Editor’s Note: Today’s post is by Christos Petrou, founder and Chief Analyst at Scholarly Intelligence. Christos is a former analyst of the Web of Science Group at Clarivate and the Open Access portfolio at Springer Nature. A geneticist by training, he previously worked in agriculture and as a consultant for Kearney, and he holds an MBA from INSEAD.

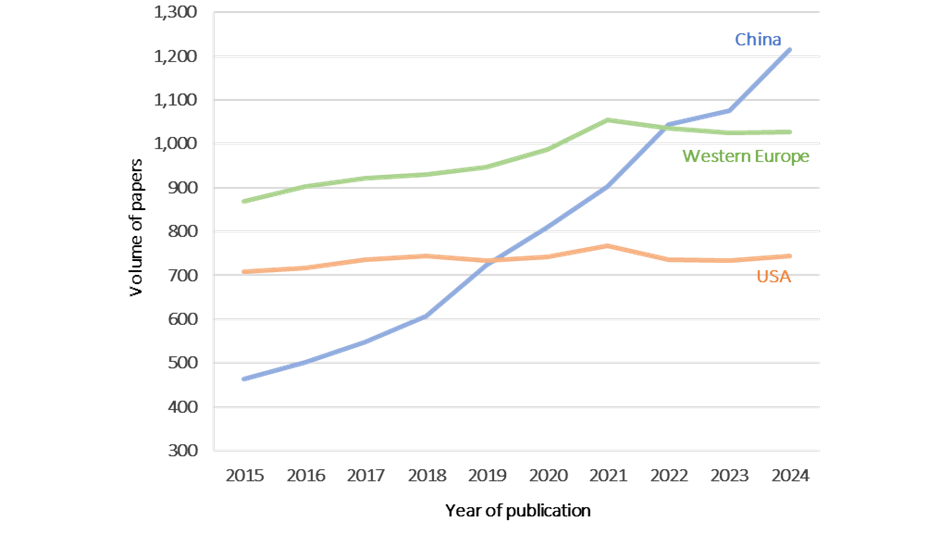

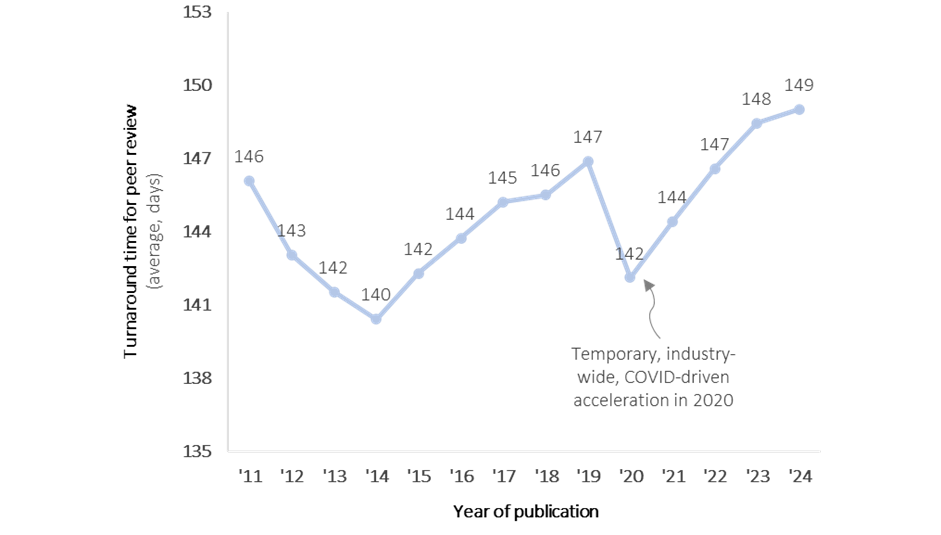

China is dedicating an increasing share of its growing GDP toward research. In just ten years, it jumped from publishing fewer papers than the US to 60% more. Meanwhile, the volume of (predominantly western) editors and reviewers has hardly grown. What happens when an ever-growing supply of papers collides with an ever-static supply of editors and reviewers? For starters, it leads to a global slowdown of peer review of nine days in the span of ten years. Bringing together volume, turnaround time, retraction, and several other pieces of data, this piece argues that we are sleepwalking toward an avoidable breaking point.

