Author’s note: The STM Research Integrity Day is conducted under Chatham House Rule, so some of what I have written below falls below my normal standards for citation and attribution.

I’m writing this post on my way home from the STM Innovation and Integrity Days, an annual program which this year consisted of five events (the STM Trends Brainstorm, Innovation Fair, Research Integrity Workshops, Karger Vesalius Innovation Awards, and the Research Integrity Day). Over the past few years, the program has grown into an extremely thorough and interesting discussion on the future of the STM publishing industry. There were far too many interesting things going on for me to summarize everything, so instead, here’s a few of my personal thoughts from the last few days.

There may be trouble ahead…

In recent years, research integrity has become an increasingly pressing issue. What a few years ago was a nagging worry in the back of a few people’s minds has started to look like a looming crisis. Without being alarmist, many publishers are reporting significant increases in submissions of questionable legitimacy and are increasingly investing in strengthening their process. Sometimes manuscripts contain faked or low-effort AI generated content (otherwise known as ‘ slop’). Sometimes they originate from papermills, or there are uncertainties in authorship or affiliation. Research integrity teams, and so-called sleuths are finding more and more cases of ethics violations including bad statistics, image, and data manipulation.

Unfortunately, it’s not easy to simply clamp down on poor behavior and bad actors. As James Butcher neatly summarized in a LinkedIn post, publishing has traditionally functioned on trust.

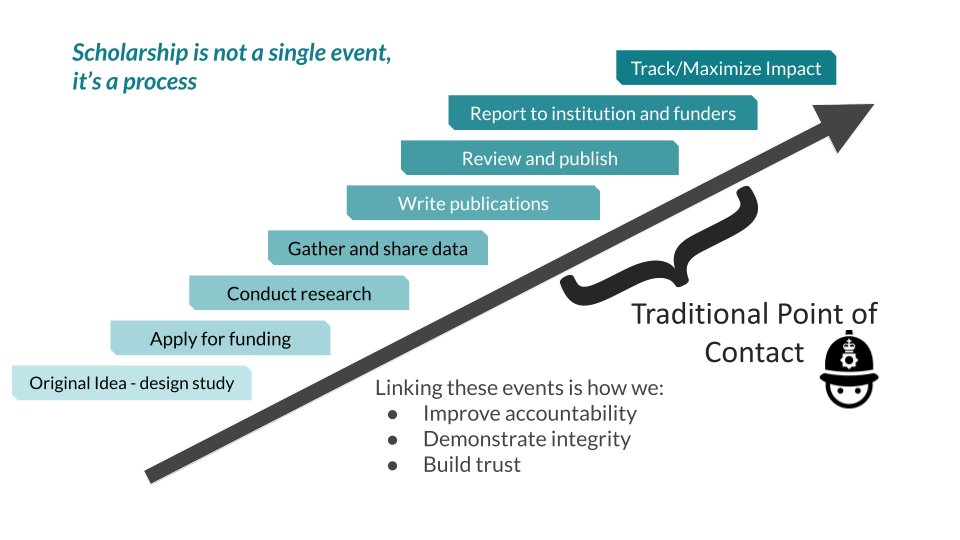

In the past, the trust layer was provided in large part by scholarly communities. Before the era of global research publishing at scale, learned societies largely worked at the national level and organized disciplinary communities around journals and conferences. These communities were a lot smaller than they are today and researchers often knew each other. Today, we live in a global research landscape of trans-disciplinary research that is increasingly problem-based, rather than disciplinary. As James points out, publishers are transferring that trust away from individuals and communities and towards systems.

To police or to assure

One big problem is the systems that we currently have aren’t robust enough for the level of quality assurance we need. When a publisher, institution, or funder receives a report of potential misconduct, they often find themselves without the evidence needed to draw a solid and reliable conclusion quickly. There are no agreed standards of evidence and investigators are reliant on the records kept by researchers themselves. With no consequences for not keeping good records, bad actors can often protect themselves from accountability.

There were some fantastic innovations pertaining to research integrity showcased this year. The Innovation Day and Vessalius Awards did a great job of highlighting some of the most interesting new ideas and startups. There were products that streamline peer-review and integrity checks, validate authors, affiliations, and citations, and many other valuable innovations. Some of the innovations target stages in the research process that publishers haven’t generally had much to do with in the past. For example, the winner of the Vesalius award, profectus academy, is a tool aimed at the currently undersupported task of grant writing.

So much of the current wave of innovation, however, is focused on supporting research integrity at the traditional point of contact for publishers.

