There is broad consensus in scholarly publishing that AI tools will make the task of ensuring the integrity of the scientific record a Herculean task. However, it seems that many publishers are still struggling to figure out how to address the new issues and challenges that these AI tools present. Current publisher policies fall well short of providing a robust framework for assessing the risk of different AI tools and researchers are left guessing how they should use AI in their research and subsequent writing.

Do publishers really understand what tools researchers are using and how they are using them? Can we do more to create better policies based on real use cases and not hypothetical conjecture about what AI might do in the future? Are there existing frameworks that we can borrow to beef up policy to ensure we continue to uphold research integrity without stifling researcher creativity?

The AI Train Has Already Left the Station Without Us

While scholarly publishers put together committees, organize working groups, and plan conferences to discuss how AI might impact the industry, some authors already are off to the races trying out every new tool they can get their hands on. Recent surveys by Oxford University Press (OUP) and Elsevier demonstrate the prevalence of author use of these tools, researchers’ high motivations for using AI, and even how researchers are using these AI tools.

Sometimes researchers’ AI experiments go as planned, improving quality and efficiency in various parts of their workflow including literature reviews, data analysis, writing and revision, and more. Other times they fall short, leaving researchers with inaccurate or inexact results they must revise using more traditional, “old-fashioned” methods.

But we also need to account for scenarios whereby well-intentioned authors using AI introduce subtle errors that go entirely unnoticed (not to mention the danger of bad actors utilizing these tools to fuel paper mills). And this scenario seems all too likely. While 76% of researchers reported using AI tools in their research in the OUP survey, only 27% reported having a good understanding of how to use these tools responsibly.

Time to Get Our Hands Dirty

A few months back, I bemoaned the fact most publishers have cobbled together a wafer-thin policy on AI tools usage, putting the lion’s share of responsibility and onus for understanding these tools on the backs of researchers. While I would agree that it is primarily the researcher’s or research institution’s responsibility to ensure research integrity (check out Angela Cochran’s treatment of this issue which may have set a recent record for comments on The Scholarly Kitchen), I would at the same time argue that publishers need to understand how these tools work to identify and respond to the myriad of issues that land on editors’ desks surrounding responsible AI tool use.

It is time for publishers to get their hands dirty too, and begin understanding how these AI tools work, with a goal ofdeveloping robust yet pragmatic policies that give authors the freedom to continue to experiment, while at the same time taking steps to set up necessary but not overly restrictive guardrails to ensure that researcher AI experimentation doesn’t go haywire.

Many publishers do seem curious about these tools — the problem appears to be that they don’t know where to start learning. For a recent Academic Language Experts webinar entitled “How Editorial Team are Adapting to the Potential and Pitfalls of AI“, 150 editorial staff from over 40 publishers big and small discussed how authors are using AI tools and got a peek at authors’ favorite tools. Unfortunately, publishers that largely depend on drafting and implementing policies put forth by slow-moving committees and working groups run the risk of not creating relevant policy in a timely manner, leading to problematic science slipping through the cracks of review. Even when publishers do manage to put out more detailed policies, the tools evolve so quickly that they are often out of date even before the policies are announced.

The research integrity issues I’m concerned about aren’t necessarily the outright fraudulent or utterly ridiculous (rat genitalia, anyone?), as most of those should be picked up in review. Rather, my concern is over the non-explicit, subtle extrapolations often made by AI that appear as accurate science even to the well-trained author or reviewer. This could rear its ugly head in the form of a fictitious reference, mistaken data analysis, faulty information, or image manipulation.

Not All AI Tools are Created Equal

Extant publisher policies largely seem to focus on the requirement of authors to make one blanket statement on AI use, thereby chucking all AI tools, uses, and forms into the same bucket. Additionally, most publishers seem to agree that authors should declare any AI use in their submissions to ensure transparency. This “declaration approach”, does not differentiate between how, when, and in what ways various AI tools are being used. The ‘declaration policy’ isn’t nearly enough. Imagine trying to create a singular policy for responsible use of the internet and what that might look like.

In some cases, researchers may not even be aware that the support tools they are using employ AI technology (such as Grammarly for example). A one-size-fits-all approach runs the risk of being overly strict and too demanding in some cases, while being overly lax and too lenient in others.

Substantive vs. Non-Substantive Use & Who is in Charge?

