Editor’s Note: Over the last week, we’ve had two posts looking at the potential changes to the research communication workflow that are now emerging as preprints become a more accepted part of the landscape. Tim Vines suggests that preprints may change our mindset enough to allow for multiple simultaneous (and disconnected) peer review processes to take place for manuscripts. Byron Russell, John Sack, Alison McGonagle-O’Connell, and Tony Alves gave us a view of how publishers are now adapting their traditional submission pathways to integrate preprints. Both posts highlighted some of the latest initiatives that offer (at times) editorially-driven and organized peer review efforts for preprints. All of which got me thinking back to the 2017 post revisited below. How do we define what a “preprint” is, and where is the line drawn between it and a “published” article? I’ve always thought of preprints as early versions of a manuscript before they’ve gone through a complete editorially-driven peer review process. Is that the right place to draw the line, or is the sole difference the thumbs-up decision from a journal editor to accept the manuscript? Please weigh in below in the comments — what differentiates a “preprint” from a “published paper”?

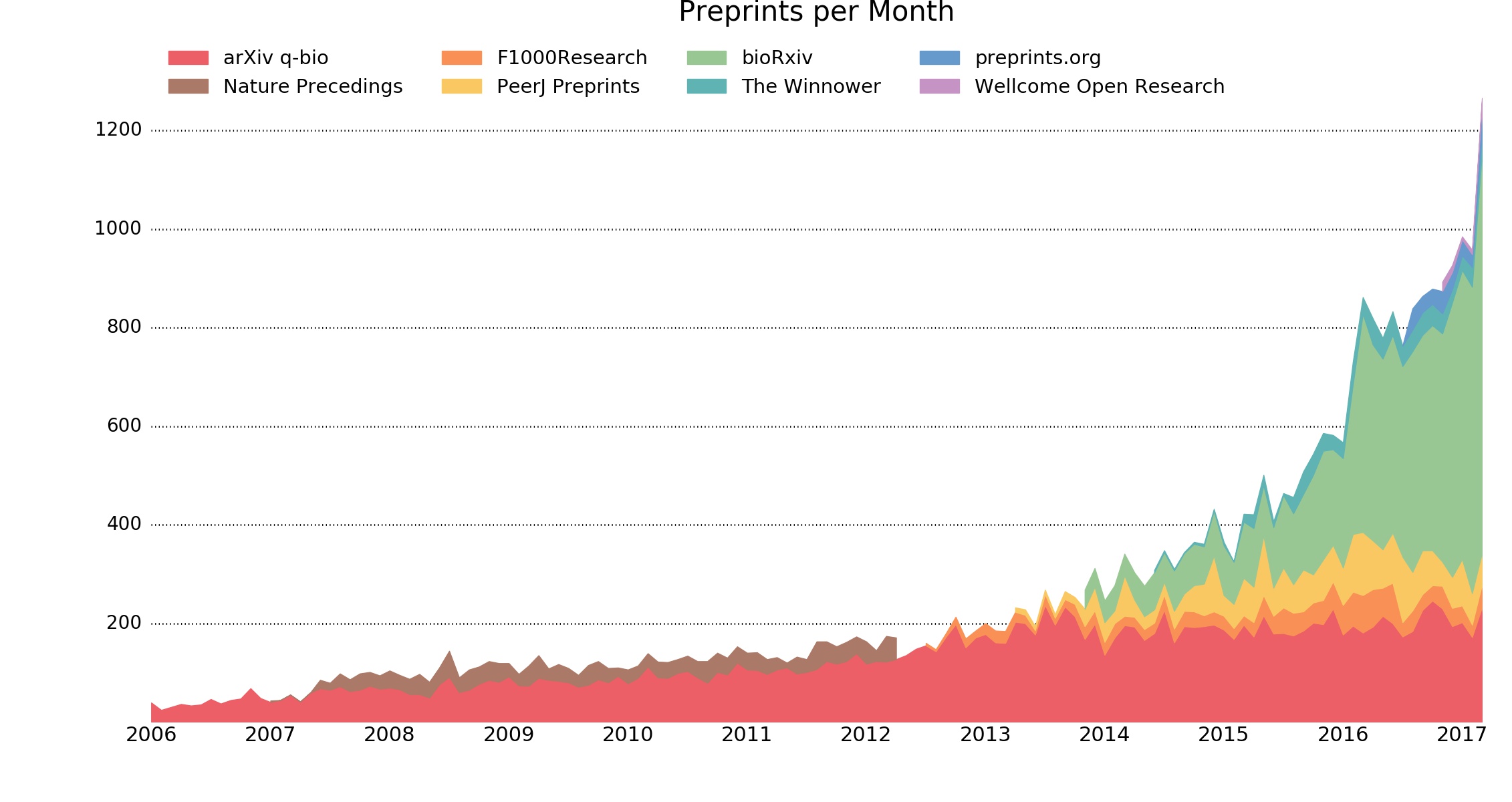

A figure in Judy Luther’s recent post on the state of preprints caught my eye (and was noticed by several commenters). The figure (below), comes from the ASAPBio site, and shows the remarkable growth of preprints in the life sciences. What was interesting to me was the inclusion of several formal journals mixed in with the usual preprint servers, notably F1000 Research, Wellcome Open Research, and The Winnower. This raises significant questions about just what, exactly, we consider a “preprint”.

ASAPBio’s definition of a “preprint” can be found here. ASAPBio seems pretty inclusive in the different types of models they consider preprint servers. Jordan Anaya, who is credited in the figure agrees, “…that F1000Research and Wellcome Open Research are not preprint servers in the sense of bioRxiv, PeerJ Preprints, and preprints.org,” but still felt they were worth including in the PrePubMed search tool. Wikipedia offers a fairly concise definition for preprints:

In academic publishing, a preprint is a version of a scholarly or scientific paper that precedes publication in a peer-reviewed scholarly or scientific journal. The preprint may persist, often as a non-typeset version available free, after a paper is published in a journal.

The key to the definition of “preprint” is in the prefix “pre”. A preprint is the author’s original manuscript, before it has been formally published in a journal. One of the primary purposes of preprints is that they allow authors to collect feedback on their work and improve it before submitting it for formal peer review and publication.

The three journals mentioned above (and presumably the new Gates Foundation flavor of F1000 Research) all work on a post-publication peer review model. The author submits a manuscript, and after some editorial checking, it is officially published online in the journal. At this point, the peer review process begins. Regardless of whether the paper is accepted immediately, revised multiple times, or ultimately rejected, it is considered “published”. The author cannot withdraw the article and submit it to another journal.

