[This post originated as a presentation for a NISO webinar on “Discovery: Where Researchers Begin.” Joelen Pastava, from Galter Health Sciences Library and Northwestern University and Robert Sebek, Collections Technology Specialist at Virginia Tech presented two very different, detailed, and absorbing looks at how users are accessing their library resources. My task was to offer a perspective on how I engage with libraries in the course of my research. I wanted to push the question from what it means for a humanities scholar when we use technologies and tools for discovery toward a humanities interpretation of discovery.]

There are plenty of discussions questioning premises and priorities in the entire scholarly communications lifecycle, and how epistemological bias can be related to or reinforce structural bias, from research subjects (why medical research still skews male) to library access (for unaffiliated scholars) to geographical privilege (per last week’s post on challenges for scholars in the Global South). Safiya Noble’s Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism is an important recent example of how knowledge that is presented as neutrally derived is anything but. (An interview with Noble for The Scholarly Kitchen about information and social justice, in two parts and in conjunction with her keynote at the SSP annual conference in June, can be read here and here.) Noble’s work has gotten a lot of well-deserved attention for pointing to the ways that technologies are created and operated by people, and people often have biases that seep into that work. It’s unlikely that a technology could be neutral or without bias, but part of the deep value in Noble’s work is the necessary reminder that we can’t and shouldn’t expect that it will be. Knowledge production — including search engines and search engine optimization — is a culturally informed act. And as such, we ought to be thinking hard about knowledge production at every stage.

What’s notable, to use the case of my field of early American and early modern Atlantic history, is three related ways that scholars are looking at libraries — and especially at special collections and archives — as a subject of study rather than a gateway.

The first is as institutions and collections with hierarchies of power and privilege baked in. Anyone influenced by Michael Foucault’s simultaneously complicated and nuanced, and yet quite basic observation that modern knowledge is an edifice created to look neutral and yet exercise a lot of power, isn’t surprised that institutions like libraries and archives are ripe for cultural analysis. But you don’t have to be a Foucaultian to appreciate that these key institutions were created in their modern, western form in the same era as nations states were extending their reach as empires. And alongside museums, they became imbued with extraordinary cultural value in ways that were useful to those political projects. I highly recommend James Delbourgo’s Collecting the World: Hans Sloane and the British Museum for a terrific analysis of how the museum became synonymous with a worldview with Europe (well, England) both at the apex and at the center of knowledge.

Two venerable institutions, key for historians of early America, have been the subject of thoughtful reflection on their extensive collections of materials created by Native American communities. Christine DeLucia took a close look at the history and ethics of Native American artifacts collected by the American Antiquarian Society (AAS) in the early to mid-nineteenth century. The AAS, recognized with a National Humanities Medal in 2013, is the preeminent library of pre-1876 printed, graphic and other materials, and most of its Native American items were shared or given to other institutions before the turn of the twentieth century. “Collecting,” DeLucia notes is usually “treated as a generative endeavor.” Yet when items arrived at AAS, and then when they were moved, they were usually entirely extracted from their original context, and from the knowledge of their communities of origin. A close examination of the accession (and deaccession) information, DeLucia points out, can regain some of this context especially when native scholars and tribal historians are part of that process.

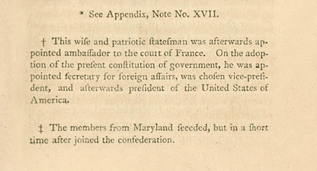

The second is as organizers of information, especially through cataloguing. The American Philosophical Society, founded in 1743, maintains an extraordinary collection of Native American materials. Earlier this year, they announced a completely new Indigenous Subject Guide, funded with a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, with a number of significant features. They have revised names used to describe indigenous languages and cultures in the collections, replacing old and often pejorative ones. They have not removed those entirely, but kept them as a record of the collecting history, “in order to reflect the history of how these terms were deployed.” The guide also elevates and recognizes the many indigenous knowledge producers who took part either in the past or the present in the creation of the materials. This is critical as often only donors or the researchers were associated with these materials, denigrating native knowledge and — again – reproducing some of the same hierarchies in the collecting and attribution.

The third way scholars of early America are approaching libraries and archives as subjects of research and investigation is by scrutiny of the way that materials themselves, not just the way they were organized and catalogued, reflected the interests and imperatives of those who produced them. How did the record books of the slave trade for example, participate in the act of erasing the humanity of the enslaved through detailing the cost and exchange of people in the same fashion as tobacco or coffee? How do these records then actually reproduce — in the archives — the violence of the slave trade? And how are scholars using those records without a conscious sense of their perspective – their bias — complicit in this reproduction of the violence? A prize-winning book by historian Marisa J. Fuentes is being read and discussed widely for the methodological sophistication and the depth of empathy she brings to these questions — focused on enslaved women in the British sugar colony of Barbados.

Historians of the early modern world have been thinking and writing about the information age of the 16th-19thcenturies — the period when print expanded so rapidly, but also when Europeans in the course of creating empires and new nations were creating huge volumes of records to document trade and other financial exchanges, politics, ideas, and more. The ways this information was produced had to do with technology (of paper, for example, and ink, and the times associated with travel that made recording information crucial for sharing across great distances) and the expansion of state power (through corporations, for example) and economies (associated with commodity production and with the violence of forcible migration of more than 12 million enslaved African men, women, and children). But historians are also interested in the forms of organization and classification and the ways that information became archived — and how those forms reflected the particular interests of those who produced the documents and the archives. A recent collection of essays, Archives and Information in the Early Modern World explores these questions through case studies such as the papers of the Star Chamber, the high court in England out of which legal precedents were being generated during the mid-seventeenth century Civil War. Who compiled these legal instruments, who had access to review them for their own cases? And what was the implication for those who did — and didn’t — have access?

Discovery is a fraught concept. As an intellectual and technical challenge for information science professionals it is complex for many of the reasons that the findings of my colleagues in the NISO webinar suggested. As a term of art in archival research it’s simply annoying when scholars “discover” something that generations of archivists have conserved and catalogued and made as accessible as possible. But just as we question the mechanisms for discovery, we can question the infrastructure of discovery in fruitful ways. Libraries are active producers of knowledge, not only providers of resources. Situating libraries within the longer history or even within shorter historical contexts of acquisition and organization helps reveal this role.

Discussion

1 Thought on "Libraries and Archives: A Humanities Take on Discovery"

I applaud Karin Wulf’s article for highlighting the potential institutional bias inherent in archives: the purposes for which they were formed, what material they collected or did not collect, how the material was organized and how it was catalogued. However, it is the researcher who determines the focus and direction of study, and he or she may bring scientific objectivity to the inquiry, and even opposition to the biases of the archive itself. Archival work tends to dissolve disciplinary bias. A focus on the documents may make an art historian aware of political, social, economic and familial aspects of the subject. The recent emphasis on electronic databases and search engines may inadvertently introduce bias, or at least move the inquiry a step away from the primary source documents themselves.