Each spring during its annual US meeting, the International Association of STM Publishers (STM) releases a view of the top tech trends impacting scholarly publishing. That STM Future Trends for 2020 was released last Thursday. For the past two months, the document had been circulated among STM members internally. It’s now available for the community to engage with and discuss.

Each spring during its annual US meeting, the International Association of STM Publishers (STM) releases a view of the top tech trends impacting scholarly publishing. That STM Future Trends for 2020 was released last Thursday. For the past two months, the document had been circulated among STM members internally. It’s now available for the community to engage with and discuss.

During the Annual US meeting of STM last week, I sat down with Eefke Smit, the Director of Standards and Technology at STM, and Sam Bruinsma, Senior Vice President Business Development at Brill and chair of the STM Future Lab Committee to discuss the team’s output. STM has been organizing this Future Labs effort annually for more than 5 years. The forum is comprised of around 30 members from a wide range of publishing organizations, both commercial and non-profit, and both small and large.

For those not familiar with the process, the group meets in London in December to brainstorm ideas for half a day. They then coalesce the brainstorming output into broad themes to cover those issues, using Delphi technique to forecast technology trends through a panel of experts. Following the brainstorming, the group then comes to consensus about the key technology factors impacting the publishing community. Previous output from the group is available for 2015, 2014 and 2013. Compared with other community technology trends efforts, what separates the STM Future Labs is the fact it is a collaborative team effort among publishing organizations. This year the group took a longer-term view of technology impacts on the STM publishing community, extending out five years rather than simply looking to the next year as in previous iterations. The group also focused on somewhat different dimensions that are impacting the publishing industry, such as security, policy, research practice, and end-user interactions, as well as how those trends are interacting and impacting each other.

