In academic publishing, numbers have become the shorthand for authority. An impressive Impact Factor or a high citation count signals credibility at a glance. For decades, these metrics have been used to guide decisions on funding, hiring, and promotion. But somewhere along the way, what began as a means to measure quality has started to dictate the very shape of research itself.

Today, the scoreboard often overshadows the substance. Researchers are not only aware of the numbers, they are actively shaping their work to achieve them. And the more these metrics are chased, the more they risk distorting the very thing they were meant to measure.

Warning Signs in Plain Sight

The consequences of a metric-obsessed research culture are becoming difficult to ignore. In an environment where citation counts, Impact Factors, and publication volume heavily influence career advancement, some researchers and even journals may prioritize output over quality. This pressure can create fertile ground for unethical practices, such as paper mill submissions and manipulated peer review, both of which have fueled a surge in retractions. According to Retraction Watch, the number of papers pulled from the scholarly record rose from about 1,600 in 2013 to more than 10,000 in 2023. More than 8,000 of those came from a single publisher, Hindawi, after investigations uncovered systematic misconduct. The scale was so damaging that parent company Wiley decided to retire the Hindawi name altogether.

Even journal metrics themselves are being policed more aggressively. In 2024, Clarivate suppressed the Impact Factors of 17 journals for excessive self-citation and citation stacking, up sharply from just four the year before. Beginning with the 2025 Journal Citation Reports, Clarivate will exclude all citations to and from retracted papers.

These actions point to a troubling truth: the same metrics we rely on to judge quality are also vulnerable to manipulation. And when manipulation becomes widespread, it not only undermines trust, it pushes the entire system toward a dangerous feedback loop. Retraction rates offer a stark illustration: in 2002, just one in every 5,000 published papers was retracted, but by 2023, that rate had surged tenfold, to one in every 500 papers.

From Survival to Prestige

The traditional mantra of “publish or perish” has not disappeared, but it has evolved into something more selective: publish for prestige. Research shows that the Journal Impact Factor (JIF) still plays a major role in academic evaluations, about 40% of universities in the U.S. and Canada explicitly reference it in promotion and tenure policies.

While the JIF remains dominant, other metrics now compete for attention: author-focused measures (e.g., the h-index), journal rankings (e.g., SCImago Journal Rank or SJR and Eigenfactor), and attention-based tools (e.g., Altmetric and PlumX Analytics). These can capture dimensions such as policy citations, media coverage, online engagement, or usage statistics. Such tools can broaden how we view research influence, but when treated as primary measures, they risk becoming yet another scoreboard, rewarding visibility over substance and inheriting the same distortions that plague the JIF.

This reliance on metrics influences research behavior in subtle but significant ways. Scientists may prioritize questions that are more likely to attract publication in high JIF journals, even when other topics could deliver greater societal or local benefit. Studies have documented that publication and career pressures are often “highly governed by pressures to publish in high-impact journals.” Work that is context-specific, interdisciplinary, or regionally relevant may be sidelined because it is unlikely to yield high citation counts, a concern highlighted by the Leiden Manifesto, which urges protecting “locally relevant research” that may otherwise be disadvantaged.

Over time, this dynamic narrows the diversity of scholarly inquiry, reducing opportunities for groundbreaking discoveries that fall outside the mainstream of global citation trends. This is consistent with Goodhart’s Law, which warns that when a measure becomes a target, it can distort the very processes it is meant to monitor. Recent comparative analyses of citation trajectories reinforce this dynamic. High-JIF journals tend to reward “fast uptake” themes such as artificial intelligence, the Metaverse, or other emerging technologies, while lower-JIF journals often excel with “slow burn” contributions in areas like racism, discourse analysis, or conceptual frameworks. These topics achieve significance more gradually, sometimes years after publication. This pattern illustrates Goodhart’s Law in real time: the more a metric becomes a target, the more it shapes what gets published, privileging rapid-visibility topics over those with enduring but delayed societal relevance.

The Hidden Costs of a Number-First Mindset

Metrics inevitably shape what is visible, and by extension, what is valued. A recent analysis of open-access journal coverage shows that among more than 62,000 open-access journals listed in the ROAD directory, only a fraction are indexed in major databases — just over 6,000 in Web of Science and around 7,300 in Scopus, while a more inclusive database like OpenAlex covers over 34,000.

This disparity means that many locally important or regionally focused journals remain hidden from global visibility. Algorithmic recommendation systems then exacerbate the issue, amplifying already well-cited, English-language research and pushing marginalized voices further into obscurity. The risk here is not merely academic invisibility, but the gradual erosion of a plural, inclusive research ecosystem.

