Editor’s Note: This is a guest post by Kent Anderson, founder of the “Scholarly Kitchen,” who is now publishing a subscription e-newsletter called, “The Geyser.” A version of this post was originally published on April 30, 2019. It has been adapted and updated.

The subscription model has been controversial ever since the Internet went mainstream in the late-1990s. Visions of free information permeated the culture. In scholarly publishing, so-called “Big Deals” have also been a source of friction. Various claims about the burden and effects of subscription expenditures have been made, with most claiming the costs are too high and ultimately unbearable. Some recent high-profile contract negotiations have been predicated on this idea, as have various policy proposals.

In March, I analyzed a set of subscription expenditures for about 900 public and private universities and colleges, working from data published in the Chronicle of Higher Education. My math showed that these academic libraries are devoting about 1/3 of their budgets to subscription purchases, with average cost per title of $23.48 for public universities and colleges, and $18.74 for private universities and colleges. Pooling the entire set, the average cost per title was about $21. My conclusion was:

Given the broader trends — emergence of China as a research powerhouse and absorbing the papers coming from there; organic growth in the US and EU STEM workforces; growth among higher education institutions; and general desirability around publication by more people — these cost data seem to suggest the subscription model is pretty efficient for institutions.

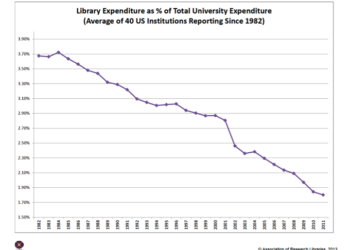

Some would disagree. The burden of the subscription model is one of the main assumptions behind the open access (OA) movement, after all. Now and again, subscription costs at academic libraries have also been blamed for the rising cost of tuition, fees, and attending university in general, despite evidence that overall spending on library budgets as a percentage of university budgets has been falling since the 1980s.

It’s true that the costs of attending college have risen dramatically over the past few decades, but there are many reasons for this — lower levels of government funding to offset tuition; greater demands from students and parents for campus amenities and services; more competition on multiple fronts leading to greater marketing and facilities costs; and, more administrative employees with good salaries and benefits to support all of the above.

Materials expenditures and salaries have been the main drivers of increases in library budgets. “Materials” is an imprecise word, however, and since I have yet to see an analysis of subscription costs as a percentage of university budgets, I decided to try to understand something about this aspect of the “materials budget.”

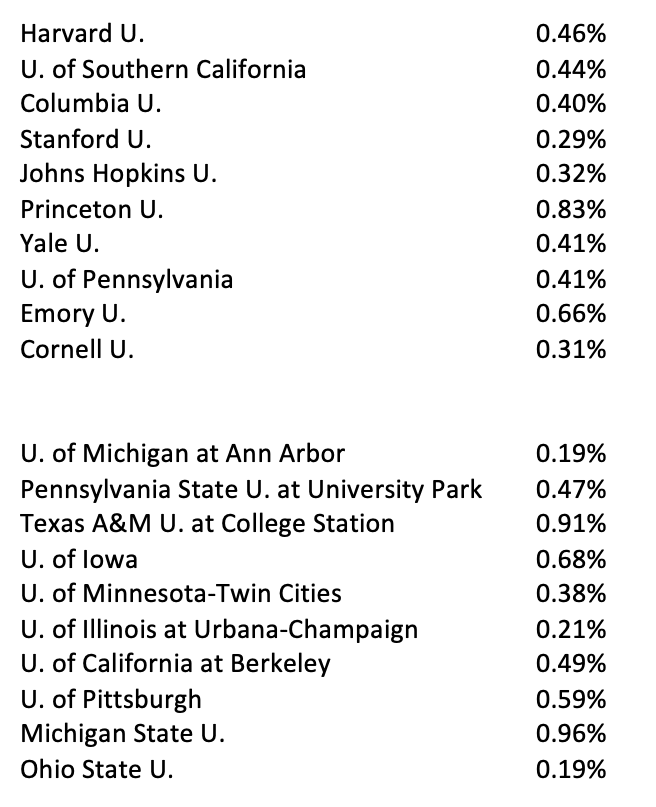

I supplemented the same data set from the Chronicle of Higher Education with the annual budgets for the 10 institutions spending the most on library materials in each list (private and public universities and colleges), the 10 spending the least in each, and the 10 spending closest to average per set (identifying the institution closest to the average expenditure level, and taking that school and those around it). This approach generated a sample of 60 institutions from the set of about 900.

