Significant events have occurred in rapid succession in the last year signaling that preprints, the author’s original manuscript before submission to a journal, will play a much larger role in the landscape. Developments with DOIs, changes in funder expectations, and the launch of new services indicate that preprints will no longer be limited to the hard sciences and social sciences.

The success of arXiv was due in part to the fact that the high energy physics community had been sharing their preprints via email prior to the launch of the server which solved the problem of clogged mail boxes. Researchers value the ability to preview papers and receive feedback on their work prior to formal publication. Analyses have shown that a high percentage of articles in arXiv subsequently appear in the Web of Science, confirming their publication in a formal journal with an impact factor.

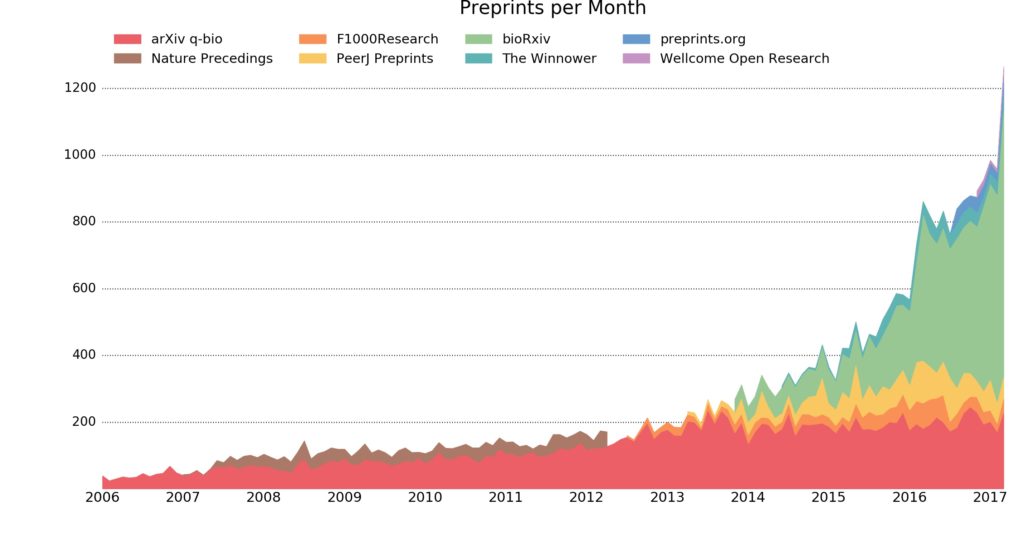

In contrast, other fields have lagged behind, specifically the life sciences and medicine which represent the largest area of the sciences. The chart below shows the growth of life science preprints per month from 2006-2017. Growth was sluggish until 2014 and grew as more options became available including bioRxiv, F1000 Research, PeerJ, The Winnower, and Preprints.org. In the last two years, the volume has tripled and much of the growth is attributable to bioRxiv. Wellcome Open Research is considered the newest addition and launched in November last year.

This chart was recently updated through March 2017 by Jordan Anaya using data from his search engine, PrePubMed. It appears on the ASAPbio site.

Preprint landscape

Beyond life sciences the level of activity indicates a recognition that preprints have value to their communities.

- The American Chemical Society (ACS) shared plans in August 2016 to collaborate with stakeholders in the global chemistry community to launch ChemRxiv. The goal is to advance the pace of scientific discovery and information dissemination. This will be a joint undertaking with Chemical Abstracts Service and is expected to have interoperability with various sources of chemistry related information.

- The Center for Open Science (COS) provides infrastructure branded as Open Science Framework (OSF). They have recently launched PsyArXiv, AgriXiv, SocArXiv and engrXiv.

- SciELO, the Scientific Electronic Library Online, is a decentralized platform that provides open access to more than 1200 journals from Latin America and Spain. They announced a preprint service that will be launched in 2018.

- The Social Science Research Network (SSRN ) provides a preprint service to individuals and university departments and has a core subject strength in economics and law. Established over 25 years ago, SSRN was acquired by Elsevier in 2016.

While all of this activity suggests that 2017 may be considered the ‘year of the preprint’, the success of these ventures will be determined over time.

Preprint servers put authors in control of when their research is released

The time to publication can extend 1-2 years from when authors first submit to the most prestigious journals and then undergo a full peer review with multiple resubmissions. An article in Nature (February 2016) asks: “Does it take too long to publish research?” It describes lengthening review periods over the last decade despite shorter production cycles.