While China thrives, other countries stagnate

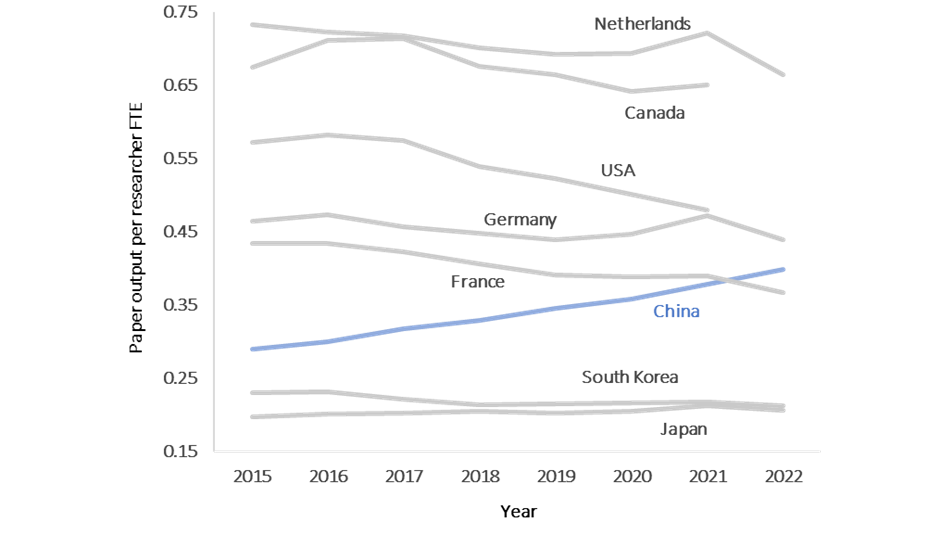

In 2015, China’s research output was 34% smaller than that of the US. A decade later, it has become 63% larger. This is the result of growing by 11.3% annually (from 464k papers to 1,216k) in comparison to the US’s 0.5% (from 709k papers to 744k). More broadly, the paper output of most countries with developed research ecosystems has been largely static, while that of China has been surging.

In several categories within Physical Sciences and Engineering, Chinese research output has overtaken the quantity emerging from the entire Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), which includes the USA, the UK, Germany, France, Japan, and 33 other countries. We should probably get used to news about Chinese breakthroughs such as long-lasting batteries for EVs, AI models that rival western ones at a fraction of the cost, or jet fighters that go toe-to-toe with the best that the west has to offer.

Meanwhile, the White House’s draft budget for fiscal year 2026 would slash the funding of the NIH by 40% and that of the NSF by over 50%. The likelihood of the USA reducing its research spending can further boost China’s stature.

A mixed bag of “gifts”

By most accounts, the growth of Chinese research is a gift to the world. And to western publishers. Whether in Open Access or in subscription format, paper output is the currency of scholarly publishers. The growth of Chinese research has meant that publishers have many more clients, either in the form of subscribing institutions or in the form of APC-paying authors.

