The Public Library of Science (PLOS) reported a loss of 1.7 Million $US in 2016, according to their latest financial disclosure, which was released late last week.

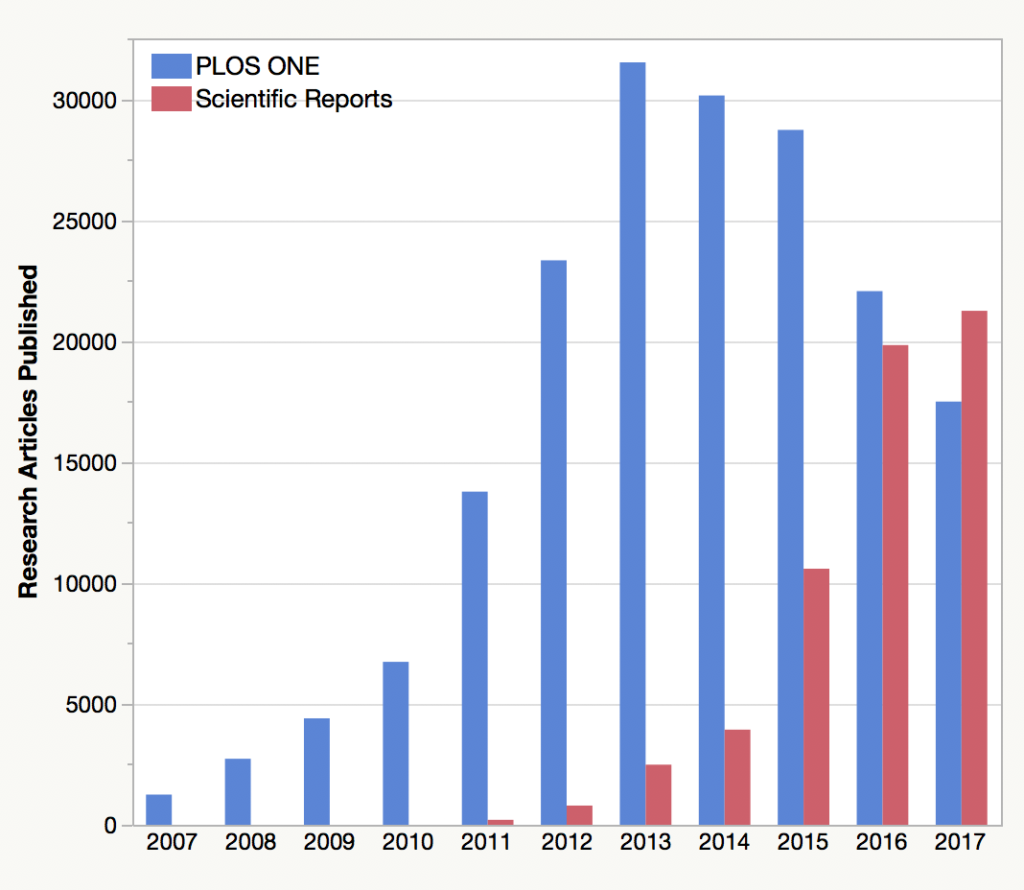

The loss for the San Francisco-based non-profit publisher was not unexpected. In 2015, the publisher barely broke even, netting around half a million US dollars after expenses, down from nearly $5 Million in 2014 and over $10 Million in 2013.

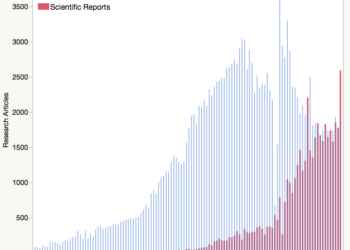

As PLOS relies almost entirely on article processing charges (APCs) for its revenue, a steep reduction of more than six-thousand research papers in PLOS ONE alone (Fig 1) deprived the publisher of a large portion of its annual revenue.

