Last week The Scholarly Kitchen shifted focus from our regular bloggers and guests to research and researchers writing about structural racism. We highlighted race and medicine, Library and Information science, physics, policing in Australia, and the history of American racism and activism. This week we have shifted the focus back to Scholarly Communications, asking what it offers for understanding structural racism, including within our own industry. Today we want to draw attention to two posts from 2018, published anonymously at the request of the authors and contributors — all people of color — whose testimonies make powerful and shameful reading for a sector that likes to think of itself as liberal and inclusive. These important stories demonstrate the change needed — at the individual and institutional levels — to make scholarly publishing the welcoming and inclusive community it could and should be.

On Being Excluded: Testimonies by People of Color in Scholarly Publishing Part 1

This blog post is co-edited by two people of color who work in scholarly publishing. Together, we have nearly 15 years of experience in this industry. As the idea for the blog post came together, we knew that sharing our stories needed to be done anonymously.

Yet we are eager to have our stories heard. Most micro-aggressions we experience pass without comment. We remain silent. And so do our allies. It is hard to speak up when you are alone in a white-dominated space. We hope that other people of color in our industry read this post and understand that they are not alone. We also hope that our allies will understand that they must do more if they want to claim that label.

The stories below came to us from across a range of departments and presses. We collected more stories than could fit into one blog post, so we will be submitting additional blog posts to the Scholarly Kitchen. Several new contributors have already agreed to share stories and we welcome additional contributions. Please contact our host, Alice Meadows, for more information on how to connect with us.

Testimonies

Years ago, during my then press’s annual Thanksgiving celebration, one entirely white department came in to great fanfare dressed as “Native-Americans” for “fun.” Obviously, I can’t speak to how all of my other colleagues felt, though some were clearly amused and delighted by it, but I do remember that I and the one other person of color on staff immediately made eye contact with each other with a look of total dismay.

I was the only person of color in my department. When I asked the administration why they didn’t do outreach to more students of color or promote people of color, the answer from the HR rep was, “We can never find any black students who are qualified or are able to pass our proofreading tests. You were our first and we were really surprised when you passed. Usually people like you don’t make it past the first round. And since there are so few to begin with, there aren’t any to promote.”

I left six months later.

During my second year as an editorial assistant I asked our Editorial Director if I could attend the AAUP (now AUP) annual meeting. I suggested that I could apply for two grants to help cover the costs of attendance, the newcomer grant and the diversity grant. At that time, I was the only person of color in my department and another assistant also wanted to attend the conference. Our Editorial Director asked me to limit my applications to the the diversity grant so that my white colleague would have a better chance at the newcomer grant. He proceeded to explain that there were almost no minorities who attended the AAUP so I was practically guaranteed to receive the diversity grant. Angry and hurt that I was being reduced to my brown skin, I went back to my office. A few days later, I explained to him that I would prefer to apply to both since I qualified for both grants. I received the newcomer grant that year, and a different person of color received the diversity grant; I was glad to have been there to meet her.

As the only black person in my department, my supervisor once told me: “I just want to let you know that I like you. You’re not like the others…in the Mailroom, and IT, and Security. You don’t blast your music, talk loud, and leave early. I see you reading books and bringing your own lunch…I just think that’s really good…Keep it up. You might even get to move up a bit.”

I feel real anxiety when there is another man of the same ethnic background in the same room as me because there’s a decent chance that someone will mix us up, usually by calling one of us by the other’s name…I have had to deal with the same type of lazy mistake for my whole life. The incessant noise (even at low volumes) of discrimination and lazy assumptions is something that adds up over time to remind me of my otherness.

Over the course of the time that I have been at the Press, I have heard all sorts of offensive “jokes” made at staff meetings: from making light of the devastating hurricane in Puerto Rico, to joking about how a book on the DREAM Act needs to come out fast otherwise “everyone will be deported by then,” to the outright and casual usage of a racial slur. Because of the frequency of these jokes, the fact that they are consistently made by upper management (which is all white), and because I am one of few people of color in the room when these jokes are made, I am extremely tense and uncomfortable during weekly meetings with my white colleagues. Every time I walk into a meeting with my colleagues, the pit of my stomach hollows from anxiety; I’m in a constant state of defense, ready for something to be said that is offensive. I’m ready to swallow my own anger and stay silent in the name of “professionalism,” ready to be disappointed by my white colleagues and managers who regularly disregard this type of behavior as “harmless” or don’t even notice it as problematic in the first place.

