Editor’s Note: Over the past several years, some online commenters have uncovered examples of publishers failing to make freely available articles for which an article processing charge had been paid for that very purpose. After raising this issue recently in response to a Scholarly Kitchen posting, one of our regular commenters investigated the issue more closely. This is his report. Charles Oppenheim is a Visiting Professor at Robert Gordon University, Aberdeen, UK and at Cass Business School, London, UK, and is also an independent consultant on intellectual property rights and scholarly publications.

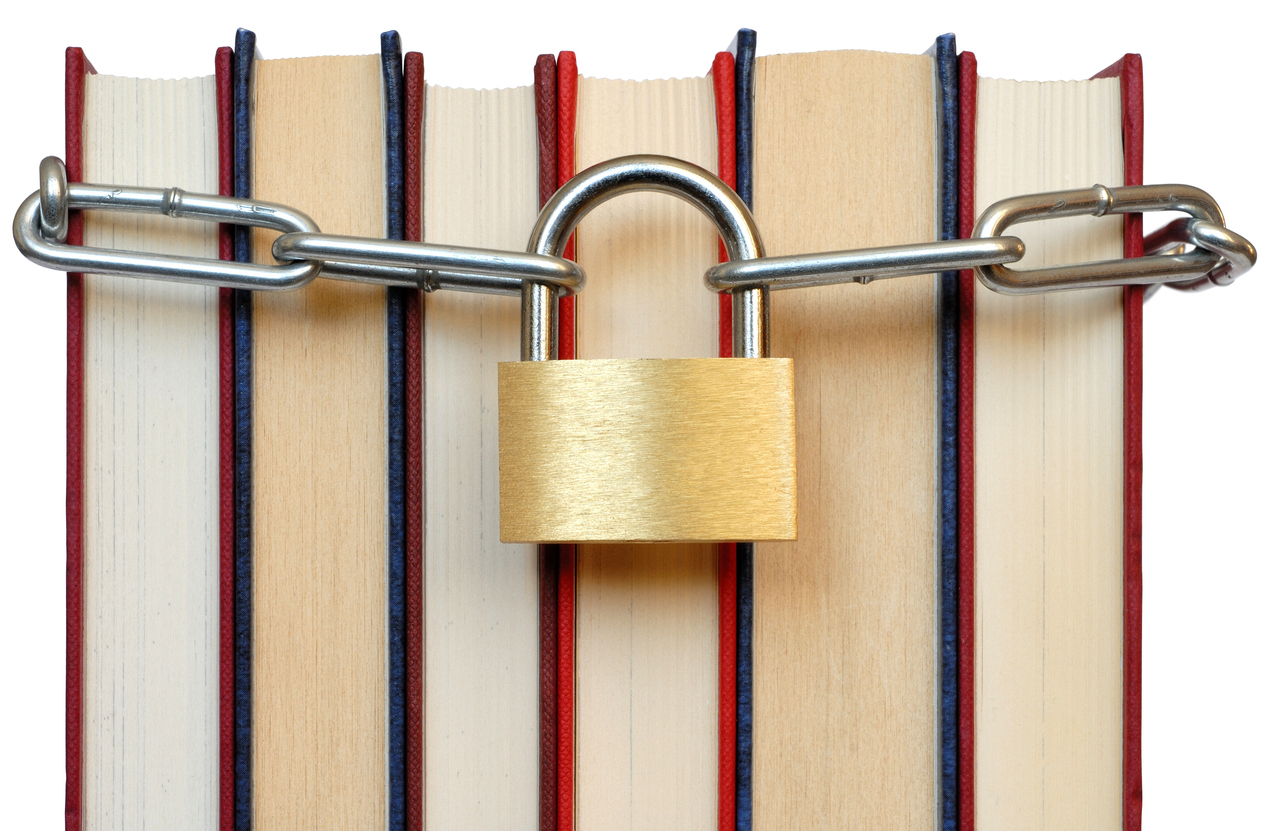

In March and April 2017, Ross Mounce’s blog listed a number of claims that certain scholarly journal publishers were letting some of their authors down. These were authors who had paid an Article Processing Charge (APC) to make their articles available free of charge under the Gold Open Access route. The claim was that these articles were still behind a paywall even though they should have been openly available. There is a paucity of further information on the topic. I am unsure when this problem was first identified, though this 2014 Techdirt piece, and the references cited therein, may be the earliest article to try to bring together examples.

