Today’s post is by Anita de Waard. Anita is Vice President Research Data Collaborations for Elsevier. This blog discusses her research in new forms of publishing, sponsored by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research, and is a writeup of her presentation at the EuroScience Open Forum held in Toulouse, this July.

To create better systems for knowledge extraction from scientific papers, it is useful to understand how humans glean knowledge from text in the first place. Studying the language of science delivers some surprising results: fairytale schemas help us to understand the narrative structure of articles; the study of verb tense reveals common linguistic patterns of sense-making between science and mythology, and tracing hedging in citations allows us how citations work to spread claims much like rumors.

Scientific Papers Are Written Like Fairytales

Ever since I joined Elsevier, in 1988, my colleagues and I worked on what we see to be one of the key roles of publishers: to improve scholarly communication through the use of information technologies. Over these thirty years, we’ve witnessed a series of hypes, and jumped on many bandwagons: some were much more successful than we ever imagined (er, like, the web….) some, we wisely invested time and effort in (like RDF and MarkLogic) and some, which we were gunning for, never lived up to their promise (we had high hopes for XLink and SVG as carriers for scientific content, for instance…).

The Semantic Web has been a particular interest since it started, and offered a tantalizing idea: surely, with ‘smart content’ and clever agents, we must be able to finally let go of the centuries-old narrative structure of scientific articles, and invent a format that allows computers to consume knowledge directly? And scientists won’t have to read and write all those (bloody) papers? More recently, we are told that Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Natural Language Processing will do all the reading and understanding for us: AI is going to eat the world’; Alexa will make publishers obsolete, and new software will deliver not just knowledge, but Facts. Surely, the time has come to finally bypass this narrative nonsense, once and for all?

In 2006, I received funding from the Dutch National Foundation for Scientific Research which allowed me to spend half of my time for four years to develop ‘a semantic structure for scientific papers’. And it turns out that when you sit down for it, it is actually very difficult to represent all the knowledge contained within a research paper in a structured, computer-legible format (I’ll challenge anyone to represent the full richness of the knowledge contained within a paper in a database entry, or triples, or acyclic directed graphs!)

