Technology has had a significant, rapid and often random impact on a variety of industries. Scholarly publishing is not exempt from this. Depending on your perspective, it might feel like you or your business is being bounced around at random. But from a different perspective, that the same experience could be entertaining, even exhilarating. Often it is confusing knowing whether the ball being bounced about is you personally, your company, or your organization’s products or services. Are you driving the game, or are you simply at the control of the various factors that influence your environment? This feeling could apply if you are an executive at a publishing house, a librarian in an institution, or a developer at a technology provider serving our community.

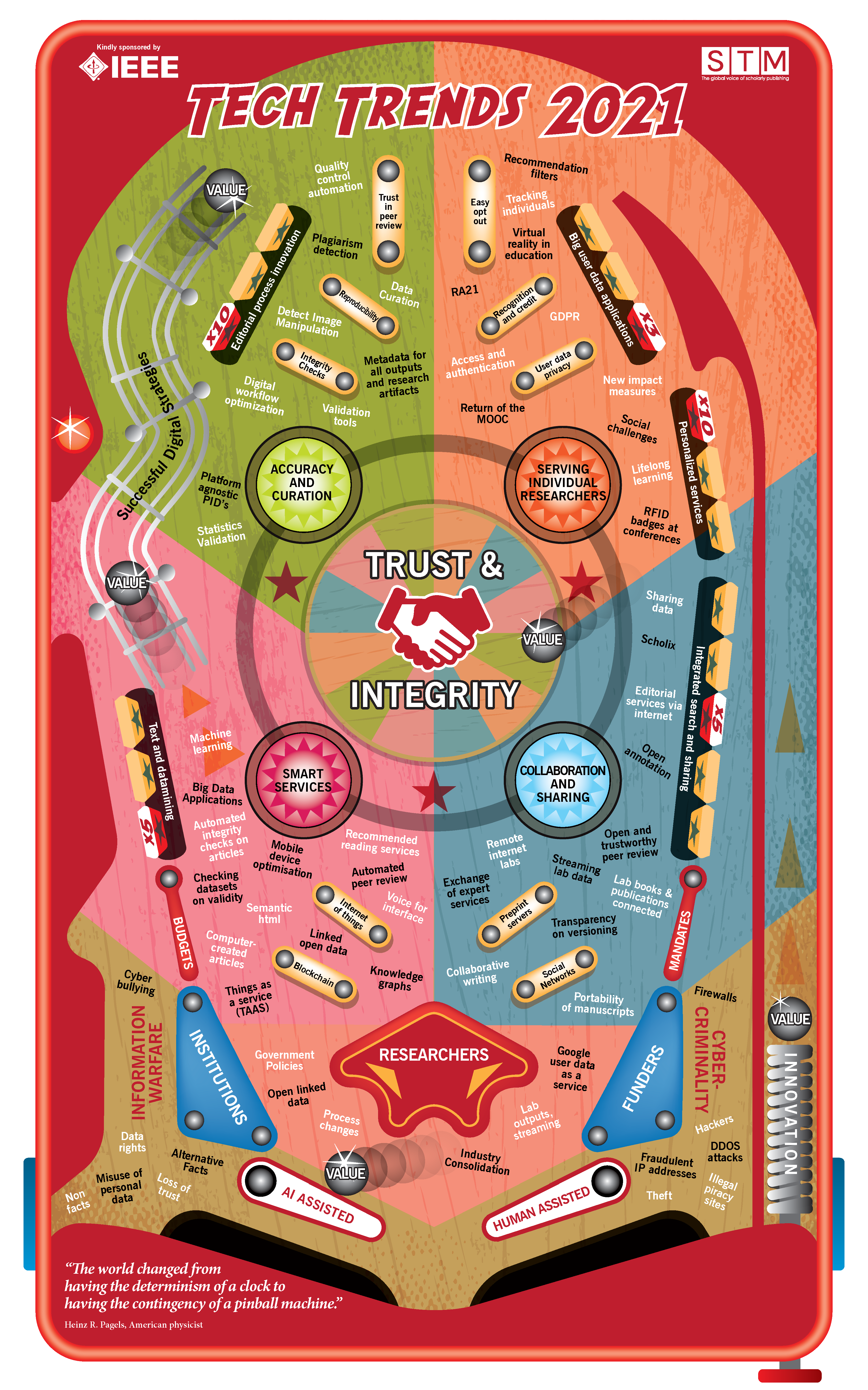

This is the landscape as it was envisioned by the members of the STM Association Future Lab Committee as it considered the complex technology landscape we find ourselves in at the moment. This environment harkens back to a quote from Heinz Pagels, from his 1982 book The Cosmic Code: Quantum Physics as the Language of Nature, “The world changed from having the determinism of a clock to having the contingency of a pinball machine.” Although Pagels was focused on the fading principle of determinism in physics, with the development of quantum physics, the subsequent impact of this changed perception of reality has had far reaching implications. Building on Pagel’s quote, the Future Lab group envisioned the new environment of our community as a giant pinball machine, with different components ricocheting the “ball” of value around the field of play, buffeted by bumpers, and potentially high-scoring opportunities in service of various areas. Just like a true pinball machine, there are risks and gutters where one’s ball can be lost.

