One of the benefits of hypertext in a connected digital environment is the ability to interlink documents. This was part of the hyper-text focused vision of the internet that Tim Berners-Lee was trying to create in the 1990s when he developed the World Wide Web. At the time, there were other prototypes and products that were more robust visions of what hypertext could do, including Apple’s HyperCard product, the Microcosm hypermedia system developed by Wendy Hall and a team at Southampton University and Ben Schneiderman’s HyperTies system. There was a great deal of excitement around these ideas that originated from Ted Nelson’s (unrealized) vision of digital communications that he proposed in the 1960s.

Initial experiments and products that were built in the late 1980s and 1990s around hypertext philosophies allowed anyone to create a link from a document. Some of those at the time thought HTML and the WWW that developed based on its principles was a step backward in some respects because the links that were created were only unidirectional and other hypertext features such as annotation were not included (among other criticisms). This means that only a site’s administrators (or eventually those with write-access, in the case of wikis and other “Web 2.0” tools that developed later) could insert a link onto a page. It was the sole responsibility of the author to curate and maintain the content. In fact this curation role — and the principle of the primacy of the author/publisher — created a number of subsequent problems on the Internet that we’re dealing with today, such as link rot, website preservation, and retractions.

Apart from having to deal with the unfortunate implications of these infrastructure decisions, today much of this is historical, but important, context. A few weeks ago, Ross Mounce posted the following complaint on twitter:

Today in things I don’t like about Elsevier…

Has anyone noticed how they’ve been adding embedded hyperlinks to their ‘Topic Pages’ within HTML pages of peer-reviewed articles? The authors surely didn’t put them in.

Do paying subscribers get to say “no” to this? pic.twitter.com/nnNSOS9BdQ

— R⓪ss Mounce (@rmounce) August 20, 2021

====

the example given in the screenshot is here: https://t.co/j6oTibDl0k

They are trying to get people to use their failed ‘Topic Pages’ project. It’s not going to work. It’ll only annoy people (like me!). But sure, make it an option to ‘turn ON’ if and only if users want it.

— R⓪ss Mounce (@rmounce) August 20, 2021

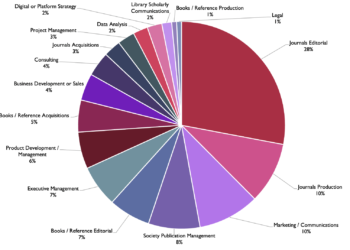

These tweets raise some important questions worthy of some thoughtful consideration. Let’s start with the fact that more and more publishers and site administrators are doing this same thing with content all the time. Probably every large news site you visit has these embedded links that were not inserted by the author, as well as at a variety of scholarly publishers’ sites. A number of semantic enrichment and natural-language-processing entity extraction and linking tools are available and widely deployed by companies and organizations around the web. Because much of this work can be highly automated and is generally quite accurate (though by no means perfect), publishers see this as a useful value-added service for readers that is easily deployed. One might expect that most of these same publishers have done a ROI analysis of these tool’s effectiveness, which likely show the enrichment increases user’s time on the site, click-through counts to related pages, and likely overall user satisfaction. If this weren’t the case, I expect that publishers would halt this investment.

Reacting to the tweet, the NISO team had a lively discussion about what are the purposes and the values of linking versus citation. We discussed whether this enrichment was equivalent to citation or, as Mounce claimed, if this type of enrichment was a type of editorializing on an author’s work. While the two are related, links are not citations, particularly in the way citations are used in scholarly literature. The strongest evidence of this is that researchers have long been citing websites and every citation style manual includes a model for referencing a website in either a bibliography or in references in formal publication. A paper might include both links and citations. Most readers would very easily distinguish between the two. Furthermore, many of the organizations embedding these links format them differently than they do either links or citations. In the example noted by Mounce, the embedded links are displayed as links (underlined but as grey-colored type) while the citations are differentiated according to Elsevier’s house style (in parentheses and in blue type). Other publishers do similar things to distinguish this semantic linking. Ensuring that there is a clear distinction between the two in the display is likely the best practice when applying this technology.

