Editor’s Note: If scholarly publishers truly consider themselves service providers, then collectively a better job can be done in making the journal submissions easier for authors. Custom templates, arcane requirements, and obtuse author instructions waste the time of scholars and make resubmissions difficult. Today’s post is by Mriganka Awati, Academic Research Specialist for Editage, Cactus Communications. She studies data and trends related to scholarly publishing and writes reports, articles, or white papers based on the results of her analyses. In the past, she has worked as a scientific editor, trainer, and author educator, and is the lead author of two Editage books focusing on academic writing for non–English-speaking researchers.

The global scholarly publishing industry includes over 33,000 peer-reviewed English-language journals, a number that continues to grow steadily. Despite this enormous figure, the main stages in the publication cycle, the overall roles journals play, and the requirements for original research papers are fairly similar across journals – more so within broad disciplines. Yet, journal systems, processes, and guidelines can vary substantially even within the same discipline. For an established industry of this scale, scholarly publishing conspicuously lacks standardization in these areas.

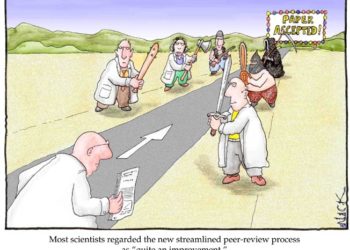

Authors often receive advice on how to get their papers published, including the dictum that they should strictly follow journal guidelines on how to prepare and submit manuscripts. Many journals return or reject incompletely formatted manuscripts or incomplete submissions. Authors risk coming across as unprofessional or careless, because if they cannot take care of a relatively simple task such as following guidelines, perhaps their academic work may suffer from the same neglect.

No author wants either of these two outcomes, and most sincerely try to follow journal guidelines, and so the lack of uniform and simple journal systems and guidelines creates an additional burden for authors.

Author Perspectives and Why They Matter

From a broad perspective, problems related to journal systems and requirements may seem almost inconsequential beside other issues in academic publishing. However, the findings of a large-scale global author survey conducted by Editage indicate otherwise. In this survey, one of the questions authors were asked was, “Is there something you would like to change about the academic publishing system?”

We analyzed the responses received and found that complexity in journal systems, processes, and guidelines was among the top problems respondents wanted addressed, behind publication delay, poor peer review quality and processes, and high publishing-related costs (in that order).

Of the 2,515 comments analyzed, 233 (9%) mentioned this problem. A closer look at these 233 comments revealed four related perspectives. Specific comments are included below verbatim (or with minor grammatical revisions for clarity), though some were translated, as the survey was available in multiple languages.

Perspective 1: Journal guidelines should be simple and clear

Several authors discussed having to deal with conflicting, hidden, incomplete, or unclear guidelines, and some said that journals should share templates so that it is easier for authors to adhere to journal requirements.

“Submission guidelines of journals are sometimes ambiguous and I am lost how to interpret them.”

“Journals should provide a checklist that fully discloses and organizes all formatting requirements in a logical order. Journals should not hide additional formatting requirements inside the submission window or sections thereof.”

“Often the guidelines provided for authors on the journals’ websites are confusing and sometimes contradictory. This is especially true in the case of the instructions provided for preparing and submitting the electronic artwork and the table of contents.”

These views are consistent with other findings as well. In response to another question from the same survey, 66% respondents said that they found journal guidelines unclear, incomplete, or both. A different survey of East Asian authors had shown similar views on journal guidelines.

Further, a study of the author guidelines of 80 international English-language journals indicated that many do not clearly provide the information that authors need. Journals tended to score better on the completeness and clarity of formatting instructions than on instructions for submission/post-submission processes and ethical requirements.

Another interesting finding from the survey of East Asian authors mentioned above was that a major gap exists in perceived clarity and completeness of international journal guidelines between East Asian authors and international journal editors, with twice as many editors as authors believing that they are clear and complete. Further, 53% authors from the same study said that they followed journal guidelines carefully, whereas only 12% of journal editors believed that authors did so.

