Opening the inaugural NISO Plus conference in Baltimore last week, NISO Director (and Scholarly Kitchen Chef) Todd Carpenter reminded attendees that we had come together to solve problems and set standards for the information that surrounds scholarly and professional publishing programs — and that this enterprise was an inherently social one, despite the myriad data-driven, inter-linked, lightning-speed, high-tech advancements at hand.

This struck me as a profound way to frame the gathering and set a democratic tone to our endeavor, a reminder that we are each responsible for both the challenges we face and their remedies. In an era where neural networks and cloud computing have made artificial intelligence part of daily life, it is important to remember that these are made possible by our own invention.

Despite the decades-old — instead, humans are at the helm and we are in control of our destiny. We design and control the computational loops wherein we accelerate our processing of information, products, and services — therefore, we cannot be at the mercy of these creations, in fact, we are the loop. From Siri to autonomous vehicles, the magic of tech innovations are wrought by our own ingenuity. Therefore, setting boundaries around these technologies is also an utterly human activity, with inherently cultural implications.

The social dynamics of information standards were clearly on display in every session I attended regarding content discovery and access, where stakeholder handshakes are critical junctions in the research lifecycle. Regardless of what type of access controls are in place, at its most basic, much of scholarship today is made possible by a successful handoff of authorization between research institutions and resource providers. Given the recent launch of SeamlessAccess.org, and its first collaborative implementation in GetFTR, progress toward a more fluid SAML-enabled authentication was a hot topic of discussion in Baltimore.

The RA21 promise of a frictionless researcher experience requires specific social conditions to be fully realized. Publishers and other platform providers must configure support for federated single sign-on (SSO) access using SAML technologies. Institutions must then also join a federation, develop identity management capabilities, and configure each publisher site or database to which their researchers are entitled (often in the hundreds). While this type of SSO access is enjoyed now among the biggest publishers and top research institutions in the most wealthy countries, a universal solution is still a ways off.

There are approximately 5,400 members participating in some sort of SAML-based access, which means some readers will be left out of this equation, as the REFEDS map demonstrates. Alongside our conversations about how to streamline SAML setups for libraries and institute optional levels of privacy to suit a range of institutional policies, it was clear in these sessions that building on an identity-based infrastructure will require more effort toward collaborative partnerships than computational protocols.

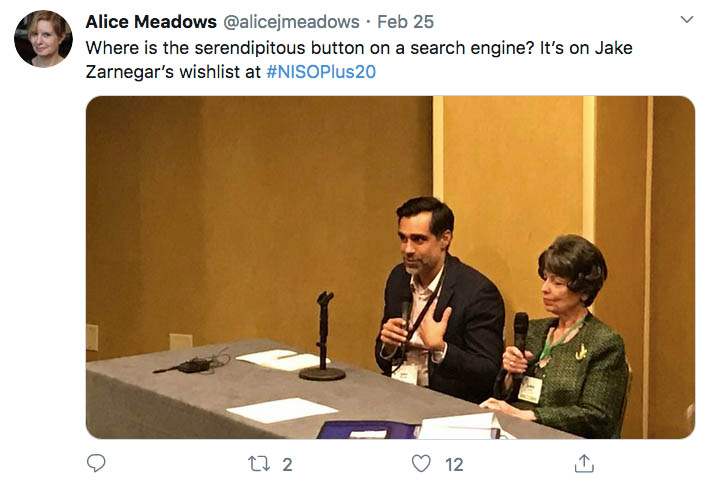

Just scanning the Tweets from #NISOPlus20, you can see the messy social realities of our tech-driven scholarly ecosystem oozing across the posts.

Whether I joined a group moving chairs into a circle to brainstorm the next extension of the KBART guidelines, or the content-rich pre-conference on artificial intelligence, the biggest hurdles were in balancing the practical and the ethical, the possible with the acceptable. The sharpest tool in our kit was not Python coding, but the fine art of creative compromise. In fact, these are the magic elements of an effective product manager — a critical function to successful publishing programs, which was more expertly addressed in this conference than any other I’ve attended in this industry. We sit at the intersection of technology and research, which requires bringing social solutions to bear every day.