I was on a business trip with my boss and it was the first time that the two of us had spent significant time together away from the office. During the last night of the trip, we talked about personal stuff over dinner. I was sharing stories about my family when she suddenly said with a laugh, “I wasn’t sure what you were when you came for the interview. You don’t look like any of the African Americans from where I come from.”

I’ve heard ignorant comments like this before but this was said by a relatively young woman who always made it known that she was a liberal feminist. I don’t remember exactly how I responded. I think I said something along the lines of, “like white people, black people come in all forms and shades,” and left it at that. I had no desire to dive into an in-depth conversation about race. It would have been a waste of time.

Working at a university press as an Asian American woman of color has been an experience of whiplash — pulled in one direction where my opinion has been valued to “authenticate” a project by or about Asian Americans, while simultaneously pulled in the other direction, having my opinion discounted and written off by my white colleagues. “Well, you’re not really Asian.”

I’ve been asked how to pronounce names of authors who are of Asian descent — but then told that they disbelieve my pronunciation is authentic. “What good are you?”

I’ve been asked my opinion on how to bring diversity into our staff — but then told that the lightness of my skin tone is a strike against me. “You don’t really count.”

I’ve been asked to communicate difficult conversations about race with authors of color — “they’ll take it better coming from you” — but then told I should call myself an ‘Americanized’ version of my name when dealing with authors who are white. “You should make it less difficult for them.”

I have been tokenized when it is convenient. I have been dismissed when my opinion might make waves. I have been split in two and torn apart inside by this industry — one that supposedly values the intellectual input — and output — of scholars who write about race, justice, and inclusion.

I was the only Black employee in the books editorial department, and one of very few people of color. This would not have been so striking had the majority of books we published not been about Black and Brown culture and perspective. Walking into this position, I understood the violent legacy of white people controlling the means of production, and thirsting to curate and cosign intellectual and creative work by people of color. This was not my first rodeo in terms of working within a majority white office with a “liberal agenda;” i.e., working alongside white people who were sure they were “good.” What offered me more hope for this office was the depth of much of the work by Black authors they published. It was work that I had read in my undergrad years and beyond, that truly shaped my theories of self and the possibilities I saw for my own Black Life. I thought to myself, there’s no way that even the white people reading, editing, and probing these works aren’t grasping the brilliance, and at the very least, the humanity of the people who produce this work. How could you spend months, and sometimes years, with a manuscript about history or theory regarding Black life, and not be in some way changed by it? But alas….

I witnessed the head acquisition editor be repeatedly disrespectful to the women in editorial who did most of the grunt work. I was often tokenized, and called on to affirm a white editor’s opinion of a Black manuscript. My supervisor condescendingly micromanaged all of my activity every single day, while simultaneously trying to appear “down,” by asking me my opinions about various facets of Black popular culture, often using black vernacular. Knowing that my colleagues saw only my blackness — and not my complete humanity — led me to be more detached at work. I didn’t mind that people didn’t know how to talk to me because I didn’t want to talk to them.

Editors took many non-black interns under their wing, and they were given numerous opportunities to rise up in the press. Black interns, on the other hand, were heavily micromanaged and there was little interest in bonding with them or making them feel at home. I saw several white interns elevated to permanent positions. This is something I never saw offered as a possibility to Black interns. I did my best to provide some sense of belonging to the Black interns when I could; but honestly, how could I provide a feeling of belonging if it was something I never felt there myself?

Hands down the most painful, bizarre situation I’ve faced as a POC in scholarly publishing occurred when I was pitted against another POC, in a similar role, by leadership. Despite our divergent interests and skills, unhelpful comparisons – overt and covert – were made. Eventually, in spite of my best efforts, and my expressed desires to work more collaboratively, I felt forced out and had to leave. Afterwards, a supervisor got in touch to ask how the house might improve its diversity efforts, and to casually ask if I had contact information for potential authors of color.

