When you stand on a fault line, even the slightest tremor raises the specter that the entire edifice may collapse beneath your feet.

Knowledge Unlatched (KU) is back in the news. Founded as a not-for-profit open access (OA) book publisher by Dr. Frances Pinter, the organization has gone through a couple iterations until re-emerging as a for-profit company headed by Dr. Sven Fund. (Despite its for-profit status, KU continues to use its old URL, with a .org domain.) KU is now hard at work on developing its program, including its business model. A major piece of this, recently announced in an interview by Fund, is the Open Research Library (ORL), which aims to be a comprehensive collection of all OA books, of which there are now (according to KU) about 15,000-20,000, with approximately 4,000 more being added every year. KU can aggregate all these books, which have many publishers, because of the terms of their Creative Commons (CC) licenses, which encourage reuse and sharing. And that is what has set off a seismic disturbance.

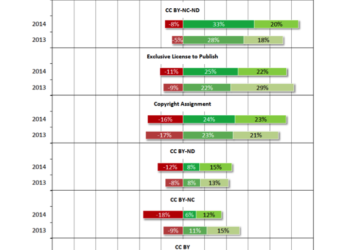

I wonder if some of the people who use these licenses have actually thought through their implications. The entire point of the CC BY license, which is preferred by many OA advocates, is to let anyone do anything they like with the licensed content as long as they provide proper attribution. Permitted uses include aggregating content for commercial purposes. If publishers do not wish to authorize aggregations and commercial reuse, they can issue a CC BY-NC-ND license (the “NC” and “ND” are for “no commercial” and “no derivative” respectively). In other words, OA publishers have at their disposal CC licensing options that would prevent precisely the kind of aggregation announced by KU.

To judge from some of the comments inspired by the announcement of ORL, however, the whole business of OA publishing and the use of CC licenses should be brought before the community of OA publishers before proceeding. Apparently there is, or there is supposed to be, an unspoken and uncontracted agreement not to act unilaterally. But that is, in fact, contrary to the license under which the works in question were licensed. The very basis on which CC was conceived in the first place was to eliminate the administrative burden of seeking copyright permission (because the licenses tell you what you are permitted to do without asking). Nothing in the licenses requires or even suggests that the re-user should notify the originating author or publisher of intended use in advance.

Here are a couple examples of the comments. Let’s start with a Twitter thread from @punctumbooks, an increasingly prominent OA publisher. The argument here is that KU is not behaving like a “real” OA publisher and that its ORL project is not endorsed by Punctum. Punctum is displeased that KU is building such an aggregation without first consulting the “community,” even though it is within its rights to do so. In Punctum’s words:

“All OA books have licenses that allow sharing, so KU has done nothing wrong (legally) in aggregating books on its new @OpenResearchLib platform.”

But what KU violates, according to Punctum, is the spirit of OA publishing and the community of OA publishers, for which Punctum apparently is a spokesperson:

“What the community partners have in common (in addition to valuing diversity = ‘one size will never fit all’) is a commitment to #OpenSource tools & infrastructures for OA books & to sharing expertise & resources and returning the ‘knowledge economy’ back to the public domain.”

Whenever someone invokes the spirit of an arrangement, the proper response is to ask: Did you get that in writing?

It is not only small organizations like Punctum, however, that feel this way. Here is Springer Nature on ORL:

“Recently, a new hosting platform, the Open Research Library, was beta launched by Knowledge Unlatched. This is not something we were informed or consulted about even though content from our SpringerOpen imprint was incorporated. While we have not asked Knowledge Unlatched to remove our books, and do not intend to do so, we have not endorsed the platform as a partner. We continue to review community partnerships and to advocate for the best experience for authors and readers in making OA books available as widely as possible without restriction. We believe that the development of community resources for open access books is best achieved through open consultation with the community, and would advocate this approach in future for all those involved in OA books.”