What did I find?

For the sampling of public institutions, subscription costs amount to 0.41% of total institutional budget. For the sampling of private institutions, subscription costs amount to 0.59% of institutional expenses. Averaged, the two amount to 0.5% of the institutional budgets of these 60 institutions.

The institutions included by the approach described above ranged from Ivy League universities to state universities to private liberal arts colleges to medical colleges to technical colleges. It was a decent sampling of the space in that respect.

There were some highs and lows in the samples, of course.

For public institutions, the highest share of university budget applied to subscriptions was 1.40%. Among the sampled private colleges and universities, the highest share of overall budget appropriated to subscriptions was 1.56%. The lowest share of university expenditures appropriated to subscriptions for public and private institutions was 0.19% and 0.09%, respectively.

Here’s a table of the private and public institutions spending the most on subscriptions, and the resulting percentage this represents against overall budget:

To put these numbers in a more mundane context, at the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor it would cost each student paying advertised in-state undergraduate tuition ($13,856) only $26 per year to have access to all the subscription materials that institution carries. That means $13,830, or 99.81% of their tuition, goes elsewhere.

It’s worth emphasizing who uses all this information. Students. Faculty. Researchers. Scholars. Information and knowledge are core functions of any university, and 0.5% of the budget spent receiving the most cutting-edge and reliable research and scholarly publications seems like a pretty good use of funds.

This analysis appears to confirm one of the biggest benefits of the subscription or “reader pays” model — costs are spread across more participants in the market, making information or services more generally affordable. Models like author-pays Gold OA, which rely on payments from a smaller set of producers, centralize costs and profits (necessary) to a greater degree, increasing budgetary pressures for fewer market participants. Such models are far less scalable and more fragile.

In looking up the budgets for these 60 institutions, I was repeatedly surprised at how big the annual budgets are for these colleges and universities — from tens of millions of dollars for the smallest schools to hundreds of millions for the middle set to billions of dollars for those buying the most subscriptions. I wonder how many of us appreciate how university budgets have expanded over the past few decades. This perception gap is worth pondering further.

There are a number of limitations to this analysis. First, it relies upon sampling. I attempted to offset this limitation by taking three samples from each set, one representing the top, another the middle, and one for the bottom. Looking across these six sets, there wasn’t much difference once the percentages were calculated. Second, finding budgetary information for institutions introduced some inconsistencies of time periods, mostly in the sense that there are different fiscal years, different approaches to updating public sites, and so forth. So, in some cases the budget data is from 2017, while most is 2018 and some is 2019. Note that the Chronicle of Higher Education data was from 2016-2017. Third, nothing was adjusted for inflation, but this effect should be minimal as inflation has been low. Fourth, the budget numbers I entered were rounded to the closest million, which many were anyhow in budget documents, but this caused some minor (but to me, acceptable) imprecisions in some calculated percentages. After all, the message here is about the overall and general trend. If an institution wants a precise number for itself, it’s easy math. Fifth, it is limited to US institutions.

None of this is to say that library budgets aren’t under stress. However, it doesn’t look like subscription costs are stressing institutions themselves, and this discrepancy is worth pondering.

If subscription costs were a main driver of tuition increases and general affordability issues, you’d expect them to represent a major percentage of university expenditures. Based on this sampling analysis, they are not.

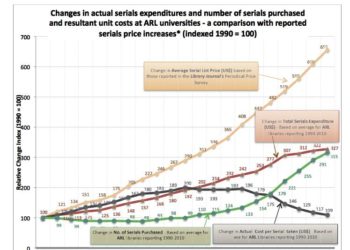

So why are libraries under stress if subscriptions aren’t the problem? I think that part of it is because the incredible growth in outputs over the past 20 years due to the entrance of China into the global scientific publishing economy, as well as organic growth in traditional markets, hasn’t been adequately appreciated by the powers that be. This stress is shared by libraries and publishers. According to the most recent “STM Report,” outputs have grown at 4% per year while publisher revenues have only grown at 2%. The rapid increase in outputs has been shown to be a main driver of cost increases for libraries and publishers.