Citation performance studies also show that most research articles follow a “slow burn” trajectory, gaining impact only in their second or third year. Yet academic evaluations rarely account for this time lag. Hiring and promotion committees often judge scholars on citation counts accrued within one- to two-year windows, penalizing precisely the kind of work that may take longer to gain recognition but ultimately delivers deeper, sustained impact. In other words, our systems of evaluation risk favoring the quick hit over the lasting contribution.

A Call to Rethink Assessment

Recognizing these structural issues has fueled reform movements, such as the San Francisco Declaration on Research Assessment (DORA), now endorsed by over 20,000 individuals and 2,000 organizations. The DORA’s central principle is straightforward: evaluate research on its own merits, not on the prestige of the journal in which it appears.

Some institutions have started making changes. University College London has revised its promotion criteria to move away from journal-based metrics, as outlined in its Academic Careers Framework (2018) and Responsible Use of Bibliometrics Policy (2020), which are highlighted in the European University Association case study report. These shifts are slow, but they show that the academic community is at least willing to question entrenched habits.

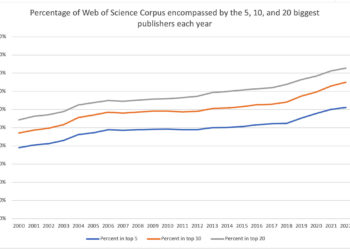

Similar reforms are unfolding globally. In China, new research policies have banned the use of JIF and other quantitative targets — commonly called “SCI-worship” — in hiring and funding decisions. In Latin America, regional platforms like SciELO and RedALyC emphasize inclusion and multilingual visibility as alternatives to global prestige hierarchies. Yet the underlying dynamics are complex: evaluation tools are embedded in a multimillion-dollar industry, with analytics suites like Digital Science’s Dimensions, Clarivate’s Web of Science and Journal Citation Reports, and Elsevier’s analytics ecosystem all anchoring the current system.

Emerging Predictive Alternatives

The growing realization that current metrics have limitations is prompting calls for change. But meaningful reform requires more than tweaking algorithms or adding alternative metrics. It demands a shift in how we define “value,” recognizing quality, relevance, and societal contribution alongside citation counts.

Some emerging tools attempt to move beyond blunt, retrospective measures, like the JIF. For example, the Article Citation Composite Index (ACCI), when paired with time-series models, can forecast how an article’s influence may evolve across three to five years. This shift from measurement to prediction highlights an appetite for more forward-looking assessment. However, even promising innovations such as ACCI come with caveats: without transparency, contextualization, and safeguards against misuse, predictive models could easily replicate the same distortions that have plagued earlier metrics.

We therefore need to follow several key steps:

- Increase transparency and accountability by sharing metric methodologies, clarifying data sources, and clearly stating limitations, a responsibility shared by publishers, funders, indexing services, and coordinated by global standard-setting bodies.

- Broaden definitions of impact to include policy influence, societal benefit, and regionally significant outcomes, ensuring evaluators and ranking bodies adopt multidimensional frameworks.

- Foster diverse and inclusive metrics that value contributions from all regions, disciplines, and languages, with academic societies and editorial boards leading by example.

At the Asian Council of Science Editors (ACSE), we believe metrics should serve integrity, inclusivity, and meaningful impact, always asking what we measure, why, and for whom.

Closing Thought

The Impact Factor arms race is not inevitable; it is a collective decision, reinforced every time we let a single number stand in for scholarly worth. Left unchecked, it rewards performance over purpose, and visibility over veracity. However, there is another way forward; metrics can serve a more constructive role as navigational aids rather than finish lines when transparency, context, and inclusivity guide their use. Valuing research for its substance, whether or not it fits the mold of citation-rich prestige, offers a path toward a system that rewards integrity, relevance, and long-term impact over mere numbers.

The future of research depends on whether we let numbers stay on the scoreboard or use them as the compass that points us toward integrity, inclusivity, and long-term impact.

Discussion

15 Thoughts on "When the Scoreboard Becomes the Game, It’s Time to Recalibrate Research Metrics"

Very thoughtful article. Thanks for writing and sharing!

Yes, “our systems of evaluation risk favoring the quick hit over the lasting contribution.” But let’s step back a bit. The recently deceased science historian, Mark B. Adams, documented that Boshevik idealism led in the 1920s to the beginning of “big science” – the turning of many palaces into research institutes. In evolutionary science (with which I am familiar) they began to parallel and even overtake, Western laboratories. Then, of course, came Stalin and ideals were quashed.

We are left with the Western capitalist democratic alternative, where scientists market their goods to so-called peer reviewers. As Winston Churchill is alleged to have remarked, the democratic system is bad, but it is the best we have. So, we have to make it work better.