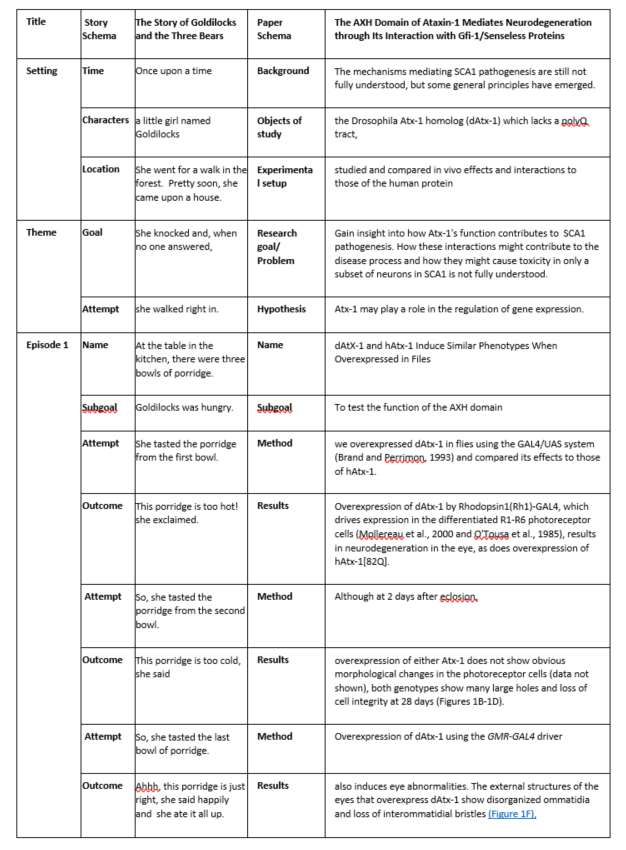

On the other hand, it is very easy to map a typical scientific paper to the schemas developed throughout the millennia for oratory or narrative text. Table 1 shows a snippet of a paper from Cell, mapped to the fairytale schema developed by Rumelhart in the 1970s, next to the fairy tale ‘Goldilocks’, mapped to this same schema. In both texts, we start with a Setting/Introduction, move to a series of Episodes/Experiments, and conclude with an Ending/Conclusion. Similarly, the IMRaD structure of a research paper closely follows rhetorical schemas such as those proposed by Aristotle and the Roman Orator Quintilian.

In stories and rhetoric, a statement exists not as a separate entity, but plays a role in the overarching narrative. It only makes sense to hear about what obstacles the hero is facing, once you know why she went on a quest, in the first place; likewise, reading a description of experimental conditions only makes sense if you know why the experiment was done in the first place. A paper has a narrative structure, because stories are how humans transmit (complex) knowledge. The narrative context provides the conditions within which the components of the story (or article) get their meaning.

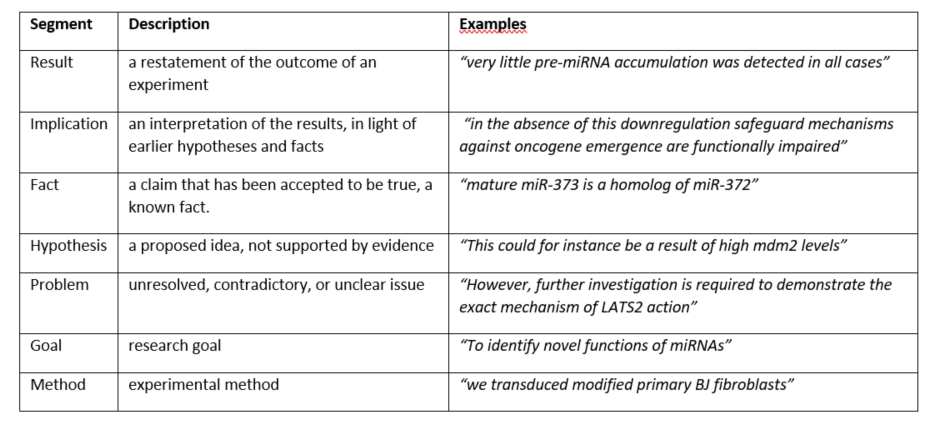

Scientific Facts are Explained Like Myths

But surely we can extract the facts from an article and use those, without any context? In research on so-called ‘fact extraction’ techniques, two very different types of statements are referred to as ‘facts’: first, experimental results (e.g., ‘After treatment A, half the samples had deteriorated’) and second, interpretations of those results (e.g., ‘X is a factor in Pathway Y’). In my research, I identified seven distinct clause types in biological text, including Result and Implication, which these two clauses would be classified as, respectively (see Table 2 for a summary of all seven types).