Such large gaps in perspectives are far from ideal and can cause journals to be frustrated with authors and vice versa. One strong and clear takeaway from all these studies is that journal guidelines need to be thoroughly and regularly reviewed and improved from the perspective of authors who are required to follow them, especially non–English-speaking authors.

Perspective 2: Formatting requirements should be standardized/harmonized

The most common view across all comments was the need to have standard guidelines across journals because of the difficulty in adapting manuscripts to different formatting requirements when they are prepared for submission to a new journal.

“One thing that would make writing/submitting easier is standardization in manuscript styles. Too many journals have their own ‘custom’ style. It’s getting ridiculous. Sticking to a handful of accepted styles; MLA, APA, Vancouver, etc. (maybe an international style) should be sufficient. And journals must do a better job providing clear style information in their guidelines. Researchers and writers shouldn’t have to worry about nit-picky style concerns and standardization should make editing/publishing much easier and efficient.”

“A universal format for all journals. This will smooth the process of making subsequent submissions after rejection.”

“In many journals, different rules are applied: in formatting of reference list and usage of words. It requires a lot of work for submission for each journal. These rules on writing a manuscript need to be integrated in one rule.”

“For non-English native, checking manuscript guidelines of each journal and revising work of manuscripts are hard work. Therefore I hope the guidelines to be integrated to some extent. Especially a requirement for abstracts and word/figure limits of text differs from journals, so I have ever chosen the journal with a similar guideline for a next target journal for easy work, when my paper was desk rejected before.”

The formatting-related frustration experienced by authors has not remained unnoticed by publishers. Efforts have been made to alleviate the problem. Some journals have clarified that format does not affect their editorial decision as long as a manuscript has all the required components (for example, see this). Some publishers have adopted policies that do not require authors to follow any specific manuscript format at the time of submission (e.g., Elsevier’s Your Paper Your Way and Taylor & Francis’ Format-Free Submission).

As welcome as such initiatives have been, they have not yet been put into practice on an industry-wide scale. Therefore, this still leaves authors struggling with complex or divergent requirements – most of which have no bearing on the research content.

Potential reasons for the vast diversity in journal requirements include interdisciplinary differences, differences in journal size, staff strength and resources available, journal objectives, target readership, and stylistic preferences. While many of these are understandable reasons for inter-journal differences, together, they can result in guidelines so disparate as to cost authors significant effort when adapting a rejected manuscript to a new journal.

This problem has been voiced before, with a call for standardized or harmonized journal guidelines to solve it (e.g., here and here). The author perspectives presented in this post strongly emphasize the need to navigate a way around all inter-journal differences and establish universal standards, at least within broad disciplines.

Perspective 3: Submission systems need to be universal

A challenge shared by many authors was the need to create and manage multiple accounts for multiple journal submissions (sometimes for the same manuscript), and the common suggestion for addressing this was to have a universal system (or at least similar systems) to submit manuscripts and track their status across journals.

“The difference of publication systems for each journal is a disadvantage for authors and reviewers. It should be integrated as possible.”

“Even if it is a same submission system, an account has to be made for each individual journal. Integration would be an improvement, including automatic entering of information like Author name, Affiliation, Contact details etc.”

“Try to make the process of publishing similar in all systems to make them author friendly.”

Articles by some individual authors have already highlighted the need for universal journal systems (e.g., here and here). Journals and publishers, as well as authors, strongly desire efficient journal workflow systems, and efforts are being made to improve them. However, doing so has proven to be complex, with one of the major reasons being the lack of standardization among journal processes and requirements. Therefore, the previous problem seems to be, at least partly, getting in the way of practical solutions to this one.

Admittedly, it is no easy task to standardize journal systems/guidelines while duly considering unavoidable journal-specific needs. Perhaps, then, what is needed to surmount these problems is to shift focus and examine the technical details and differences against a bigger picture. This brings us to the next perspective.