The Future Lab has been looking at technology trends impacting the scholarly communications world for several years now. Last year, the group extended its timeline to focus on trends that would be significantly impacting our community four to five years from now. This year’s STM Top Tech Trends scan covers the period through 2021. The group met to brainstorm in London last December and worked through the winter to hone its ideas. The final version of the visualization was released late last month during the STM Association spring meeting in Washington.

The vision of the landscape as a pinball machine continues the theme of imaginative graphics to depict a complex landscape. Last year’s work was captured as a treacherous sea with various waves buffeting the small boat of scholarly publishing, which was described in another post last year. This year, the roiling ocean is replaced with the field where the value of serving the customer is bounced among various bumpers and targets where points can be scored and value added, but risks remain; where value can be lost and one can end up losing the game. Sam Bruinsma, Senior Vice President Business Development at Brill and Chair of the STM Future Lab Committee, commented that he was pleased to see publishers being more proactive players in this year’s visualization than being a poor ship tossed by a potentially perilous waves and currents.

“The world changed from having the determinism of a clock to having the contingency of a pinball machine.”

The ball in this visual metaphor is launched through innovation onto the playing board, with the ball representing value for all of scholarly communications, including researchers, libraries, and publishers. The flippers that keep the ball in play are Human and AI assisted technologies that support the value chain process. Additional support propelling the ball is provided by institutions, both libraries and other institutional support infrastructures, as well as funding organizations.

The overall board is divided into several sections around the key themes of integrity and trust. These core values are critical elements of what it means to provide scholarly information, that is vetted, reviewed and that people can rely on. This can be delivered through a focus on the four core elements, which extend outward from the center of the playing field, which are foundational elements of the value creation at the center of the experience. These components are Accuracy and Curation, Serving Individual Scientists, Sharing and Collaboration, and Smart Services. Around each of these sections are various elements or trends that are related to those elements.

The segment that deals with accuracy and curation includes the elements related to the editorial process. It is envisioned that there are significant bonus points to be earned through editorial process innovation. The value-ball can bounce between the elements on trust in peer review, reproducibility, or automated integrity checks. Other important elements in this segment are validation tools, plagiarism detection, image manipulation detection, statistical validation, quality control automation, digital workflow optimization, data curation, metadata creation for all outputs. There is also an opportunity here to “relaunch the ball” via implementing successful digital strategies.

A second segment highlights opportunities to build value with the potential for smart services. In this part of the playing field, the most obvious points to be gained are the provisioning of text and data mining services. In this area, potential developments related to the Internet of Things, and Block Chain, as well as machine learning, and other big data applications. Here too automated integrity checks, computer assisted recommended reading lists, knowledge graphs, and linked open data are all potential services publishers could build value upon. Mobile device optimization and the voice as a machine integration service as also important features. Further developments are also possible with automation of peer review, or the provision of things as services could also impact our experience in the years to come.

The third component of this landscape is focused on the potential to serve individual researchers, not simply serving large communities of users. Here, it was envisioned that the most bonus points resided in the application of large-scale user data to personalize services. Of course, balancing this are concerns about user data privacy, the new General Data Protection Guidelines in the EU, the ability of users to opt out, and how individual user behavior can be tracked. Other elements of this have to do with access and authentication, and recommendation services. This also fits into the broader issues around, the social challenges of all this change, the recognition and credit elements, as well as how new impact measures are being formulated. These elements touch on the lifelong learning trends, as well as the continued developments related to MOOCs.

The final board segment includes the increasing amount of collaboration and sharing taking place. How well search and sharing is integrated with other services is seen as the biggest opportunity for added value. Within this space, the expansion of preprint servers, and social sharing networks are dominant feature. Other elements of these sharing networks include the sharing of data, streaming lab data, remote lab environments. Collaboration incudes a variety of other elements as well, including the portability and sharing of manuscripts, open annotation, collaborative expert services, and editorial services, even collaborative writing.

Not all of the opportunities on the field of play are opportunities for success. One can lose value as well by falling into the “gutter”, so to speak, on the pinball field. These areas are labeled as information warfare and cyber criminality. On the side of information warfare are things like alternative facts, the misuse of personal information, and cyber bullying. On the criminality side, there are pirate sites distributing content, hackers, distributed denial of service attacks, and outright theft. If one does not play well, or even if one is just hit with bad luck, the consequences of these negative trends could be dire.