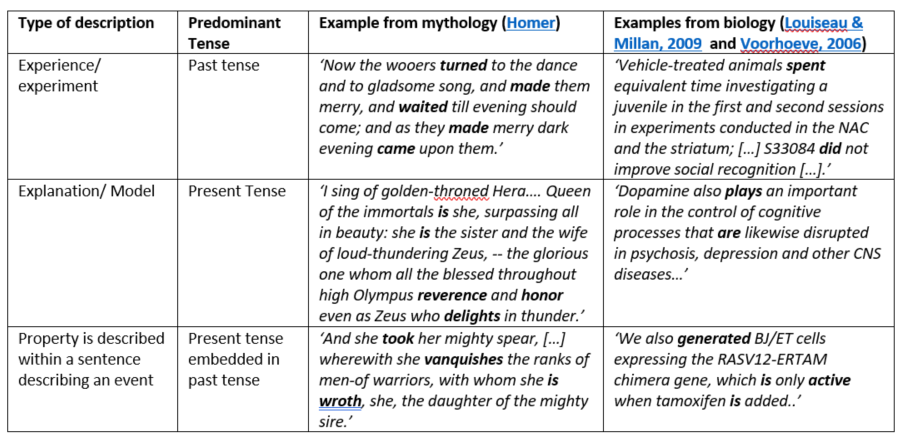

When we look at the linguistic properties of these different types of clauses, we find that they are generally written in one specific verb tense. In particular, experimental segments (such as Methods or Results) are usually given in the past tense, but interpretative statements about models (e.g., pathways or disease models) are generally written in the present tense. Authors regularly switch back and forth between tenses even within sentences¸ when referring to a model within a sentence that is largely about experimental outcomes. This connection is so strong, that changing the tense will lead readers will assume the clause type is different.

Interestingly, this is similar to the use of tense in mythological text: here, experiential discourse is most often provided in the past tense, while the mythological explanation for these experiences is written in the present tense. In cases where a further description of the reason for a human experience is needed, tense switches from clause to clause, exactly as it does in scientific text. In short, our tense use in experimental research articles mirrors that of mythological sense-making (see Table 3).

In summary: throughout the ages, our models for explaining phenomena have changed, from Greek Gods to cellular pathways, but how we speak about them has not.

Facts Are Shared Like Gossip

We find that scientific ‘facts’ are often described as an experimental outcome (a Result) followed by an explanation (an Implication). These two statements are often connected by a specific clause, of the form ‘Indicating that…’ or ‘These data suggest that…’ or ‘These results could imply…’, or ‘… possibly indicating…’. These connecting clauses take the form of a ‘pointing word’ (these, this result, these data) plus a hedged reporting verb (imply, suggest, indicate, etc.) or a reporting verb with a hedging phrase (possibly suggest, could imply, etc.). The author does not usually state that a given interpretation is correct: It is presented as an option, which might be true, or it might not be. In other words, Implications are given as hedged claims.

If we look at how these claims are cited, we find that in general, the hedging is lessened by a citing author. A corpus study of 50 cited papers with 10 citing papers each shows that ‘These results suggest that the APC is constitutively associated with the cyclin D1/CDK4 complex’ is cited as ‘…the anaphase promoting complex (APC) is responsible for the rapid degradation of cyclin D1 in cells irradiated with ionizing radiation [31]’: in other words, there is no suggestion and no reference to the experimental results. Similarly, ‘These data suggest that the RxxL destruction box in cyclin D1 is the major motif that renders cyclin D1 susceptible to degradation by IR’ was cited as ‘In the case of cell response to stress, cyclin D1 can be degraded through its binding to the anaphase-promoting complex…’, again omitting the data reference and the hedge. In the whole corpus, the hedging was weakened in about half the cases, without there being any suggestion that results outside of the cited paper were the reason for the greater confidence which a citing author gave.

In short, scientific facts are based on a game of telephone between cited and citing authors. Besides being pulled from its experimental context, claims are often validated (and turned into ‘known facts’) by the simple act of being cited (what Latour and Woolgar call ‘persuasion through literary inscription’).

So What Can We Do?

All these examples show that viewing papers as texts can help us understand how humans make sense of science. But can this insight also help build systems to support sensemaking? Absolutely. For once thing, these linguistic analyses can help set the direction for finding the key claims in papers. In the DARPA Big Mechanism project, the goal is ‘‘to develop technology to help humanity assemble its knowledge into causal, explanatory models of complicated systems”. Our group, lead by Ed Hovy at Carnegie Mellon, was able automatically classify discourse segments in these texts into seven categories, split the paper into separate experiments, and identify the individual type of assay for each experiment. That’s not quite the same as ‘mining facts’, perhaps: but it’s a start.