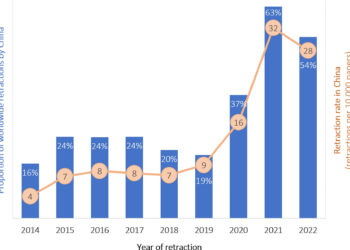

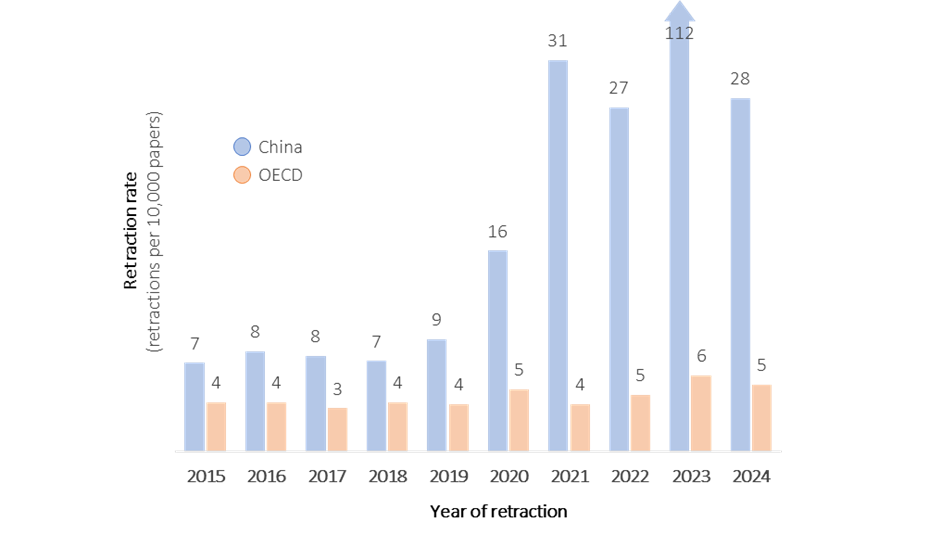

By other accounts, the growth of Chinese research has not been trouble-free. The retraction rate of China dwarfs the retraction rate of the OECD, requiring publishers to strengthen their editorial processes, lest they get devoured by papermills, as happened to Hindawi. In some medical fields, more than 1% of Chinese papers end up with a retraction.

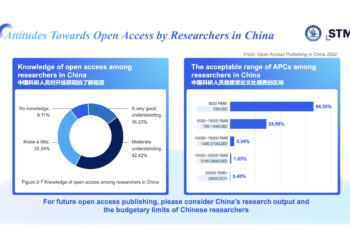

The growth of Chinese research has also translated to less clout for western policymakers. At the time that Plan S was conceived, the paper output of Western Europe was about 300k papers larger than China’s. Now, it is 200k papers smaller. Europe’s ability to influence the business decisions of publishers, such as the transition to Open Access via Plan S, is diminishing. A transition to Open Access is now largely in the hands of Chinese policymakers, especially for categories in Physical Sciences and Engineering.

Let editors eat cake

I would hazard a guess that typically western-based editors and reviewers are the least enthusiastic group of research stakeholders concerning China’s growth, as they are asked to contribute more than what is fair.

