The core element of scholarly communications and what sets it apart from other forms of publishing is its foundation: trustworthiness. Other forms of communication have their own foundations, such as timeliness for news, entertainment for fiction, visual appeal for graphic design or photography publications, or precision in legal communication. Some of the publishing procedures that build this foundation are visible, while others are less so. A great deal of time and effort is spent in the vetting, peer review, and citation practices that are used to buttress the trustworthiness of an argument in a paper or monograph. Ideally, claims are justified either by referencing previous work or through documented research processes that yield data upon which conclusions are based. Knowledgeable experts then vet the claims before publication. In this way, a web of interconnections builds trust into the validity of the published result. Of course, we don’t live in an ideal world and there is no one who will claim that this process is perfect.

Another important part of this network of trust is the process of error correction. When something is determined to be amiss, in error, or even in rare circumstances deemed to be fraudulent, processes exist to rectify the issues. This process in scholarly publishing of retracting, withdrawing, or issuing expressions of concern are another important element of the foundation of trust that distinguishes scholarly communications from other publication genres.

However, there has not been a consistent way in which the community shared, displayed, or communicated the retraction status of a scholarly work, that is, until just two weeks ago, when NISO issued a new Recommended Practice on Communication of Retractions, Removals, and Expressions of Concern (CREC). The aim of the CREC Recommended Practice is to “establish best practices for metadata creation, transfer, and display for both the original publication and the statement of retraction, removal, or [expression of concern], with the goal of facilitating the timely and efficient communication of information to all relevant stakeholders.” Importantly, CREC does not does not consider the rationale or decision-making processes associated with WHY a publication was retracted, removed or an expression of concern (EoC) was issued, since editorial guidance on these activities is already well-established by the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE).

The CREC project was launched as an outcome of the 2021 NISO Plus Conference, where it was one of the top ideas generated by participants. With subsequent support from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, a NISO working group of more than two dozen publishers, intermediaries, librarians, and researchers worked to put forward a set of recommendations.

While some publishers are internally consistent in their representation of retraction notices, consistency more broadly across the scholarly ecosystem is not. Consistent practice across the community is key to ensuring that retracted research is no longer shared and relied upon in research. Professor Jodi Schneider at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign has conducted a number of studies related to the continued propagation of retracted research. Unfortunately, retracted research often sees continued use and citation well past the time it is retracted. CREC Working Group co-chair, Caitlin Bakker, Discovery Technologies Librarian at the University of Regina, and others have also studied retractions in public health literature and the inconsistencies in their representation.

To address this inconsistency, the new NISO Recommended Practice begins by setting forth a consistent set of terminology that is based on existing work by COPE and other industry groups. Building upon this terminology, the working group developed a set of consistent display and naming protocols for how retracted works should be presented to readers. The set of recommendations provides guidance on mechanisms for distributing retraction-related metadata and outlines the publisher’s responsibilities for metadata and associated actions.

For example, as an important first step, publishers should prepend “RETRACTED:” in the title of the paper (in both PDF and HTML versions). Consistent display of watermarks and labels on content landing pages are also important. Retraction notices should be published separately, but freely available, and be linked to the original content which has been appropriately labeled. Guidance on how to completely remove a publication, if that is appropriate is also provided.

A full section in the document describes how various elements of the recommendations should be implemented as well as how to share this information with the ecosystem. That section describes how publishers should endeavor, as appropriate and feasible, to inform those responsible for any associated items (e.g., preprints, datasets, etc.) of the publication’s retraction status. Aggregators, discovery services and preservation services should also receive metadata about the retraction.

The document also outlines a robust set of metadata elements that will support effective propagation of retractions within the scholarly ecosystem. A significant part of the document defines retraction-related metadata elements. Metadata elements are described as either “Essential”, “Essential if Available”, or “Recommended”. For retracted publications, there are 23 metadata elements; eight are Essential, fourteen are Essential if Available, and one is Recommended. For retraction notices/Expressions of Concern, there are defined an additional 20 metadata fields, of which eight are Essential, two are Essential if Available, and 10 are Recommended. Furthermore, these fields are also mapped to relevant JATS Elements/Attributes to ensure clear communication to partners in the metadata supply chain.

In a digital environment, the metadata about the retraction is equally important in the ecosystem of scholarly literature as the online representation. While humans will see and understand the visual cues about retraction status, digital systems rely on the metadata to present search results, present scholarly knowledge graphs, and provide support in citation management systems. Distributing this consistent, machine-readable metadata widely in the ecosystem is critical to limiting the sharing of retracted research objects.

For example, if a researcher notes a paper in her research management software, but it is retracted after that reference is noted, it might still be referenced in the resulting paper. However, if the CREC Recommended Practice is fully implemented in that software, the publication process could automatically check the DOIs of referenced papers for the current retraction status of those works. If a retraction is noted by the tool, that reference could be flagged for removal prior to publication, and if necessary, the background of the paper could be questioned to examine whether the citation is critical to the subsequent work. Some tools already have this functionality, although the retraction metadata to support it isn’t consistently populated. Clarity and transparency is critical in this scenario, more so than the assignment of blame.

The rationale for a retraction may be described within the metadata model, but it’s not required nor is it critical to understanding that a work should no longer be deemed reliable – and therefore shouldn’t be cited for its underlying scientific content. It is recommended that retraction notices include the reason for the retraction, and, when applicable, a notice of publication removal should include a statement that clarifies why the publication is being removed. While potentially useful, a taxonomy of reasons for removal was determined to be out of scope of this project, but might be considered as an element of future work.

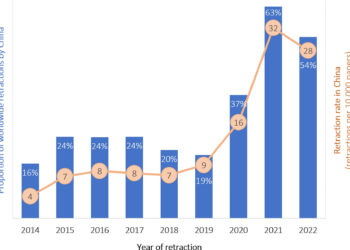

Research integrity has been an important topic of conversation over the past few years, as the pace of retractions has grown and attention on the topic has extended outside of traditional scholarly outlets to mainstream media, such as The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, and others. Scholarly publishers have long taken their role curating the scholarly record very seriously. Adoption of the project’s recommendations will ideally support that mission.

The NISO CREC Recommended Practice is freely available at https://www.niso.org/standards-committees/crec. NISO will be hosting a public webinar about the Recommended Practice on Tuesday, July 23, 2024 at 10:00am ET. Further information and public discussions about the project, both in-person and virtually, as well as additional training materials, will be forthcoming.

Discussion

2 Thoughts on "What To Do Once the Paper is Retracted: NISO Issues Recommended Practice on the Communication of Retractions, Removals, and Expressions of Concern"

Todd, kudos and sincere thanks to you, Caitlin Bakker, the full Working Group, and all who helped make this happen. Standing and applauding.

I am so glad this work is being done. Thanks!!