In part, Mounce’s critique seems a knee-jerk reaction to something a large publisher is doing. Let’s start with the premise that Elsevier is seeking to get ancillary subscription revenue by linking to related content that it was selling. Perhaps this is useful to the reader, perhaps not. However, is this so problematic? I expect that a large company like Elsevier has done sufficient user testing on this presentation that it is both not intrusive to the majority of readers, and it is providing a useful service to some subset of readers, such that Elsevier is continuing to deploy it. Beyond this, a process to semantically enrich content is being advanced by NISO to support even more of this type of document linking. Other publishers are certainly headed in this direction. However, let’s not simply define what is acceptable by what everyone is doing.

Beyond this, let’s also consider for a moment the licensing question at play here as well. This particular article is published under a CC-BY license. That being the case, even if the article was not published by Elsevier in an Elsevier journal, by agreeing to distribute their content under that license, the authors are explicitly agreeing to allow this type of enrichment. In fact ANY enrichment of any kind is acceptable, so long as the original work is attributed. That is exactly what the CC-BY license was designed to allow. As strong a proponent of open access (OA) publishing as Ross is, I’m surprised he gets this aspect of OA publishing so wrong. Creative Commons licenses that are not explicitly “Non-Commercial” (i.e., CC-BY-NC, for example) foster this kind of commercial reuse, by removing the license barriers to repurposing content for commercial use, such as selling other products. There has been a robust argument that education can be a commercial use, which led to the broad advocacy for CC-BY for academic materials to remove even this potential barrier to educational or scholarly reuse.

Mounce’s problem seems to be that Elsevier is trying to sell published content. Yet if the authors objected to this type of reuse, or if the OA movement in general objected to commercial reuse, they could have thrown their considerable advocacy weight behind a different version of CC license. I have long argued that authors should exert more control over their copyright and apply more nuance to the licenses that they give away or retain. Authors will generally follow whatever policy is driven by their institution, funding body, or publisher editorial policy. Most of us follow the path of least resistance, but I digress.

More importantly, since an increasing number of content publishers and distributors are providing this semantic enrichment, it is probably valuable to consider when it crosses a line and when such enrichment is fine. We can all agree that linking to terminology to resources like GenBank sequences, or Oxford English Dictionary definitions which provide more detailed information is acceptable. Linking to curated resources (as Elsevier has done), public information pages, or Wikipedia pages might be a next level of curation, which is more or less objectionable. If there were an established resource where protocols were described in detail (something like what protocols.io is building) and a publisher were to link to a protocol hosted there, but was not embedded in the paper by the author, that might well be crossing a line. How would the publisher know that the process the author undertook is exactly what is being linked by an NLP reading of a protocol? One could take this application even further into troubling territory. There is a line that needs to be defined somewhere. It will probably be best if we collectively don’t leave the definition of that line up to the machines.

Discussion

14 Thoughts on "Where Does Enhancement End and Citation Begin?"

I just want to comment that the use of “citation” is ambiguous and confusing. I know I’m fighting an uphill battle here, because the use of “citation” to mean a work being cited as a reference by another work goes back decades. But as a librarian, I see the consequences of this confusion all the time in terms of users making sense of functionality in databases and even in training.

What we put at the end of the articles we write to properly credit the works we use are “cited references”. The APA/MLA/etc. formatted description of our own article is a “citation”. And yes, we use “citations” to indicate the specific cited references in a standardized format, but when talking about them in their role as references to other works used from a given work that used them, rather than their own bibliographic data, I encourage everyone to adopt this distinction.

Great post! I think that this type of direct enrichment to the article text is invasive, whether it was done by machines or by the publisher and without the author’s consent. I’m not sure that the styling of the link to differentiate them from the author’s cited references does enough to help the average reader distinguish between the two.