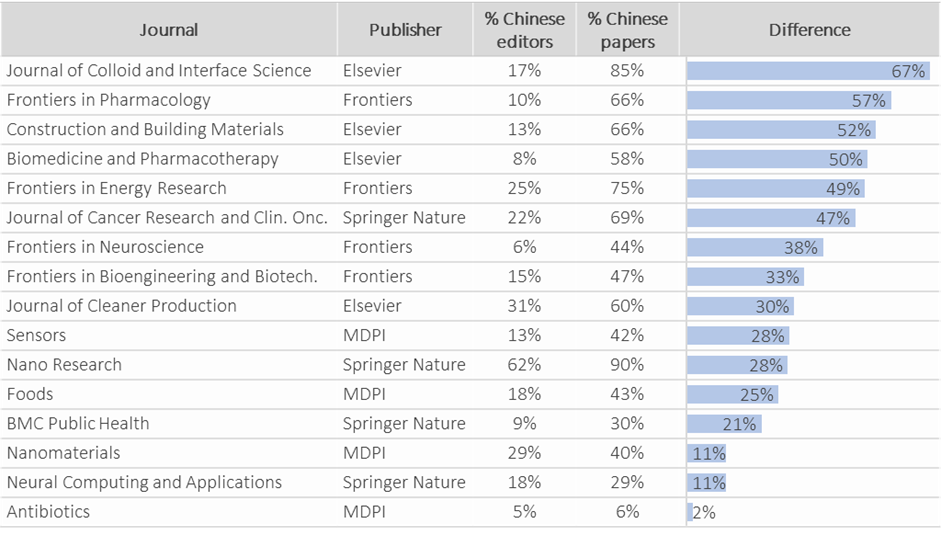

The data shows that Chinese editors are under-represented in editorial boards. They accounted for a smaller share than Chinese papers in all of 16 sampled journals (a mixed bag of large STEM journals across publishers). In more than half of the journals, China contributed a three times higher proportion of papers than editorial board members.

More Chinese papers means more requests and more time spent editing and reviewing papers for western-based editors and reviewers. And western publishers grow their business at the expense of harder work by editors and reviewers. And no, paying reviewers is a bad idea.

I will hazard another guess: opening the gates to Chinese editors and reviewers has not been the strategy of choice for fear of potential triangulating across Chinese researchers, editors, and reviewers, thus increasing the odds of misconduct. I do not subscribe to this approach, but I view it as rational and practical, especially in high-risk medical fields.

China grows, everyone slows down

Today, papers are accepted at their slowest rate since at least 2011, and nine days slower than in 2014 (based on 8m papers of 16 major publishers, excluding MDPI). I believe this is driven by the growth of Chinese research that has (a) pushed western editors and reviewers beyond their optimal utilization point and (b) forced publishers to introduce more editorial checks to combat Chinese papermills at the expense of efficiency.

The slowdown is near universal: 11 of 12 sampled publishers were slower in the second half of 2024 than in the first half of 2021.

The effect of editor and reviewer scarcity on turnaround time can only be proven with in-house publisher data. My working assumption is that the growing imbalance between Chinese editors and Chinese papers has meant that it takes longer to assign an editor, longer to find reviewers, and possibly longer to edit and review because of the language barrier.

On the other hand, the effect of additional editorial scrutiny on turnaround time should be easier to gauge. For example, as I previously reported, the journal Frontiers in Oncology slowed down shortly after the papermill scandal at Hindawi.

It should not have been this way. Technological innovation should have enabled peer reviewing to become faster, or at worst remain steady. Nine days of a slowdown in ten years might not seem noteworthy, but it translates to more than 80,000 years of wait-time annually for papers with valuable information hidden in inboxes. And this drama is far from over.

All gas, no brakes

There is reason to believe that China’s paper output will continue to grow apace for years to come. Perhaps it will not achieve annual rates of 10%, but it can maintain its annual absolute growth of around 100k papers, in line with its performance from 2019 to 2024. The three drivers at work are (a) the expected growth of China’s GDP, (b) China’s growing spend on research as a percentage of its GDP, and (c) its growing paper output per researcher FTE.

The IMF forecasts growth between 3.4% and 4.2% for China’s real GDP (adjusted for inflation) from 2025 to 2030. This might not sound as impressive as the 7%+ rates that it sustained pre-pandemic, but the growth is similar in absolute terms, and it can likely support 100k additional papers annually.

In addition to growing its GDP, China aims to spend a growing share of it on research and development (R&D). It currently spends a smaller share of its GDP on R&D (2.6%) than some of the world’s research leaders such as the US (3.6%) and the UK (2.9%). China’s goal is to increase its spend to 2.8% by 2030. This is not overly ambitious, as it would bring China closer to other research leaders. It translates to 1.1% annual growth of R&D spend under constant GDP.

Last, the paper output per researcher appears to be static or declining in a selection of developed countries. Yet, it has been consistently growing for China at an annual rate of 4.7%. This may reflect that, despite its large size, Chinese research is still at a developing stage. Until the output per researcher reaches a plateau, it will be contributing to the growing paper output from China overall.

