In February, the Chinese government released two documents that set forth important changes in policies governing science research evaluation. One of the most eye-catching changes is the requirement for researchers to publish one third of their representative papers in domestic Chinese journals, which is being hailed as a big boost for Chinese publishers. Will all the 5000 STM titles published in China benefit from these new policies? How do Chinese publishers themselves interpret the documents? In this post, three Chinese publishers explained how they view the new policies. Yuehong (Helen) Zhang is the former Director of Journals, Zhejiang University Press, and former Editor-in-Chief of Journals of Zhejiang University-Science. She was a Council member of ALPSP between 2010-2016, and a board member of Crossref between 2015-2017. Daliang Zhao is the former Director of Xi’an Jiaotong University Journal Publishing Center, and Deputy Editor in Chief of the Journal of Xi’an Jiaotong University. Dr Xiaofeng Wang is the Chief Editor of Chinese Laser Press (CLP), and serves as an editorial board member of Learned Publishing and Acta Editologica.

Helen Zhang

I have shared these views in an article published in The Intellectual (an influential WeChat channel), and am happy to share them again with The Scholarly Kitchen.

If we are supposed to treat the newly released documents as the new guidelines of scientific research evaluation, I have three questions:

- Shouldn’t the documents be sent to the scientific research teams in universities and institutions for extensive discussion, or a survey been carried out first through questionnaires before their release?

- The documents say: “the domestic STM journals with international influence are determined by referring to the catalogue of journals selected by the Action Plan for the Excellence of Chinese STM Journals (abbreviated as the Excellence Program)”. Personally I don’t think this is appropriate. Isn’t this the “domestic SCl” catalogue, and does it imply that journals outside the catalogue do not have, and will not have international influence in the next 5 years?

- As the main stakeholder of academic journals, can researchers’ contribution as editors to academic journals be taken into consideration in the evaluation system, as stated in the Hong Kong Principles released at the 6th World Conference on Research Integrity, “recognizing essential other tasks like peer review and mentoring”?

In summary, the academic evaluation system should encourage researchers and research institutions to use high-quality, credible, open, and verifiable data sources to promote scientific innovation.

Daliang Zhao

Two major measures are announced in the documents: first, papers are not used as the basis of evaluation except in basic research; second, only representative works are required, with specific limits on the number of papers published (five for an individual, and 10 or 40 for teams).

While this may be good news for researchers, it is bad news for journals! My rough estimate is that there will be a 50% reduction in submissions. With such a dramatic reduction, what will happen to journals? Some might think that only foreign “SCI” (Science Citation Index) journals will be affected, and domestic journals will be fine, but this is far from clear.

According to the documents, a “representative works” system will be used for evaluation of papers, and no less than one third of the representative papers should be published in domestic Chinese journals. High quality papers should be published or presented in three types of journals or conferences (called the “three types of high-quality papers”). The list of domestic journals meeting the requirements of “three types of high-quality papers” will reflect those included in the earlier policy guidelines offered by the Excellence Program.

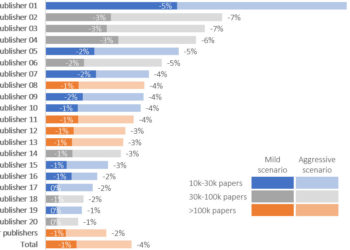

So only one third of the representative works will remain in China. Still, it seems to be better than before when almost all good papers were published outside of China. However, the first choice of domestic journals will be those in the Excellence Program. How many titles are there? At present, there are less than 300, which will increase every year, and the majority of them are English titles. With the decrease in total number of papers, no requirement on publishing for applied science, and backflow of papers concentrating on a few hundred top domestic journals, what can the average journals publish?

Furthermore, according to the documents, publishing expenses for representative works and “three types of high-quality papers” can be paid for through the special fund of the National Science and Technology Plan. Expenses for other papers cannot be paid out of this national fund.

This would prevent any projects of the Ministry of Science and Technology from being published in journals that are not the “three types of high quality”. If a researcher does publish in these titles, then they will have to pay out of their own pocket. The publishing costs cannot be reimbursed from the project budget. National projects do not need you, ordinary journals!

Finally, papers are not required for applied science research for evaluation. Where will a large number of journals on applied science, including clinical medicine titles, get papers from in the future? Isn’t this an over-adjustment of policy?

In my opinion, this important document has given further clear guidance for science research evaluation, but there is still a lot to be improved upon and built by all stakeholders.