Perspective 4: Too much time is wasted in journal submission and formatting

The most strongly expressed sentiment with respect to journal systems and guidelines was that they require authors to spend excessive time. Many authors viewed time spent on formatting as unproductive and adding little value to their work. Some felt that journals should not demand total compliance with formatting instructions at the time of submission, when the fate of a manuscript is not clear.

A few authors were even of the view that they should not have to perform manuscript formatting since it does not affect manuscript content and is primarily the concern of publishers.

“Journal formatting requirements are absurdly complicated and non-standardized. Moreover, few journals have consistent and clear explanations of their requirements available. Complying with unnecessary formatting guidelines is a huge time sink for editors and authors, while conveying no benefits to science.”

“It is meaningless to ask authors to format manuscripts before it is even clear whether the manuscript will be sent out for review. It is a waste of authors’ time. I have seen one journal that has eliminated this requirement and states that all formatting is allowed before acceptance, which I find to be extremely helpful.”

“Submission guideline is too detailed. Formatting reference lists and adjusting tables & figures to guidelines are not essential for papers and those are publishers’ work.”

At 9%, the proportion of survey respondents who commented on the overall theme of complexity in journal guidelines, processes, and systems may seem rather small. What makes this theme noteworthy is that this problem is very closely connected with the time it takes authors to have a manuscript published. As mentioned earlier, publication delay was found to be the top concern authors wanted the academic publishing industry to address (36% of the analyzed comments had mentioned this theme).

When we think of journal-specific factors determining the time taken to publish a manuscript, we typically think of the time from submission to decision and from acceptance to publication. This, however, is an incomplete picture because it does not account for the pre-submission time taken by authors to adhere to a journal’s requirements or use its submission system.

This pre-submission time may not seem substantial at the level of an individual researcher, but may be cause for worry when viewed from a wider perspective. Around 3 million articles are published each year. Even if we consider a conservative estimate of 4 hours as the average time needed to format a single manuscript for a particular journal and to submit it via the journal’s manuscript-processing system, this amounts to half a million days (~1,370 years) of global researcher time spent every year on just manuscript formatting and submission.

The actual figure is likely to be far higher since most manuscripts are not accepted by the first journal they are submitted to, and some may not get published at all even after being subsequently submitted to other journals. Indeed, it would be interesting to examine how much time authors actually spend trying to follow journal guidelines on manuscript preparation and submission.

Procedures for submission and manuscript preparation are undoubtedly critical in academic publishing. If, however, they are a massive drain on global researcher time, it is important to scrutinize them, prioritize what is critical for authors to take care of, and address the rest in a manner that shifts the burden away from them.

Approaches to Achieving Uniform Systems and Guidelines

Standardizing journal systems and guidelines will require everyone in the scholarly publishing industry – researchers, journal editors, publishers, societies, research organizations, etc. – to universally acknowledge the problem, show collective willingness and initiative to address the problem, and collaborate effectively to do so.

A possible way to achieve all this is to institute a global task force or committee on manuscript preparation/submission standards. This group could comprise experienced journal editors, publishers, and active researchers (including peer reviewers) from multiple disciplines and geographies, whose objective will be to define essential criteria for the quality of journal guidelines and submission systems.

This group could offer audits of journal systems/guidelines and provide a score or some form of accreditation. It should also define the minimum essential criteria that all author submissions should meet before they are processed by journals (with respect to manuscript format, references, completeness of information, etc.). These criteria may vary for each broad discipline. Journals should be strongly discouraged from requiring anything more than these criteria from their authors at the time of submission.

The advantage of having a global body will be that it can help overcome non-important inter-journal differences that might otherwise persist. However, the industry need not wait for such a body to address author concerns. Until universal agreement is reached on any of these issues, journals could take the initiative themselves to address this problem, as some have already done.

I propose a simple checklist that journals can use to evaluate their guidelines and systems and decide how to improve them from an author’s perspective.