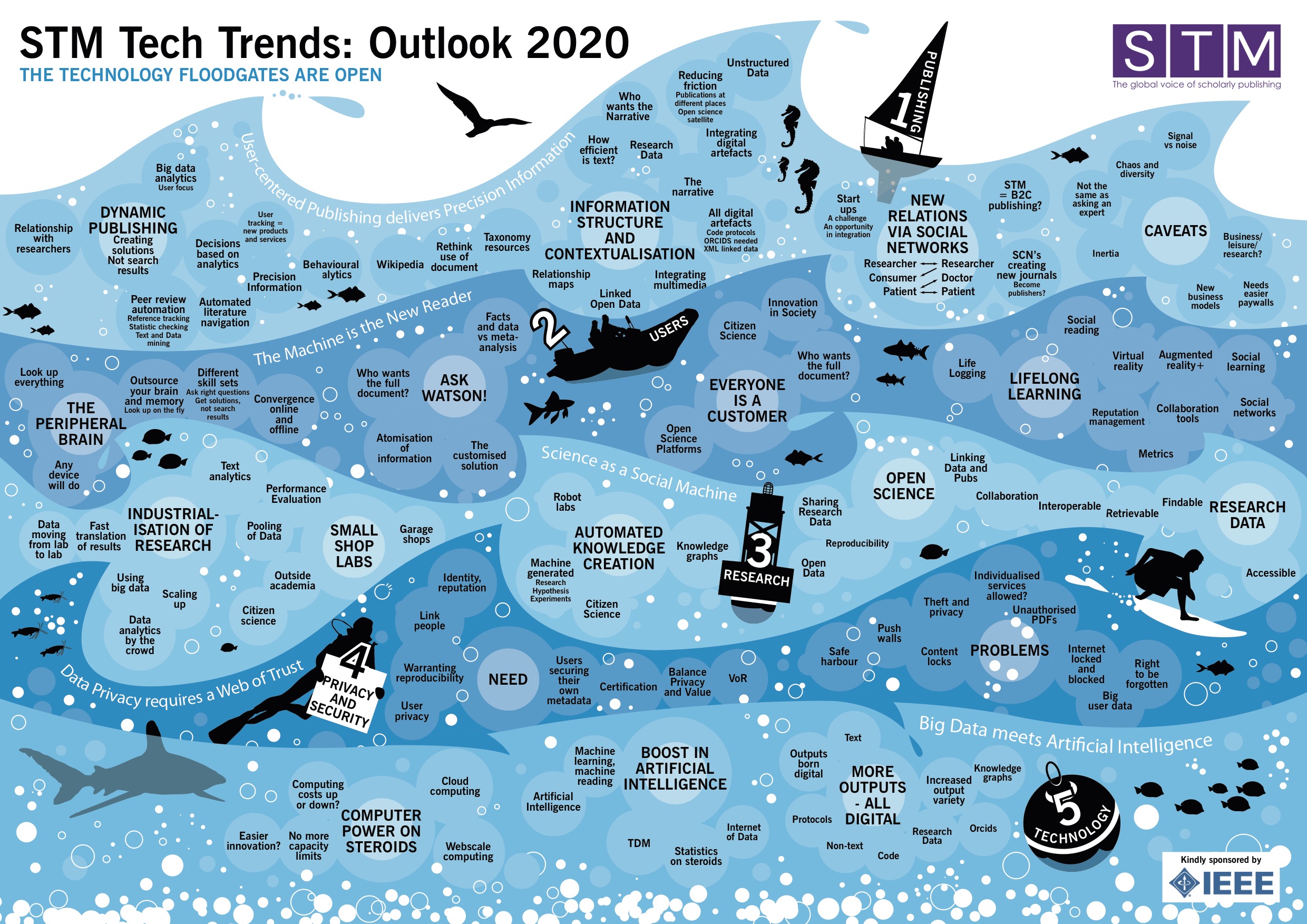

The primary output of the group is a visualization of issues in the landscape. That image is best understood from bottom up and left to right, despite the numbering. The technology layer is at the base of the visualization. Technology underlies much of the modern scholarly communications system and is in a constant state of flux. Driven by rapid increases in power, availability, and the reductions in cost, technology is empowering researchers and users, while also increasing their expectations. In addition, technology is expanding the range of publication outputs publishers must interact with. Moving up the image, the privacy and security layer, is where the technology and policy begin to intermix. Security is both a technological issue, but one that is driven by demands and needs for trust, conformance, and certification. There are also a variety of challenges facing publishers that is driving a focus on this space, such as piracy and rapidly changing legal frameworks.

In the next layer of this seascape is the evolution in research activity, such as the increased focus on research data as a first-class research output, the automation of knowledge creation through embedded sensors, knowledge graphs and the democratization of scholarship. User-related issues comprise the next layer. The surprising thing about this layer is its focus as much on machines as people. In the digital world scholarly publishing inhabits, the machine as a reader of content is nearly as important as the human reading the content and the group saw this as a trend that will only increase in the future. Finally, the publishing community sits atop these churning currents. What is described as dynamic publishing, which is focused on a variety of interoperable content forms driven as much by user behavior and analytics as it is by content and pre-production. Delivering information will include much more than the provision of a full-text PDF. It will include extraction and combination of content to provide meaningful answers to questions posed by researchers.

One example of this would be how a user gets the dynamic solutions to their query and not a search result list. A research might have a question, say as a climatologist who is researching a specific question on temperature fluctuations throughout the 20th century. Today, a search on this topic might provide the researcher with long hit list of potential articles or possibly resources that might contain that data. In the future, the group expected that a dynamic publishing environment would provide the user with the answer to their question, rather than potential sources. To provide this experience, publishers would combine the digital technology stack, access to open content, research data, and the advanced computational resources to provide real-time analytics to synthesize an answer to questions. The systems will be ‘intelligent’ enough to provide the aggregated knowledge from those relevant resources.

Sam Bruinsma described it this way: “The smart article is the one that finds the user, not the one that the researcher has to find. We are finally beginning to understand what that environment will look like and what are the critical elements to bring that to fruition.” We can start to see glimmers of this future with tools like Wolfram Alpha, Apple’s Siri, and IBM’s Watson. “The jewel for publishers and users will be in precision information,” commented Eefke Smit.