Xiaofeng Wang

There are foreseeable benefits to Chinese STM publishers:

- Following several other policies released in recent years, the documents consistently highlight Chinese STM journals. For example, they require one third of representative papers be published in domestic journals, although this does not guarantee that all domestic journals get high-quality manuscripts. Publishers still need to focus on improving journal quality, producing top domestic journals, and then competing internationally.

- The documents mention that papers are not used as primary indicators for technical development and research projects. Some people may think that this will reduce submissions, which is not good for journals. But the policy does not forbid researchers from publishing papers. I think that not forcing researchers to publish papers, especially in SCI journals, actually gives them more publishing options. For example, they can now publish in Chinese, which would benefit domestic dissemination and communication. In addition, mandating all professionals to write papers also leads to misconduct in publishing, as we saw from time to time.

- The documents encourage publishing high-quality papers in high-level journals, and recommend journals included in the Excellence Program. Moreover, it allows publishing costs to be paid out of the research fund. These are all good news for the journals in the Excellence Program, and will greatly facilitate the development of those titles.

- Establishing the blacklists and early warning lists will provide protection for the growth of good domestic journals. Under the pressure to publish more SCI papers, Chinese researchers spend tremendous energy on publishing. While the strict limitation on issuing new Chinese journal licenses has ensured high standards for launching new titles in China, many overseas predatory publishers continuously lower the standards to attract Chinese submissions. The system of a blacklist and early warning list will reduce the phenomenon of “bad money driving out good money”.

On the other hand, problems may arise that deserve attention.

The Document sets a limit on the number of representative works, which helps with reducing the weight of paper quantity and moving to improvement of paper quality. But combined with the requirement of “three types of high-quality papers”, will the high-quality papers all go to such journals as Nature and Science (except the one third published with Chinese journals)? These world-class journals are always the authors’ first choice. Will the emphasis on a limited number of masterpieces strengthen the dominance of the journals on top of the pyramid? If so, it will not be good news for the vast majority of Chinese STM journals under development. Of course, the appeal of top journals is always there, and so are the tiers of journals.

“Evaluating a paper by the journal (where it is published)” has always been criticized. The argument is that the quality of an article is not directly correlated to the Impact Factor ranking of the journal, and the number of citations and downloads cannot be used to evaluate the academic quality of a paper. The documents also clearly propose to discard evaluation by publication, but meanwhile it mentions that “the research results published in ‘three types of high-quality papers’ can be evaluated as high-quality achievements”. These “high-quality papers” are still published in influential journals or conferences. Is this not another kind of evaluation by publication?

When encouragement on publishing high quality papers is linked to certain journals, such “encouragement” is likely to become an unspoken requirement (to publish in certain journals). In recent years, many countries, including China, have been advocating multi-form publication and rapid dissemination of papers, of which preprints are an important form. On the contrary, the policy in reality still attaches importance to publishing in some “famous” journals.

There has been criticism that SCI is a capitalist business model that misleads the development of scientific research in China. But SCI is just a tool, and what function it plays is in the hands of those who use it. I believe things are developing for the better, but just not as fast as I would like to see.

Acknowledgement: The three Chinese publishers have respectively published their opinions in WeChat channels. The author thanks them for sharing their views with The Scholarly Kitchen readers.

Discussion

6 Thoughts on "Chinese Publishers React to New Policies on Research Evaluation"

Hi Tao,

Thanks for continuing your coverage of this – it seems like the ripple effects of this document will be felt globally. The shift towards assessing quality over quantity is very welcome, but do you know whether it will be accompanied by steps to eradicate the system of paying authors for every article they publish? That system seems to another big driver of submissions from Chinese researchers.

From this recent post:

https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2020/03/03/guest-post-how-chinas-new-policy-may-change-researchers-publishing-behavior/

“According to these documents, the Journal Impact Factor (JIF) and Science Citation Index (SCI) should not be used as the most important criteria when recruiting and promoting personnel. Universities and research institutes are not allowed to provide monetary incentives for publishing in SCI-indexed journals.”

Hi Tim,

As a researcher works in China, I can share my personal experience with you. It depends on:1) what journals do you publish with, 2) what fund do you have.