Look around you today! Our hopes over decades were that the system is, albeit slowly, improving. But now, in the West, science is being bypassed in decision-making and Stalinesque authoritarianism is rising. Ms. Sayab’s fine piece might have mentioned this. We have to work at deeper fundamentals than those she has so elegantly raised.

Thank you, Donald, for sharing this rich historical perspective and for bringing in Mark B. Adams’ important work. You’re absolutely right that the dynamics we see today are part of longer cycles where political systems, ideology, and economics have always shaped how science is done and evaluated.

In this piece, I focused narrowly on metrics and their influence on research priorities, but I agree that deeper systemic factors, whether state control or market pressures, are inseparable from the conversation. Your reminder that we must situate today’s challenges in broader historical and political contexts is very valuable.

I hope future discussions can connect these layers more explicitly, as they all affect how we ensure research remains both rigorous and socially relevant.

The stark difference between where we were, and where we are now, regarding progress in scientific discovery, can be expressed in three percentages – 0, 20 and 100. As I see it, Maryam and I are concerned with improving the intertwined peer-review processes that underlying funding and publication. In my text Tomorrow’s Cures Today? (2000), I lamented the gap between a theoretical 100% and our present rate — deemed at 20%. Neither of us had anticipated the present crisis that threatens to take us to 0% and even into minus territory.

The essence of my perception can be outlined in the context of the thankful emergence of mRNA vaccines just in time to save lives in the pandemic. In a recent peer-reviewed publication (FASEB Journal, 2024), I note that authorities were obliged to grant only provisional approval of mRNA vaccines, because their primary originator, Katalin Kariko (now a Nobelist), had been trying in vain for decades to get peer-review approval of her fundamental studies (see her recent autobiography). Had she been successful, many unforeseen side-effects might have been avoided. This should signal the need for a major shake-up in peer-review processes.

Amazing post, it deserves to start a conversation!

Thanks so much, Michael! That’s exactly what I was hoping for, sparking a wider conversation on how we use (and sometimes misuse) metrics.

A timely reminder that research metrics should guide progress, not become the end goal themselves.

Absolutely, Muhammad, very well said. Metrics should be a compass, not the destination itself.

Ms Sayab and Mr Forsdyke’s comment both attest to the crisis of Trust occurring throughout the scholarly communications spheres. The layperson’s exposure to anti-science rhetoric is damaging how science is communicated with bad science reaching audiences it should not, and really great science battling for exposure behind paywalls and the scourge of the “Elitist” branding the rhetoric is slapping onto it. For we librarians in health, the matter of Trust™️when it comes to carefully curating evidence for use by healthcare professionals becomes a matter beyond that of integrity but perhaps even life, itself! Metrics only go so far as to engender this Trust in the evidence – it certainly helps, but it is by no means the only thing we rely on to ensure we are providing our cohorts with the best possible science, data and guidance-based-on-evidence. This is becoming critical mass now. The discussion around how to embed Truth, Integrity and Trust in science relies on journalistic standards that categorically supercede scholarly publishing’s increasing descent into mere capitalist greed/privilege.

Thank you, Michelle, for this powerful perspective. I couldn’t agree more, trust isn’t just an abstract value here, it directly affects lives, especially in health contexts. Metrics may play a role, but as you say, they can’t replace the deeper responsibility we share in how science is communicated, curated, and made accessible. What you said about truth and integrity going beyond numbers really hits home.

Yes, the DEI (diversity, equity and inclusion) of ideas, opinions and thoughts are more important right now than ever before.

What 3 years? Experts can quickly distinguish a breakthrough study from a mediocre one.

Thank you for taking the time to write and share such a thoughtful and insightful article. I truly appreciated the depth of your perspective and the clarity with which you presented your ideas. It offered a lot of valuable takeaways.

This article is good, thank you, yes you are right that metrics should act as a compass, not a finish line. If ACSE leads efforts to ensure inclusivity, integrity, and context-driven evaluation, it can help the research community move beyond a number-first mindset toward a system that values substance and long-term impact.

Totally agree Maryam and thanks for writing this very thought-provoking article. We created the Thomas Kuhn Foundation (https://thomaskuhnfoundation.org/) with this in mind: How can we set in motion a way to look beyond article metrics and assess the ‘real impact’ of research. Perhaps you’ve seen our initial case study, https://preprintwatch.com/? Here we use our KGX3 Engine to classify preprinted research according to the framework developed by Thomas Kuhn: is a piece of work “normal science” or a “paradigm shift”, Would love you feedback and further comments …

Gareth Dyke