Preprints permit dissemination to occur quickly, while allowing peer review to take the time required for certification. With preprints the author has control over when the results become public for feedback from their community and when they can claim priority of discovery. Preprints may be sufficient for distribution of certain research results, such as null results. Paul Ginsparg, who founded arXiv, notes that Grigori Perelman’s proof of the Poincare conjecture, for which he was awarded the Field Medal in 2006, appeared only in arXiv.

Concerns have been raised that preprints will be detrimental to publishers. However, some preprint services are providing ways to facilitate the transfer of content to publishers. In January bioRxiv enabled authors to post their articles to the preprint server and have their files forwarded to a journal for submission at the same time. eLife enables authors submitting papers to have them sent to bioRxiv at the same time. Many journals allow preprint posting and in an interesting shift, PLoS Genetics has designated three “preprint editors” whose job is to invite submissions from authors with preprints posted.

David Crotty moderated an SSP webinar on the “Future of Preprints” in November 2016. The panel included representatives of bioRxiv, SSRN and ACS to explore the potential role of preprints in scholarly publishing. All three speakers envisioned the co-existence of preprints and peer reviewed articles. While responses varied, expectations for the landscape were consistent.

- Discovery relies on Google Scholar and DOI links. DOIs for each version are necessary for clarity in archiving.

- Funding sources (donors, partnerships, etc) should be able to underwrite the cost of a service that is free for authors.

- Preprints may be reviewed for plagiarism, metadata and to detect junk science.

DOIs and funder acceptance legitimize preprints

Crossref announced in November 2016 that it had developed the appropriate schema and linking relationships for preprints and was accepting them as a content type. This means that an author’s preliminary work will be fully citable as soon as it is available, and can then be linked to the final peer-reviewed version wherever it is published.

Crossref has a policy regarding obligations and limitations for members depositing preprints. There are multiple benefits of having a DOI for preprints including:

- Auto-update of ORCID records to ensure that preprint contributors get credit for their work

- Preprint and funder registration to automatically report research contributions based on funder and grant identification

- Discoverability as the metadata is made available for machine and human access across multiple interfaces.

Crossref has expectations regarding permanent availability of preprint content. ACS intends to use Portico for archiving, for example. An additional concern to be addressed involves registration of revised versions. A surprising percent of submissions are revisions: SSRN indicates 40% and bioRxiv indicates 30%. Clearly identifying and preserving all versions may be an evolving topic for preprint repositories.

A major event occurred in January 2017 when Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI), Wellcome Trust and the Medical Research Council (UK) announced policies allowing researchers to cite their own preprints in grant applications and reports. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) followed suit in March. Twitter lit up with younger researchers reacting positively to the NIH announcement.

Proliferation of preprint services has attracted funder attention

ASAPbio is a scientist-driven initiative to promote the use of preprints in the life sciences. An initial meeting was held at HHMI early in 2016 to discuss the future of preprints. A good summary of the stakeholders’ views appears in Science (May 2016). Meetings with funders, technical experts and scientific societies were held to identify barriers to adoption. A progress report by Jessica Polka, Director of ASAPbio, appears in CSE Science Editor (February 2017) and identifies key factors that will affect preprint growth. These include:

- Cultural change

- Preprint policies at universities

- Preprints and scholarly journals

- New players and infrastructure

The proliferation of preprint servers apparent in this post has come to the attention of funders. Concerns have been raised regarding issues related to discoverability, permanence, and consistency across these services. In February 2017, ASAPbio received a $1 million grant from the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust to develop a new service to aggregate life sciences preprints and promote their visibility and innovative reuse.

Looking Ahead

These developments raise a number of questions:

- What is necessary in each discipline for preprints to take their place as part of the scholarly publishing life cycle?

- What does widespread adoption of preprints mean for the version of record?

- What implications does this trend have for libraries and institutional repositories?

- Will many publishers use preprints to identify and recruit potential submissions?

- Do preprints offer a solution for the publication of negative results?

- How long will it take to reach a tipping point where the majority of academic review and hiring committees recognize preprints as part of their body of work?

The role of preprints is clearly evolving in a way that will affect all stakeholders. The stars are aligning. Be sure to have your telescope handy.

Discussion

34 Thoughts on "The Stars Are Aligning for Preprints"

Judy, thanks for this overview. As the co-founder of bioRxiv, I have a starry-eyed view of the value of preprints in scholarly communication. May I clarify the statement about manuscript transfers into and out of bioRxiv? A manuscript posted on bioRxiv can be submitted directly to a journal at any time – for example, after rounds of comment and revision. This opportunity has been available for over a year owing to partnerships with Editorial Manager, Electronic Journal Press, and Bench>Press, and transfers into ScholarOne systems are coming soon. 100 journals are integrated with bioRxiv in this way and more are on the way. Since January of this year, bioRxiv’s Bench>Press submission system has enabled any journal to offer authors an additional service: transfer of a manuscript to bioRxiv immediately after the manuscript was submitted to the journal. eLife was indeed an early adopter of this service and others are in line. Authors are enthusiastic about both forms of manuscript transfer and the take-up rate of both is increasing.

