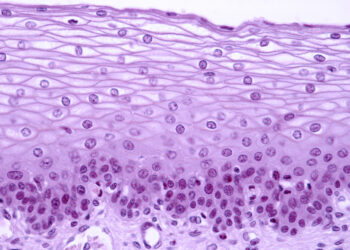

- Image via Wikipedia

Do we want to commercialize access to knowledge?

— Robert Darnton, The Library: Three Jeremiads

As we enter a new age, maybe art will be free. Who says art has to cost money? And therefore, who says artists have to make money?

— Francis Ford Coppola, interviewed in The 99%

(For purposes of this posting, I’m going to use the words “information” and “knowledge” more or less interchangeably — not because information and knowledge are the same thing, but because sharing information is functionally the only way to transfer knowledge.)

In an earlier posting, I took Robert Darnton to task over what I felt to be substantive problems with his “Three Jeremiads” essay. In that posting I made passing reference to Darnton’s question about “commercializ[ing] access to knowledge,” and said that it raised an issue worth discussing in a separate posting. Since then, I also came across a fascinating interview with legendary filmmaker Francis Ford Coppola, a quote from which is also cited above to help set the stage for this piece.

We could argue all day about whether art is just a subset of information, but we can probably all agree that art and information share at least one very important characteristic: both exist only as the result of an investment of labor. Artists and writers take raw materials (words, musical tones, data, paint, etc.) and invest time, energy, and intellectual expertise in the work of turning those materials from formless abstraction into objects or statements that convey a set of meanings.

This is the only way that either art or information can come into existence, which in turn means that there’s no such thing as “free information.” You or I may not pay for the information we use, but that doesn’t mean it’s “free” – it just means that the cost of creating the information and getting it to us has been borne by someone else.

In the face of this reality, both Darnton and Coppola ask the same question in different ways. However, Coppola’s version is arguably more intellectually honest, because it acknowledges the connection between “costing money” and “getting paid for one’s work.” If he had stopped with his second sentence (“Who says art has to cost money?”), the obvious answer would have been “the artists who work to create it.” And he acknowledges that obvious response later in the interview, suggesting that filmmakers might do better to give up the idea of making their living as filmmakers and instead get other jobs, making movies in their spare time as a labor of love and giving others access to their art at no charge. Young filmmakers might resent such advice from someone who has already made his fortune as a filmmaker, but at least it recognizes a fundamental reality of information economics.

By contrast, when Dr. Darnton asks whether “access to knowledge” should be “commercialized” he implies that access to knowledge is possible without commercial considerations entering the equation. And he’s right, in a way — all of us exchange knowledge all the time without any expectation of commercial gain. But that’s not the kind of knowledge exchange he’s discussing in the essay from which the above quote was taken; that essay is about access to scholarly products generally, and to the commercially published books included in the Google Books corpus in particular.

The fact is that there is no such thing as free access to the knowledge containers he’s discussing; there is only the question of who will pay. That was true of this particular fund of knowledge long before Google entered the picture.

Even in the nonprofit sector, information workers generally expect to be paid for their labor. Amateur writers, musicians, and artists may work simply for the love of their art and distribute their work to others at no charge – and people like this do indeed make up a pretty large percentage of the world’s writers, musicians, and artists. But the artistic and intellectual product of dedicated amateurs with unrelated day jobs comprises a relatively small share of the knowledge to which scholars and researchers need access. If we want access to knowledge produced by professional knowledge-creators, then access to it will have to involve a significant element of “commercialization” in that someone will have to pay the creator; someone will have to absorb the cost of preparing the product for distribution; and someone will have to absorb the cost of distribution.

When Darnton asks whether we should “commercialize access to knowledge,” I suspect that what he’s really asking is whether access to knowledge ought to involve costs to the end-user. I suspect also that what he really objects to is not cost itself, but obvious and direct costs (such as end-user fees or subscription charges) as opposed to hidden and indirect costs (such as taxes, tuition, student fees, etc.). This is not a dishonorable position; as I pointed out in my earlier post, hidden and indirect charges are a perfectly reasonable way of covering the costs of some things. But they are not innocent of commerce or of marketplace competition. Those, like me, who work in the public sector creating intellectual products that others can use at no charge (like this posting, for what it’s worth), compete for our jobs with others who want them; are retained at significant cost by our employers, who compete to retain us if others vie for our services; are evaluated based on the quality and utility of our outputs; are compared with competitors at other institutions; are required to produce those deliverables that are demanded by our clients and stakeholders. University press monographs cost money; so do journals from nonprofit societies. A commercial exchange may take place in the nonprofit sector, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t commercial.