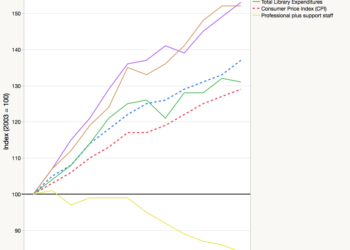

So why aren’t libraries supported adequately in this environment? As noted above, perceptions can become ossified. They certainly don’t self-update. There may be a perception that the world of the library is still the world administrators recall from their own university days. In addition, I’ll point to something Phil Davis wrote in 2016 analyzing ARL data around sources of expense in their libraries:

The problems affecting libraries and professors are the same problems affecting many other institutions that depend upon highly trained professionals — they cost a lot to recruit, train, and retain. And once in the organization, we like to reward these professionals based on experience and seniority. Unfortunately, these individuals don’t get any more productive as they age — a professor in 2016 is no more productive than a professor in 1966 — meaning that they get much more expensive over time. Unless we believe that we should index professors and librarians salaries to the CPI, we’re going to have to accept that professional costs are going to be difficult, if not impossible, to contain.

Davis also suggested a reason why it’s easier to scapegoat publishers than to look at other, closer, and more uncomfortable contributors to the trends:

Library materials represent a tiny percent of overall institutional expenditures. An outsider may be surprised at how much fuss is made over such a small slice of the institution’s pie. But libraries are still perceived as a core function of the institution, standing as beloved architectural statements of their historic value. Perhaps this is why no one wishes to take responsibility, at least in part, for their financial neglect.

Library expenses are complex. Publishers and libraries are both dealing with a volume of papers that has grown with the rise of China, with increased funding, with greater publish-or-perish pressures across more fields, and with the general growth of the scientific disciplines.

It’s worthwhile to pull back and look at the big picture. Rather than blaming publishers for budget woes as they themselves deal with unprecedented volumes of submissions, higher technology and wage costs, and greater marketing and infrastructure demands, these data to me hint that we might want to celebrate the fact that such vast amounts of knowledge are so affordable. From these data, it looks like site licenses are raindrops in the rivers of institutional spending.

It’s actually pretty amazing that thousands of students at colleges and universities — as well as instructors and researchers — can in most cases get access to much of the world’s developing knowledge for less than a penny on every dollar spent by institutions of higher learning. Subscriptions aren’t a problem. They’re an accomplishment of efficiency and practicality.

Discussion

41 Thoughts on "Guest Post: The Surprisingly Low Burden of Subscriptions at Institutions"

This sounds about right. For all the fuss from the University of California, the California Digital Library spends $11m a year on Elsevier content, compared with a library budget of over $300m and a total University of California budget of over $32bn. University of California researchers download 11m articles a year from Elsevier’s ScienceDirect. For the sake of transparency, I work for Elsevier’s parent company.

Can you back out salaries and building costs from that$300M budget so we can get a better sense of the proportion of “information” money going to Elsevier?

You can find the figures for 2019/20 here: https://www.ucop.edu/operating-budget/_files/rbudget/2019-20-budget-detail.pdf page 101; and for 2018-19 here: https://www.ucop.edu/operating-budget/_files/rbudget/2018-19budgetforcurrentoperations.pdf page . If I have understood the data correctly. 40% of the budget is spent on collections and materials ($117.6m) and the Elsevier contract is about $11m (9.4% of collections and materials and 3.7% of library budget). The UC library system provided 37m downloads in 2017. In 2018, Elsevier provided 11m downloads ( I don’t have the 2017 numbers), so Elsevier provides about 30% of all the UC the downloads. Elsevier publishes about 18% of global research, which suggests UC faculty, researchers and students find it pretty useful.

What years were used by the patrons in that 37m downloads? Any backfile content that was paid for in previous years? Were they counting both HTML and PDF (the new COUNTER unique stat is going to hit Elsevier particularly hard.)? Is the 30% of all downloads counting “specialty” Elsevier titles that aren’t included in the big deal? Is the 30% of all downloads counting Gold OA?

Mixing together salary data and materials data in a study of library expenses is going to produce irrational results. My own library also spends about 2/3 of the “library budget” on salaries, and about 90% of the rest on subscriptions. But it’s important to understand that library directors/deans don’t see that as one single budget within which to make tradeoffs. The salary portion is non-discretionary, set by HR policies and collective bargaining agreements (I’m in Canada), and that “pot” of money is completely disconnected from the materials budget.