Thanks for expanding on the development of interoperable workflows with journals. To the extent that preprint servers are networked within the existing environment, that will accelerate adoption.

To illustrate manuscript submission from preprint servers, a video: Transferring Manuscripts from Preprint Servers

Disclosure: I am in marketing at Aries.

SCOOPING PROTECTION Yes, preprints are here to stay, but despite improvements in alerting systems, there are limits to the extent we mere mortals can scan our areas of interest. For narrow specialists this may not be a problem, but cross-disciplinary readers are increasingly swamped. Abstracts of conference proceedings have long satisfied those who feel they need to claim priority and it was sad to see an EMBO Journal editor recently lauding the advantages of preprint submission as “scooping protection.” Authors and publishers alike should note that every item appearing to the world’s literature makes it marginally more difficult to savour that literature.

To the extent that the material is accessible on the Internet, it can be and is currently being searched by intelligent engines which are customizable to filter for particular needs. This includes images as well as full text. A number of these engines are free and customizable, others are managed by service providers. These are not limited to Watson and children.

As the original contribution mentioned, there is increasing inter operability to move documents across platforms and increasing standardization for identifying contributions. The “future” will track what is happening within the research community of increasing interdisciplinary work making such search technologies more important.

Many years ago, there was a proliferation of “Letters”, e.g. Phys Rev Let, which were quick, short pieces to get significant ideas out. Rapidly, these “letters” became the equivalent of journals, as the article here has noted with the publishing of the proof of Poincare’s conjecture.

As we have seen, over time, knowledge was transmitted via the written word with limited circulation, that was accelerated when we had print, including journals, and then e-mails. The movement of knowledge thru the social learning cycle suggests that the “rent seeking” nature” of traditional peer review journals may have “interesting times” ahead.

Are we at a point yet where we have data on the % of preprints that make it into print?

I can answer for Preprints.org: out of 1417 preprints online, we have found published versions of 526. That doesn’t take into account recent submissions that are still under review, of course.

Much appreciation to all who provided info on the preprint into publication rates. A great deal to think about what happens with those preprints that don’t make it into print. And, how to decrease the burden on readers of having to manually track down whether something was eventually deemed quality enough to print.

Hi Lisa,

Some longer term data on arxiv can be found here:

https://arxiv.org/abs/1306.3261

Worth noting is that publication behavior varies a lot depending on field. So one of the fields where one sees lowest formal journal publication of former preprints is computer science, but that’s because much of what is considered “publication” for that field happens through meeting proceedings, rather than journal articles.

Thanks. Ultimately, the actual % matters less than the reality that it isn’t 100%. So, regardless of whether a particular something ends up published, there is the load on the reader to find out that yes it was/no it wasn’t. Would be nice if the systems could make that less taxing regardless of the % that eventually achieve an additional status in the field.

Two years after posting, 60% of manuscripts on bioRxiv have been published in a journal. We use an automated process to find the published versions which may fail if the preprint and published paper have significantly different titles or authorship, so 60% may be an underestimate.

For arXiv, I’ve seen research that varies from the high 60s to 80% depending on the years and tools that were used.

I would like to add that even authorship platforms, like Authorea, are moving into the preprint space. Recently, we introduced the ability for authors writing on Authorea to issue a DOI to their content. By doing this we became the first and only preprint repo to allow researchers to post their preprints in full HTML5. We’re working directly with a growing list of publishers too for direct submissions.

The following links explain more.

Preprinting at Authorea

https://www.authorea.com/users/8850/articles/155312-introducing-the-21st-century-preprint-html-versioned-citable-data-rich

Direct Submissions to eLife

https://www.authorea.com/users/8850/articles/149449-elife-and-authorea-partner-to-simplify-submission-for-authors

Direct Submissions to AGU

https://www.authorea.com/users/8850/articles/158670-american-geophysical-union-and-authorea-partner-to-offer-one-click-submission-of-manuscripts

Direct Submissions to Rockefeller University Press

https://www.authorea.com/users/8850/articles/160096-rockefeller-university-press-authorea-make-collaboration-and-submission-easier-for-authors-through-partnership

Josh (founder of The Winnower & chief research officer at Authorea)

Thanks for this post, Judy. I think that preprints in the life sciences are going to be doing well because they address several author pain points, rather than just one.