If a paper got published in top journals, it will be paid by university/institute/ fund, or the author will be refund / reward if not payed directly/immediately though the third party. Most public fund in STM field cover APC in China, but for HSS studies, it is difficult to get fund to cover publishing cost. China’s National Social Science Fund stopped to pay for APC and language polishing fee since 2017 I think. I spent 8000CNY in 2019 to publish two research papers in two CSSCI (China Social Science Citation Index) journals. That was totally new to me, because I used to pay for publishing with the fund that is one, and two, these journals used to don’t charge for publishing. I remember that I used to get honorarium for publishing with some Chinese journals a few years ago, small money but called royalty.

I personally welcome the new policy, because I can take my time to focus on my interested research topic and write good quality papers or even monographs, no pressure on publishing more “salami”papers, but the pressure of publishing in top journals is getting much more bigger.

What will I do under the new policy? I think I will still submit my best works to best journals. There are good journals both in Chinese and English language in my field, so I got lucky and freedom to choose journals. For my “inferior” works, I will submit to the “secondary” journals, if they charge APC, I will probably give up. Because it adds no value to my CV. It sounds very pragmatism, but that is what most researchers do. That is why I said in my guest post “predatory journals will loss it’s market in China”.

It is very interesting to see the views of the three Chinese contributors to this topic. I think, however, in assessing the likely reactions to the policy we need to consider the wider context. There are three aspects that have come up in recent posts on this: (1) the move to using five representative works in assessments for grants and promotions; (2) the requirement for one third of the paper output to flow to Chinese journals; (3) the deprecation of the use of WoS SCI indicators in assessments. Looking at each in turn:

(1) Quality over Quantity. The adoption of the five works policy is not actually completely new in China, a representative works policy has been in place at NSFC since at least 2016. It has also been in place in many areas of the world outside China. There is no evidence that a move to representative papers in assessment schemes anywhere in the world has resulted in overall declines in paper output. The reasons for this are complex but basically derive from the fact that when authors choose five representative papers they do so from their personal output. The main driver of personal output is that to be a researcher you must conduct and publish research. Researchers publish to establish priority, communicate to peers, and get esteem for their work. Evaluation systems sit on top of this; they may amplify or affect direction but do not seem to have any effect on the fundamentals (see Mabe: Does journal publishing have a future? in Campbell et al. (eds) Academic and Profession Publishing Chandos, Oxford and Mabe and Mulligan (2011) What journal authors want New Review of Information Networking 16.71-89). Consequently we should not expect such a policy alone to have a reduction on Chinese paper output, especially when investment in R&D in China is growing at 17% CAGR.

(2) Requirement for one third of paper to be in Chinese journals. This requirement is unlikely to divert top papers from the international journals as these remain the key ways in which researchers achieve the esteem and impact they need.The main effect will be in China on Chinese titles, and there are a limited number of these that publish in English and have overall broadly lower reputations than the international ones. Only 285 titles are listed in the Chinese Sci-Tech Journals Excellence Plan (see http://news.sciencenet.cn/htmlnews/2019/11/433140.shtm ) half of which are Chinese language titles. It is unclear that there is enough capacity to handle the papers that would be diverted by the policy. Clearly the range of titles would need to expand (and the recent policy does foresee investment in improving Chinese domestic journal publishing to do this, although it is unclear how easy or quick this might be). This will actually provide new opportunities for international publisher-Chinese publisher journal copublication start-ups.

(3) Deprecation of SCI indicators as a basis for assessment. This is happening generally all over the scholarly world, but while the Ministry documents in China deplore “SCI supremacy” as a basis for assessment for promotions and grants, they also make clear that these indicators do have a use in identifying quality titles.

My overall conclusion is that, yes, domestic Chinese publishers may find things tough if they cannot evolve and adapt to these policies, but I am less convinced that this will result in an overall reduction of papers. If research labs remain closed for a very extended period due to CoVid 19 pandemic restrictions this is more likely to have an effect in the medium term than any other factor.

China has a highly centralized government and research is largely funded by public. A policy made by the central government may have a much stronger influence compared to many other countries. The provincial governments have been releasing new policies recently, and those are pretty much copies of MoST document. The real effect also depends on how the policies are implemented. NSFC has changed their application process for fund and the online form does not allow a 6th paper be listed. This is a new rule applied for the first time this year. Moreover, some researchers I know (these are senior in their professions) welcome the policy and feel relieved from the pressure to publish. From these signs, I think that a move from quantity to quality will happen, but I agree that the drop of number will mostly be seen on lower quality journals. Top journals may even see an increase of submissions because of the emphasis on publishing in Three High-quality publications.

Are there any predator Chinese journal lists?