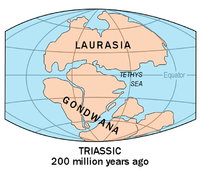

My high school geography teacher drove an old car with a bumper sticker that read, “Stop Continental Drift!”

The humor in this slogan lies in its futility. Plate tectonics are a part of the inevitable changes in our earth and, while not formally recognized in science until the 1960s, continued without the support (or protest) of advocates. Plates move, the earth evolves, and there’s nothing we can do about it except recognize and accept the inevitable.

The antithesis of evolution is revolution. Revolution assumes people have the power to change things and chart their own destiny.

In her two-volume book, “The printing press as an agent of change,” Elizabeth Eisenstein views the invention of the printing press in the 15th century as starting a revolution over how we relate to text and setting the stage for the Reformation and scientific revolution. Her position, while fleshed out in great historical detail, did not go unchallenged. In what appears to be a slug-match between two historians in The American Historical Review, Adrian Johns challenges the notion that machines change how people behave in favor of a view that society was simply ready for the printing press. In other words, evolution, not revolution.

Let’s fast-forward through five centuries and view digital text and the Internet through the same two lenses. Through the revolutionary lens, open access is a movement started by scientists and librarians who see their purpose as wresting control of scholarly communication away from those who control the publication process and returning it to the people. The NIH Public Access Policy and self-archiving mandates, most notably Harvard’s and now MIT’s, can be seen as the result of collective public action to right historical inequalities and empower the oppressed. It’s about the rights of taxpayers, mothers with sick children, and the poor in developing countries. Revolutions don’t get any better than this.

Information does not want to be free, it needs to be free in order for it to become part of science.

And yet science has always been about making things public. In order for new discoveries to become part of the scientific discourse, they must be made public and open to scrutiny and verification. And the more public the better, which is why high-circulation print journals were considered the most prestigious places to publish. Information does not want to be free, it needs to be free in order for it to become part of science.

declaring victory over the inevitable is a bit like cheering on continental drift

Informal communication in science reaffirms this point. Scientists share manuscripts and working papers, travel to conferences, give invited talks, and talk to the press (when asked). Sharing of information is an ethos of science, because science is, at heart, a public endeavor. Through this lens, the fax, photocopier, email, and the arXiv did what scientists wanted them to do — help share their discoveries.

Through this evolutionary lens, scholars were ready and willing to use new tools to help disseminate their scientific discoveries. In the same light, federal and institutional mandates to improve access are simply the bureaucratization of the inevitable, and declaring victory over the inevitable is a bit like cheering on continental drift.

Discussion

2 Thoughts on "Access: Revolution or Evolution?"

Phil, Your last paragraph here is clever and challenging. If open access is evolutionary and inevitable then I am for this path, but I am also for mandates for two reasons:

1 To speed the process up.

2 To balance the existing bureaucracy of publication and scholarly communication, simply, shifting the balance of debate.

It may feel like we are progressing at geological speed, but these are human and cultural issues and we can affect them.

Steve Hitchcock

Thank you for the link to the Johns article. His book “The Nature of the Book” has been on my shelf for a while, now. This tells me that it’s time to finally read it.

And I agree think that the revolution/evolution construct is a useful way of thinking about scientific communication.

I will be interested to see what may lie around the bend for scientific communication, given its current potential to play out as the story “The Little Red Hen” — but without the happy ending.

Obviously, openness is imperative for innovation; and profit need not be part of the scientific discovery equation. But the necessity of openness to the furthering of scientific knowledge; and the ability to profit from one’s intellectual property, remain unharmonized. Perhaps this, too, will eventually come to follow a specific ‘evolutionary path’ toward some form of reconciliation.

Makes one wonder exactly what kind of pressure might drive such a development. If indeed it ever moves out of its current realm of contentiousness.