That said, I’ve never heard anyone making the claim that subscription costs are budget breakers for the entire institution, just for the libraries. So claiming to refute that is what is commonly called a “straw man” argument. Yes, institutions should be putting a higher percentage of their operating budget into the library materials budget. In fact, a much easier study you could have done would be to report how the library materials budget as a percentage of the university operating budget has decreased over the last 20+ years, which it absolutely has from the studies I’ve seen. But that is a separate issue from how within the materials budget, the subscription costs have gone up far faster than inflation, while the profits of the commercial publishers are enormous by the standards of almost any industry and have been impervious to market “control”. I have trouble blaming the taxpayers who fund the public universities for not wanting to pay for those profits.

“My own library also spends about 2/3 of the “library budget” on salaries, and about 90% of the rest on subscriptions.”

Are you sure? That leaves only 3% for purchases, facilities, IT, and all else.

That is not exactly how university budgets work, is it? For that matter even in business facilities and IT are not usually charged back and in any meaningful way part of a units budget.

And for purchases, yes, exactly, that is the point

For many libraries, this isn’t far off the mark. People + collections has been well north of 90% at the libraries I’ve worked. However, note that for many institutions, the library budget doesn’t include rent, utilities, HR, IT, finance, and many other expenses which are absorbed by the institution. In Kent’s example below, he says the library only receives 1% of UPEI’s annual spend – but the figure he is looking at for the library budget almost certainly doesn’t include many of the expenses I list above.

Sadly, yes, I am sure. Of course, facilities like electricity, heat, and water don’t come out of the library budget at all, nor does IT network infrastructure, but staff computers do, as well as furniture, stationery supplies, etc. I make a point of getting as many stationery supplies as I can for free from vendors when I go to library conferences.

According to the budget for your institution (http://files.upei.ca/finance/operating_budget_2018-2019.pdf), the library only receives 1% of the UPEI’s $120 million current annual spend. If 90% of 1/3 of that is spent on subscriptions, then UPEI is spending about 0.36% of its overall budget on subscriptions. This would put it on the low end of the sample described here.

Actually you misread that. The budget you cite refers specifically to “library materials” in one place and “library books and journals” in another. That document doesn’t include/break out staff salaries for the library. What you might find interesting for data from Canada is the MacLean’s annual University Rankings issue. They break down in separate tables (in the print issue, haven’t found it yet on their website) the percent of univ budget spent on the library overall, and a different table that shows percent of library budget (which includes salaries) spent on books/journals. I think their data may come from CARL, the Canadian version of ARL, and whose annual survey is the Canadian academic library version of IPEDS data in the US: http://www.carl-abrc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/CARL-ABRC_Stats_Pub_2016-17-V2.pdf

Mr. Anderson has spent a great deal of effort in justifying something: either the relatively low cost of “Big Deals” within the global university budget, or the percentage of operating budgets that libraries receive from their parent institutions, or the percentage spent on salaries versus acquisitions in the library allocations. These trains have all left the station. The point that we need to focus on is not these carefully constructed analyses and justifications but rather whether there is better way of doing business: thoughtful librarians and faculty are thinking about whether there may be a better, even less expensive way of improving access to scholarly information. Let us focus on this question!

In focusing on your question of thoughtful ways to have better, less expensive ways of improving access to scholarly communication I have come up with the following ideas: (1) societies can rediscover university presses and partner with them instead of partnering with the large commercial publishers, (2) commercial publishers can pay back “staff time” to the taxpayers for all work related to peer review, authorship, editing, etc. by sending a credit memo to all subscribers based on their own faculty and staff work every year, (3) any aggregate data collected and sold by commercial publishers should be applied to a credit to each library depending on their usage because the more usage the more valuable this is for third parties , (4) any library willing to “host” the journals on their own servers should be given an extremely large credit for not costing the publishers server costs, (5) if you can’t move to OA on a particular journal immediately then give a 5-year plan to move to OA for that journal.

Is any of this relevant?

ALL librarians I have spoken to on three continents complain about Big Deal costs versus their budge allocations. Also if you attend any radical publishing event, as I have done, it is pretty clear that the ‘big 5’ publishers are not at the forefront of innovation, they are not well liked (especially given CEO salaries and labour conditions in the branch offices), and if you put, say, 50 writers, hackers and humanities scholars in a room they can do something way more interesting and give it out for free. Here is an example from Coventry University. http://radicaloa.disruptivemedia.org.uk/pamphlets/ [yes I know, it is not really free,..].

Comparing costs of journals to total university costs is not very informative. And comparing costs of journals to total library budgets is also minimally informative when, as a previous commentor noted, most of a library budget is staff which is not really a substitutable good for journals.