Springer Nature explicitly says that they support the use of the CC BY licenses, so why complain that ORL “is not something we were informed or consulted about”? Surely a hugely successful enterprise like Springer Nature knows that the first rule of business is read the contract.

The protest against KU’s actions have even prompted condemnation from OPERAS (Open Access in the European Research Area through Scholarly communication), which derides KU for not conforming to the principles of open infrastructure:

Based on the statement from KU and the early release of the ORL, the approach of this platform closely resembles well-known internet strategies to quickly achieve a dominant position by aggregating all available content and offering a free service to the community, while aiming for a lock-in of users and stakeholders. The ORL is neither open nor transparent, in particular regarding its governance.

OPERAS favors distributed infrastructure. So does Google, as its search engine then becomes the point of aggregation. Google is the autocrat of the open Web. Consolidation and concentration are inherent properties of media in a networked environment.

For its part, KU believes it is doing god’s work; the company’s tag line is “Making open access work.” In the spirit of transparency it released its most recent financial data, though it was under no obligation to do so. The figures reveal that KU had in 2018 revenue of $2,206.695.78 and a profit of $51,977.51, which suggests that this is a pretty small business. But it has ambitions: in the interview linked to above, Fund revealed that the company has plans to monetize ORL through the sale of data services. For $1,200 a year libraries can get information on the usage of members of their institutions on the ORL site. In effect, the business model turns the traditional library on its head: rather than gathering data on the use of its collections (which drives acquisitions), a library will now have data on the activity of its users for a database that the library does not have in its local collection.

It is an open question how big the market is for data analytics of academic resources, but ORL is moving in a promising direction. If it can indeed aggregate enough OA books — if it can become the largest aggregation of all — the data it generates will indeed be superior to other data services for OA books, as scale is everything in text- and data-mining. In this sense KU is indeed positioning itself as an overlay service for all OA books, monetizing the overlay without having had to invest in every book in the collection. It is perhaps not surprising that some other OA publishers are unhappy about this.

The seismic rumble you hear is the OA community expressing displeasure that someone — specifically, KU — decided to take that community at its word. OA is all about reuse — so let’s reuse all the OA books. A CC BY license permits commercial exploitation — so let’s exploit the OA books commercially. The disgruntled OA publishers now sound a bit like the grumpy traditional publishers that have complained all along that making things open has consequences, however unintended (or sometimes intended), that have to be anticipated and taken into account when developing policies and practices. Perhaps “open” should not be an unqualified term; perhaps there are shades of open and those nuances can and should be captured in different kinds of licenses. For example, if OA book publishers do not like the prospect of KU (or someone else) aggregating the books they publish, why not simply use a CC BY-NC-ND license? This form of license would enable unfettered reading and sharing of the work, but would put some restrictions on reuse. Such licenses do not mean that derivative and commercial reuses can’t occur — they simply require asking permission first (essentially, having the discussion that many OA publishers complain KU did not have with them).

What is clear is that simply wishing that the world work a certain way does not make it work that way. Practices must evolve; over time they change a bit, then a bit more. The global obsession with thinking about publishing as a comprehensive system that can be designed from the top down keeps running afoul of the vagaries of the way people actually think and work. For all the idealized platforms and manifestoes, we really live in a world captured by cartoonist Roz Chast, the world she calls “Unscientific Americans.”

Discussion

18 Thoughts on "Internal Contradictions with Open Access Books"

As a librarian concerned with patrons being able to find content relevant to them, I think the ORL is long overdue. As a librarian at a very small institution, I am dismayed that their pricing structure is “one size fits all” and not tiered to institution size like almost all electronic content licenses in our industry are. It’s not reasonable to charge the University of Prince Edward Island (4,200 FTE) the same price as the University of Toronto (90,000 FTE). But back on the main point, the nice thing about OA CC-BY licenses is that if anyone doesn’t like ORL, they are free to develop their own competitor. Springer-Nature (for instance) could have done it, and still can. And with their much greater IT infrastructure and customer base, they could probably drive KU totally out of business pretty fast. And maybe they will, and maybe Elsevier and even the University of California will create their own competing platforms too, and we’ll see some nice old-fashioned free market competition in a sector (publishing) that is really not used to “free market economics” playing any kind of role in their business models.