One might notice several components in our community are not included in this landscape, notably publishers or libraries. They are envisioned as playing the game, trying to track up points by serving the researcher community. Of course, just like a pinball machine there are potential ways that these or other players could “tilt” the game through external disruptions, of which one could consider many, such as disruptive technologies or services, political or economic changes, or even social changes that could develop over the next five years. Because this group is focused on technological changes impacting our community, the visualization doesn’t capture those external impacts, such as changes to peer review, developments in open access, funding or political changes that may take place are not captured, nor are components of the group’s remit.

We can now see that these new technologies are either now beginning to, or soon will begin to impact scholarly communications. Realistically, executives need to be thinking about these technologies and considering what will be the impact on our community, and their own organizations

Who is to say which of these technologies is appropriately “scored” in this pinball metaphor. There is no way to know whether bumping up against the “internet of things” or “privacy of user data” will be more paramount five years from now. However, we can now see that these new technologies are either now beginning to, or soon will begin to impact scholarly communications. Realistically, executives need to be thinking about these technologies and considering what will be the impact on our community, and their own organizations, if these technologies really begin to take off. They also need to start thinking how they wish to interact with these new opportunities: if the ball interacts in the right way, you add value and can even relaunch your game in terms of ‘successful digital strategies’, as in the rail on the upper left. Might block chain be used for circulation management, or protection of user privacy in the secure sharing of research data sets and therefore need to be something that publishers adopt or become fluent in its application? Is it possible that authors and editors will expect that the majority of publishers have tools in place for automatic plagiarism detection or the ability to detect image or data manipulation to prevent fraud? How will authentication change and how will user activity be supported and tracked base on that new system, particularly in light of new privacy legislation, such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GPDR) in the EU?

The challenge with any technology forecasting is that the pace of innovation is so rapid and can take many rapid turns. Five years ago, in the New York Times, there was an article predicting the 32 innovations that will change our future. A few of the items, like better oxygen levels on some air planes, are possible now (and the Dreamliners are lovely experiences, if you have the opportunity). Things like the forthcoming bandwidth crunch, are conceivable depending on where you are and the market you are in. I’m still looking forward to the world without hangovers. And despite the improvements because of apps like Waze, a world without congestion still seems a long way off. Realistically, I think the Future Labs group has done at least as good a job as the NY Times team did five years ago. We may just have to wait to 2021 to know for sure.

Discussion

5 Thoughts on "‘The Contingency of a Pinball Machine” – The STM Future Lab Looks Forward to Technology Trends in 2021"

The infographic looks snazzy no doubt, but if you need a whole companion text to explain what it represents then it’s just a bad visual metaphor that fails to communicate what it’s meant to convey.

This is a great image! As a consultant, I’d love to hang a copy of it over my desk as an ongoing resource. (At least until it’s out of date — maybe next month?)

My career in publishing, reaching fifty years in 2017, has been vastly affected by technology. When I started, there were no photocopy machines, and secretaries (yes, that was what they were called then) were skilled in shorthand so as to be able to take dictated letters. Our printing plant at Princeton University Press was still using hot-metal typesetting and flatbed presses for printing. Designers had to laboriously do mockups of jacket designs’ copyeditors still used blue pencils on paper texts. In retrospect, that era feels like the publishing Dark Ages, yet we were still able to publish books of fine quality, using acid-free paper, sewn bindings, and durable materials. In some respects the quality was higher in those days than it is now. Indeed, going even further back, I own an incunabulum from 1483 that is bound in vellum and printed on paper that makes it look as fresh today as it did almost 500 years ago! So, not all technological progress is really progress.

I would argue the things that publishers were chasing in 1483 are still priorities for publishing, but the digital revolution has changed the worth people see in these physical objects. Books were originally created in the first place to serve something intangible (the communication of ideas and knowledge), and technology has given us much better ways of doing this. For things where people really want high-quality, long-lasting physical products for their aesthetic and emotional value, they are still out there – for example the Folio Society’s offerings of classic books. But the original purposes of producing high-quality physical texts are now served in far more radical and effective ways. Distribution and accessibility, it goes without saying, has been made far simpler with technology. The longevity of the content is now more assured than ever – it can be distributed in a millions digital copies with virtually no effort, and there will usually be master versions in the cloud and various digital archives. And then, if you want something that is both informative and beautiful, I would suggest that interactive online data visualizations are frankly awe-inspiring examples of how technology can achieve this. If we think of these digital productions as commonplace and of older physical texts as somehow more worthy, this might be our mistake, not the mistake of technological progress!

Ah, but can technology really ensure longevity? NASA notriously ran into problems in accessing older data and records when technology changed. There are businesses that keep older machines just so that old floppy disks, e.g., can be read. It may still be true today that a book from 1483 will outlast media that use technology today that will be superseded tomorrow.