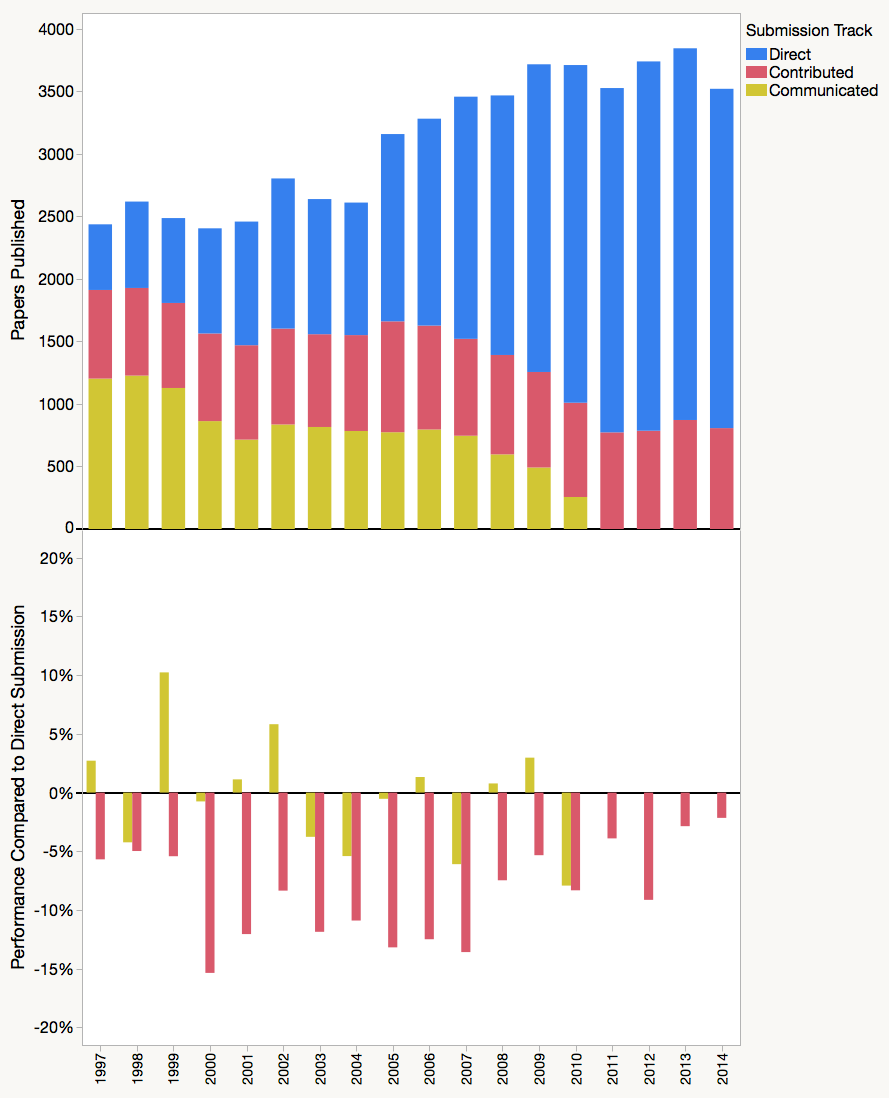

After years of slowly tightening its editorial policy, papers contributed by National Academy of Science (NAS) members appear to be performing more like other submissions.

PNAS currently allows authors to submit through two tracks: Direct, in which papers are subject to the normal rigors of single-blind peer review, and Contributed, in which a NAS member may secure their own reviews and submit them alongside their paper. A third track (Communicated, in which authors submit manuscripts through a NAS member) was abolished in 2010. While Direct submission is the normal route for most scientific journals, it is relatively new for PNAS, which adopted it in 1995. Today, direct submission account for nearly 80% of all published PNAS papers.

Providing NAS members certain publication privileges is a controversial topic. While some argue that highly-esteemed scientists should have mechanisms to publish their work quickly (especially unconventional papers), others believe that such privileges come with the risk of abuse. NAS members may use the Contributed track to sidetrack adequate peer review or use it as a dumping ground for papers that cannot be published elsewhere. Reporting for Nature, Peter Aldhous revealed that while the majority of NAS members used the Contributed track rarely, there was a small group of members who used the track very frequently.

