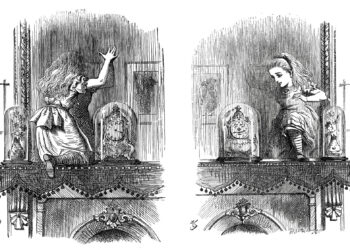

Recently, I argued with myself over whether or not to weed from the family shelves a copy of Owen Wister’s 1902 bestseller, The Virginian. An image of a western saddle appears in gold on front and back covers; the page edges are gilded as well. A portrait of the author serves as a frontispiece. A few pages on, there is the double page spread showing a cowboy sitting on his horse, alone in the western landscape. Pen and ink illustrations break up the chapters. From the publisher’s perspective, this is a physical book worthy of display on a shelf for decades. I might view their investment differently, particularly as I acquired the thing second hand at a bargain price. It is hard to relinquish a leather bound volume, even when I know the words themselves are readily available on Project Gutenberg. What sort of a physical replacement would I be able to purchase nowadays?

The upscale production values I’ve noted are not actual necessities for the reader. Regardless of how long-form content has been packaged in recent years, environmental priorities are currently driving print production in other directions.

The European Union Deforestation Regulation (EUDR) went into effect in June of 2023. Legal firm White and Case provided ten key considerations resulting from that regulation that they perceived as impacting on U.S. companies. While writing for a broader audience than just our own, they noted in passing that providers of printed books would need to be in compliance.

During the Book Manufacturing Institute Annual Meeting in late 2023, a keynote interview with Mary McAveney, CEO of Abrams Books, provided an example of how the EUDR might affect her organization. “We are 100% owned by a French company and are working to understand how the sustainability laws in France will impact us. Do they have an impact on us in the United States? We have a joint agreement with Chronicle Books in the UK where we ship our books to the UK for distribution throughout Europe. How do the sustainability laws there impact what we’re shipping over?” (Note: EUDR requires suppliers to provide the geolocation of the trees used in the manufacturing of paper. As paper supply routinely crosses international boundaries, this degree of tracking becomes complex.)

Enter 2024. A blog entry from the Book Industry Study Group (BISG) provides an excellent overview of what might be seen as the “moving” elements affecting sustainability and the business of publishing. Entitled Modeling The Compounding Cost of Sustainability, the post listed variables such as the cost of carbon, transportation and logistics costs, concerns over deforestation and current paper mill capacity, In considering the most basic challenges associated with paper supply, a talk provided by John Crumbaugh during a BISG lunch-and-learn event was illuminating. Crumbaugh, a Senior Project Manager at on-demand equipment manufacturer HP, noted that in the wake of the pandemic, demand for specific paper categories (uncoated free sheet, coated free sheet, coated mechanical, etc.) was shifting – with a corresponding shift being seen in mill capacity. For some types of paper, current capacity in North America was half of what it had been in 2018. At the same time, getting approvals for construction of new paper mills (however much needed) would be challenging due to concerns over the environment.

A March blog post from BookNet Canada included one publisher’s prediction that in roughly a decade, we would see “regionally based print-on-demand (POD) printers that print on alternative, next-gen paper sources local to their regions.” In terms of pricing, the same publisher went on to say “Carbon taxes on books printed on virgin wood fibre paper will be high in order to capture and illustrate the full cost of these titles and taxes collected will be returned into the next-gen paper and publishing industry.”

Following social media posts from the London Book Fair. I happened to see an event attendee quoting Cambridge University Press (CUP) as saying that 85% of their frontlist was currently produced as print-on-demand (POD) and their goal was to raise that percentage to 95%. That was an impressive statement and I asked the poster about the drivers behind it. A quick response came: “Environmental and carbon footprint considerations with a focus on reducing returns, overprinting, and overstock”. The Press wanted to reduce their carbon footprint; this goal was part of the press’ larger sustainability framework. The energy demands associated with paper, ink, and binding required scrutiny. Further back-and-forth yielded a comment that the particular CUP titles affected were generally selling in lower quantities and the 5% not handled via POD were those titles where sales volume made POD inefficient in satisfying market demand.

A subsequent tweet quoted Vertebrate Publishing’s stated approach to sizing print runs. Their frontlist titles would be initially printed at a very low number (say, 200) and only once market demand was known, would a larger print run be authorized. The strategy was working well for them, minimizing the hazard of unsold inventory.