The reality is that the amount of money (in absolute terms) universities spend on journals has grown at a rate much faster than inflation. In fact at 5x the rate of inflation (according to data from American Research Librarians statistical summary 2004-2005 and 2010-2011). You can game this by looking at “effective cost per journal” and it doesn’t look as bad, but that assumes that libraries want to buy every journal forced on them by bundling. They don’t. Nobody has time nor desire to read the exponentially growing literature. And libraries definitely had efficiencies when they could pick and choose journals in subject areas that matched their own strengths and interests on campus.

The burden of journal prices is both increasing and problematic.

This. If you wish to compare things, compare the cost of journal subscriptions versus what is paid to each faculty member for publishing services not including their salary, benefits, etc.

The data you cite (ARL statistical summaries) have been debunked as misleading, based on print costs and not on digital costs. See: https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2016/03/10/revisiting-have-journal-prices-really-increased-much-in-the-digital-age/.

The problem everyone faces is a rapid increase in outputs from an economy (China) that exports more research than it pays for. That, and the fact that digital is actually more expensive than print.

“Have been debunked” = you wrote a blog post arguing for a per provided article basis.

I already made it clear I personally find the per provided article basis misleading. Price per desired article is a much more relevant metric, but that is of course hard to assess. Total absolute costs is a raw number with no funny business going on and the closest I can get to what I want. My statement about total absolute costs increasing at a rate much faster than inflation is accurate.

And really – the growing publications from China argument is not very convincing. The real reality is that everybody is publishing more because its a rat race. And an increasing fraction of what is published is not worth (or at least not required) reading.

“Have been debunked” means that serious errors in the meaning, interpretation, relevance, and sourcing of the ALA Serials data were found.

Journals are now larger, and there are more of them, precisely because China went from a marginal contributor of scientific outputs to the top producer. The costs of review, revision, publication, and maintenance all increased because of this. If you look at the chart in the link I shared, you will see that nearly all of the cost increases are attributable to increases in the volume of publications.

I’m curious about the costs of review, revision, publication, and maintenance. I’ve heard several big commercial publishers say they are able to have fewer editorial staff work on a larger number of journals (especially the non-marquee journals) due to more automated methods of submission and review.

If one thinks subscriptions are costly, just wait for the cost of publishing books hits the library budgets!

I think a more accurate title for this piece would have been “The Surprisingly Low Percentage of Overall Institutional Spending Represented by the Large and Growing Burden of Subscriptions for Academic Libraries,” but (as is so often the case), what that title would have gained in accuracy it would have lost in concision.

So, to make it really concise, let’s call it “Unsuprising, but Still Shocking Burden of Subscriptions.”

That version would represent a gain in concision, but a loss in accuracy. 🙂

Well, I wrote a post below the headline. I hope all those words didn’t go unnoticed. Lots of nuance, and even some links to other posts that are more informative than a headline.

K. Anderson states that “The burden of the subscription model is one of the main assumptions behind the open access (OA) movement.” This is not true, even though this argument did surface, particularly in library circles. The main assumption behind the OA movement was that certified knowledge should be totally accessible to all, especially when funded by public money. It was a matter of principles, not money. A subscription model simply does not cut it if the principle of total accessibility is central, and that is quite obvious.

The argument about libraries not receiving enough money is quite old. The train, it could be said, has long left the station. If the large commercial publishers did not do everything possible to maintain their profit rates at the level where it has been for a long time, libraries might also have a better time of it. Should library budgets follow the rate of growth of publisher greed? This would be a curious way to organize any budget: acting on the basis of “Gentlemen, please tell us how much profit you want, and we will do our best to find the money…” is simply ludicrous.

As for the growth of scientific publications, the “publish or perish” philosophy added to the obsession for rankings are much better ways to explain this phenomenon than the rise of China in research publications. While not perfect, the following book does provide some useful evidence: Imad A. Moosa, Publish or Perish: Perceived Benefits versus Unintended Consequences (Cheltenham, UK Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2018). Incidentally, the cry to raise library budgets was long supported by commercial publishers in public forums, and they did so well before anyone thought of mentioning China as the culprit. Of course, nowadays, taking China as a universal scapegoat has become a favourite game in North America and particularly in the USA.