Meanwhile the volume of researcher FTEs in developed countries has been growing at low single digits. If this trend continues, it will widen the gap between China’s paper supply and the availability of editors and reviewers from western countries, overwhelming journal pipelines, fueling frustration across stakeholders, and bringing western publishing to breaking point.

Research misconduct: a feature or a bug?

China appears to be making a concerted effort to stamp out papermill activity and combat research misconduct. A nationwide research misconduct audit in 2024 has been followed by public naming and shaming by the Ministry of Science and Technology. Most recently, the country’s top court urged a nationwide crackdown on papermills, signaling that such services may soon face criminal penalties.

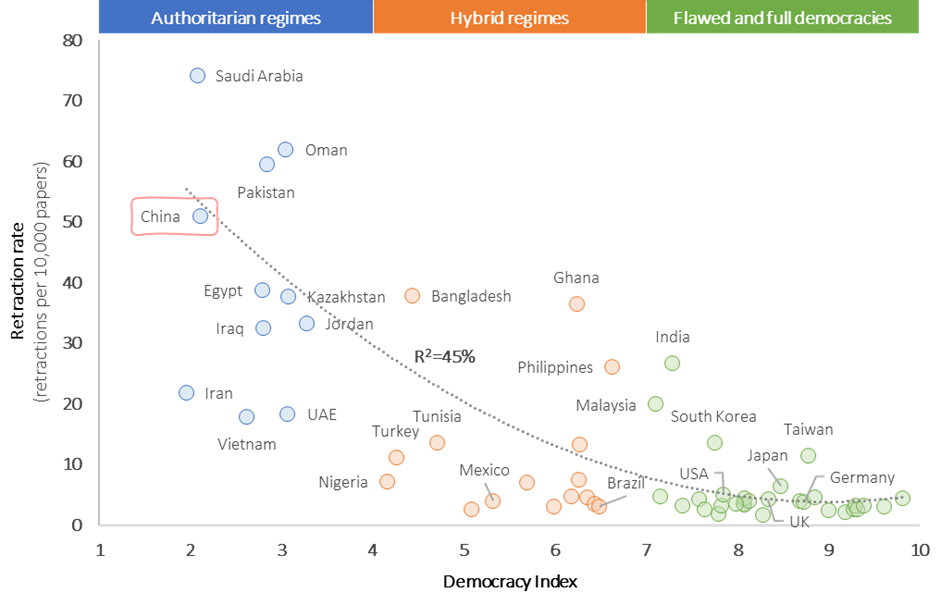

Were it to bring its retraction rate in line with the OECD countries, China would be the only authoritarian regime to do so. The coupling of retraction rates with data from the Economist’s Democracy Index shows that countries marked as authoritarian (Democracy Index score below 4.0) have a retraction rate three to 30 times higher than the OECD.

The data shows that China has an uphill battle in combatting research misconduct. Everyone should cheer the country’s effort to prove that misconduct in non-democratic countries is a bug, not a feature. Until it does so, the inclusion of Chinese researchers in the international publishing ecosystem will be viewed with skepticism.

Yet, it is not all doom and gloom. China’s retraction rates in several areas are low and in line with those of western countries. For example, in Chemistry, and Physics and Astronomy it retracts four and two papers every 10,000, respectively. Such areas should form a platform for the inclusion of more Chinese editors and reviewers in publishing.

Unsustainable bottlenecks or sustainable publishing

Whether we are heading to a future of unsustainable bottlenecks or sustainable publishing hinges on the inclusion of Chinese researchers in the western publishing ecosystem and the emergence of a large and reputable Chinese publishing ecosystem. In turn, these depend on (a) the ability of China to combat research misconduct and (b) the adoption of people-empowering technology by publishers.

However unlikely, China addressing its research misconduct issues will eventually lead to an improving reputation across research stakeholders. Chinese editors and reviewers will be more welcome in western journals, and international authors will be more willing to submit their papers to Chinese journals. Both are necessary for a future of equitable, inclusive, efficient, and reliable publishing.

