One afternoon in the men’s shower room of a Cornell pool, I was at the receiving end of a long rant by a researcher whose manuscript was rejected by a prominent journal in his field.

“The editor is getting too old. He should retire!” was one declaration. “The reviewer didn’t understand the science!” was another. And, chalking it up to petty rivalry: “I’m sure one of the reviewers rejected my paper because he knew it came from my lab. I’ll never submit to this journal again,” he concluded, “It was a waste of time.”

At one point, I offered up the possibility that perhaps the manuscript wasn’t his lab’s best work. And, if indeed, the first journal missed a great manuscript, there must be several other journal editors who would would love to see it. Unfortunately, this just led to another rant about the problems in journal publishing, why the system is completely broken, and how it needs to be fixed.

Many readers of this blog have been privy to interactions like this. Editors attempt to make the best possible decisions with never enough information. And yet, with a limited group of experts, each of whom may harbor deep biases of their own, we have something that works. Still, it could be better.

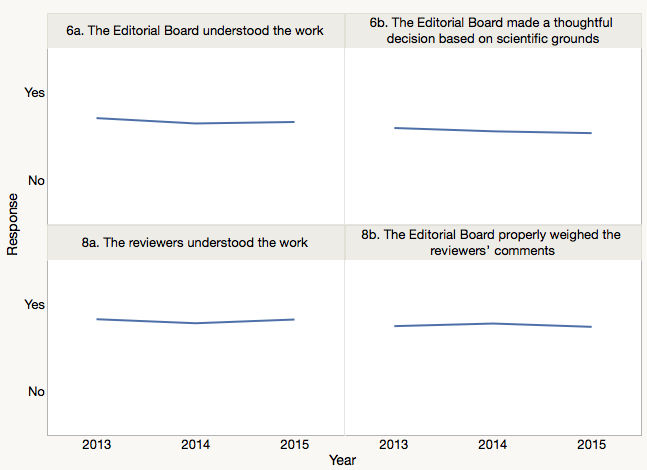

I worked recently with a medical journal publisher that wanted to improve the author experience. For the last three years, this publisher has been surveying their corresponding authors–those whose manuscripts were rejected as well as accepted–to understand how they could improve the submission, review, and publication process. The publisher had made some editorial policy changes over the past year–most importantly to restrict the number of additional experimentation and revisions required of its authors–and wanted to know if these changes made any difference to the author experience. As you can see in the first Figure, it doesn’t look like their policy changes made much of a difference.

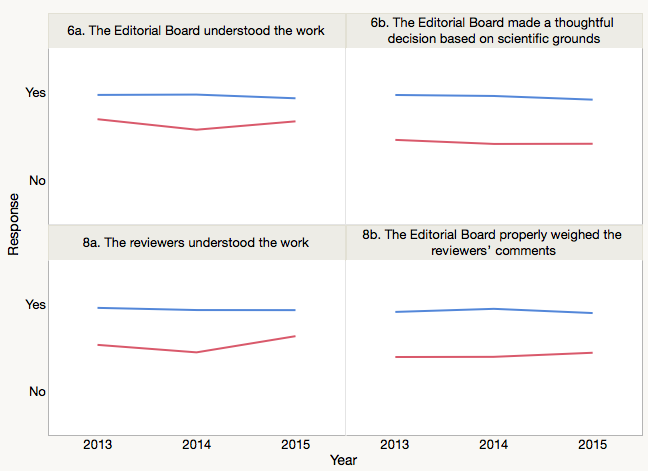

Break the respondents down into authors whose manuscript was accepted (blue) and rejected (red) and you’ll notice a great schism in author responses (Figure 2). Not only did rejected authors believe that the editorial board failed to understand their work, but peer reviewers — supposed experts in their field — failed to understand it as well. In the minds of rejected authors, the editorial board did not properly weigh the reviewers’ comments and ultimately made decisions that were not based on scientific grounds. Not surprisingly, rejected authors were much less likely to believe they would ever submit again to this journal. In contrast, accepted authors were resoundingly supportive of nearly every aspect of the journal.