This is “post”, not “pre”. Once the manuscript goes live, it is considered “published”, and peer review is “post-publication”. It’s worth noting that you will not find the words “publish” or “published” anywhere in bioRxiv’s documentation — they scrupulously use the words “post” and “posted” instead to differentiate what’s happening from formal publication in a journal.

If a journal like Cell or Nature posted a free copy of the author’s original submission alongside the published article, would they also be considered preprint servers? Speaking of Cell, what are we to make of Cell Press Sneak Peek? Essentially, authors who submit to Cell can have their manuscripts publicly posted on a special Mendeley group open to those willing to register. Does this make Mendeley (and Cell, for that matter) a preprint server? What about journals that practice open peer review? As part of this practice, each iteration of the article is often posted, along with reviewer comments and correspondence. Are these to be considered preprint servers as well?

The key to the definition of “preprint” is in the prefix “pre”.

As new ground is broken and new models arise, new terminologies and new definitions become necessary. Preprints are generally being presented to the research community as a way to get their work out quickly, while not hampering, in any way, one’s ability to publish the work in a journal that will provide maximum career benefits. Mixing in journals that formally publish the preprint version of an article and do not allow re-submission elsewhere muddies the water about just what a preprint is supposed to be.

Getting the terminology right has implications for how research is communicated and the trust it engenders. Already, this fuzzy terminology around preprints is sowing confusion. Take, for example, this article from a recent issue of The Economist. The Economist appears to be both muddling open access and preprints and suggesting that science move to using preprints in place of journals, eliding the fact that preprints are not peer reviewed.

Post-publication peer review models are interesting and valuable additions to the landscape, but they are, by definition, publication models, not pre-publication servers. If we want to drive the use of preprints by researchers, we need to be clear about what we are asking them to do.

Discussion

19 Thoughts on "Revisiting: When is a Preprint Server Not a Preprint Server?"

This is not exactly addressing the questions raised by the post, but it’s slightly relevant (I hope). A few years ago, I was involved in a big collaborative project, and it resulted in a manuscript that the lead authors had high hopes for. It got posted as a preprint, and simultaneously started a lengthy and disappointing trek through the editorial boards of prestige journals. In the end, it never got accepted at a journal that the lead authors would have been happy with, and I’ve long since given up any expectation that anything will happen to it. It languishes as a preprint. I then wondered: what if one of the authors involved in this study, knowing that it was never going to be formally published, chose to write up their own data from this study, and published it as a smaller, less-ambitious paper in a field-specific journal (or megajournal, say)? If the preprint really is “unpublished”, then this should be fine (and I’m sure that technically there would be no obstacle to doing this); but if there is even an expectation that as a matter of scientific etiquette, say, the preprint should remain as a recognisable piece of work, what then?