Technology has a role to play too. AI-driven innovation can raise the productivity of editors and reviewers, e.g., by providing structured review templates or by assessing the quality of human reviews. It can also be used by publishers and editors to effectively sniff out misconduct, reducing the risk of engaging with editors and reviewers from any country, including China.

Instead, if inertia prevails and no stakeholder takes action, we are heading to a future of slower, more costly, and more frustrating publishing to the point that authors are pushed toward fast but unreliable publishers.

Discussion

14 Thoughts on "Guest Post — How the Growth of Chinese Research Is Bringing Western Publishing to Breaking Point"

I agree with the general message of this piece, but strongly disagree with the apparent assumption based on Figure 10 that countries with high ‘democracy indices’ (whatever this really means) are somehow *more ethical* when it comes to research integrity (as inferred by relatively low retraction rates).

It is clear for a long time now that many western countries *actually face major difficulty* in facing up to the realities of their own research misconduct – be that by painfully and unnecessarily long times for what are often fairly straightforward investigations, apparent denial of facts by influential figures, the competing interests of institutes, their senior leadership and their respective reputations, reluctance to report or nark on colleagues or superiors, or weak or non-existent internal frameworks and avenues to report and investigate such allegations.

The following are only a small handful of recent and/or high-profile RI cases from the life sciences that are frankly riddled with competing interests that are part and parcel and an apparently accepted part of life and research culture in so-called ‘liberal western democracies’: Jonathan Pruitt at McMaster Uni, Marc Tessier-Lavigne at Stanford, several labs with data fabrication at Dana Farber Cancer Center (US), Olivier Voinnet at ETH Zurich and CNRS France, several western Nobel Prize winners – including 15 retractions from Gregg Semenza at Johns Hopkins University. Shall I continue?

In other words, the data for relatively low retraction rates in high-democracy-index countries could easily be interpreted as an ongoing reluctance to investigate and take action on account of the aforementioned cultural features. Westerners need to face the music too. This is missing from this piece and merits inclusion in future discourse on this broader issue. China isn’t is ‘bad’ as it appears…

Jared, I appreciate the thoughtful comment. Figure 10 is strictly empirical: retractions per 10,000 papers. On that basis the OECD sits at ~5/10,000, China at ~50, and several other low-democracy countries are between ~15 and ~85. This three- to ten-fold gap is hard to explain by detection lag alone. High-profile western scandals show no system is perfect, but the size and consistency of the disparity still matters.

Sorry, getting a bit late where I am based. This meant to read: a rate of ~15 to ~75 for other low-democracy countries, and a three- to fifteen-fold gap…

I seem to recall that there was a time that Chinese researchers had enormous pressure to meet very high publishing targets, so there was enormous incentive to “cheat”. I also thought I had read that the Chinese govt had changed that incentive structure to improve the situation.

I was hoping this post would give us an update on that, but unless I somehow missed it, it’s not here. Certainly from the data here it looks at least like the Chinese researchers do not have an incentive to participate in the editorial/review side of scholcomm. I’m not sure what to make of the comment about “triangulation” – that sentence is written in a way to deliberately obscure WHO in scholcomm is thinking about this and making decisions on the basis of that concern.

But clearly, the scholcomm system as currently operating can’t sustain a huge influx of submissions without a balancing influx of volunteers on the editorial side. I am concerned that this will lead to pressure to accept more AI involvement in the peer-review process. Having just read a disturbing article about the concept of “prompt injection”, I don’t think we’ll get to the point of having a trustworthy AI-involved PR system fast enough to handle the influx this data presents. I think the short/medium-term solution has to be either walling off Western publications from Chinese researchers and force them to create their own entire system of journals where they have to deal with the volume of work themselves (not a position I advocate), or we need to find a way to convince the Chinese govt to provide more incentives to Chinese researchers to participate in the editorial side. Maybe just the threat of the first option would be enough to compel action on the second?