I think the misstep was claiming the publishers as “partners” … using CC-BY content originally published by another entity doesn’t equal partner.

“we’ll see some nice old-fashioned free market competition in a sector (publishing) that is not really used to ‘free market economies’ playing any kind of role in their business models”? Melissa: can you say more about that? Academic publishing is in fact dominated by large commercial-conglomerate publishers (such as Elsevier, SpringerNature, etc.) that have thrived precisely because of the ways in which they have taken advantage of “free market” economies, and in the spirit, also, of free market capitalism, they have dominated that market (accumulation). Perhaps this is what you mean: that because certain companies have dominated the market, “free market” competition has diminished and we need more “players” competing? Because, again, given the dominance of certain for-profit players in this landscape, the likelihood of a truly open, diversely multi-player “marketplace” for academic publishing is a bit of a foregone conclusion already. Curious to hear your further thoughts. Also, it’s important to know that the ORL is not really “long overdue,” when you already have both the OAPEN Library (which currently houses over 10,000 titles) and the Directory of Open Access Books (DOAB), which serves as a discovery service (with direct, unimpeded access to actual content) for close to 17,000 titles, and counting. So the ORL is not offering anything “new,” actually, as it is claiming it is doing (even its value-added “exclusive” services are already available from organizations such as OAPEN and DOAB, and for FREE, I might add).

One thing KU might consider is simply toning down the rhetoric around the supposed uniqueness of what they are building: it is not unique, it is not new, and it is already at its inception much less comprehensive than these other repositories / discovery services (Muse OPEN is another similar service that will also, one hopes, prove highly valuable to librarians and readers who want to access open books content and to have it available via platforms that follow the best practices for the curation, discovery, dissemination, and preservation of open ebooks and their associated metadata). I for one have no problem with there being multiple repositories for OA books: I am more concerned about the rhetoric KU is using to tout its supposedly “new” service as the *only* (and supposedly, best) place one would supposedly go to access OA books content.

Related to that, part of my own objection to the Open Research Library is, again, precisely to their own claims re: the ORL’s comprehensiveness, which is anti-competitive in the extreme. If you look closely at KU’s own press statements re: the ORL, their claim is that it will be the *one* place where *all* OA books content can be accessed, the *one* marketplace with *one* “salesforce.” I myself want to see a more rowdily diverse ecosystem for OA books that can operate at multiple scales, which is why I am especially enthused (at present) about the Invest in Open Infrastructure project, recently launched by SPARC and OPERAS, among others (and this has already received wide support from within the OA community): https://investinopen.org/. In their joint statement, the IOI shares that, “It is clear that the needs of today’s diverse scholarly communities are not being met by the existing largely uncoordinated scholarly infrastructure, which is dominated by vendor products that take ownership of the scholarly process and data. We intend to create a new open infrastructure system that will enable us to work in a more integrated, collaborative and strategic way. It will support global connections and consistency where it is appropriate, and local and contextual requirements where that is needed.”