Chief Financial Officer, Richard Hewitt, explained PLOS’ loss in context of the overall success of the open access publication model:

The success of Open Access and increased competition in the publishing landscape brings inherent challenges for PLOS, including decreased submission and publication volumes, revenue and expenses.

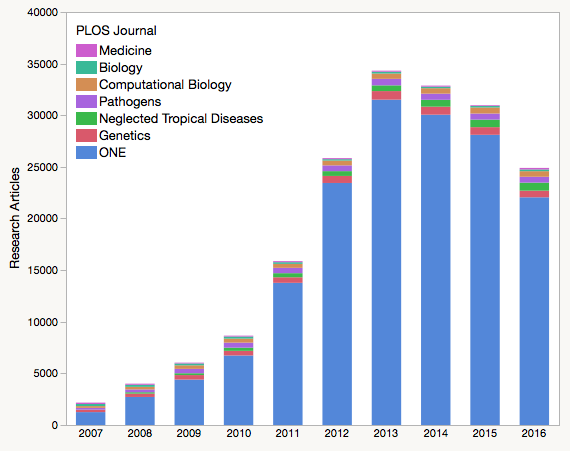

From the above figure, it should be very apparent that Hewitt is not talking about all PLOS journals. The financial success of the entire organization is built upon the surpluses derived from a single journal, PLOS ONE, designed to run cheaply and create huge surpluses through scale. In 2008, Declan Butler from Nature referred to PLOS ONE as their “cash cow.”

PLOS is not a financially diversified company. It is almost entirely dependent upon a single revenue model (the APC) from a single journal (PLOS ONE). This makes the publisher highly vulnerable to market changes and competition with larger, more diversified publishers.

Joerg Heber, PLOS ONE‘s Editor-in-Chief, attributed his journal’s shrinkage to a reduction in manuscript submissions along with a lower acceptance rate, which now stands around 50%. Journals that have implemented a similar editorial model are likely drawing manuscripts away from PLOS ONE, noted Heber in an interview with Retraction Watch last March. Earlier this year, Scientific Reports, which is published by Springer Nature, overtook PLOS ONE as the world’s largest megajournal. In the first ten months of 2017, Scientific Reports has already surpassed research article output from last year, while PLOS ONE is down by 7% (Fig 2).

PLOS is not a financially diversified company. It is almost entirely dependent upon a single revenue model (the APC) from a single journal (PLOS ONE). This makes the publisher highly vulnerable to market changes and competition with larger, more diversified publishers.

After several high surplus years, a relatively small 2016 deficit will not sink PLOS. However, the trend over the past five years does not look encouraging, and 2017 looks no better.

While I am not a financial analyst, there were other details in PLOS’ 2016 Financial Overview that were surprising. First, while PLOS continues to build its own submission platform (Aperta), only one of its smaller journals (PLOS Biology) is currently using it. More importantly, Hewitt writes that “the spending associated with this investment [Aperta] has been capitalized due to the multi-year nature of its anticipated future use,” which sounds like he was able to minimize the reported losses in 2016 by moving costs forward to future balance sheets.

Secondly, PLOS spent much more in salaries in 2016 (22M) than it did at its peak of 2013 (18M), despite publishing 27% fewer papers. This may reflect how easy it is was to hire staff when income was plentiful and how difficult it has become to shed them when money starts drying up.

PLOS continues to build its own bespoke submission and publishing platform, both of which have the potential to reduce longterm operating costs. In the meantime, the organization may have to start planning for a more diversified future that relies less on APCs from a single journal. Maybe it has already.

Discussion

22 Thoughts on "PLOS Reports $1.7M Loss In 2016"

Thank you for your continuing coverage of the megajournal marketplace, Phil, and PLoS One in particular. Your observations about PLoS (the parent company) and in particular its lack of diversification in having only a single major source of revenue are really important. I’m especially interested in why the PLoS One product plateaued and seems now to be struggling. Why is the first mover advantage, especially of a not for profit company’s flagship product, apparently so weak in the face of competition from the commercial sector for APC revenues generally and megajournal business in particular? PLoS seems to attribute this to the growth of open access generally, but shouldn’t a rising tide ordinarily lift all boats?