In terms of assuring integrity, the challenge is that the scholarly supply chain begins a long way upstream of any event a publisher is involved with. It is impossible to study a manuscript and detect or intuit all of the activities that have led up to that single output and attempting to do so, can be a risky business.

Editors are being asked to take responsibility for the accuracy and rigor of research based on what the author chooses to share with them. When things go wrong and suspicions are raised post-publication, integrity teams can find themselves at risk of legal action or even the target of harassment. All of this is often happening in the absence of solid evidence one way or the other.

Hardening the supply chain

We need to move from an environment where publishers attempt to prove wrongdoing at the point of publication to one in which researchers are expected, and are able, to document the provenance of their data and the integrity of their research processes.

If we’re going to tackle this problem in full, we need to go upstream with serious intention. Publishers cannot do that alone. A major theme of the Integrity Day was the need for concerted collaboration between publishers, institutions, funders, and organizations that represent researchers, including learned societies, and groups like Quality Assessment and Reproducibility for Instruments & Images in Light Microscopy ( QUAREP-LiMi) and Open Science Clusters Action for Research & Society (OSCARS). Both of those organizations are working towards infrastructures to assert provenance and integrity in disciplines like microscopy.

The building blocks of an ecosystem where the scholarly supply chain is connected with rigorous provenance and integrity checks already partially exists. For example, the image certification standard of C2PA, could be implemented for imaging instruments as I described last year in my report funded by STM on the Feasibility of technical solutions for the detection of falsified images in research. Something like the NEXTCloud and OMERO server that QUAREP hosts could evolve into a sort of trusted research environment similar to those used in healthcare, pharma and engineering.

As always, the tech isn’t the hard part. Hardening the scholarly supply chain in a thorny socio-technical problem fraught with collective action problems, and hampered by years of historical mistrust and miscommunication. On the other hand, the tone of the STM Integrity Day gives me hope. In years gone by, the various stakeholders in our ecosystem have pointed to each other when scandals and problems emerged but now perhaps the time is right to forge a new alliance between publishers, funders, institutions and researchers to protect the integrity of the scholarly record, before it’s too late.

Discussion

4 Thoughts on "Why We Must Work Together to Harden the Scholarly Supply Chain"

Thank you for this piece, Phill. Timely and critical. If anyone would like to know more about United2Act Against Paper Mills, a coalition of research institutions, publishers, investigative researchers, universities, and publishing infrastructure leaders, please be in touch. Nandita Quaderi and I, as co-chairs, are eager to connect with anyone interested in a briefing on our work. We can also put you in touch with our working group leads for Education, Stakeholder Engagement, and Funder Outreach as appropriate (https://united2act.org/working-groups/).

Spot on.

The publisher supply chain is unusual in that most of the participants are unpaid, anonymous volunteers. So, process change is more challenging to implement than with paid staff.

Phill, do you think that the tools you describe will significantly alleviate the workload on the volunteer community, or will publishers turn to paid “peer” evaluation using commercial vendors to reduce the volunteer workload?

Hi Richard,

When I write about the scholarly supply chain, I’m not just referring to peer-review. The traditional points of contact that publishers have with research is towards the end of a chain that begins in labs and in offices in research institutions. There is a diverse range of people involved in it. There’s the principal investigators that lead and manage the research groups, technicians, students, post-docs and sometimes junior faculty that have a variety of roles from taking data to conducting their own research programmes. Those researchers are supported by librarians, infomaticians, data managers, research managers, and a whole host of professional services staff. Increasingly, third part services are being used like contract research organisations, graphic designers, language editors, and so on.

When manuscripts finally make it to an editorial office, another group of people get involved. There are the editors (some of which are paid, others are volunteers), and the peer-reviewers, who are unpaid, but there’s also editorial assistants, managing editors, and the research integrity teams to name but a few.

I don’t think it’s accurate to say most of those people involved are unpaid volunteers.

On the publishing side, editorial offices increasingly handle a barrage of integrity checks and many publishers have research integrity teams who go to heroic lengths to investigate fraud with the signals and evidence they have to hand. Having tools and systems for research quality and provenance assurance will make the jobs of research integrity teams more tractable and reduce reputational risk.

As for peer-reviewers, nothing much would change. Reviewers cannot detect research fraud, they just don’t have the evidence to investigate, they never did have the time and it was never their job. That’s why the system has always relied on trusting that researchers were basically honest when writing manuscripts. The only ways that the workload will be reduced is either by reducing the number of manuscripts that get reviewed, or increasing the pool of reviewers.