What does this survey tell us about the perception of authors?

First, I think it indicates that the perceived competency of editorial boards and their ability to objectively and scientifically evaluate the quality of a manuscript is largely determined by a single accept/reject decision. While corresponding authors should act as partisan supporters of their own work, a perception of unfairness in the editorial and review process weighs heavily on their overall experience. Second, it confirms that the notion of “scientifically sound” isn’t a quality that can be evaluated objectively with a yes/no decision, but is something that is highly subjective and contextual.

For journals that wish to be selective in what they publish, rejection is just part of the process. Unfortunately, many journals send out form letters to rejected authors, conveying a sense that their papers may not be worth the time it takes to write an original correspondence. The rejection rate of the journal is often stated in these form letters, implying that publication is more of a lottery than the result of careful selection.

In addition, some editors do a poor job editing reviews to ensure that they are written politely and contain constructive remarks. Dismissive, sarcastic, and sexist remarks can often make it back to authors when they are at their most sensitive and emotionally vulnerable. At its worst, a single remark can create a major public relations disaster for a publisher.

I don’t know whether this Cornell researcher would have reacted any differently had his rejection been communicated any other way. Would addressing the emotional state of the rejected author help in any way (“I know you may be feeling very angry and frustrated by our decision”), or merely prime authors to feel that outrage is the normal response to rejection? Does offering a consolation prize (“We’d be happy to consider your manuscript for publication in another [viz. lower-prestige] journal we publish”) help with rejection, or just rub salt into the wound? And lastly, is it worth the time to write individual rejection letters, or does it simply invoke authors to write appeals?

While I don’t have a remedy for healing the emotional harm that can be done in the rejection process (other than ensuring that rejected authors are treated with respect and insulated from insensitive comments from reviewers), I don’t believe this topic has received sufficient attention when discussing the experience of authors. All of the surveys I’ve seen have been limited to the experiences of accepted and published authors–a response set that may be just as equally clouded and biased.

Discussion

13 Thoughts on "Extreme Bias: How Rejection Clouds The Eyes of Researchers"

One of the conclusions of our (CIBER) work on Trust in Information Sources was the centrality of peer review and the general trust in the way it works BUT in the free comments section of our international questionnaire there were some rants equivalent to shower-room experience of Phil.

The word “corruption” was frequently used in these rants and sometimes it was linked to the concept of old white males holding down younger, black, females to keep control. There is an excellent social sciences blog which gives house room to such effusions – nothing quantified you understand. I agree entirely with the last paragraph. I do wish publishers would work harder on the user interface.

Anthony

Phil, this is fascinating stuff. For those of us that have worked in editorial offices for a long time, we all have bruising stories of being subjected to invective from disgruntled (rejected) authors.

I am sure it is well beyond the scope of the study you undertook for the publisher, but an interesting follow up to your study would be to independently verify the reviews the authors received to then determine if the unhappy authors truly had a point. That would presumably tell us a lot about the quality of peer review and its role in agitating the authors. In addition to everything you noted, such as communication, I think it also important in any study of author satisfaction to account for the perceived quality/ranking of the journal. Working at a mid-tier journal, I know many papers have cascaded down to us and once we reject that very same paper the authors simply hit the next journal on their target list. They really are not that invested in us enough to care.

I would say the most important change I have implemented to the entire peer review process at my journal is the appointment of a specialist reviewer to monitor methodological and reporting issues. This reviewer, who is skilled in statistical and methodological issues, not the subject matter, provides well reasoned reviews that can often be decisive in determine the outcome of peer review. Stripped of any bias a subject expert may have, these reviews have typically added clarity to situations where authors were less than impressed with our decision to reject their paper.

When at ACS they rejected about 90% of papers submitted but of course their journals have among the highest of impact factors. I think it would help a great deal if every professor did a one month stint as a publisher’s sales rep, they would learn a lot about rejection which is just a part of life.