Interesting question! Both journals are very similar in structure, function, and price. Both are infinitely expandable. Last year, I attributed the competition being a matter of three factors:

Journal Impact Factor

Data Availability Policies

Publication Delay

Oh of course, yes. That was a very interesting piece also. You think those factors are still most relevant? Do you think that stronger “cascades” or other factors associated with being positioned in a larger diversified publishing house (or not) are beginning to have any effect as well?

For authors whose institutions reward them for publishing in journals with high Impact Factors, Scientific Reports’ score is nearly twice that of PLOS ONE. And if SpringerNature has a functioning manuscript cascade system, they would be more effective at keeping papers in-house. The fact that PLOS is just implementing their own cascade model (albeit late to the game), indicates that they’ve done their homework and would benefit from papers rejected from PLOS specialist titles. They don’t have many of them and they are not big, however, which makes me think that the net benefit is not going to be high.

A related factor here is SpringerNature’s incredible connections in the China market, which only helps their OA cascade strategy. This market’s sensitivity to impact factor is famous, and plays into their success. PLOS doesn’t have the same multi-pronged and long-term market presence in China, where more and more papers are coming from. Being first in line for these papers is a major advantage, one that Nature Publishing Group cultivated for decades, to the benefit now of SpringerNature.

I speculated in a comment to Phil’s original post (referenced above), that PLoS is still something of an unknown to researcher in many disciplinary areas outside of biology and medicine, and that perhaps “there are LOTS more people outside of medicine and biology who are more familiar with Springer than with PLoS and are more comfortable submitting to a mega-journal from a publisher with whom they have that greater familiarity.” So I think your comments about Scientific Reports “being positioned in a larger diversified publishing house” are probably on target, Roger.

Here in the social sciences, we can’t really publish in any of the PLoS titles and the biggest journal says “PLOS ONE features reports of original research from the natural sciences, medical research, engineering, as well as the related social sciences and humanities that will contribute to the base of scientific knowledge” . Only a few of my colleagues [we work society-environment topics] have had work published in PLoS 1 meeting these ‘contributing to science’ criteria. I have gone to Sage Open a couple of times instead, which does a fairly good job for a lower APC [$395]. Since we rarely have money for APCs above about $500 in my field and these fees often come from our salaries in the absence of any university money or grants, PLoS would have to offer us discounts [PLoS 1 is $1495]. It is really set up for people in the STEM disciplines, or at least those with a ‘big funding’ model.

Since PLoS depends on submissions and publication fees thereof, is there a change in the number of articles published in the traditional journals or changes in the revenue from the varied sources of that path?

As scientific author, I have actually chosen Plos ONE in the beginning, but was then discouraged when a paper was rejected for novelty (which should not have been a criterion). Furthermore, the informations for authors are now almost as complicated as for Nature/Science. I also do not like the lack of page proofs. (Note: I am on the editorial board of Scientific Reports).

This news brings to mind a few recent Scholarly Kitchen posts. The most obvious is Kent Anderson’s from last week, warning about the struggles one faces when one fails to diversify one’s revenue streams. Relying on a single point of failure can make for a fragile business:

https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2017/11/20/creating-safety-net-double-dipping-wrong-term-right-approach/

The other post that comes to mind is David Smith’s from 2014, about how over the long term those new entrants to a field that are initially seen as “disruptive” can often drop back as the incumbent players slowly adapt and maintain their hold:

https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2014/06/18/well-that-about-wraps-it-up-for-clayton-christensen/

PLOS has tried to diversify, and has consistently booked advertising revenues for many years. In 2016, they booked about $475K in advertising revenues. Without these, the loss reported here would have been more like $2.1M, assuming the advertising revenues came with few associated expenses. Other OA publishers have diversified with membership models, meetings, and co-development arrangements. PLOS’ Aperta development is likely a software diversification play. In any event, the point stands — diversification buffers risk.