Do we really want, or even need, just “one marketplace” for *all* OA books, or should we be looking instead to participate in the collective, community-led development of heterogeneous but also networked and distributed infrastructures for OA books that would allow the integration and interoperability of a multiplicity of OA books initiatives at various scales, yet would also “scale small” where that is desired and beneficial, such as in certain highly localized contexts? In other words, do we value diversity that incorporates and thrives with different scales of alliance and interoperability in the OA books landscape, or do we want a centralized, monopolised OA monoculture? KU is claiming the latter is what researchers and librarians want, and I myself hope that is not the case. At the very least, if researchers and librarians do want this “one-stop hub” for all OA books content, do they want it to be managed by a for-profit company only (keeping in mind that the ORL also runs on software provided by the for-profit company Biblioboards who have made it clear in conversations relative to the ORL — thanks to a webinar hosted by KU on May 21st — that they have no real knowledge whatsoever of the OA scholarly communications landscape, so they have a steep learning curve to climb)? Let’s just say…I hope not. Also, Knowledge Unlatched is actually a small-ish company with a little over 2 million dollars in annual operating revenue (as of 2018: kudos to them for being transparent, as a for-profit, regarding their financials): can they actually handle all of the initiatives they have feverishly & aggressively launched in the past year (KU Open Funding, KU Partners, KU Analytics, KU Journal Flipping, KU Marc Records, and the ORL, etc.)? From what I have seen of the ORL and its functionality, my provisional answer at present is…no. The ORL is simply duplicating other efforts that have been underway for years now (again: DOAB, OAPEN, Muse OPEN, etc.) and which have been steered and managed by trusted partners within the OA community. When asked repeatedly during their own webinar on May 21st why they were attempting to duplicate (or even, cannibalize) the already existing repositories for OA books (such as OAPEN, with whom KU is already partnered, and in fact, KU supports OAPEN with fees each year, and good for them for doing so, I might add), Sven Fund was at somewhat of a loss for words: he repeatedly stated that he did not want to say anything about other repositories since they were not present during the webinar, although he shared a few thoughts regarding what might be their flaws: ingest too slow, content (the books? the metadata?) not “granular” enough, and “technology” not as advanced, or as sophisticated, as what Biblioboards has to offer (no further details were provided). Fund also indicated he would continue to be partnered with OAPEN and to support them as well. Perhaps it is just me, but there’s more to the story here than anyone is being “transparent” about.

There is very little about scholarly publishing that fits into the ideals of free market economics. Governments overwhelmingly pay the biggest costs of production of the central product, then grant monopoly copyright power to mostly-private/commercial interests. There is also no substitutability of goods. The consumers who have the demand (eg faculty) do not directly pay for them or control the budget that pays for them (the library). I’m not very familiar with the other platforms you mention – do they all offer high quality marc records, IP-range based usage data, and openurl-compliant item-level linking? To your long and loaded question about whether we want uncentralized distribution or centralized, my answer is “both” and my point is that we can have both. Those willing to pay for the extra services (in the spirit of “software as a service (saas)” in the open source sphere) will be happy to have that centralized option, while those who prioritize those other advantages you list can make other choices. The existence of ORL in no way precludes or undermines the development of any of those. If they offer a needed service, they’ll stay in business and if not, they won’t. That’s the ideal of free market economics, and so rarely seen anywhere in North American economies in such a pure form. If you don’t like it, don’t buy it, but don’t presume to judge what other people’s/institutions’ needs and priorities are or should be.

Wasn’t there a controversy almost identical to this a few years ago? Someone was bundling articles from open access journals and selling them to make a profit. People were upset about it but it’s explicitly allowed by the CC BY license agreement. They really should have chosen a non-commercial license if they didn’t want people making money off their papers.

That would have been the Apple Academic Press dustup from 2013:

http://rrresearch.fieldofscience.com/2013/08/how-many-for-profit-publishers-are.html

More recently was the scandal over Flickr looking to profit from CC BY licensed photographs:

https://www.plagiarismtoday.com/2014/12/02/the-flickrcreative-commons-photo-flap/

As noted by the author here, if you don’t want folks to commercially exploit the material, then don’t insist on a CC BY license, where allowing that exploitation is a deliberate intent. To wit, Eileen Joy’s comment above — if you really don’t want a particular outcome, then choose instead a license that allows you to steer the marketplace away from it, rather than granting everyone the freedom to do everything and hoping that folks will only do what you want them to do.

OA book publishers already make their money even before the book is online or just afterward. There is nothing more to earn from the distribution chain afterwards. Why would they then invest legal ( in confronting ORL) or financial resources (in developing a competing aggregator) when clearly there is no 1 cent to be gained. Hence the mild responses.