I’d suggest that we need to make a clear distinction between ‘substantive’ and ‘non-substantive’ use. For example, using AI tools to clear up spelling and grammar is clearly a non-substantive use, while relying on AI for data analysis would very much be ‘substantive’. I’m not suggesting that substantive tools shouldn’t be allowed (quite the contrary), but rather that our demands on their reliability and replicability should be higher than currently required in most publisher policies.

In addition, it is worth considering what role the author is playing and what role the AI is playing. There is a compelling argument to make a distinction between the use of generative AI tools to create words, images, figures, or run data from scratch with authors playing more of a quality assurance/reviewer role as opposed to the author being the source of information and using the AI tools to review, revise, and improve on the original draft. But what level of verification do we require from authors when using AI tools to ensure the outputs are indeed accurate? Without providing clear answers to these questions, authors are left confused and frustrated.

Time for Scholarly Publishing to Develop an AI Risk Register?

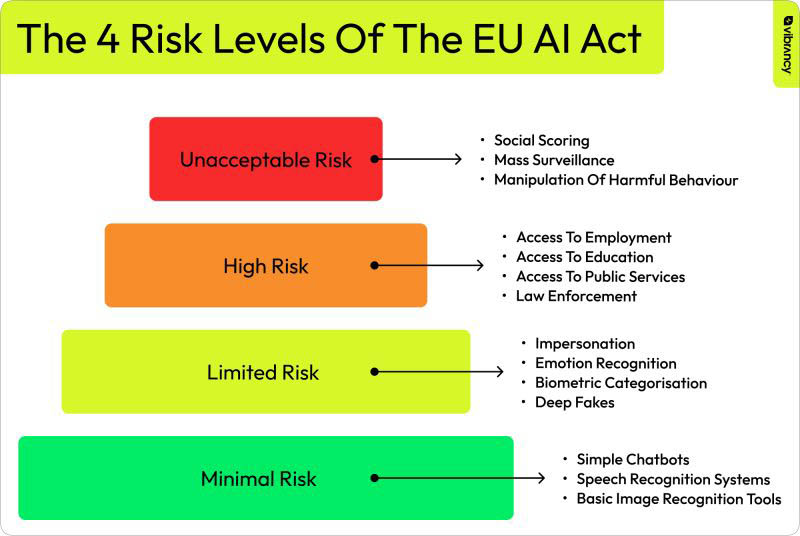

I suggest turning to the EU AI Act as a potential source of inspiration. The AI Act recognizes that not all AI systems are created equal, and therefore, different risk profiles are assigned to different AI tools and use cases, depending on their potential to cause harm, invade privacy, or spread misinformation. The profiles range from harmless to very risky and the corresponding oversight, regulation, and level of transparency required relates back to the potential risks involved.

We may want to consider borrowing and adapting the AI Act model and requiring higher levels of reliability and replicability for riskier use cases within research. For example, Scite, SciSpace, and Elicit can help researchers uncover articles from the published literature that would be hard to surface otherwise. The benefits of retrieval through embeddings and natural language searches are great, with little to no downside to scientific integrity (short of possibly making researchers lazy?). Should authors be expected or required to declare and justify use of these tools for finding the literature they used to write their introduction or discussion sections? After all, authors don’t credit Google Scholar or their university librarian for helping them complete a search.

On the other hand, there are AI tools that assist with the heart of the research itself where the stakes are much higher and the price of a mistake risks spreading misinformation and bad science. Let’s take data analysis as an example. Considering which method should be applied to a specific problem or question can easily skew the results in one direction or another. Is this a decision that we want AI making?

Some new data analysis tools such as (the impressive) JuliusAI can run complex and sophisticated statistical analysis, thus enabling advanced statistical analysis without specialized training. In my view, the onus for oversight and reproducibility when using such a tool ought to go well beyond a simple “declaration” and include a requirement for authors not only share the name of the tool they used for running the analysis but also share the underlying code and demonstrate an ability for others to reproduce the results. Otherwise, it will be impossible to verify and validate the accuracy and quality of the analysis.

Publisher Policy Plan of Action

I’d suggest building a flexible and quick-acting consortium of publishers (one can dream, right?) who would develop living guidelines across the scholarly publishing industry to make clear, coherent, and consistent policies for authors regardless of where they plan on submitting their work. One advantage of the risk register is that it doesn’t necessarily require publishers to learn every tool, but rather requires them to better understand the landscape of tools and creates high-resolution buckets of tools that can be continually monitored and regulated.