Maybe you’re scratching your head by now and wondering if this concept is just too obvious to spend any time on — humans create tech, therefore tech is a human enterprise. So? What does that imply? As humanity evolves in ever more algorithmic ways, I believe it is critical to be reminded of our role and responsibility in what comes next. Being aware of the social solutions to mechanical problems allows us to be clear about the methods and instruments available to us — those devices I’ve heard dismissed too often as “soft skills” — communication, compassion, and cooperation. And I think it’s an important reminder of our biases and situated realities, and that cultural progress requires rising above these subjective versions of truth to accept the multiplicity of our information experiences.

The closing keynote by danah boyd brought this theme full circle, illuminating the societal impacts of our algorithmically informed digital experiences. Based on her research into data and society, boyd reminded us that we have immediate responsibilities to think critically about the technology we implement, to consider unintended consequences, to be willing to slow down and ask the hard questions. We must be aware not just of what data we make available to the world, but also what data is missing; these are often the ‘data voids’ that skew search toward racist results. She challenged NISO attendees to consider what publishers and libraries can do to close the vulnerabilities left behind by social search trends and other automated mechanisms we have come to accept into everyday life.

As we closed the final session, an attendee asked Dr. boyd what techniques she suggests to champion a greater understanding of algorithmic risks to society. Her answer reminded me of a maxim I’ve heard from every champion of social change that ever lived, as she explained that the only thing that ever works to change minds is connecting with people in calm, considerate conversation — much as we saw for 3 days at NISO Plus 2020. The world we live in is made possible by each of us individually stepping up and assuming responsibility to do our part, to come together to shape the society we live in — perhaps a timely reminder for those of us looking ahead to the Super Tuesday primaries in the United States!

Many thanks to Dr. Bohyun Kim, CTO & Associate Professor at the University of Rhode Island Libraries, for the lesson on how humans function in / on / off the loop with artificial intelligence, https://www.slideshare.net/bohyunkim/the-potential-and-challenges-of-todays-ai.

Discussion

7 Thoughts on "Humans are the Loop: Social Solutions to Technological Challenges"

Out of curiosity. Does Dr. Boyd (?boyd) truly wish to spell her name in lower-case (a la k.d. laing or e.e. cummings)? I say because it appears in lower-case twice.

Yes, the lowercase spelling is correct (as in bell hooks, to add to your list).

Yes, that’s right — see more here, https://www.danah.org/name.html — thanks for your careful read!

From her Wikipedia entry:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Danah_boyd

Once she reached college, she chose to take her maternal grandfather’s name, Boyd, as her own last name. She decided to spell her name in lowercase so as “to reflect my mother’s original balancing and to satisfy my own political irritation at the importance of capitalization.”

I very much enjoyed this article and it was a great way to start my Monday. The reminder that human connection (ostensibly, it seems at times) still remains at the heart of all of this work is well taken. A tension is raised here between setting boundaries around technology and information access as an ultimate expression of our humanity and the changing of minds through interpersonal connections. I would take this one step further and say we’re coming to terms with our settling for what we know how to do (or believe we will learn how to do) and realizing it’s really a question of pursuing what matters most to us.

Peter Block in his book Stewardship writes “There is depth in the question ‘How do I do this?’ that is worth exploring. The question is a defense against the action. It is a leap past the question of purpose, past the question of intentions, and past the drama of responsibility. The question ‘How?’–more than any other question–looks for the answer outside of us. It is an indirect expression of our doubts.”

The conclusion above nails it with the ideas of danah boyd. The social dimension is about making meaningful connections while creating room for the expression of those doubts, which allows dissent back into the room. That’s how we move beyond the need to change minds and to truly connect.

Yes, “an important reminder of our biases and situated realities.” Both researchers and those who publish their work, may benefit or suffer from the results of that research. Researchers and publishers may become situated by the realities of a child with leukemia, a sister or mother with breast cancer, or a father with prostate cancer. Given such common challenges , there are personal and institutional biases. For a researcher it may be doing the most fundable experiments rather than those that they believe will best advance knowledge. For those in the publishing industry it may be satisfaction with all completed enquiries of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) not being freely available online (with appropriate redactions when necessary). I could go on … .

Thanks so much for this great writeup of NISO Plus, Lettie! As I think you know I 100% agree re the importance of the social vs the technical. I’d also like to note that, in a similar vein, Amy Brand (The MIT Press) rightly pointed out in her opening keynote that just making content open is not enough. The risks there may be a bit different (consolidation among the big players, lack of a level playing field, sustainability of open infrastructure, etc) but the overall challenge is the same – that technology alone won’t solve our challenges.

(Full disclosure – I’m Director of Community Engagement at NISO)