I decided to investigate how common a problem this was. To do this, I began by referring to Paywallwatch, a web site specializing in identifying such cases. I also consulted with a few experts on the topic and put out a general appeal on Twitter in late April 2017 seeking examples of the problem – while also inviting people to retweet my request for information. I know that about 60 people retweeted my initial request, but do not know how many further retweets of the retweeting occurred. Nonetheless, I received virtually no responses to my Twitter appeal for information, and the responses I did receive (for which I’m grateful) led me to examples of which I was already aware. So I have had to rely on the few sources that specialize in the problem.

Mounce’s blog has repeatedly drawn attention to examples of such transgressions by publishers, and includes the somewhat startling claim that Elsevier had to refund $70,000 to people who had paid for access to articles when those articles should have been available for free. However, the 2014 Elsevier article by Chris Shillum and Alicia Wise to which Mounce refers only mentions 50 customers having to be refunded $4,000 in total, and it is unclear over what time period these refunds were made. The Elsevier article also explains some of the reasons for the problems arising.

Mounce has posed four pertinent questions in his blog to Elsevier – questions to which the company does not appear to have responded:

1.) Will Elsevier openly publish on a single web page, on a continuous, ongoing basis, the exact DOIs of all articles that Elsevier has been paid to make “hybridOA”, including the DOIs of articles that Elsevier were paid to make open access, that now reside at journals published by other publishers (if the journal was subsequently transferred to another publisher)?

2.) Will Elsevier refund 100% of the paid APC to each institution, funder, or individual that has a wrongly paywalled paid-for “open access” article behind a paywall?

3.) Will Elsevier hire and fully pay for an independent 3rd party forensic accounting firm to go through their pay-per-view and re-use licensing data/systems and records, including the period from January 1st 2005 until today (23rd February 2017), to produce a thorough openly available report on the extent of PPV payments AND re-use licensing payments for articles that should not have been sold to access, or to re-use?

4.) What meaningful assurances can Elsevier give that it will not make these mistakes again, given that it appears to be making these mistakes over and over again?

It’s not just Elsevier that Mounce has criticized; in his blog, he notes Oxford University Press as well, citing one specific journal article as an example.

In a similar vein, the Paywallwatch site has recorded instances, especially by Oxford University Press, Wiley and Elsevier, of such problems. Nonetheless, it is difficult to get a handle on how frequently such problems arise. The Paywallwatch site has 38 reports and comments on the issue, the most recent dated early April 2017. As this web site seems to have acted as a place for systematically collecting reports of these problems, could it be that no new problems have been unearthed in recent weeks? There may well be other reasons for the silence, of course.

Mounce makes a rough calculation of the likely financial gains by Elsevier through incorrectly paywalling articles that should be free, and makes a particularly telling point that the losers are not just those who incorrectly paid for access, but also the authors of the papers in question, as for a period of time their material was barred to non-subscribers when they should have been freely available, influencing other scholars and possibly earning citations as well.

Though some authors have tried to portray the matter as a plot by publishers to cheat the scholarly community, I agree with David Crotty that the problems no doubt represent errors rather than conspiracy. (Though I disagree with him that this matter can be dismissed as a “non-controversy.”)

What about publishers’ views? Dr Alicia Wise, of Elsevier, became aware of my request for information, and responded as follows:

We are looking into this, and you are right that actual errors are very rare. They occur from time to time for all sorts of different reasons, as is normal in any complex system. What complicates things enormously in this space is that one stakeholder can regard something as an error when other stakeholders do not, because there is not agreement or consensus. To give you an example, the Wellcome Trust view articles by their grant recipients as uncompliant if they are published with anything other than a CC-BY license. Our policy is to respect the fact that copyright is the authors, and to give them a choice of license. So who has made an error if an article is published without a CC-BY license? WT blames the publisher (which is a little weird as their beef is surely with their grant recipient; in our view the correct process was followed and the outcome is what it is). My sense is that your article could helpfully draw attention to the bewildering array of approaches, the utter lack of clarity of consensus, and the need for more pragmatic work by stakeholders to get aligned with the objective of making a system that works for all.