The bigger issue is those who use the OA books to produce print versions and sell on Amazon at a very high price than the publishers themselves.

I randomly checked some titles at the ORL homepage, and I found several books with more restrictive licenses than CC BY.

Some random examples:

CC BY-NC: https://openresearchlibrary.org/content/ff8bf72d-7c62-447f-bdee-ca7e3d95bf4b

CC BY-NC-ND: https://openresearchlibrary.org/content/7eb1acfe-c87e-4eab-8d6b-e939a6a826b7

So seemingly the fact that these books have more restrictive licenses did not save them from aggregation. But of course it is absolutely possible that KU has asked for permission in order to use these books in the collection.

These may not be restrictive enough to achieve what some may want?

Was reminded of this recent conversation about how NC licenses are difficult, if not impossible to enforce: https://twitter.com/ReaderMeter/status/1134201336688340992

I’m afraid that everyone, including Joe, isn’t quite getting what my, and punctum’s, real objections are to KU’s Open Research Library. It’s *not* about the licenses, which is what I had hoped I (via punctum’s Twitter account) had made clear, but it’s worth restating here: the issue for us, relative to the ORL, is really *not* about the licensing, so please do not assume that somehow we are naive about the reuse of OA content: we are not. Just FYI: all punctum titles *do* carry the NC (Noncommercial) designation, partly because in the Humanities and Social Sciences (more so than in the Sciences), researcher-authors, and especially also artists (we publish quite a few artbooks and exhibition catalogs), are actually very concerned that their work not be reused within contexts that would enable bad-faith, or even twisted / inaccurate, appropriations of their thought and research, and because we also publish quite a few authors who do not have secure institutional positions, this is simply one way for them to have a bit more control over their own intellectual property. The NC (and also ND/No Derivatives) designation (if authors choose this) merely allows for what might be called a “brake” in the downstream movement of any work that allows authors, and publishers, a bit more control over reuse, while still allowing open access to reading and sharing. We allow authors to choose whichever CC (or other copyleft) license they prefer, and if there is a funder involved with any of our publication who requires, for example, the most minimal CC-BY license, then we happily comply with that, as at the end of the day, we are a researcher/author-centered press. The fact remains that the majority of our catalog carries the NC designation (our standard license, when authors indicate they are happy to leave the decision to us, is BY-NC-SA). In the May 21st webinar that KU hosted to address concerns over the ORL, Sven Fund indicated that, regardless of the CC licenses attached to specific titles in the ORL, KU would not be attempting to monetize that content, but rather, are asking libraries to support the technical infrastructure underlying the ORL, with a “[f]uture development roadmap to be decided upon by a high profile board of publishers and librarians.” He also stated that it was important for KU to keep “infrastructure” and “content” split from each other, vis-a-vis what they are asking libraries to fund, which is a striking comment, given that KU is also asking libraries to fund the opening of both OA books and journals content via other of their initiatives, which indicates that, while KU wishes to draw a clean line between “infrastructure” and “content” in the ORL, in terms of its funding, they are already working, for profit, on both sides of the supposed divide. The fact remains that KU is still positioning the value of this technical infrastructure as a centralized gateway to a comprehensive repository of OA books content, and therefore, a for-profit company asking libraries for funding to support the current and future development of the ORL is, in fact, a commercialization of that content, without which, there would be no library at all. At the very least, KU should think more deeply about the potential legal challenges they could face from publishers whose works carry the NC or ND designations and whose participation in the ORL has not been collaboratively coordinated in advance.