- Importance: Which guidelines are absolutely important for authors to follow at the time of submission? Those that are not can be omitted and taken care of after manuscripts are accepted. Which requirements of the submission system are critical to the workflow?

- Clarity and consistency: Are the guidelines worded carefully so as to be understood easily by researchers for whom the journal will be of interest, especially non–English-speaking researchers? Are any guidelines potentially ambiguous or conflicting?

- Completeness: Have all the guidelines been provided in a logical fashion in one place? Are any manuscript-specific instructions missing on the website but provided only when the author uses the submission system?

- Adoption of existing standards: Instead of enforcing unique styles and preferences (e.g., for references, nomenclature/terminology), can the journal simply adopt common and already existing standards that best suit its needs?

- Time: How much time would it take a first-time author to prepare a manuscript per the journal guidelines or navigate the submission system? For authors’ benefit, journals might consider providing an estimate of this time on their author guidelines page.

- Tools/templates: If a journal has many requirements for manuscript preparation, including unique styles, and it cannot limit them, can it provide the author a template that can save a significant amount of time/effort for both the author and the journal? Can it build tools or direct authors to existing technology that can help in manuscript preparation?

- Author feedback: Have authors shared their feedback on any of the above aspects? Journals can administer short, occasional surveys to proactively seek feedback on the clarity/completeness of guidelines, the ease of following guidelines/using submission systems, and the time taken for manuscript preparation/submission. Author inputs can help identify the most common pain points that need to be addressed.

Discussion

8 Thoughts on "Guest Post — A Case for Universal and Simplified Journal Systems"

This is a very useful article and a reminder that the devil is often in the (sometimes mundane) details when it comes to publishing.

I worked with a client years ago that was the leading publisher in their discipline. We were redesigning their submission and review process and we brought in some of their key authors and editors. The first thing they told us was to remember that authors submit to many places and we shouldn’t design something that would diverge too much from what other people were doing. It’s such an obvious point but still important.

Or, authors might do well to target a journal where they have a reasonable chance of getting published, rather than starting at the top of the impact factor ladder and step by step (rejection by rejection) coming down to the appropriate level – with each rung of the ladder incurring formatting costs. If instead they submit to the right level, the number of rungs (hours of formatting costs) will be considerably reduced.

Second, “that is publishers’ work”, sure. However delivering content in a shape that requires more and more work for the publisher while at the same time requesting lower and lower cost of publication is a hypocritical attitude. If authors want lower publication costs, they better make the work of the publishers less by abiding by the formatting rules that have been set precisely to keep costs low (because the processing is geared to that type of input).

That does not negate the fact that unifying the format that publishers’ processing systems are able to “eat” is not a bad idea; all would benefit (except for the enabling of impact factor hunting, see above). The reasons put forward here provide, however, as much blame to the authors (if not more) as to the publishers.

The entire premise of this proposal is that it is actually possible to get everyone to agree to a single “ideal” situation for submission, peer-review, and publication.

Given the number of authors who clearly are not even communicating with each other about the papers on which they themselves are all listed as authors, I find the concept intriguing but unlikely to ever bear fruit.

As for the dreaded “formatting requirements”: If you can spend three days typing LaTex code into a paper to pull reference and figure citations from other documents, you have all the time you need to make the paper single-column and double spaced. What else is any publisher actually asking for?

I spent several years early in my career doing peer review administration as my full-time job, processing >1600 new submissions/year (average >6.5/day) not counting revisions. I’m sure some things have changed in the mean time (e.g., ORCID integration into submission systems), but here are some thoughts from the trenches:

First, I do want to say that I’m sympathetic to authors’ struggles (particular due to my own struggles when I applied to grad school and when I submit job applications), and I always tried to act with empathy when dealing with authors. It was always in my mind that even though I worked in our peer review system eight hours every day and everything seemed intuitive to me, this might be the first time any particular author had ever interacted with the system and they shouldn’t be expected to be a power user.