A 2009 citation study of PNAS papers by submission track reported that Contributed papers received 10% fewer citations, on average, compared to Direct submissions. The top 10% of Contributed papers, however, outperformed the top 10% of Direct submissions, suggesting that the Contributed track may facilitate the submission of time-sensitive groundbreaking work. The analysis, however, was limited to papers published mid-2004 through mid-2005, leading one to wonder whether the effect was still in play. Over the years, PNAS has enacted successive editorial policies to place limits, restrictions, and other qualifications on the publication privileges of NAS members. PNAS hired me last year to study the performance of papers by submission track and gave me permission to report the findings.

In each year of publication between 1997 through 2014, Contributed papers consistently underperformed against Direct submissions, receiving 9% fewer citations, on average, controlling for the paper’s topic and publication date. The effect was greatest for Social Sciences papers (12% fewer citations). Nonetheless, the effect has attenuated over the past decade, from 13.6% fewer citations in 2005 to just 2.2% fewer citations in 2014 (see Figure below).

Moreover, the top 10% of Contributed papers outperformed the top 10% of Direct submission, but at the bottom end, Contributed papers were more likely to remain uncited after their first two years of publication. Consistent with our main findings, both of these effects have also been attenuating over the past decade and were not detectable in the last five years of publication. In a related study of academy-track publishing in mBio for fellows of the American Academy of Microbiology I recently reported that there was no discernible performance difference between submission tracks.

Both of these studies suffer the limitation of being unable to completely disambiguate author effects from submission track effects. While we know that all Contributed papers were authored by at least one NAS member, we do not know the author status of Direct submissions. Some NAS members may be leery of what signal the Contributed track conveys to readers (the submission track is listed on the front page of each article), and avoid the stigma by submitting all manuscripts through the Direct track. Other NAS members may select the submission track based on the paper.

Whatever the cause(s) that created a performance difference between the Contributed and Direct track, it appears to have largely disappeared, likely the result of tightening editorial policies.

A full description of the citation analysis, “Comparing the Citation Performance of PNAS Papers by Submission Track” is available from the bioRxiv.

Discussion

5 Thoughts on "PNAS: Tighter Editorial Policy Improves NAS Papers"

Phil, your measure of performance is a bit too narrow for me. Performance of scientific papers is mostly about how often and in what ways the papers are used by other researchers to stimulate research in new or existing areas. The papers may never be cited but still provide this guidance. Climate science is a good example here. Much of the research over the last 20 years in this area has been inspired by other research, sometimes published, sometimes not. These inspirational papers are often not cited. But still are inspirational.

Ken, Do you have any metrics to suggest (existing or not, direct or indirect) that would pick up “inspiration”? I know just what you mean: sometimes I’m reading an article (and not usually a scholarly article, I’ll admit) and I think “hey, that idea could be applied over here too…”. **

I imagine many of us who work in “impact assessment” recognize that citations are only part of the story. Many clinical (or practitioner) journals have talked about this for years, and it is probably what gave rise to the “Journal Usage Factor” work a few years back (to create a usage-based metric that could stand alongside the Journal Impact Factor, to add some dimensionality beyond citations). Social media is another dimension that might capture inspiration (along with a lot of other things).

So what signals do this kind of “inspiration” leave behind that we might be able to pick up, refine, etc.?

** In some citation analysis work we are doing, we are looking at tracking what I call “left field citations”. E.g., citations to a work from journals well outside the “usual suspects”. But this is still citation-based.

I do a lot of interviewing of young scientists regarding the people and events that lead them to become a scientist. I also work through lots of “what-ifs” with established scientists to help them and me understand better how they viewed the world earlier and later in their careers, including the work of scientists. I don;t get detailed bibliographies from this work. But I do gain a wide angle view of the roads taken and not taken and the reasons for the choices made. The word inspiration is used quite often by the interviewees.

Citation-based measures are not perfect measures of anything – not even perfect measures of “citation” (since not even Google Scholar captures “everything” that could reference a work).

But before you throw the citations out with the bathwater: a citation is a highly specific point-to-point link between two (published) works; it is (most often) created by an expert in the field for the purpose of indicating some type of meaningful relationship between those works. Any given citation can be positive, negative or neutral (mere acknowledgement of the canon), but, when you can look at 80 million of them in a year – it’s a LOT of good information.

When there is need, you can also dig-into the details of a given paper’s in-coming our out-going citations – you can analyze (as Phil often does) their patterns and “flow” at the level of the paper, the person, the field, the institution, the journal (not just JIF – SNIP, SJR, Eigenfactor, etc).

Use them well, or use them poorly, citation metrics are based on a network of interactions created by the scholarly community in the process of publishing their work.