I consistently find a self-serving equation of “diversity” (an outcome) with “antiracism” (a practice) in our industry. Generally speaking, the appearance of progress and harmony stands in for difficult, never-ending work, and ultimately, the relinquishment of privileges.

Instead of diversity™, scholarly publishing needs decolonization – a complete, utter rethinking and remapping of power relationships. This means white people in the profession — including well-intentioned liberal whites, self-identified woke whites and well-meaning white allies — have a great deal of humbling and challenging work to do. Are you up to it?

Stay tuned for our next installment of testimonies of people of color in publishing. In the meantime, please feel free to take a look at the following resources available for white colleagues who may be interested in learning more about what you can do:

Additional Reading:

https://korbettmosesly.com/library

https://reflections.yale.edu/article/future-race/becoming-trustworthy-white-allies

http://www.alliesforchange.org/documents/how-racism-damages-white-people-102010.pdf

Organizations that guide individuals and institutions in anti-racism work:

https://www.alliesforchange.org/programs

https://www.racialequityinstitute.org/our-process/

On Being Excluded: Testimonies by People of Color in Scholarly Publishing, Part II

We would like to thank everyone who bravely shared their stories for both of our blog posts, as well as in the comments. We know from personal experience that the process of remembering and re-telling these incidents takes a great deal of emotional work and energy.

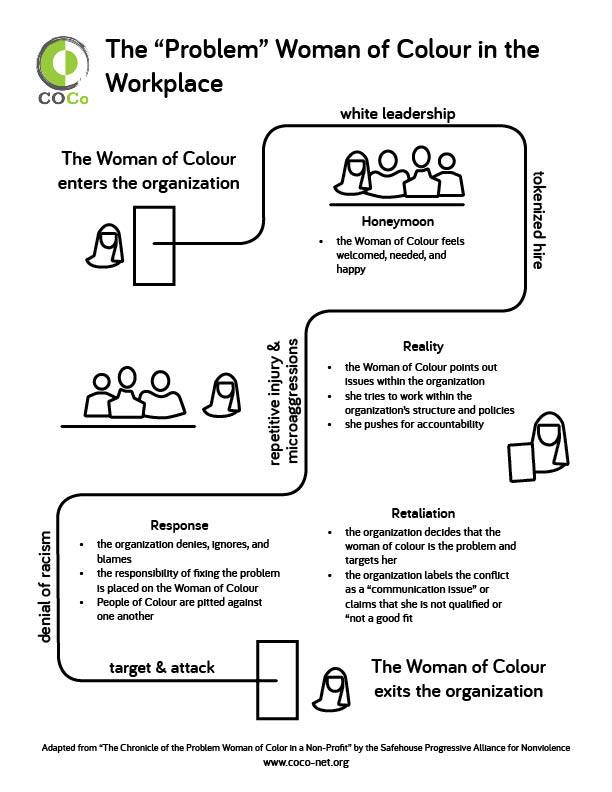

Due to space limitations we originally published only half of the stories that were submitted to us, though we included at least one from each contributor. Many contributors shared numerous experiences with us, signaling that these micro-aggressions do not happen in isolation: over time, these experiences perpetuate a pattern of exclusion and emotional violence. They add up to make people of color feel unwelcome and unsafe in their work environments, ultimately leading to significant health and professional consequences.

The issues that people of color face in our industry are not only individual, but systemic. Extensive individual and institutional work is needed if we are ever to see change.

Testimonies

I interviewed for an entry-level position in publishing with a white woman who came into the café where we were meeting, looked around several times before she realized I was waiting for her, and said to me as she sat down, “Oh, sorry — I thought from your name on your resumé that you would look different. More ethnic.”

I had always been the first or the only black professional in all my publishing jobs, so I was excited to learn that there would be two of us at my new university press. Unfortunately this presented a new problem: both of us were referred to by the other’s name on more than one occasion by more than one colleague.

During a diversity training at the press, we were asked when we first realized what our racial identity was. A middle-aged white woman at the Press turned to me and laughed, “well, you probably came out of the womb knowing!” Her exclamation made clear to me how white people assume they are the default, and that they are the only people “without” a racialized identity. Of course, I did not come out of the womb knowing that I was brown, and instead learned that I was brown sometime in elementary school through comments (like this one) and treatment that made me feel othered.