This layering is obviously publisher-centric and others might view this as myopic, but it’s important to understand the perspective and goals of this project. While there are other larger trends, other communities that are affecting scholarly publishing, this model is mainly focused on the STM publishing world. This a strategic vision for trends impacting publishers, not libraries, scholars or the academy writ large, although there are certainly interactions and overlaps. A similar effort by the library community might likely yield different priorities.

There are a range of opportunities and potential challenges for publishers encompassed in this effort. Sam Bruinsma said, “Many of these things are not realities that publishers must ‘do something about’ but rather are things they need to be aware of may need to react to.” The challenges are exemplified by the shark in the bottom left and there were many jokes about what the shark represented.

This isn’t a vision of what STM publishing will facilitate tomorrow, or even next year. By taking a longer view, the group was able to extend its vision of an ecosystem within which STM publishers will have to function. The visualization provides publishing leaders with a description of some of the infrastructure elements that need to be developed, the tools and user expectations, as well as the external currents that are exerting influence on scholarly publishers.

Hanging out in the top right — in a fashion the opposite of a footnote — are a set of caveats to the entire model of the future. These caveats will need to be addressed. Subsequently, policies will need to be worked through, and once developed will need to be adopted. For example, NISO’s work on patron privacy principles is still in its earliest stage of deployment. A set of principles have been developed and are being circulated, but what implementation of those principles will look like continues to develop. It will take some time to generate the infrastructure to support some of those principles. Just as it will take years for the culture around the sharing, use, citation, and assessment of research data sets in the traditional publication process to evolve. Another major factor influencing the movement toward these solutions is the simple fact of inertia. The academy, and therefore scholarly communications, are notoriously slow to change or adapt. Many ideas and approaches to improving scholarly communications have been proffered over the years, yet many have languished. Another key element of this, of course, are the business models that will support this infrastructure and exchange of ideas.

Many topics from previous years have been sidelined in this version of the STM tech trends. The scholarly article used to be squarely in the center of publishing worldview and its vision of the future. For example, reflect on the “article of the future” effort a few years ago, which included many of the elements of this revised vision but it was packaged in the context of the traditional article. Other research objects have been incorporated as stand-alone objects into this new vision. Also, the atomization of content is drawn out, so content within the article that can be extracted rather than the package (of the article, the book or the journal), which is another trend that has been identified. Content is no longer viewed as being contained in a single form, but it is being imagined within a graph of scholarly outputs (described best by OAI-ORE). Open science, while present, isn’t the contentious or challenging item for STM publishers it had been in previous year.

The visualization captures a lot, but it is also a bit overwhelming. But this is a result of the environment, not of a lack of focus. The scholarly communications landscape, the technological infrastructure, as well as the social and policy frameworks in which STM publishers operate are rapidly shifting. The consolidation into even five dimensions, with three to five component elements is a feat of consolidation. This is all “rolling the boat of publishing floating atop these trends” as Eefke described the boat labeled Publishing at the top of the image.

Before beginning a panel conversation on future technology trends that followed Eefke Smit’s presentation of the Future Trends, Chris Kenneally, Director of Business Development, Copyright Clearance Center quoted from Shakespeare about the visualization and our environment:

“There is a tide in the affairs of men.

Which, taken at the flood, leads on to fortune;

Omitted, all the voyage of their life

Is bound in shallows and in miseries.”

– Brutus in Julius Caesar Act 4, scene 3, 218–224

This complexity also provides a great deal of opportunity upon which publishers could seize new opportunities and “lead on to fortune”. The 5-year window of this project makes more sense in the context of product development. If a publisher wants to have a product as described in this model, in reality, the work to put those systems in place by 2020, publishers need to start working on them now. Time flies and 2020 isn’t nearly as far away as we might like to think.

Discussion

8 Thoughts on "STM Future Trends 2020 provides publishers insights on the currents affecting them"

Question answering technology is coming along but it is not clear what role publishers have to play, other than making their journals part of the global knowledge base for the answer engines, plus maybe making these engines accessible from the journal websites. A good answering system will be mining all the journals related to the question, not just those from a single publisher.