To improve the ability for readers to trace author’s claims, two further developments are key: first, current efforts to support the linking of methods and data to papers (such as the TOP Guidelines, the Scholix Framework for linking papers to data, and recent work on Enabling Fair Data) can greatly improve a reader’s ability to check the veracity of the author’s claims.

Second, it is important that we collectively work on better ways to cite these claims. Authoring tools that allow for a more fine-grained citation than that at the level of the paper, would allow the development of interfaces that show cited claims, within the context of the original paper. This would let the reader decide what level of certainty a cited claim deserves.

In short, we believe that understanding language can help us to build better systems for scientific knowledge transfer. It helps us to understand that scientific articles are not impartial observations or bags of computer-interpretable facts, but persuasive stories, written by and for humans. This proves, again, that the study of what humans do and how they do it (in other words: the Humanities) is needed, to develop better systems of scholarly communication.

Discussion

19 Thoughts on "Guest Post: Scientific Facts — Are they like Myths, Told through Fairytales and Spread by Gossip?"

I think a better model for understanding scientific and scholarly communications is the gossip model, which I walk through here: http://www.caldera-publishing.com/blog/2018/9/12/use-gossip-to-understand-scholarly-publishing.

Fairy tales aren’t evaluated on how likely they are to be true, while gossip is. Also, gossip is about news and updated information, while fairy tales can endure unchanged and without any necessary challenge for hundreds of years.

It is a good metaphor, but I don’t think this is an “either/or” situation. Humans are storytelling creatures. Much of the way we understand and interact with the world comes through our ability to tell stories about it. Yes, as noted above, there are elements in scientific communication that much resemble gossip (and the phenomenon described above, basically how one goes from “maybe” to “definitely” via the citation chain is extremely common). But that doesn’t mean that other storytelling methods do not come into play as well, as shown above. Fairy Tales are ways we impart important truths about the world to our children. So it’s not surprising that other attempts at communicating important truths also borrow from their well-established (and effective) structure.

Both, thanks for these comments! Truths are ‘told through stories’ throughout history: my main point is that scientific articles are not as diverged from these modes of knowledge transmission as many (mostly computer) scientists assume they are. David, you write “that doesn’t mean that other storytelling methods come into play as well” – was there a ‘not’ omitted there, perhaps? Kent: as I understand it (but I’m no expert), the ‘point’ of fairytales is often a moral/cultural one, rather than a knowledge representational one, so of course, the goals of fairytales and papers is very different: they are narrative vs. persuasive text genres. Elsewhere I’ve described papers as ‘Stories, that persuade with data’: perhaps that is a more satisfactory summary?

Fairy tales don’t impart many truths. Don’t trust old women living alone? Pumpkins turn into carriages? Princes redeem princesses? Princesses redeem beastly men? Are these “truths” fairy tales impart? Fairy tales structurally are narrative, and science can achieve a sustained narrative at times, but you could just as easily say that science and mysteries, or science and thrillers, or science and historical fiction are related.

I just think this is a charming if forced comparison, so it’s eye-catching and engaging. That’s nice. But I don’t think it’s correct — just like most fairy tales.

Sorry, I have to vehemently disagree. I will merely respond with this article and quotes from three great authors:

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/books/11243761/Neil-Gaiman-Disneys-Sleeping-Beauty.html

GK Chesterton: “Fairy tales are more than true – not because they tell us dragons exist but because they tell us dragons can be beaten.”

Angela Carter: ‘You see these fairy stories, these things that are sitting at the back of the nursery shelves? Actually, each one of them is a loaded gun. Each of them is a bomb. Watch: if you turn it right it will blow up.’

Neil Gaiman: “True and also lies!” says Gaiman. “If someone says: ‘We have investigated – there was no Snow White’, I’m not going to go: ‘Oh no, my story is now empty and meaningless’. The point about Snow White is that you can keep fighting. The point about Snow White is that even when those who are meant to love you put you in an intolerable situation, you can run away, you can make friends, you can cope. And that message,” he says with a smile of satisfaction, ” – that even when all is at its darkest, you can think your way out of trouble – is huge.”