Jake, I appreciate the frustration of the effort to get the manuscript published in a journal “the lead authors would have been happy with”. The all too common manuscript consigned to a desk drawer after that experience really is “languishing”. But your preprint is a discoverable, freely accessible, citable contribution to science that may be assisting other investigators in all kinds of ways.

The approach you suggest – authors writing up their own data from the collaborative study – is reasonable, practical, and from the point of view of etiquette, requires IMO only that they discuss the plan with their collaborators and consider any reservations arising from the terms of the collaboration. Few journals in biomedicine now object to the submission of manuscripts that have been preprinted, in whole or in part, and many actively encourage preprints and seek them out. Your preprint has a DOI specific to the server you posted it to. When a version or derivative of that preprint is published in a journal, it will acquire a DOI specific to the journal. If the preprint and the published version are sufficiently related, Google Scholar and other discovery services will automatically recognize the association and the preprint server will make the link, if that’s SOP for the server (it is on bioRxiv and medRxiv). So the publication architecture is in place to support the approach you’re suggesting, if the authors concerned can unwind their contributions to the work from those of their collaborators.

“What differentiates a ‘preprint’ from a ‘paper’?” Nothing. Both preprint publications and formal publications are papers. Reviewing of both publications, whatever form it takes, is “post publication peer review.” On the other hand, “pre-publication peer review” is something done privately, usually without the feedback being made public (“published”). It is usually carried out at an editor’s request by someone he/she has chosen and is limited by the editor’s knowledge of the available “experts” in a field, their willingness to donate this expertise, and its quality. When other “experts” feel, post-publication, that such quality is missing, then they may engage in “post-publication peer review.” This process was once greatly assisted by the NCBI’s now-defunct PubMed Commons (that required some degree of accreditation) and is now assisted by PubPeer (no accreditation needed).

Thanks Donald, I think you’re right in terms of the terminology — the question isn’t the difference between a “preprint” and a “paper” but instead a “preprint” and a “published paper”, and I’ve amended my language in the introduction above to note this.

But my question still stands — we have initiatives where peer review is being carried out on a preprint “at an editor’s request by someone he/she has chosen and is limited by the editor’s knowledge of the available “experts” in the field, their willingness to donate this expertise, and its quality.” That review is made public (“published” as you note). Is this still a preprint? What if those same reviews are sent along to a journal and used to immediately accept the paper? When did it stop being a preprint?

Thanks David, I’m interested to know if there’s any real hard data, trending data or insights on how many preprints are submitted to journals first and then published as preprints via the journal submission process (this can be publisher focussed preprints JMIR/Springer Nature Research Square, or publisher agreements with bioRxiv/medRxiv and the likes) while the peer review process is carried out, and how many preprints are submitted directly as a preprint without a direct journal submission, the author may of course have a journal in mind but wants to publish their research early as a preprint and receive feedback.

Publishers have brought in policies to encourage the publication of a preprint on submission, but is anyone aware of institutions or funders who have mandated or strongly encouraged authors to have a preprint first policy, process and mindset?

Thanks for revisiting this issue, David. I respond as someone who is involved with both a preprint server (medRxiv) and a journal that undertakes open peer review with posting of original manuscripts and peer review reports alongside the revised and finished published article (The BMJ).

Personally, I preserve the term ‘preprint server’ to mean something that *only* delivers an author-submitted version of a manuscript and doesn’t also provide peer-reviewed and edited content. In the same vein, I use ‘preprint’ to mean ‘what the author wrote and shared, without the intervention of editors or formal peer reviewers’. And I see a ‘published journal article’ as one that has had identifiable intervention from someone independent of the authors: editor(s), peer reviewer(s) and so on.

An interesting note about the F1000 Research platform and related offerings is that they do distinguish between what I would call preprints and published articles, by posting the latter with indexing services such as PubMed. What I don’t know how to describe are the pieces that are posted on F1000 Research, go through one round of peer review but then are never revised to become formal published articles (full disclosure: I am the author of one such piece). I tend to refer to this as a preprint still, as it hasn’t been ratified by peer review, but would love to know what terminology is recommended in this case.