Having said all of that, however, again, the licenses are not really the issue for me, for punctum, or for other individuals and groups (such as Open Book Publishers: http://blogs.openbookpublishers.com/open-book-publishers-statement-on-knowledge-unlatched-and-the-open-research-library/) who have expressed dismay or resistance to the ORL. We all understand that CC-BY and other CC licenses (especially if they don’t carry the NC and/or the ND designations) allow the reuse of OA book content, which can be scraped, downloaded (etc.), and moved to any number of sites where it can be reshared, kitted out with various “extras,” and even monetized. I personally don’t spend one minute of any day worrying about this, any more than I worry about 3rd-party sellers on Amazon.com offering to sell punctum’s paperbound editions at twice what we offer them for on the same platform. I mainly worry about the readers who actually pay for these things when all of our titles are easily downloadable, for free, and without login credentials of any kind, at our website, at OAPEN Library, at DOAB, etc. So, no, the complaints about KU’s ORL are not a bunch of OA publishers and OA organizations getting upset because they somehow are so naive that they don’t understand that OA content is licensed for open reuse, including monetized reuse, and therefore this post really misrepresents the reasons why some of us are upset about the ORL. Because yes, Joe, some of us *have* thought about how adopting different CC licenses would require others to seek our permission for certain types of reuse, thank you very much, and in the case of punctum books, at least, we embrace the NC designation for precisely the reasons you outline.

The objections (of some of us within the OA books community) has more to do with what Open Book Publishers say in their own statement about the ORL:

“ORL is of course completely free to use our content: our books are openly available to everyone. However, we object to KU’s attempt to position its privately-owned platform as a ‘one-stop hub’ to access open content in an attempt to monopolise access for commercial gain. As OPERAS have said in a statement criticising the ORL, ‘the approach of this platform closely resembles well-known internet strategies to quickly achieve a dominant position by aggregating all available content and offering a free service to the community, while aiming for a lock-in of users and stakeholders.’ In the process, ORL replicates services that are already openly available elsewhere, provides only a limited version of open content that is more fully available on other platforms, and attempts to cannibalise the revenue streams of the Open Access (OA) publishers whose books they feature – all under the guise of providing a service to libraries and to the OA community as a whole.”

This may be a weird way of putting it, but our primary concern has to do with how KU “brands” and “positions” itself: what it *says* its values / strategic goals are as a company, and what it actually does, if that makes sense — especially at a time when different companies and groups are striving to both enclose and also open up vital infrastructures for scholarly communications. The troubling issue here, then, is how, historically, KU has positioned itself as a member of a community devoted to collective and collaborative forms of and infrastructures for Open Knowledge. Supposedly neither on the publisher’s side nor the library’s (as Fund has indicated in multiple interviews), KU presents itself as a a “neutral” and “agnostic” broker between the two, and yet, at this moment, KU appears to be emerging as a competitor in what it views as an OA “marketplace.” KU has also referred to the ORL as “neutral” and “agnostic.” This feels somehow “all of a piece” with how KU has also misrepresented its transition from a Community Interest Corporation (registered in the UK) under the leadership of Frances Pinter, to a for-profit (GmbH) company (registered in Germany) under Sven Fund’s managing directorship. In a news update issued in March 2016, KU presented this transition as an “expansion” into a “new branch,” when in fact Fund, under the auspices of his for-profit, “strategic investments” firm fullstopp, was acquiring and transferring the majority of KU’s “assets,” leaving behind a completely separate research and analysis group focused on ecosystems for OA monographs, KU Research, which operates independently of KU. According to Frances Pinter, in an interview with Richard Poynder in November 2018, she has stepped down from KU Research and Cameron Neylon, KU Research’s new executive director, and Lucy Montgomery, Head of Research for KU Research, “are in the process of developing a new business plan for KU Research, which will include a formal change of name to avoid confusion.” Further, “Fullstopp and Knowledge Unlatched GmbH have no role in KU Research” (although it is my understanding that KU GmbH has donated a portion of its profits for several years to KU Research: whether or not this will continue, I have no idea). See KU Research’s news release regarding the leadership transition at KU Research here: https://kuresearch.org/news9.htm.