At one time, for science, the standard was the reproducibility which, in today’s peer review world, becomes impractical, so trust, or, as Kent suggests, trusted gossip becomes the default standard until contrary results challenge the accepted, regardless of the semantic persiflage suggested. In fact, the latter can often mask the weakness or counterfactual materials published. This is an increasing problem in the current publish/perish environment for all the reasons which we can list.

At one time, there was the idea that early results might be published as letters or notes to share. Unfortunately, these now suffer the same fate as “journals” and require the standard formats.

I would suggest that Watson and offspring, including MarkLogic and, today, Shaping Tomorrow’s Athena can start to address the semantic issues defined in this article. But, for scientific research, the validation with the embalming removed still remains the standard and we are reduced to our trust in the “gossip” as Kent suggests.

The comparison with “Myths” is a false analogy since the stories as a message, moral or philosophical insight serve a significantly different purpose and need to be seen as a whole which gets lost in the attempt to parse truths by deconstructing the text. We are back to the cultural wars which came to a head with Sokal and others questioning “social text” as truth.

Hi Tom, I hope it was clear from the paper that the comparison with myths mostly focused on the linguistic details of the way in which insights are conveyed? I’m not stating that scientific facts are myths, just that the way in which authors use verb tense is similar to the way that tense is used in mythological reasoning (an earlier genre where people tried to explain the phenomena they observed): as such, it offers a peek into our modes of thinking, perhaps, as language often does.

“We are back to the cultural wars which came to a head with Sokal and others questioning “social text” as truth.” I am sorry, can you provide some references? Thanks,

Hi Anita

Through all my schooling, primary through Ph.D. and beyond, my humanities teachers were rather adamantine concerning the effective use and tense of verbs and sentence structure. And, academics used to pore over these nuances. As a hard scientist, journal editor and reviewer in the science literature, particularly today when many who publish in English, not their native tongue, this obsession with semantics seems, often, cast aside or is never carefully crafted and edited unless there are “qualifications” which are hedged in relation to the findings. One might want to study the academic journals in specific areas to see whether this correlation holds first within the disciplines and whether this makes a difference in the understanding of the research before one crosses disciplines and particularly when one crosses the science and the humanities and the various genres which is where journals such as Social Text and its editor, Andrew Ross, and the post modern authors ran up against the hard sciences (cf the writings of Sokal and Bricmont or Gross and Levitt, Latour and others. It would also be of interest in seeing the multiple presentation of the story of Goldilocks when translated across various ages and times, or the many scholarly translations of Shakespeare or even biblical texts where turn of phrase is critical. In reporting basic scientific research, I am doubtful that such semantic nuances are considered critical by the vetting community of specific journals. At least I have not seen such.

Regarding AI, or the emergent AGI, I have not found that this issue arises except in the social sciences or humanities where such nuances could “start wars”, metaphorically speaking. Perhaps this becomes of interest in the SF literature. You cite MarkLogic which was originally an early branch of the research that created Watson. The use of this AI engine to interpret text and even graphics as well as to construct simple reporting such as sporting events does not seem to be sensitive to the structures found in more carefully crafted literature. Shaping Tomorrow’s AI, Athena, in extracting foresight oriented materials across the literature, several daily scans in the hundred thousands would be an interesting set of data to search for semantic sensibilities.