Ultimately, what matters to readers, scholars, researchers, and other users of information products is not whether or not information transactions are “commercial.” What matters is whether information is a) available, b) accessible, and c) affordable. “Free” (i.e., paid for by someone else) lies at one end of the affordability spectrum, and all of us welcome that price when we can get it. However, we tend to like it less when it’s the price offered for our own work. To eliminate “commercialization” from the knowledge economy would mean, necessarily, to reduce drastically the amount of information that will be created – because it would mean, by definition, that only amateurs will create information.

Does that really sound like the recipe for a better information future?

Discussion

20 Thoughts on "Darnton, Coppola, and the Impossibility of Free Information"

This is the only way that either art or information can come into existence, which in turn means that there’s no such thing as “free information.” You or I may not pay for the information we use, but that doesn’t mean it’s “free” – it just means that the cost of creating the information and getting it to us has been borne by someone else. —

However, if the payment was done by publicly funded institutions that means that the money invested in art/education/culture is coming back to *us* in the form of free artistic/educating/culturology materials.

I think what people find problematic is the notion that publishers/creators/whatever you want to call them make money that is far in excess of the costs of creating the information – which is certainly the case in the scholarly journals arena.

It is also true in the case of university professors who are paid salaries far in excess of the costs of creating their information. Shall we start slashing researcher salaries to the bare minimum?

Also it should be noted that many scholarly publishers are not-for-profit, often scholarly societies or institutions themselves, and those excess profits are immediately reinvested in the generation of more information.

One of the strongest arguments for Open Access is that the cost of publication (typically a few thousand dollars) is dwarfed by the cost of the research (often hundreds of thousands of dollars). In that sense the money made is nowhere near the cost of creating the information.

Moreover, I am no fan of the big commercial publishers, but I don’t see the money they make as being “far in excess of the costs” of creation. A 30% profit margin would not be cited as evidence of larceny in most industries, including those that supply and spring from academia.

Maybe not larceny, but that profit margin is certainly up there. Here is a table of profit margins by industry: http://biz.yahoo.com/p/sum_qpmd.html

The top three are Closed-End Fund investments. The top profit margin for an industry that actually makes something? Periodical publishing, at 33.5%. Next highest is drug manufacturing at 23.10%.

That’s a very good point.

Note, however, that books are down at <9%, and among academic publishers these are often subsidized by journal operations.

I don’t believe that what you’re pointing at is the profit margin of the businesses involved, but the profit margin of investing in the stocks of these businesses. That’s a completely different thing.

No, you are incorrect: http://beginnersinvest.about.com/od/incomestatementanalysis/a/net-profit-margin.htm

The other columns in this table are concerned with investments, but the net profit margin column is derived from revenue, not investing. It’s an important data point for investors, which is why it’s in that table.

Well, then explain how this gets to a net profit margin of 33.50% based on the following margins: 11.81, 11.52, 7.46, 5.46, -2.80, -10.09, -17.28, -34.12, -44.20, -85.56, -85.56, -150.69, -199.23, NA, NA, NA, NA? I can’t make sense of it either way if the 33.50% is supposed to represent the most recent quarter average. If these were an industry’s profit margins recently, what would I make of this?

Also, just because these are periodicals doesn’t mean they’re comparable. Martha Stewart is in here along with Elsevier, for example.

Considering that Elsevier represents several of the NA listings here, I don’t think this gives much of an accurate portrait of scholarly publishing.

How is the industry’s profit margin as a whole determined? I don’t see a link to their methodology for the group, rather than the individual company link that you provided. Does one highly profitable corporation skew the findings for many small-margin university presses?

I’m wondering what you mean by “small-margin” university presses? All but a handful of the largest presses operate with subsidies from their parent universities, and without those subsidies they would all be negative-margin enterprises.

Excellent post, Rick.

There are several competing views of information-as-property, each based on different assumptions, values, and reward systems:

- Labor theory recognizes and rewards individuals for their hard work.

- Utility theory (or utilitarianism) attempts to maximize net social welfare.

- Personality theory acknowledges that creation is a form of self-expression and selfhood.

- Social Planning theory views intellectual property as a good that can be used to build a just and attractive culture.

You make a compelling argument for the Labor view, and that creators should be rewarded for their original contributions. Darnton appears to be grounded in Utility theory and Social Planning Theory.

Both of you are correct. It just depends on how you view and value information and those who create it.