Things get even more complicated when you think of a manuscript posted as a preprint then submitted to a journal. The article goes through the full peer review process and gets rejected. The authors revise the preprint, based on the feedback from that full peer review process, and re-post it as a new version of the preprint on the preprint server, while submitting the revised version to a different journal. That revised preprint has clearly had the “intervention of editors or formal peer reviewers” yet we probably would not consider it “published”.

You’re right, of course David. Perhaps one should say it is about who is taking responsibility for the content: when it is a preprint, that is only the authors, whoever else has commented or made other input. When it is published in a journal, the journal editors take some level of responsibility.

Interesting idea — is it the vouching that makes the difference? Journal X is willing to put their reputation behind this manuscript and state that they believe it is of the journal’s standard of quality.

I’d note that most preprint servers also do some sort of screening – perhaps authorship, for being in scope, for method, etc. Which is somehow, it if often asserted, absolutely not a review or editorial process?

Yep. Still trying to figure out where the line is drawn — is what medRxiv does any less than what F1000 Research does? Why is the former considered a preprint, but not the latter?

And with that we just got to the “considered by who” component of pretty much all conversations about most terminology in scholarly communications!

There does seem to be an increasing blurring of lines between preprints and publications, the one established distinction being peer review status; but as you have outlined here, post-publication peer review has potential for further confusion especially as a preprint could be considered a “publication” insofar as it has an assigned DOI. As some journals move toward open/transparent peer review and others move in the opposite direction toward increased anonymity and blinding (there are pros and cons to both) there doesn’t seem to be a consensus on what model best serves the research community. Whatever form it takes, peer review is not up for debate as a sine qua non for trusted research, so those like the Economist author who asserts the preprint servers can (and even should) make journals obsolete are pushing an agenda out of touch with reality. I’m all for making the publication workflow more flexible to alternative modes of dissemination, but to your point, we need clarity on terminology and classification of preprints, journals, and models that blur the lines between them.

Preprints are publications. Articles are publications. We could just admit that we’ve evolved to believe that iterative publication of the same paper is a good thing rather than trying to maintain the tortured notion that somehow a publication (preprint) isn’t actually a publication? (Also interesting … many – most? – journal articles are also pre-print in that the actual printing takes place by the reader deciding to make the digital PDF into a paper replica … which is usually a degraded version of the digital as citations etc. are increasingly optimized for digital delivery rather than print, but I digress…)?

Sure, but that’s arguing semantics. Use whatever word you want, but isn’t there a dividing line between what we consider a working manuscript and what we consider to be a vetted and finalized article? Where is that line and when in the process does it occur?

I absolutely agree there are differences. I think we’d be far better off though by not trying to label one version the “publication” … because that’s what gets us into the semantics game. I’d note that JAV (NISO) — currently under revision — specifically does not use preprint either because there are so many different versions of the article that are called the preprint. FWIW, I think we’re going to see a real uptake in JAV tag use in the coming years for this and other reasons…

P.S. You asked us to discuss semantics!

Fair, but I’m not asking about the specific terminology that’s used, rather the concept that the word confers — whatever word one uses, one version is different from the other, but the lines between them are blurring. I want to talk about the line, not the words used to describe the things on either side of the line.

Here are a couple of info tidbits that may be helpful: (1) Preprints account for about 3% of the total number of scholarly articles published each year (https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1008565); (2) In general, preprints are mostly research articles posted online to generate feedback before submitting to a journal, or to claim discovery. Except for a few fields, preprints are most often not an “end-state” in publishing; (3) There are, on average, significant differences between preprints and journal articles in terms of peer review, quality, speed, citation rates, discoverability, accessibility, research impact, career impact and more; and (4) In the field of epidemiology, two-thirds of preprints posted before 2017 were later published in peer-reviewed journals within 12-18 months (see https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.45133; this finding may or may not be generalizable to all STM research). Preprints host a “rough draft” of research while researchers look for a publisher and wade through rejections. Across all kinds of journals, the average rejection rate of articles is 60-65% (https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2019.jul.07). Individual rates vary widely by journal, ranging from 0-90% and higher. About 20% of papers get rejected before peer review for being out of scope, among other reasons (see https://bit.ly/2YnYoVv). Almost two-thirds of research articles are rejected at least once (see https://bit.ly/2YkPpo2), but most eventually get published somewhere.

For more details, see OSI Infographic 2.0 at https://bit.ly/3hIn4C7.