Read a recent update to this piece: PLOS ONE Output Drops Again In 2016.

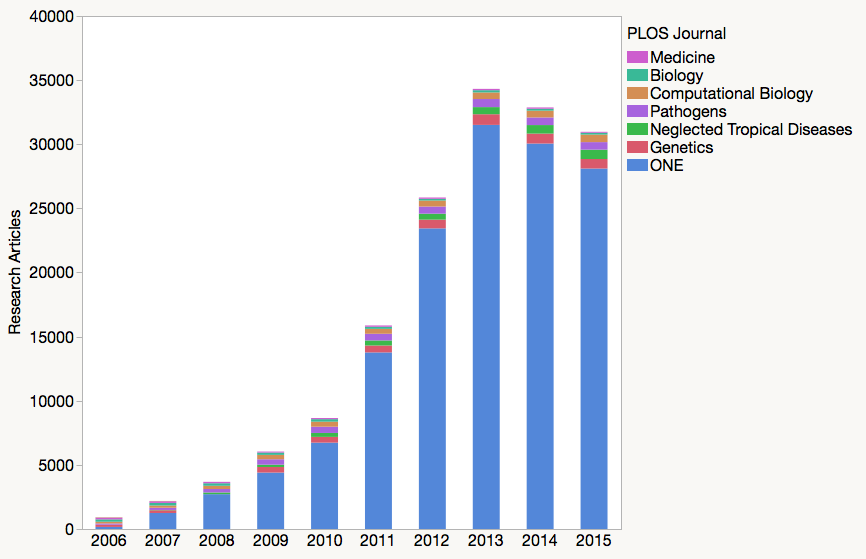

PLOS ONE’s 2015 Impact Factor is expected to rise, the result of its shrinking size. As reported earlier this year, the open access mega-journal has experienced two successive declines in article output, from a peak of 31,509 research papers in 2013 to 28,107 in 2015–a reduction of 3,402 papers or 11%.

Published each summer by Thomson Reuters, the Journal Citation Reports (JCR) includes various annual journal-level performance measures. The indicator most eagerly awaited is the Journal Impact Factor — a simple arithmetic average of the citation performance of a journal’s articles. Editors and publishers anxiously await this measure as it affects their relative ranking within their discipline. Authors, in turn, are heavily influenced by journal Impact Factors (often used to describe a journal’s prestige) as a guide for where to submit their manuscripts. While PLOS does not support the use of the Impact Factor, their authors seem just as interested in this metric as everyone else.

The Journal Impact Factor is constructed by summing all citations made to papers published in the previous two years and dividing by the number of papers published in those two years. There is a little more nuance to this approach, as the number of papers in the denominator is limited to research articles and reviews — what Thomson Reuters calls “citable items.” Whereas some journals publish many papers that are not considered citable (e.g. editorials, perspectives, commentary, letters, etc.), this is not the case for PLOS ONE. This will help simplify our example of how size affects Impact Factor calculations. In a future blog post, I will revisit and provide more detail on the classification and counting of citable items.

Last year, PLOS ONE received an Impact Factor of 3.234, which was the result of dividing 177,706 citations made in 2014 to 54,945 papers published in 2012 and 2013. We can further dissect the journal’s IF score into two separate parts, measuring independently how papers published in 2012 compare with papers published in 2013. For 2012 papers, there were 95,631 citations made to 23,447 papers for an effective Impact Factor of 4.079; for 2013, there were 82,075 citations made to 31,498 papers for an effective Impact Factor of 2.606. The reason why there is such a large performance difference between these two annual cohorts is that 2012 papers were measured in their third year of publication while 2013 papers were measured in their second.

The Impact Factor of a shrinking journal is therefore based upon the performances of more older papers, which tends to create an upward influence on its IF calculation. Conversely, a growing journal is evaluated on the performances of more younger papers, which tends to create a downward influence on its IF calculation.

What can we expect from PLOS ONE‘s next Impact Factor?

If we assume that PLOS ONE papers published in 2014 have a similar citation profile to papers evaluated last year, then we can expect its 2015 Impact Factor to rise marginally, from 3.234 to 3.360 or by about 4%. It is very difficult to get an actual performance reading, as the Web of Science (the index from which the JCR citation metrics are derived) limits citation reports to 10,000 records–just one-third of the papers published in PLOS ONE each year.