Hello Melissa, my understanding is that the absence of Chinese researchers from editorial boards is less about their reluctance to participate and more about the reluctance of western publishers and researchers to extend invitations. Springer Nature, for instance, added 3,000 Chinese editors in 2024 alone after a targeted drive (https://www.springernature.com/gp/researchers/the-source/blog/blogposts-for-editors/actively-supporting-our-editorial-boards-in-china/27787734).

I think we agree that the inclusion of more Chinese researchers in publishing is the best option going forward. I just don’t see it happening overnight. First, publishers will need to be more confident about their capacity to spot misconduct and/or China will need to defy the odds and address its endemic misconduct issues.

Thank you for sharing your thoughts, Melissa.

However, I would express some concern about the idea of “walling off” Chinese researchers or encouraging the development of a separate publishing system. The mission of scholarly publishing is to facilitate the global exchange of knowledge, and academic openness remains a core value shared by the international community.

When a research system grows as rapidly and at such scale as China’s, it’s understandable that challenges including issues related to integrity become more visible. But many of these issues are not unique to one country. They exist across the ecosystem and are simply magnified in proportion to volume.

From what I’ve seen, Chinese policymakers are taking meaningful steps to address research integrity including through policy reforms, oversight mechanisms, and the development of related technologies. Rather than drawing lines, I believe the most constructive path forward is collaboration: working together across borders to improve the systems, tools, and standards we all rely on.

We’re facing shared challenges in a shared space, and that calls for shared responsibility.

I agree, as I noted that I don’t advocate that but could imagine using the possibility as a “threat” to get the Chinese govt to do more to incentivize the editorial part of that “shared responsibility”.

Melissa, would you please share the citation for this article? “Having just read a disturbing article about the concept of “prompt injection””

https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2025/07/04/japan/ai-research-prompt-injection/

I only saw it because it was featured in Gary Price’s wonderful free e-newsletter, Infodocket, which I highly recommend. After reading it, I did some googling about “prompt injection” and there’s a huge amount but most of it is about server/service security, not academic issues.

I have noticed that in my field, the proportion of papers from chinese institutions is much higher, and they are very well-written, unlike the papers I reviewed in the 2000s. So, Chinese scientists have done a great job of improving over the past decade. It’s not perfect, but no worse than Western papers. The breaking point: I predict that English will be replaced by Chinese as the language of science in the future (not so far). Of course, papers in both languages will coexist, but to be up-to-date on scientific advances, you’ll have to consult papers written in Chinese. This is something that I do, and you will be surprise (thanks to Google translation). It’s like hundred years ago, when French or German were replaced by English. Be ready my dear English fellows (USA/British) to lose your hegemony.

This is a fascinating take. I do not think it has been implemented anywhere yet, but wondering whether universal translation has a role to play here. If researchers are willing to translate articles themselves in order to capture the entire literature, perhaps that can be done more systematically by publishers or other services.

I am academic adjacent and I suspect that the problem isn’t just about not enough Chinese editors. As I understand it, in many fields the actual reviews are frequently not done by the editors. Instead, the editors farm them out to trusted colleagues/students to do the reviews. It may take a while before non-Chinese editors develop a list of people they trust at Chinese institutions. Since reviewer info is generally not public it would be difficult to see how much of this is at issue. Anecdotally, I’ve heard editors say they no longer ask for reviews from Chinese people who haven’t been recommended because the result is too often “this paper is perfect and should be published immediately”.

Higher education in China requires a reasonable understanding of English as a prerequisite, so there may not be as great a language barrier as assumed. In using online translation though, be very careful, many words can have different meanings in different contexts and AI is likely to use the most common context rather than a usage in a particular field of study. At the very least, translate back and forwards again and see if it still means the same. China will not be bullied into taking a course of action, but does respond well to constructive criticism. I think that it would be good for China to create its own journal system, if only as a filter to front-end worldwide submission. It would introduce some delays, but quality is more important than quantity and reputation is more easily lost than gained.