I changed my hairstyle to the texture that naturally grows out of my scalp. Afterward, I received new reminders about wearing “dressy” or “very professional” attire for certain events. Since nothing changed about how I dressed for our events, I feel this was a way of expressing a preference without having a conversation or risking sanctions.

As the only black staff member at the Press, I started to notice that I was asked to attend meetings every time there was an issue with a black author or black bookseller. At the same time, I was often excluded from higher-level meetings that were more appropriate to my role.

My boss once called me a “workhorse” and then, when I showed offense to being called an animal (because of the long and gruesome history of white people equating black people to animals), he told me that I was being “too sensitive.”

In response to increasing discussions about diversity happening at the Press I was working at, I once engaged the Editorial Director as to why he did not show any interest in being involved in these discussions. He told me he was “beyond diversity” because in his words, “diversity doesn’t solve anything.” Had he ever attended a diversity event at the Press, or bothered to listen to the women of color who led these initiatives at the press, he would have known that a critique of “diversity” and “multiculturalism” was built into the discussions that we were trying to start. But he never showed interest in any of the events, nor has he advocated for any changes at his Press that would give more power to people of color. His behavior is emblematic of the white liberal who can spot racism and white supremacy only when it exists outside of themselves, or, more importantly, only when it does not present a challenge to the power they wield in their day-to-day lives.

During my very first day as a temp at a UK-based publisher, I came to the office with a temporary ID card given to me by my manager at the interview. As I walked through the door I was shouted at by the security guard who said something to the effect of, “Look, I’ve told you multiples times before. You shouldn’t use this pass.” I was trying to tell him this was literally my first day, when he took the pass from me and marched me to reception. There, the receptionist also dressed me down for not using the right card and how I should know this by now. Neither seemed to believe this was my very first day. I waited by reception while colleagues walked past. Finally, my red-faced manager came to collect me and re-issued me the very same temp ID card. As the weeks went by I was followed around the building by different security personnel and asked to produce my card while white colleagues I was with were not. This introduction to publishing gave me the sharp realization that this company was not at all used to having a ‘Person of Color’ in their midst and, as a default, regarded me with general suspicion and contempt.

I showed a picture of my daughter as a baby to a colleague, who then said, “what a cute little monkey.” Because I am black and calling black people “monkeys” is entirely inappropriate, everyone stopped talking. She then said, exasperated, “Did I say something wrong?”

As one of the few younger women of color at my company I’ve often become associated with diversity efforts there, which has led to push back from several employees — most of them older white editors who feel that they shouldn’t be told their lists aren’t diverse enough, but some of them have been white coworkers my age. “Race is your thing, feminism is my thing,” I’ve been told by several of these white women — including some I had trusted as allies. Evidently, if you advocate for racial diversity in a field dominated by white women, you will never be anything but the angry brown minority in the room.

At conferences, sometimes other editors or authors will introduce themselves to me and then, when I say my very ordinary name, they’ll look a bit surprised and say something to the effect of, “Oh, that’s not hard to pronounce at all.” Even though this type of interaction isn’t particularly harmful or mean spirited, knowing that some people assume I’ll have a “foreign-sounding” name is startling and discouraging.

A prominent feminist author of color requested in her author questionnaire that the art on the cover of the book be by a feminist of color. This request was overlooked by the entirely white design team and the white editor whose project it was. When I brought it up to the editor, he circumvented my concerns and insisted it didn’t make a difference. I tried to push back but was ignored. The cover art for that book still features the art of a white woman, which I find especially ironic because it is a book by a famous feminist of color who regularly writes about how women of color’s voices are silenced, dismissed, and marginalized.