Hi, Philip —

Actually, my posting doesn’t intentionally address the question of information as property at all — though obviously it’s a very interesting question. What I’m trying to focus on is the question of cost, and the (to me, inevitable) connection between cost and commercial considerations. Reasonable people can disagree about what kind of property a document represents, or whether it should be considered anyone’s “property” at all. But when that argument ends, the costs will still be there, and someone will absorb them. The distribution of those costs will be settled by a process that can only, I think, meaningfully be called “commercial,” unless the original creator decides simply to absorb them himself (in which case there’s no process). I’m not really making a “should” argument here — original creators go without pay all the time — except that when it comes to access to knowledge products, I don’t think we should demonize the idea of “commercial” in order to privilege the spurious idea of “free.”

Certainly, non-profit publishers have to operate as “commercial” enterprises in the same marketplace as their for-profit peers if they are to remain in business, unless they are fully subsidized (as, say, the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy is striving to do by creating a permanent endowment). The question that arises for me, at this point in the development of scholarly communication, is whether the “costs” of maintaining a market-based system for the creation and distribution of information/knowledge are any longer providing us with the most efficient system, compared with the alternatives like open access. The expense, for example, of publishing a monograph in 400 copies is considerable, and yet the potential impact is very limited because of the very low number of books available to potential readers. I think it’s time we explored alternative ways–as I suggested in my Charleston talk–for funding the creation and publishing of scholarly books that bypasses the cumbersome mechanism of print distribution and allows anyone with an internet connection to benefit from the knowledge produced. We are spending way too much money now to support a system that has outlived its usefulness.

You are right to question whether the distribution system has outlived its usefulness, but I am not sure that example is valid.

One prints 400 copies of a monograph precisely because its readership is limited. If the potential readership were higher, one would print more copies. Online, the costs of printing are eliminated, but there are nonetheless considerable costs, which must somehow be recouped.

The problem with scholarly books is that most are for scholars and almost by definition have a limited potential readership. Online the economic pressure switches to questions of whether the limited page views justify the per-monograph expenditure.

The solution to this problem in OA journals is to gain economies of scale and increase revenue by increasing the total number of articles published. The worry for OA monographs would be that such a solution either is unachievable because there isn’t the volume or mutates into an academic-vanity-publishing enterprise that ultimately costs the system more.

Hi, Richard —

This is going to seem like a minor quibble, but I think it’s actually important. You said:

“One prints 400 copies of a monograph precisely because its readership is limited. If the potential readership were higher, one would print more copies.”

But since we’re talking about information economics, I think it’s important to distinguish between “potential readers” and “likely buyers.” A UP prints only 400 copies of a book because it expects to sell only 400 copies, not because it thinks only 400 people would read the book if it were broadly available. I think this goes to Sandy’s point about efficiencies and OA: I’m agnostic about OA as a sustainable economic model, but one thing it has the potential to do very, very well is maximize efficiency of access.

So I guess all I’m saying is this: the fact that there are 4000 likely (let alone “potential”) readers for a monograph doesn’t necessarily say anything about the number of physical copies that should be printed. That number can only be determined by the number of likely buyers.

I agree with Rick’s point, distinguishing buyers from potential readers. It’s not as though the content in these monographs is so esoteric (as might be the case with some STM journal articles) as to be inaccessible or uninteresting to a larger number of readers. It is rather that the presses believe they can sell the book at $75 only to libraries and so print accordingly. The content, however, might be used by teachers in graduate courses and upper-level undergraduate courses much more broadly if it were available at no charge to the user, not to mention scholars in many other countries who will never see the book at all if it exists only in the collections of a handful of U.S. libraries. So, yes, I am talking about efficiencies in use as well as in production and distribution.

I take the point. But for most scholarly works, I think it is naive to think there is a vast potential (but currently unserved) readership out there – even authors would feel that is wishful thinking.

For the most part we are talking about extremely niche material aimed at a very rarefied academic audience, the majority of whom will either be in the institutions that purchase a copy of the book or easily able to afford purchasing a copy – I guess what I’m saying is that in this case the buyer equates (approximately) to the readership.

Where this is not the case, the work tends to be published not by a scholarly press but by a trade publisher with a bigger print run.

The fact that photocopying–and, more recently, copying for e-reserves and course-management systems, which brought about the suit against Georgia State–shows that there is a great deal wider potential market in the academy than was being reached by those who actually could afford to buy the books. Surveys I did at Penn State, before we ceased publishing in literary criticism,revealed there to be a significant market for the content beyond those willing to pay the often steep prices that are charged for monographs.