It is unclear to me how this survey “confirms that the notion of “scientifically sound” isn’t a quality that can be evaluated objectively with a yes/no decision, but is something that is highly subjective and contextual.” What is the connection? I realize that “sound science” has become a political term of art but surely there is such a thing.

gargh!

If an editor/reviewer/board doesn’t understand the science or the paper (or doesn’t read it – I have proof this happens a lot), or doesn’t WANT to understand it, rejection is more likely.

Your figures show the expected consequence. Nothing more, unless you can bring proof. :p

There’s some interesting data in a 1999 paper from the BMJ about open review that compares authors’ and editors’ opinions about reviews (Table 4 here: http://www.bmj.com/content/318/7175/23), and authors are consistently more negative about most aspects of the review than the editors. Moreover, this doesn’t break out the data by the editorial decision, so it’s possible that these differences are stronger for negative editorial decisions.

Both authors and journals know that rejection is part of the publication process. For a journal, informing authors of a rejection falls under the professional sphere. But for an author who has invested time and effort first in research and then in writing a manuscript fit for journal submission, the decision of rejection is likely to evoke a more personal response. Authors face rejection several times, and submitting to a new journal means modifying the manuscript as per the new target journal’s guidelines. Thus, they find the journal publishing system hard to decipher and deal with. Journals could make the rejection easy to accept for authors by informing the authors politely of the decision while providing reasons that led to it.

“Does offering a consolation prize (“We’d be happy to consider your manuscript for publication in another [viz. lower-prestige] journal we publish”) help with rejection, or just rub salt into the wound?”

Speaking as an author, it all depends how the ‘consolation prize’ is offered. If it is a general open-ended offer, e.g. – “While we cannot offer publication at Cell/Nature/Science we’ll be glad to facilitate transfer of the manuscript for further consideration at another one of the journals of Cell Press/NPG/AAAS…”, thus leaving the specific choice of journal up to the author and implying that it might be suitable for another high prestige journal (albeit lower than the author’s first choice), that might help. If you recommend that the author submit to the lowest ranking option or megajournal that you publish, e.g. – “While we cannot offer publication in PLoS Biology, please consider publishing in PLoS ONE…”, you are telling the author that a work they thought one of their best efforts should go directly to the lowest prestige option you can offer, and that does not help, to put it mildly…

Rejections can be thoughtful and informative. They can also be mean and trite. If the editor is busy, it is awfully tempting to just shuffle along the referees’ comments without actually doing the editor’s job. That includes mediating the conversation between authors and reviewers, evaluating the manuscript and the reviews, AND commnicating to the authors why the decision was made. The latter can be difficult (yes I’ve done it for 10 years), but (a) you get quicker turn-around and (b) authors are more able to understand what went wrong. Never forget, however, that peer review is inherently a blunt instrument.

It makes me want to weep…

That’s what we heard from a peer reviewer in BMJ Open: our analysis made him cry, and now that’s part of the record 🙂

Peer reviewers are almost always anonymous, but editors seldom are. This can set up some curious dynamics in fields narrow enough that authors, reviewers, and editors know each other, and switch roles. When I experienced my first rejection from Journal A, my reaction was much the same as Phil Davis’s Cornell friend, just less restrained. However, I later had to admit that the editor’s rejection was based on valid criticisms, and after bolstering the data, re-working the analyses, and re-writing, it was accepted by Journal B a few years later, and my wrath at the injustice of it all waned. Ten years later our roles were reversed. Now serving as a subject matter editor at Journal C, I found a manuscript in my box from that same person who had been the editor at Journal A and who had rejected my treasured manuscript way back when. I must admit to a momentary visceral “what goes around, comes around” response from schoolyard days. Fortunately the reviews were favourable, and I ducked a potentially awkward situation. Still, it’s hard not to personalize and long remember rejection. Hopefully whatever the outcome reviewers and editors will strive to handle manuscripts in the same careful and respectful manner that they would like their own manuscripts to receive.