‘acting on the basis of “Gentlemen, please tell us how much profit you want, and we will do our best to find the money…” is simply ludicrous’ – yes, this! It is ludicrous, and yet it is a perfect summary of how our entire “industry” actually works! And the answer to why librarians and universities participate in a ludicrous system is: “we have no choice thanks to the unregulated monopoly power granted to copyright holders”.

Copyright is an ownership right. It is temporary. It is not a monopoly power.

Also, with cultural strictures on duplicate publication, copyright is merely reinforcing the norms of scholarship.

See: https://thegeyser.substack.com/p/bonus-monopoly-copyright-or-culture

I’m sorry but if you talk to an economist, you’ll find that intellectual property rights indeed are considered monopolies enforced by government. Since the concept of “monopoly” is an economics term, I think it’s appropriate to accept their definition.

Noted economist Dean Baker writes about this issue frequently, eg. http://cepr.net/images/stories/reports/ip-2018-10.pdf although he’s more often focused on software and drug patents in his analysis of the economic impact of this monopoly power.

If you prefer a scholarly article, there is this one: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3324194?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents

The only people I find arguing that copyright is NOT a monopoly are representatives of the commercial publishers.

Copyright in an individual work is a monopoly. It’s a different question whether the publishers of such works constitute a monopoly, as they compete furiously with each other.

Yet, as an ownership right, copyright can be transferred. It is a limited monopoly (fair use limits it, time limits it, etc.), and it can be transferred. It is not a “monopoly power,” as you wrote. Every copyright transfer is negotiated with publishers, and often the rights are not wholly transferred but shared. I think we need to just move on from talking about copyright as a monopoly, because that’s really just silly at the end of the day. It’s like saying I have a monopoly power over the meal I just cooked. Well, I can share it, give you a taste, keep it for myself, sell it to you, or let you have the whole thing. Am I a monopolist cook if I do any of these things?

There is also the fact that academic culture frowns severely on plagiarism and duplicate publication. What relevant and useful rights within copyright are actually denied in the academic setting?

China is not being scapegoated, but described. It is now the #1 producer of scientific papers, yet the journals economy is largely supported by institutions outside of China. Also, calls to increase funding for scientific research have been heeded in many countries, increasing outputs. Overall, we have a mental model of outputs and volume that is sorely outdated, and needs to look about 2x as large as it once was.

My point was that publishers were characterizing the growth of library acquisition budgets as “too slow” well before China began coming into the picture. And the main driver behind the growth of publishing is the “publish or perish” mentality, not China. Moosa, whom I cited, mentions several consequences, the best known among which is so-called “salami publishing”.

These positions are not mutually exclusive. Publishers have seen an enormous growth in the number of papers from China. And the pressure to publish has long been a factor. No reason to argue about things we agree on. For my part, more discriminating publishing would be a good thing. That would mean higher rejection rates and fewer publishing venues. This would rid of us of salami publishing, as it is quaintly known. I think there is no chance that this will come about.

Couple of items. It would have been helpful to see the data from academic libraries at comprehensive universities like the California State University system. Also the per journal data assume that all journals are created equal. So, yes the per journal cost is fine but if faculty use only a fraction of the journals the analysis is different. At CSU Fullerton the acquisitions budget runs about 1/3 of our total budget and Elsevier alone is about 15% of that total.

Well, that makes sense, as Elsevier publishes about 17% of all articles in journals.

I would like to see an evaluation like that to libraries in South America or Africa institutions. We might have another view of Plan-S.

I am certain that it is all relative to the Library, the Institution, and the overall support or lack thereof in sustaining subscriptions.

I am at a Research University that is small but quite advanced and cutting edge. It is imperative to support both the student outcomes and the research outcomes… and the subscriptions are the largest part of my budget, over 2/3rds of it. We work on it, and continually attempt to improve the subscription offerings. But the realities of keeping high standards does get expensive, relatively speaking.

New iphone releases keep increasing in price and you may say that each iteration offers new functionality and access to new data. My electricity, fuel and broadband services increase in cost every year with no additional features or benefits. Why is everyone (generally) willing to pay for iphones and these other services with rising costs (usually always above inflation) and not something so fundamental as scholarly knowledge – which also has increasing costs for many of the same reasons as libraries – including technology (you can access research on your iphone!). Openness can be achieved via the Springer nature model of SharedIT or a number of other sharing models.

I don’t think you can judge value based on cost per title in a “big deal”. If my TV subscription has 45 channels and I only watch 3, am I getting good value? I think usage is the larger issue.