I should note that the above calculation ignores changes to the journal over the past year (data availability policy, publication fee increase, competition from other open access journals, platform upgrades and publication delays) that may change the kinds of papers submitted to PLOS ONE. Taken together, these changes may countervail the rise we expect from journal shrinkage.

Read a recent update to this piece: PLOS ONE Output Drops Again In 2016.

Discussion

11 Thoughts on "As PLOS ONE Shrinks, 2015 Impact Factor Expected to Rise"

Really? An entire post devoted to a trivial (and only predicted) increase in impact factor of a single journal? I thought we were all trying to stop obsessing about impact factors. And what is SK’s obsession with PLOS all about? (I also notice that nowhere in this post is there any criticism of the JIF either). Come on!

Hi Stuart,

First The Scholarly Kitchen has no obsession, no position, no agenda. This post is mine alone. I write about PLOS ONE frequently because it was a true innovation in science publishing. PLOS ONE has made a huge impact on other publishers and issues like its output and performance have an outsized effect on the journal market. Second, this isn’t an opinion piece. I try not to opine when I write, but base my arguments on data. Journal editorials and blogs are full of criticism and angry opposition to the JIF. If readers are upset that I’m not jumping on their bandwagon, they can simply go elsewhere.

Love or loathe the Impact Factor (and I’m not sure there are many who “love” it), it’s really valuable to understand how it works. If you want to criticize it, you need knowledge of it. If you’re running a journal, you need to deal with it in some way, so having a grasp on its nuances is useful. This post highlights something of which many may not be aware, similar to a series of posts we did a while back on Impact Factor Inflation:

http://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2008/05/07/impact-factor-inflation-what-causes-it/

and

http://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2010/07/12/impact-factor-inflation-when-an-increase-is-a-actually-a-decrease/

“I thought we were all trying to stop obsessing about impact factors.” Speak for yourself. Almost no one is trying to devalue JIF. And no one is obsessed with JIF. Obsession is a psychological disorder. The interest in JIF is as a proxy for one kind of merit. Only one kind, of course.

I can’t wait to see if you’re right, Phil. Your logic is solid, but the phenomenal growth of PLoS One created such unusual citation dynamics that predictions based on normal journal expansion were perilous.

I have to quibble on this point, though:

One the most common misunderstandings about JIF is that it is “a simple arithmetic average of the citation performance of a journal’s articles.” JIF is not an average, but a ratio: all citations that discernibly acknowledge the journal, divided by an estimation of size, based on the quantity of citable, or scholarly material.

Many critiques, and many over-interpretations of the metric (http://jcb.rupress.org/content/179/6/1091.full, http://www.ascb.org/dora/) spread outward from the difference between a true average and a ratio.

A true average could easily carry-along the article-level lineage, supporting full transparency, re-analysis, sub-analysis, and validation.

But that would be a metric other than JIF.

I agree with your point, Marie, and I attempted to provide additional detail after calling it “a simple arithmetic average.” Even Eugene Garfield conflates average article performance and ratio in his description of the Impact Factor (see: http://wokinfo.com/essays/impact-factor/)

The JCR provides quantitative tools for ranking, evaluating, categorizing, and comparing journals. The impact factor is one of these; it is a measure of the frequency with which the “average article” in a journal has been cited in a particular year or period. The annual JCR impact factor is a ratio between citations and recent citable items published.

I think Phil’s point about growing and shrinking journals “favoring” newer and older articles in their JIF calculation is a good one for those launching new journals to realize. New journals are by definition “growing”, and can be growing for the first several years of their IF calculation.

I’m actually predicting a large increase in PLOS One’s 2015 IF, but not because of the shrinking of output. First of all, your post cites the 2015 output as a reason for a rise in IF, but that content won’t be counted until the 2016 IF. But, by looking at 2013’s content and seeing how it performed in 2015, we can make comparisons with 2013’s content to how 2012’s content contributed to the 2014 IF.

2012 contribution to 2014 IF: 95,631 citations from 23,447 citable items, average of 4.079 cites per item

2013 estimated contribution to 2015 IF: 151,885 citations from 31,498 citable items, average of 4.822 cites per item. (I obtained this from Thomson by running lots, and lots of reports. Data saved, happy to share.)

So as you can see, article citations have increased by about 15%. The 2014 content would have to do quite poorly to bring down the IF from where it is now. So this should go up, regardless of the slowing of output.

Additionally, your statement of “If we assume that PLOS ONE papers published in 2014 have a similar citation profile to papers evaluated last year…” is a bit confusing. If we make this assumption, it would be impossible for the IF to go down.