm a large stone using their body heat knows that it will take time, but that if they are patient and sit tight, results will surely be forthcoming.

Looking forward, Nakajima and J-STAGE platform manager Soichi Kubota identify the general low visibility of preprints and a lack of awareness within the Japanese research community of their possibilities for scientific dissemination as key issues to be tackled in the quest to grow Jxiv. As Kubota explains: “During our interviews with domestic stakeholders on J-STAGE as part of the planning process for Jxiv, we encountered many cases where learned societies were unfamiliar with the role of repositories and had an underdeveloped culture of using preprints. There’s clearly a lot of work to do to raise awareness and change attitudes.”. This second point goes right to the heart of Japanese research culture which, as Nakajima notes, is typically risk-averse, prioritizing caution and certainty over speed, and preferring to publish fully-rounded and thoroughly-confirmed studies, rather than making public preliminary results and conclusions which may later have to be supplemented or modified. “Japanese in general are rather conservative and it takes a while for new trends to catch on,” she says.

“We also accept that researchers in Japan may already be using a preprint repository set up by their community such as bioRxiv, ChemRxiv or even arXiv itself, and we are not necessarily trying to compete with that.” Rather than making it mandatory for recipients of grant money from a Japanese public funder such as JST to post preprints on Jxiv, Nakajima places her faith in more and better communication with Japan-based researchers to get them to incorporate Jxiv into their research program. She points to a recent success in which The Transactions of the Japan Society of Mechanical Engineers has used Jxiv to publish preprints written by researchers from PRESTO, a program funded by JST, for a special issue on complex flow. “We are delighted to have been able to collaborate with PRESTO researchers on this initiative, and we have already received one article,” says Nakajima. “The aim is to have many of the relevant articles available on Jxiv by the time of the next call for PRESTO proposals. Encouraging early publication of preprints is a concrete demonstration of how Jxiv can add value by helping funders to meet their goals. We did not initially envision that Jxiv would be used in this way but welcome creative thinking from the community,” she adds. In addition to local initiatives, JST is counting on global efforts to advance open science, such as the Nelson Memo and the recent statement by the EU Commission as ways to grow Jxiv organically. The final communiqué issued by the science ministers of the G7 nations at the end of their summit in May 2023 is another encouragement.

So, based on its performance in the first year, and with substantial public financial backing, is Jxiv set to defy the trend of regional and national repositories and become a permanent fixture? While admitting that there is no guarantee that funds will be available forever no matter what, Kubota and Nakajima of JST are confident that Jxiv will be given sufficient time to prove its worth and are looking forward to the future. Hayashi too is upbeat about the prospects for Jxiv and hopes that it will develop beyond being simply a repository and add features that facilitate activities such as collaborative writing of research articles, and that tie the platform closer to J-STAGE with the aim of driving symbiotic growth. But before moving in that direction, Jxiv must establish itself fully, although Hayashi admits that without stronger deposition mandates, that might be difficult. “Surviving for at least 5-10 years will be crucial in any case,” he says “and this depends on the will of researchers and research communities in Japan to exploit Jxiv. If they wake up to the potential of preprints and a preprint server in Japan [it will succeed]”. Maybe the best approach is to wait and watch and check in at the end of the decade to see how things are going. With any luck the rock will be toasty warm by then.

Discussion

2 Thoughts on "Guest Post — A Year of Jxiv – Warming the Preprints Stone"

It might be adequate observation that “learned societies were unfamiliar with the role of repositories”, but there is other way understanding that peer-review journals of the learned societies are the place to register scientific findings and share, and they are already established reliable communication.

Also, “an underdeveloped culture of using preprints” could be interpretation that Jxive is the preprint service of the one of the largest research funding agencies in Japan, which rather reminds me of NIH PubMed Central rather than arXive.

The NIH platform is great place to distribute and archive as a reliable source of national funded scientific findings to all. In my opinion, as a long term journal publisher point of view in physical science domain in Japan, there are certain connotation involved in the discussions about preprint services in Japan – if there are clear needs from scientific domains (like learned societies), and if there is a guide by our government that the national preprint service Jxive as a mandated-open access place as a alternative place of repositories managed by institutions or subject domains. This is vital discussions for all who care the future of reliable and sustainable ecosystem.

Hi Mikiko! Thank you very much for your valuable comments. You’re absolutely right that funding agencies and government have a role to play in encouraging researchers to deposit their work in a timely manner into a repository, and when there is a ready-made national option to hand, the process seems obvious. There’s always a balance to be struck between encouraging researcher behavior on the one hand and mandating it on the other – it’ll be interesting to see which way the Japanese government takes things. Also, I like your comparison with PMC, it’s a good point, Thanks again for commenting.