However, the sheer amount of inattention to detail and/or attempts at rule bending that I encountered from authors was staggering. We had simple, clear submission instructions but something close to a quarter of all submissions came in with huge problems (e.g., being twice as long as our length limit) and needed to be returned to the author prior to review. We only screened for a few things prior to review (e.g., length, valid email addresses for all authors, but not citation style or page layout formatting). I also answered a large amount of email from authors who had not yet submitted asking questions whose answers were clearly spelled out in the submission instructions. Even clear, short, simple author instructions were straight-up ignored; it doesn’t matter how simple or clear they are if the authors never actually read them! No matter what, a significant fraction of authors will simply never read the instructions.

I think if the author of this post wants to delve further into this topic, she needs to look into why journals have the rules they have, talking with not only academic editors but also the staff members who do the hard day-to-day work of running a peer review system. To paraphrase G. K. Chesterton, you should know for what purpose a gate was erected before you propose tearing it down.

Working for an academic publisher, I agree with these points and am also surprised at how many authors ignore basic guidelines and checklists before submitting. I would love to see universities and research institutes offer a basic course/workshop on publishing that covers the nuts and bolts of preparing a manuscript for publication (e.g., format, references/citations, copyright law).

Thank you all for your comments. The objective of this post was not to apportion blame or to negate the pain points experienced by people on the editorial/publisher side of the scholarly publishing system. It was to bring to the fore views shared by a large global sample of one segment (authors) on this subject, which other stakeholders in academic publishing may not have access to. Naturally, the issues outlined in the post may not apply to all journals or may apply to varying degrees. Nevertheless, I believe that getting a glimpse of author perspectives may help journal stakeholders take a step back and evaluate whether they can make small improvements to their author-facing communication and processes.

Also, while this post voices the challenges faced by authors, it definitely does not absolve them of their share of responsibility in ensuring smooth publication. No doubt there may be instances where author habits/practices are problematic, but again, this may not apply to all authors and such instances may occur in varying degrees.

As an organization that provides services to help authors at different publication stages, Editage (the company that performed this survey) also offers educational support for authors on responsible practices that can make things easier for editors, peer reviewers, and publishers. For example, we know that authors struggle to select the right journal and try to submit to the highest possible impact factor journal (and the strain that this puts on journals), so we try to educate authors on how to choose the right journal and why they should not focus only on the impact factor. We also try to expose them to publisher and editor perspectives, and to this end, we publish interviews with journal professionals, where they share experience-based tips for authors on how to navigate the publication process, the importance of reading the journal aims and scope, etc. From the interest and engagement we see from authors, we know that many are sincerely interested in understanding what journals expect from them and how to meet those requirements.

In this context, I’d like to reiterate the perception gap between authors and journals that I mentioned in this post, particularly that between non–English-speaking authors and international journal editors. There is substantial diversity among journals with respect to how clear or extensive their guidelines are, how author-friendly their systems are, and how often these are updated. Some journals and publishers undertake considerable efforts to make their systems author-friendly. But we have also had some publishers tell us that they had never revisited their author guidelines since the journals were instituted, or updated their systems to keep pace with changes in submission trends (e.g., increasing geographic diversity of submitting authors).

All of these factors emphasize the need for a global task force or committee on submission standards. We need a single body that has an understanding of the perspectives of all stakeholders, can examine all pain points/perspective gaps further, and propose measures to minimize submission-related problems. Individual surveys or studies can only go so far in these efforts. The objective would not be to reach an ideal situation of complete agreement but to bring some harmony within a system that has frictions between segments because there are no minimum standards at all.

I had a managing editor that said trying to get a group of authors to do something the same way was like trying to herd cats. It appears authors have the same view of publishers.

This is a timely article. I do believe though that authors should be free to format their article in any reasonable way they wish, and submit in any reasonable format (Word, PDF, LaTeX, XML). The technology is out there to automate the bulk of the required conversion, formatting and metadata extraction – with manual checks, which would always be needed in any case, even if authors use provided templates.