I wanted to comment on the inclusion of Wellcome Open Research in a list of preprint servers. I recall that Wellcome took some pains when they first announced WOR to be clear that it was NOT a preprint server/service at least in any traditional sense: once a paper had been submitted to WOR, it could not be legitimately submitted elsewhere. I think that’s a pretty important part of the definition of “preprint server” that the community understands. Of course, if the definition is “not peer reviewed materials that are posted and then undergo review in place”, there is a larger scope including WOR and others shown in the graphic.

I think authors will want to be clear on this point of whether papers once posted can go on to a journal of the author’s’ choice. I think this is one of the advantages of preprint servers: they separate posting from publication choices and (as you said) keep the choices up to the authors.

I agree that F1000Research and Wellcome Open Research are not preprint servers in the sense of bioRxiv, PeerJ Preprints, and preprints.org, however if you submit a manuscript to F1000Research/Wellcome there is no reason to post it on a preprint server since they are already publicly available with a DOI, commenting, metrics, etc. For that reason I decided to index them in PrePubMed.

Given the pervasiveness of the graph above (popularised by ASAPbio), I think it would be interesting and important to put this in context of the total submissions to arXiv. The graph here specifies that by arXiv it means q-bio only, but I have seen versions of this already that don’t make that distinction.

I suspect we will only be able to truly predict how important preprints are becoming if we can place this recent growth in preprint submissions (in particular to biorXiv) in the context of the total preprint universe.

Disclosure: I work at Springer Nature. Opinions are my own.

Yes, unfortunately Nature News adopted a version of the graph made by Jessica Polka and mistakenly labeled arXiv q-bio as arXiv:

http://www.nature.com/news/2016-in-news-the-science-events-that-shaped-the-year-1.21159

In a subsequent post they did correctly label arXiv q-bio and compared the preprints to total arXiv submissions:

http://www.nature.com/news/heavyweight-funders-back-central-site-for-life-sciences-preprints-1.21466

This still isn’t the total preprint universe though, for example there are social science preprints etc.

Acknowledging that there are differences in the size of disciplines and that none of these are comprehensive – monthly growth rates appear to be:

arXiv ~9,000 after 25 years with Physics, Math, Computer Science

SSRN ~5800 after 23 years mostly social sciences

Life sciences ~1200 for 6 different servers; was hovering ~200 until 3 years ago

How is the general reader going to distinguish articles in preprint services from peer reviewed articles? Growth of these services along with the recognition from funders and others seems to belittle peer review, contrary to surveys of researchers that indicate peer review is stilled valued.

This is how the preprint status of a manuscript is called out on bioRxiv, with a link to text on the site that explains in detail what an unrefereed preprint is. Most preprint services have some variation of this

doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/127993

This article is a preprint and has not been peer-reviewed [what does this mean?].

For Preprints.org, we put a very visible banner on the article page and in the article PDF with a link to the peer reviewed version if it’s available. Crossref and dois make this relatively straightforward to do.

bioRxiv and Preprints.org do, indeed, have very useful flags to users about the lack of peer review, as well as useful prominent links to the published version (bioRxiv’s in red and Preprints’s in green). But several newly established preprint servers lack these useful functions, and this lack is really a disservice to researchers. Some of the recent launches also seem to allow posting of the peer-reviewed manuscript and/or the published article, which further confuses preprints with peer reviewed publications.

I am particularly interested in the “Preprints may be sufficient for distribution of certain research results, such as null results.” statement. I think that’s accurate, but I’m curious if anyone knows of any data showing that researchers are actually using pre-prints in this way. Same for replications, actually.

Are you defining ‘null results’ as evidence that doesn’t support a scientific hypothesis (sometimes also called ‘negative results’)? bioRxiv asks authors to describe their results as ‘new’, ‘confirmatory’, or ‘contradictory’. ‘Contradictory’ isn’t always the same thing as ‘null’ perhaps but for what it’s worth, contradictory results account for 1% of the manuscripts posted to bioRxiv.

Thanks for your response, I was mostly thinking about null results in terms of addressing the file-drawer problem. Meaning, results that showed the experiment didn’t work out in some way. Stuff that, barring pre-registration, probably wouldn’t be published.

I guess it is also not the same thing, but would it be reasonable to assume that replications on bioRxiv are folded into the “confirmatory” category?

Yes, that’s a reasonable assumption. 2% of bioRxiv manuscripts are described (by their authors) as ‘confirmatory’.

Just out from the Center for Open Science. Public Goods Infrastructure for Preprints and Innovation in Scholarly Communication https://cos.io/blog/public-goods-infrastructure-preprints-and-innovation-scholarly-communication/