Wise is no doubt correct about the difficulty of keeping track of everyone’s conflicting standards as to what constitutes “real” OA, but the vagaries of OA definitions and mandate compliance are not at issue here; the question at hand is much simpler: how often does an author pay an APC to make their work freely available, only later to find that their work is behind a paywall? In other words, I want to know how often this occurs, and why. If the problem is not being caused deliberately, then is it caused by poor technical systems, by poor management practices, or by staff incompetence? Finally, I want to know how much of a priority publishers are giving to resolving the issues raised. At the moment I simply do not know.

My conclusions: the problem seems to be relatively small; the lack of any examples in response to my retweeted plea is a good indication of this. So let us assume that the number of incorrectly paywalled articles is a very small percentage of the total number of articles published by the major scholarly publishers. Nevertheless, each case represents a real problem. It is not only annoying to those who paid paywall fees, and to would-be readers; it is also frustrating and expensive for the publishers, who no doubt have to spend a lot of bureaucratic time and effort tracking down the cause of the problem and paying refunds when they receive a complaint from aggrieved customers. More importantly still, the issue causes considerable reputational damage to the major publishers, who are perceived, rightly in my view, as not giving the matter high priority, and who do not always provide ready answers to questions about how they are dealing with issue. In the first instance, the publishers should respond to the demands laid out by Mounce. His point number 3 is the really important one. The major scholarly publishers should ask independent consultants[1] to assess the problem, and make recommendations for improvement. However, for such work to be seen as credible by the outside world, the consultants must be given an open brief and must be allowed to publish their reports – as Open Access documents, of course!

[1] This is not a hint to ask me to do the consultancy; there are publishing consultants much better placed than I who could do the work.

Discussion

15 Thoughts on "Guest Post: Charles Oppenheim Asks How Big a Problem Are Articles that Should Be OA but End Up Behind Paywalls"

Interesting article. Though I tend to agree with David, I find your placing blame on the publisher and not equally, in light of Dr. Wise’s comment, ignoring the author rather strange.

I am not sure just how many scholarly articles have been published since the advent of OA, but I would think if there is to be an audit it should be of the entire industry not just (disclaimer: I have never worked for Elsevier) Elsevier.

From my vantage point as a production editor in academic publishing, I can assure that there appears to be no grand conspiracy to prevent OA, and that the reason for dropped OA lies perhaps more terrifyingly in simple entropy. Nearly all cases of missed OA that I’ve witnessed have been due to miscommunication between departments, or other human errors as mundane as failing to check off a box. I have yet to receive a cryptic email indicating I should “erroneously” publish behind a paywall. As Dr. Wise so astutely worded it, mistakes do happen in any industry. Production is usually the clearinghouse for OA articles and a pointed effort towards simplifying the process by publishers would help prevent errors in OA publication. Pragmatically, authors should also stay on top of their article’s progress at all steps of the production process, and not hesitate to contact their designated production editor if their article isn’t OA. It’s usually a simple fix.

Well said, JM. As an editor in scholarly publishing, I completely agree with you. I had one instance a few years ago where an OA article was incorrectly paywalled. It was the result of human error; the authors noticed it and informed me right away, and we had it fixed immediately. No grand conspiracy here! What I think perhaps deserves more attention is how quick publishers are to fix the problem. That wasn’t discussed in the article. Are we to assume that all of these examples are not only of OA articles being put behind paywalls, but also of the publisher then refusing to fix it? This would of course be a much bigger problem.

I think this is really the problem at hand, here (which speaks to a tome’s worth of other grievances that are outside of the scope of this comment). Factors which would theoretically prevent an author from having a problem addressed in a timely and satisfactory manner are systematic and far from limited to Open Access; an author may have just as much trouble, say, correcting a name, or amending a payment, if the publisher has not put in place a system to make it relatively simple for both employees and clients (authors/editors). It’s actually an issue of customer service, at its base. That said, it’s true that these OA errors can certainly waste valuable time in disseminating information and allowing for an article to be cited, even if it’s just mere days. Publishers should absolutely figure out a manner by which to fairly compensate authors in the event of this sort of error; from my end, I like the sound of this because it provides an impetus for these companies to make our lives (as employees) slightly easier, in order to prevent having to provide such recompense.