‘the organization may have to start planning for a more diversified future that relies less on APCs from a single journal’ A single journal? Equivalent to something like 200 ‘regular’ journals across many scientific disciplines, PLOS ONE looks pretty diversified to me…

Has PLoS ONE, or anyone else, examined whether “predatory” journals may also be affecting PLoS ONE’s number of submissions?

One of the things that I find very interesting about this report is that while manuscript submissions have gone down in recent years, PLOS ONE’s acceptance rate has also gone down. I can only see two possible explanations for this: either PLOS ONE is increasing its selectivity even as the pool of proffered manuscripts is shrinking, or the quality of proffered manuscripts has fallen dramatically. Either of these scenarios would be kind of fascinating.

Alison Mudditt, is this something you can comment on?

PLOS ONE’s Impact Factor has declined monotonically for the last six years straight. If article citations are any indicator of quality, then the average quality of papers submitted to PLOS ONE has also declined. Since the scope of the journal and evaluation criteria have not changed, then a higher rejection rate may mean that PLOS ONE is attracting many more poorly researched (or written) manuscripts.

Plos received 13 million in grants which ended in 2011. Now 6 years later they are running in the red.

Is there business model sustainable?

As the new PLOS CEO, I’ve spent my first months assessing the organization and planning for a thriving future. I was attracted to PLOS because of its unique position pioneering multiple aspects of scientific communications and I believe this is what will carry us forward. And yes, there have clearly been many shifts in the dynamics of the OA market since PLOS was founded. Moving forward, we will be exploring what innovation means to us an organization and how we can collaborate and best lead within the expanding and evolving scientific communications ecosystem.

PLOS ONE remains strongly profitable, in spite of the recent declines in submissions. And the PLOS journal portfolio as a whole posted a profit in 2016.The $1.7M figure used above includes entirely planned technology spend from our investment fund. Our actual reported net loss was significantly lower at $854k (the difference is the unrealized net gains on investments).

The post rightly identifies some challenges for PLOS (and gold OA more widely) moving forward, many of which I identified in this recent Ask The Chefs piece. There are some fundamental business issues for us to address, including growth and diversification of revenue as well as our cost base. (And yes, those plans are already in development.)

I would disagree with Phil’s suggestion that the data policy has driven down submissions. In fact, PLOS has now posted more than 80,000 data availability statements providing a powerful demonstration of how PLOS’s assertive position on data is moving the needle to improve reproducibility, enhance discovery and provide full recognition of scientist’s work. The impact factor still plays a (frustratingly) key role, especially in certain markets, and PLOS continues to both advocate for and develop more effective metrics.

In response to the question about PLOS ONE editorial criteria, we have remained aligned with the principle of selecting robust, technically-solid science and are continuously fine-tuned to ensure that this bar is met.

Innovators who take big leaps are never one hundred percent successful. PLOS has been and will continue to be an organization willing to take risks in order to serve the scientific community. These risks sometimes come with a cost, but it is our goal to continue to learn from ourselves and the community we serve. That means an open dialogue in forums like these.

Thanks for the responses and clarifications, Alison! PLOS is lucky to have you.

Perhaps I am naive or just ignorant of accounting procedures. Can you explain what an unrealized net gain on investments are. Also, is the investments fund an off the books item and not reflected in your income statement?

In the fields I am active in, the quality of papers published in Scientific Reports is appalling, atrocious. Nature should be ashamed of themselves for corrupting science for pecuniary benefit. At some level they are surely aware of it, as they have chosen not to use the word “Nature” in the title to avoid hurting their brand-name.

However, people are wising up: Multiple “Scientific Reports” papers are now a red flag for us when we evaluate cvs.

Are the papers in PLOS ONE any better? Is your argument against Scientific Reports or against the Gold OA megajournals? BTW, why don’t you use your name when writing a comment?