Whether through close scrutiny in setting a print run or by building awareness of sustainable typography, the publishing environment has been focused on making these types of practical adjustments.

In June, the Oxford University Press Responsible Publishing Report provided evidence of some of the ways in which the organization had altered their practices, specifically with an eye to environmental sustainability. Ninety percent (90%) of the paper used by the Press in 2023 was certified as coming from sustainable sources. The press anticipates anticipates that, by 2025, 100% of the paper used in their print publications will be from certified sustainable sources.

Another shift referenced in their practices was the replacement of a PVC book protection film used on the cover of a best-selling title with “a paper-based, flexibound cover”. Elsewhere on the OUP site, a blog post further explained that, “the flexi-bound cover material is more sustainable and it reduces the manufacturing challenges and print quality of the product. Making this move from PVC to card cover eliminates 15 to 20 metric tonnes of plastics annually.”

In an interview posted to the GreenBook Alliance website, Kim Werker of Nine Ten Publications, a independent niche start-up, listed sustainability priorities for her company:

- shipping/fulfillment direct to consumer,

- print runs (not overprinting),

- staying local wherever possible, and

- scaling.

Asked a follow-up, she said,

I’m always thinking about what do we absolutely need versus what we just want...When it comes to print runs I’m always thinking about not having to print again (because of the economy of scale of printing books) and I only want to pay the freight run once.

Those daily engaged with manufacturing processes are already aware of the challenges faced by content providers. The State of the Industry 2024 report released by the Book Manufacturing Institute offers a useful assessment of both existing pressures and available solutions. From a domestic standpoint, the North American members are well able to ensure the provenance of the paper supply, keeping the carbon footprint within check. Print remains a necessary format option and they continue to establish appropriate manufacturing standards.

I share these various bits with the Scholarly Kitchen readership as documentation that the sustainability issue is of significance to publishers, absorbing attention and workday energies. Whether you look at trade or academic publishing, professionals continue to assess how the print product may be usefully delivered, partnering across the supply chain to minimize any environmental impact. Innovation is happening but in equal measure with pragmatism.

My husband rescued The Virginian. The collector’s edition never made it into the donation box. But for him, retention was about reading. When an author has touched a reader, packaging is less of a priority. He’d have settled just as readily for a mass-market paperback.

What’s important is allowing serious readers and researchers the on-going option of physical print. We don’t need to sacrifice the environment but neither should we sacrifice the value of what’s held in the reader’s hand.

Discussion

7 Thoughts on "Ensuring the Sustainability of Print"

All very good stuff, but it’s important to remember alongside this the similar environmental cost of digital publishing and online infrastructure. As I understand it, the environmental cost of an ebook versus a print book is still very much debated, which tells me that there’s not much in it. As long as they’re doing what they can, print book publishers shouldn’t feel specially guilty. Printing books is a drop in the (rapidly warming) ocean compared to what the tech giants are doing to the environment.

Reaganomics rears its head again in 2024! The pulling of federal support from academic libraries sealed the fate of printed scholarly books. It is the law of supply and demand. The demand for scholarly books on specific narrow topics is minuscule. Thus, publishing them demands a high price and further narrows the market.

Thank you for this, Jill. “What’s important is allowing serious readers and researchers the on-going option of physical print. We don’t need to sacrifice the environment but neither should we sacrifice the value of what’s held in the reader’s hand.” Offering options to the reader is the core takeaway. The options of POD and digital allow publishers–especially smaller, leaner, nonprofits–to keep books in print and available. POD supports sustainability in more ways than one.

One complaint I’ve heard from a small US-based academic press is that the new EU regulations require them to have someone physically located in the EU to answer consumer questions about safety issues with their products. A new, remote employee is not feasible for them, and for me, I’m really curious about the potential safety issues (“don’t drop it on your toe” or “beware of new ideas”).

That doesn’t surprise me. Big Business always colludes with government, fueling their insatiable appetite for bureacratic over-reach by encouraging them to add ever more burdensome regulations. This is how they drive out smaller competitors and make the cost of market entry so high it deters new market entrants. This unholy alliance of the most rapacious capitalists and the most authoritarian Left find their most fertile territory in the realms of Health & Safety, ESG and DEI.

David, I strongly agree with you.