These two statements seem like something of a contradiction:

1. “The academy, and therefore scholarly communications, are notoriously slow to change or adapt.” (Paragraph 10)

2. “The scholarly communications landscape, the technological infrastructure, as well as the social and policy frameworks in which STM publishers operate are rapidly shifting.”

(Paragraph 12)

If scholarly communications are slow to change how can the landscape be rapidly shifting? As a technology forecaster, I would think that this “notorious” inertia should be factored into the forecasts. Actually we are talking about millions of people and tens of thousands of organizations and journals. Five years may simply not be the right timeframe for major change. Not that nothing is happening, quite the contrary, but technology folks do tend to underestimate the required efforts.

David, The two statements are not contradictory and I’ll give you a few examples of what I mean:

Scholarly communications is slow to change in the sense that the reward strcutures around publication are presently journal focused (or monograph focused, depending on the domain). Other forms of scholarly output, such as data sets, software, non-traditional publishing, or other grey literature, generally won’t add to one’s P&T portfolio. Traditional recognition systems based on journal publishing, (impact factor scoring, etc) remain deeply entrenched in the academy. This form of social inertia is hindering the advancement of open access in some spaces, the increased sharing of research data, and the adoption of new forms of communication or sharing. Granted, these things are happening, but at a much slower pace in the academy than they are in other fields. Another example is that while many mandates for scholarly publishing via open access have been proffered, few have been tied to financial resources to support that OA publication.

On the side of the frameworks that support scholarly communication, some things are changing rapidly. Technologically, most of the changes are being driven from outside the scholarly communications space, such as the shift to mobile content delivery, engagement with resources at the space of need, natural language processing and machine learning. On the legal side, a great deal of the copyright, digital rights management, privacy and security frameworks are again primarily driven by other industries, but which the STM world must react to.

The landscape is shifting, driven not by the academy of publishers, but by outside forces. While those changes are underway in the broader communications landscape, the academy is slower to respond. Hopefully, that is more clear.

Thanks Todd. So from a technology assessment standpoint it sounds like there are several technologies with high potential impact but low probability, as far as widespread 2020 implementation goes, given the inertia of the system.

There also may be a touch of advocacy here. You speak of some of these changes as though they were needed or desirable, but as an industry analyst I do not make that judgement. My goal is to try to figure out what is likely to happen. Five years is an unlikely schedule for major changes in such a highly distributed social system.

I’m puzzled by not finding the term “open access”. Does the STM Assoc. think that by 2020 all scholarly publishing will be open access publishing and that everybody takes that for granted or -just the opposite- does STM Assoc. think open access can be neglected (despite i.e. http://www.oa2020.org ) and hence it’s not worth mentioning the term?

During my talk with Eefke and Sam, we did talk a bit about OA. The rationale for not including it was two fold. First, OA has already been generally accepted by most publishers, though in different forms and with different terms — I’m not going to get into the well-trodden discussion about what constitutes “open access”. Today, nearly every major publisher is providing an option for OA distribution. Again OA advocates might disagree with how open those publisher’s OA policies actually are, but the fact is that open access is already a significant model in scholarly publishing. In addition, the technological questions about OA are fairly straight forward. The main challenges for OA are related to business models, funding, sustainability, and policy (like mandates). While OA will certainly be a trend impacting STM publishing, I don’t see it being a technological trend. Easier access to content via OA might facilitate some of the computational trends discussed, but it is not necessary for those trends to be possible (easier, yes, with OA content but not impossible with subscription content). Finally, OA could be viewed in the context of “Open Science” in the Research current.

Actually, on the OA front the US Public Access program is leading to the development of some remarkable technologies. For example, CHORUS and Crossref are working to integrate publisher websites with the emerging federal Funding Agency repositories. Much of this technology has yet to be developed. What the final system will look like, or do, is far from clear.

In this context The Optical Society has developed an interesting artificial intelligence approach to help solve the vexing “funder identification problem.” See their recent paper at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK350153/

Then too, SHARE is doing some very promising software development for its emerging “research event notification” system.

All of this and more are on an exciting timeframe of around five years.