So, of course, Joe and others are *correct* that KU is perfectly within its “rights” (for the most part: they’ll have to jump the ND/NC hurdle at some point, or be turned back by it) to create the ORL, but it also makes sense to question their rhetoric about its supposed necessity and value when other such “libraries” already exist and offer better value (and are not proprietary nor commercialized), especially in light of how KU positions itself as a community-led entity. No, no one got anything “in writing” relative to the “spirit” of what I refer to as an OA Community (touché: insert smile here for Joe), but there is such a community, as distributed, disparate, asymmetrical, and partly ungoverned as it may be, and it is represented in *so* many organizations and collectives that exist within the OA publishing landscape right now which see themselves as part of a “community” that values and is pursuing open-source, community-owned, non-proprietary infrastructure for open scholarship, which include SPARC (in no. America and Europe), OPERAS, HIRMEOS, OpenAIRE, the Coko Foundation, ScholarLed, the RadicalOA Collective, CLACSO-Latin American Council of Social Sciences, DARIAH, Invest in Open Infrastructure, OASPA, Public Knowledge Project, JROST (Joint Roadmap for Open Source Tools), ORFG (Open Research Funders Group), Educopia, Center for Open Science (etc.), all of whom are currently working on ways to collaborate and provide better governance for the further development and sustainability of open infrastructures for OA. It is precisely in light of this (and even in light of the recent launch of IOI: https://investinopen.org/docs/statement0.2), that KU’s announcement of the ORL came as somewhat of a surprise, primarily because KU is always posturing as a member of a “community” with which it is now in direct competition, developing services no one asked for or that others are already doing better and in non-proprietary ways.

I myself have many mixed feelings. I want to say that we can have for-profit *and* non-profit actors working well together in the OA landscape (there is room for many players, in my opinion, all operating at different scales and offering uniquely valuable products and services), but in the case of KU’s Open Research Library, there is a severe disconnect between the values KU claims it shares with the researcher & library & OA publisher communities and what appears to be a business model increasingly predicated upon platform capitalism, rent-seeking, and proprietary lock-ins. KU has built up a lot of trust and good faith with the library and publisher communities whom it has served over the past several years (since 2012, at least), and I wonder if they shouldn’t give some more thought to this before rushing into so many new initiatives. Is it their right to do all of this, as a company? Of course! But if their aim is to rush into all of these initiatives so as to hoover up all of the library budgets designated for OA content & services, with no concern for how this might affect the health of the larger OA community, it’s worrisome. Which also brings me to: no, Desieditor, OA books are not funded up front, or even shortly after publication. That situation only applies to presses who ask for BPCs (Book Processing Charges). Many OA publishers (including the presses in ScholarLed, but also platforms such as Open Library of Humanities) are against BPCs as they exacerbate inequities in the publishing landscape (and really, they’re terribly cost-inefficient, compared to APCs, which work better in the journals landscape), and depend instead on consortial library support, which is actually a highly effective and cost-efficient way to underwrite OA books and to also maximize the capacity of OA publishers. In the case of a publisher like Springer Open, who do in fact get BPCs up front, the ORL will feel like less of a threat, but it is still significant that KU announced the ORL as, again, a “collaboration” with publishers, and yet some publishers, like Springer Open and Open Book Publishers, whose titles feature prominently in the ORL’s beta release, were not consulted, which simply means: messaging disconnect, KU!

KU is highly aware (I am certain of this) that their success up to this point has partly been based on all of the good will that Frances Pinter rightly built up within the library community when KU was a Community Interest Corporation and was not seeking “profits” so much as it was seeking to “unlock” content, period, in the service of the public interest. Which is my long-winded way of saying: KU, please be more honest about your aims, and don’t overstate, or oversell, the value, or supposed uniqueness, of your initiatives. And don’t assume that a monopolistic centralization of content and data is what scholarly communications needs right now. And don’t be so greedy. Or be greedy and own up to it.