Some good resources have already been developed that can be used as a starting point. For example, I’m a core member of the CANGARU coalition which attempts to bring together stakeholders throughout the industry including publishers, universities, researchers, and funders to create a unified policy (unfortunately, the work is painfully slow, risking rendering itself outdated by time of publication). And, of course, the STM Association has put together initial guidelines for addressing AI use in manuscripts.

However, these documents tend to take a more theoretical position and don’t do enough of a deep dive into the real-life use cases that researchers want to experiment with. Therefore, publishers must continually study and learn about the real ways that researchers are using AI tools, including the intricacies of how these tools function, to stay ahead of potential AI pitfalls.

Publishers can improve their approach to AI tool use and policy in the following eight ways:

- Working together to create a global standard framework: agree to a standardized barometer and guidelines for each risk level.

- Making sure guidelines are live and continuously updated: Making sure the guidelines are integrated into standard operating procedures for article submission and peer review processes

- Setting up transparent inclusive governance: Scheduling regular cross-publisher working groups to review and update guidelines and including an exceptions process to resolve matters quickly

- Encouraging experimentation and learning within individual organizations: Creating a continuous learning loop that includes open and frequent communication, a resource library, and training courses.

- Creating a risk register for different kinds of tools: For starters, consider distinguishing between AI discovery, analysis, and writing. Ithaka has put together a wonderful ‘product tracker’ that keeps an up-to-date record of AI tools in higher ed.

- Differentiating between different bucket categories and substantive versus non-substantive use

- Defining who is in charge and whether authors can act as content generators, reviewers, or both

- Considering the ability to monitor and enforce these policies (spoiler: that won’t be easy and may need to be seen as more author education)

By creating more robust policies around the use of AI tools for research and writing, we can genuinely support authorswhile securing the integrity of the scientific record.

A big thank you to Chris Kennally, Thad Mcllroy, Ann Michael, William Gunn, David Crotty, Tommy Doyle, Peter Gorsuch & Chhavi Chauhan for their invaluable input and contributions to previous versions of this article. It is wonderful being in an industry where when you ask for help, people jump to say yes. If you enjoyed reading it, the credit is all theirs.

Discussion

7 Thoughts on "Woefully Insufficient Publisher Policies on Author AI Use Put Research Integrity at Risk"

I wonder if publishers are too slow in writing policies about AI maybe they can try a chatbot?

Ok I’m being cheeky, but the point that bots can help with monitoring the literature or even creating policy drafts is not made.

Why are publishers doing to war unarmed?

Thanks Anita. I’m not sure the writing is the issue as much as a deep understanding of the kinds of tools available and the ramifications of using them within research.

Thanks, Avi, for this great piece. I could not agree more and feel that education of all stakeholders–researchers, authors, editors, and publishers–may be required.

Why are there so few comments here on this important topic? It’s so important to take a stand, for, against, or in the nuanced middle ground.

It’s become kryptonite for publishers. Authors are so angry that most publishers are just hiding, afraid to say anything at all about AI.

Come out, come out, wherever you are.

Thanks for the nudge in the right direction, Thad. There’s a good conversation going on the Linked side: https://www.linkedin.com/feed/update/urn:li:activity:7221852185670668288/ but it would be great to get a convo going in the comments here as well. Maybe we need to run an industry event on the topic.

I just found out that my new book on AI and book publishing was banished from Ingram for containing “content created using automated means, including but not limited to content generated using artificial intelligence.”

https://thefutureofpublishing.com/2024/07/ingrams-filters-mistake-ai-discussion-for-ai-deception/

Thanks, Avi, for this excellent post summarising the issues we are grappling with on substantial AI use within the conduct of research. At the Cochrane Collaboration – an organisation that conducts and publishes evidence synthesis – we’ll soon be sharing draft guidance and recommendations for wider consultation on responsible AI use, in collaboration with other evidence synthesis organisations. This guidance will aim to delineate the roles and responsibilities of the different actors involved in AI use in evidence synthesis (from the AI developer to the general evidence synthesist). Though focused on evidence synthesis, the general approach could be applicable across other types of research. Our aim is for a research ecosystem where informed decisions can be made about AI use to reduce the confusion and frustration authors currently face. To protect the integrity of research, the guidance advocates for human centric AI and considers benchmarks for AI accuracy and reliability, and how we can have clarity on limitations and generalisability. It will evolve over time and we welcome (and would be interested in contributing to!) cross organisation and publisher efforts to provide this type of clarity and guidance for researchers and authors as it’s a new area for us all. And it’s important that approaches across publishers align, otherwise we’ll simply add to the confusion and frustration authors already face.