Thank you for your comments. As I made clear, I do NOT think the problems arise from malice, but rather errors by the publisher. I agree that publishers are generally prompt in correcting mistakes once their attention is drawn to them. I also made it clear, I hope, that this isn’t a rant against one publisher alone. Having said that, I would like to respond to a few points raised above:

1. It shouldn’t be down to the author to keep checking that their wish for OA has been respected; it is down to the publisher that they ensure they get it right first time.

2. I agree it is a matter of publisher customer service and reducing the complexity of the systems publishers use.

3. I stick to my view that certain publishers (and here I do focus on Elsevier) treat this as a matter of low priority. If anyone wants evidence, see the Twitter exchange between me (@CharlesOppenh) and Mr Gunn of Elsevier (@mrgunn), where he responded to my concerns with a sarcastic and patronising short video which trivialises the problem.

With regard to your first point, I agree entirely. I consider the author to be “the little guy” squaring up against behemoth publishers, and know just how hard it can be to try to register a (very deserved!) complaint as well as how impotent one can feel, waving a fist at an unmovable corporation. That said, I included “pragmatically” with the hopes of that sentiment being understood; regardless of how unjust it is to feel obligated to constantly keep a close eye on a service that you *paid for*, it’s the wisest move to avoid publication errors. I’d implore authors not to assume everything will go smoothly, and check on their OA once they receive notification of publication.

I should add that I very much like JM’s suggestion that publishers should routinely pay compensation to their authors for such errors.

Just have an anecdote to add: A number of years ago, a paper that I had published in a hybrid journal run by a very small association was published behind a paywall, though my organization had paid OA fees. I was annoyed to find that it had happened. The correction was made very quickly after I pointed it out to my editor. I chalked it up to being rather a rare occurrence, and never suspected a conspiracy. I think, though I do not know, that the error was made by the journal’s hosting platform.

Gold OA has been around long enough now that medium and larger publishers should certainly have put systems in place to prevent this sort of error, and to rapidly correct them when discovered. While it may not be the authors’ responsibility to check that a paper that should be open is open, many authors do check their published papers–for other reasons. As the party with the most vested interest in a paper’s publication, it should not be surprising that an author would catch an access problem. Of course, we have no way of knowing how many of these errors ARE caught by their publishers before final publication.

There is no conspiracy.

Re David Crotty’s comment on changing publishers. As far as I am aware, none of the examples of incorrect OA drawn to my attention was connected to a change of publisher. The problem is a combination of: over-complex systems; staff who do not understand said systems; and certain publishers putting too low a priority to resolving the first two problems.

Hi Charles, to clarify, the article that you cite above —

https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2015/03/13/more-creative-commons-confusion/ — discusses the journal Clinical Microbiology and Infection, which suffered problems with the display of OA articles when moving from Wiley to Elsevier.

Thanks for drawing my attention to that example, David. Readers interested in this topic might want to look at Graham Steel’s recent take on the matter – http://retractionwatch.com/2017/05/31/how-upset-should-we-get-when-articles-are-paywalled-by-mistake/

The Scientist has a piece on it today as well: http://www.the-scientist.com/?articles.view/articleNo/49544/title/Website-Flags-Wrongly-Paywalled-Papers/

An excellent and important discussion. Some might be interested in the content of this paper, of related topic.

Teixeira da Silva, J.A. (2015) Pay walled retraction notices. Bangladesh Journal of Bioethics 6(1): 27-39.

http://www.banglajol.info/index.php/BIOETHICS/article/view/24403

DOI: 10.3329/bioethics.v6i1.24403

One wonders how often the error goes the other way … that pieces that are supposed to be paywalled are accidentally made OA? Though I don’t think conspiracy is at play here, I do think that publishers could demonstrate that they are more attentive to these issues and taking them seriously. After all, if errors are made, they could also be losing revenue. So, what would assure me of taking it seriously is that there is as much attention to making sure OA contracts are implemented correctly as paywalls are.