The pattern is familiar.

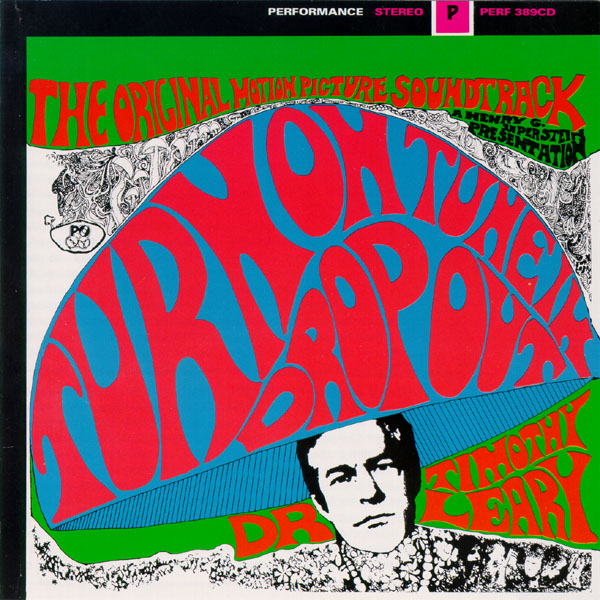

Start a blog, edit a page on Wikipedia, submit a video to YouTube, or recommend an article to Digg. What starts as an enthusiasm to participate in the great global production of information most often ends with apathy. Turn on, tune in, drop out.

Yet a few contributors become wildly successful. One blog post turns into a regular gig with a following of dedicated readers. A wiki editor becomes an administrator. An amateur video artist creates a fan base and begins a professional career.

Much of what determines the fate of those who become successful and those who will drop out is early feedback in their careers, according to three researchers at the HP Social Computing Lab in Palo Alto, California.

Their article, “Feedback loops of attention in peer production“ by Fang Wu, Dennis Wilkinson, and Bernardo Huberman was posted on May 12th and is freely available in the arXiv.

By analyzing 2.7 million stories submitted to Digg and nearly 10 million videos uploaded to YouTube, the researchers were able to discover some general trends on who stays in and who drops out.

First, dropping out is strongly predicted by a lack of attention. Since these sites provide public statistics (video views or Digg numbers), it becomes clear who is getting the attention and who is being ignored.

Conversely, popularity is strongly associated with productivity. The more attention you create, the more likely you are to contribute. And the more you contribute, the more likely you are to build a fan base who track your future submissions. A feedback loop thus motivates the successful and discourages the rest. Moreover, persistence doesn’t seem pay as a long-term strategy, according to an earlier study of YouTube behavior by Wu and Huberman.

Understanding behavioral models that allow a select few individuals to become wildly successful seems to explain a lot about economies in which individuals are rewarded not with fortune, but with fame.

On the surface, this may seem a lot like scholarly publishing. Authors gift their manuscripts to a publisher and are rewarded with intangible forms of peer-recognition like citations, downloads, and if they’re lucky, prestigious awards.

But scholarly publishing has something that YouTube and both Digg lack — the brand name of a journal. The journal name sets an expectation of quality to the reader and thus an immediate form of attention. Get an article published in a top-tier journal and you are likely to be read (and cited) much more frequently than if your article were published in a second-tier journal. This explains why scientists compete so fiercely to have their work accepted in a brand name journal, while a long tail of little-known journals starve for manuscript submissions.

Journals are channels of attention in a cacophony of noise. A reader needs to do little more than tune in and find the right channel. There is no need to turn off or drop out.

Discussion

1 Thought on "Successful Crowdsourcing Requires Feedback"

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=cb7b5ec1-a2c9-4fac-86fc-d6136218808c)