Interesting post! As a creative writer working in the scholarly publishing field, I am always interested to see where the two types of writing overlap. One thing that I wonder about with this though is if perhaps the approach to this whole issue isn’t going the wrong way. It seems the initial thought process was to toy with the idea of restructuring papers to facilitate computer understanding to then transfer knowledge back to humans, but wouldn’t a more beneficial approach be to focus on how to improve human understanding in the first place? After all, you say, “But surely we can extract the facts from an article and use those, without any context?” (whether that’s tongue-in-cheek or not, I’m not sure) but anyone can tell you with stories both funny and tragic that context is always important, a fact that seems to be supported by your claims regarding statements within narrative structure and citations. And while I think a goal “to develop technology to help humanity assemble its knowledge into causal, explanatory models of complicated systems” is certainly laudable, I can’t help but wonder if something will be/is lost in avoiding that deep dive. I wonder if using this knowledge to make researchers more aware of how to write or read a paper well wouldn’t be a better use than using it to summarize via computer (not that you can’t do both of course, and I really like the idea of showing the citations in context!). Or perhaps the computer side is just the spring board to that deep dive and I didn’t clue in on that. In any case, I really enjoyed this article and learned a lot. Just throwing my two cents out there. Thank you for sharing and best wishes on your future work!

Hi Abby, thanks for your response! Few small responses: yes, the ‘surely’ sentence was intended to be ironic. I am mostly responding to activities in computer science/semantic technologies where many different attempts have been made to do ‘fact extraction’ from papers — there are many products created (and sold) on that basis, in the pharma industry, for example. “I wonder if using this knowledge to make researchers more aware of how to write or read a paper well” — that is a good point: my main goal was to help develop systems for reading, primarily, as opposed to writing, but it is an interesting idea to see to what degree this would help in writing as well.

Well, as David says above, it’s probably not either/or, but both/and. Communications go both ways after all. 😉 Again, great post. Super fascinating! Thank you for putting in all the work to figure it out!

Thank you for the interesting post! It reminds me of a book that I recommend to all those interested in this topic: “Ancient Mythology of Modern Science: A Mythologist Looks (Seriously) at Popular Science Writing” by Gregory Schrempp

Thanks so much, Robert, I’ve just downloaded the e-book version, looking forward to diving into it, looks extremely interesting!

Thanks for this really informative article, I love how you mapped the Cell paper to Rumelhart’s fairytale schema!

One of the things we are doing at Scholarcy is to exploit the linguistic conventions of academic writing to automatically highlight the key findings and claims made by a paper or report. The goal is to create a more condensed form of the article in real time, regardless of its format (particularly pertinent to PDF-only preprints).

Your point about how hedged claims often get cited as hard facts is important. One way of validating these citations – to check ‘did the paper really claim that’ – could be to employ techniques from automated question answering. By learning a function that maps the citation context to the automatically extracted claims made by the cited paper, it may be possible to link directly from the citation to the relevant part of the paper, saving the reader from having to both find and then search through the paper to figure out the citation themselves. This is an approach we are actively exploring at present.

Hi Phil, very interesting! Would love to hear more about your work, that’s exactly what I had in mind. We’ve done some work (which I briefly alluded to) with the Carnegie Mellon LTI as well, to identify core claims: let’s talk!

Hi Anita, happy to chat, drop me a line via scholarcy.com, cheers!

Hi Phil

You are on target regarding “hedged claims” vs “hard facts” or, at least results as reported. Today, in the pub/perish world, the need to get a publication out and accepted often over rides the idea of holding back to validate findings rather than hedging, often, obscurely, in print knowing that reviewers are unable, as way back in history, to verify in their own facility the results put forward in the article. This outweighs the grammatical “correctness” in the sentence and article structure which also lacks the concerns of authors crafting in the humanities. For the latter, it seems, as I said, that comparisons between reporting in the same area/journal become more valuable, particularly where there may be “hedging” where such can be more easily spotted. This need adds another level of complexity for humans and, thus, for AGI driven bots.

The issue in the current environment creates no penalty for the authors, but rather opens up to follow-on with subsequent “corrections” or options for others with counterfactual data not previously publishable. If your system is able to function as suggested, it is a screening tool for reviewers and possible ways to reduce the persiflage currently masking such problematics. In other words, submissions could be screened prior to being pushed thru the ever more crowded files on reviewers’ desks.