Open Book Publishers charges an annual fee of $500 per library for MARC records, different formats (mobi and epub are not free by default), and probably some statistics about their (to date) 146 published books. https://www.openbookpublishers.com/section/44/1

KU’s Open Research Library charges an annual fee of $1200 for something of a similar service, but about several thousands of books.

Is it really such a big difference?

Probably one of the most interesting aspects of OA books are the usage statistics (both for the authors and the publishers), but it is pretty difficult to obtain such statistics if the content is freely distributed on many different platforms, which often do not provide such statistics openly and for free.

Open Book Publishers do not “charge” for these “services.” That is not how library support works for all OA content / OA platforms. The money pledged to platforms such as Open Library of Humanities (journals) and OBP (books) is specifically pledged to support the production of actual content. The catalog records, stats (etc.) are perks of support / membership, not the products being “purchased.” Likewise the ORL is asking libraries to help subvent the infrastructure, not the content, and again, the value-added services are “perks” of support. It’s important to understand how consortial library funding for OA is determined & what it is for, specifically. Anyone can download MARC records from OBP’s site. Library support = we support your platform, its capacities & further development. By supporting your platform, we’re also supporting the progressive transformation of scholarly communications. What we ask in return is that you follow best practices for the citation, discovery, dissemination and preservation of your content, and oh yes, thank you for these open catalog records and usage stats, which are meaningful to us but not the “things” we are “purchasing.” The California Digital Library has an impressive review procedure and checklist for helping them determine which OA initiatives UC Libraries should support (they support OBP, btw), and nothing on the list is: stuff we get. It’s all about supporting the ongoing, high quality production of OA content, including supporting things like journal flipping (OLH).

This discussion should also consider a recent article in Against the Grain on the topic of automating library collection development (Denise Koufogiannakis at the University of Alberta libraries). KU is creating a service that allows academic libraries to automate the collection of OA content. Libraries have fewer staff resources to dedicate to even long-standing mainstream collecting methods. This has presented a major challenge in the path of the success of a fragmented, ‘ghettoized’ OA content universe. KU is finding a solution and will learn and adjust along the way. As those of us working in the distribution world know all too well, the costs of making content discoverable, and especially *accessible*, are too frequently undervalued when not entirely overlooked. I once had a professor who said, ‘I give everyone an A. That way no on complains.’ He was joking, but his point was that by critically engaging, there would be controversy. Hats off to KU for raising very worthwhile controversy.

It’s kind of weird how many people in this thread keep stating that KU is helping to provide a valuable service to libraries that supposedly does not already exist. Michael Zeoli above refers to a fragmented, “ghettoized” OA content universe. First, try not to use “ghetto” as a metaphor — it’s in poor taste, in the same way it’s in poor taste to refer to a horrible wage, or job, as slave wages, or slavery, or indentured servitude, etc. More importantly, yes, there is a lot of OA content out there that is not centralized enough in helpful ways (to library communities, to user-readers, etc.), but in the case of OA books…simply not true. Between OAPEN & DOAB alone, we have over 17,000 books all aggregated in one place and with excellent, open infrastructure. Libraries *already* have the opportunity, through their open services, along with Project Muse, JSTOR, etc. Over 110 publishers deposit their books with OAPEN. KU is playing catch-up against organizations it is supposedly partnered with and cannibalizing its content from these other services as well. But, please, everyone keep saying the Open Research Library is addressing a void in open content services. It’s not.

Libraries will vote with their support of the service. From everything we have seen to-date, support for KU is strong and growing in academic libraries. So much so, in fact, that it will undoubtedly attract the attention of the large aggregators, ProQuest and EBSCO. If they choose to engage, competition for best OA service to libraries will get stronger. OAPEN and DOAB have done great work – so. libraries may see no advantage in KU. Our words here will have no influence. I will say that loading OA content onto a platform is not sufficient in terms of providing a service – why the value of *service* has been remarkably badly understood. As for the choice of the word ‘ghetto’, yes, maybe best to leave words like that alone, but to go again to Italian, ‘Chi vuole intendere, intenda.’