I’ve worked at the same university press for nearly a decade. Certain patterns are visible to me now – patterns that give shape to institutional racism. More than half of the people hired at our press have had a previous connection to someone at the press. Our press is mostly white, and the people hired with connections are also white. One hiring manager recently mentioned to me that she wanted to pay especially close attention to diversity in her upcoming hire. She ended up hiring the white roommate of a white staff member. I happen to know that this person received guidance on their application from a different staff member. When you are within the network, guidance and support are easier to come by. Hiring managers are more comfortable sticking to their networks. They think, “I know this person and they would be ‘a good fit.’ Or “This person was recommended by a friend, so it is a safer bet.” That’s all well and good, but what about all of the people who are not in the network and who have historically not been in the network of your institution? The vast majority of university presses are affiliated with PWIs (predominately white institutions) and most presses in the US were founded under legal segregation. Isn’t it time white folks delved more deeply into the systems of exclusion that emerge from a reliance on “networks?” Change will require risk-taking and intentionality. Publishing isn’t rocket science. Give us a chance and we’ll show you that we are just as capable as the people in your networks.

During my time at the press I realized that the cognitive dissonance of white people and their relationship to race knows no bounds. They could read all they wanted. They could regurgitate Black scholarship. And they could bend over backwards for Black scholars who they deemed worthy, and who essentially paved their road to salary and clout. But being that close to Black thought in no way caused them to reflect on or remedy their day-to-day abuses of power. It didn’t change their relationship to white privilege. It didn’t grow a respect for the people of color they encountered in their daily lives.

My experience led me to believe that the legacy of releasing Black and Brown work to the world must be carried out by Black and Brown folks themselves (as it undoubtedly has been and is in different pockets of the field), if there is any chance at an ethical culture in publishing.

Unless organizations and individuals engage in enduring anti-racist work, staff members who are people of color will continue to face the same issues. Sadly, this is a conversation that has been happening in the publishing world for decades, as witnessed by pioneers like Margaret Busby, Britain’s youngest and first black woman publisher. Busby faced decades of discrimination yet continues to advocate tirelessly for diversity in publishing even after more than 30 years of seeing minimal progress and change. We must follow her lead and the lead of other people of color who are bravely sharing their stories so that we can learn the range of the problems that exist and then find a way to do better.

People of color have been dealing with racist cultures in publishing for long enough. If we are to ever see significant change, efforts will need to move beyond the short-lived conversations and limited initiatives that we have seen here and there. The stories in these blog posts clearly indicate how much work is left to do to create an inclusive, anti-racist culture within our organizations.

As before, if you would like to contact us about your experiences, please do so via Alice Meadows.

Discussion

4 Thoughts on "Revisiting — On Being Excluded: Testimonies by People of Color in Scholarly Publishing"

I think these are all US examples but this is unclear. Please remember your site is visible throughout the world and so such comments may not represent the experiences of English-speaking people in, say, New Zealand, or Hong Kong come to that. (This should not be taken as implying that only the US suffers from racial prejudice and everywhere else is perfect!)

It would be helpful if comments were localised.

“Unless organizations and individuals engage in enduring anti-racist work, staff members who are people of color will continue to face the same issues. ” THIS.

I’d encourage everyone to take a look at this article from HBR, “Toward a racially-just workplace” https://hbr.org/cover-story/2019/11/toward-a-racially-just-workplace and it’s emphasis on the shift from “diversity = better business outcomes” to “Diversity is a moral question. Our business must fundamentally reorient itself not only to diversity generally but to mitigating the consequences of 400 yrs of oppression against the black community specifically.” This starts from the C-suite and the white (usually) men in positions of power. This is YOUR chance to genuinely shake your organizations at their roots to begin the work needed to become a truly antiracist organization. (Good overview of antiracism here: https://nmaahc.si.edu/learn/talking-about-race/topics/being-antiracist)

I call all orgs in #scholcomm to publicly share their plans to make this commitment. Lack of comment or substantive commitments with accountability metrics will speak volumes and impact where many of us decide to work in future.

Apologies for typos – wrote this up before being fully caffeinated!

“…told I should call myself an ‘Americanized’ version of my name…” I really HATE this! I have not experienced this personally but have had exchange student coworkers at a previous job who were told they had to choose an “English” name to put on their name tag at work. I was so offended for them. It was even more ridiculous because some of the names could probably already be considered “English” and/or were not at all hard to pronounce. How insensitive to pressure someone into putting aside their NAME – the name by which they have always been known and which was given to them by their family!! Very sorry I did not take a stand and challenge this when I saw it.