In addition, I think there where some great comments on the use of the term “citation” and would like to ask a couple questions:

1) Regarding the links to the references section that the author supplies with their manuscript –

are these picked up by services automatically, so the referenced articles can provide a CITED-BY section within their own display?

2) How does the actionable link “CITE” relate to this? Is that just a tool to extract a formatted snippet when you are building your own bibliography? Or is this action picked up by some automated service as mentioned in question #1?

thanks

You might want to look into the Crossref Cited By service, https://www.crossref.org/services/cited-by/

This is an optional service (not required to participate in their overall DOI system) that is attempting to do what I think you’re talking about. But as with DOI itself, for it to work requires publisher participation and commitment to consistently use and maintain the metadata across their content.

Given its past performance and behavior, I don’t see any reason to presume that Elsevier tested its linking feature with authors or readers in terms of serving them; the decision was likely made by the marketing department as an attempt to increase revenue. And I worry about what exactly will be linked to, as this practice is likely to come to be viewed as providing THE relevant additional information rather than SOME relevant additional information.

As for the idea that the authors don’t care about licensing because they didn’t say enough, witness Plan S: Who is listening to the authors on that front? An entire eco-system is being forcibly altered by a small group of people whose primary function is funding research, not producing it nor publishing it. As someone who works in the latter, I can tell you that the rush to full-blown OA has caused more than a bit of consternation among the authors and their organizations; even the ones who are handling it well are mostly playing catch-up. As are most of the publishers.

What a thoughtful piece in the Kitchen today!

The meaning of a reference (or citation) has a long history of debate in scholarship. I think Blaise Cronin summed it up best in his 1984 book:

Citation is a private process with a public face. Therefore, any attempt to understand the nature of citations is conjecture (p.28) [1]

Nevertheless, you hit upon a more fundamental point in the end of your piece:

It will probably be best if we collectively don’t leave the definition of that line up to the machines.

While we cannot hold machines accountable for the links they automatically insert into a piece of text, these algorithms were designed by humans and therefore are imbued with human values and intention. The business executives at Elsevier who decided to implement these systems also made conscious decisions to use them, weighing the costs and benefits to the company while (hopefully) taking into consideration the value to the reader and risks to the author. Technologists will argue that human curation is simply too costly and that machines can do the job better and faster. What they miss, however, is that a machine (unlike an editor) doesn’t care if an author is outraged from this process and never signed off on the final version. I’m not wholly against the idea of automatically embedding referencing lists inside a published document; I do find it problematic if the author did not agree to this kind of post-acceptance editing and does not have a chance to change/remove links if the machine really blunders.

In sum, someone has to be responsible and accountable over the machine.

Citation:

1. Cronin B. The citation process: the role and significance of citations in scientific communication London: Taylor Graham, 1984. *

In terms of human oversight of the machine, I would think that ideally the algorithms that insert the linking should be run pre-acceptance, for an accuracy check during the final stages of peer review. Downside is added burden on editors/authors. However, this would not only prevent lines from being crossed but would also likely give the publisher a much clearer view into whether their authors are indeed fine—or even aware—that such enrichment is happening.

Elsevier’s adding hypertexts to (hopefully) related content seems mild compared to Wiley’s recent practice of adding ads to articles’ versions of record. To me, the publishers version of record should be sacrosanct. Otherwise, what is a VOR? Adding a new first page to the VORs with advertising is beyond gauche, IMHO.

This post is excellent and it matches perfectly with the scope of the APE 2022 Conference next January in Berlin. Our motto: The Future of the Permanent Record. When everything is open, who controls the noise in the system (who wrote: noise in the system?

Greetings from Berlin

Intersting post. Actually Elsevier’s practice with the link enriching is not dependent on the licensing.

Here is an article with enriching and CC BY-NC-ND license from the same journal:

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2021.04.006

And one with traditional copyright (although freely available to read at least when I tested)

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2021.07.625

The added links can also be found in non-CC BY-licensed Elsevier articles.

CC BY-NC-ND: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2021.04.006

Traditional copyright: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2021.07.625

I think Ross has raised a very important issue. It is worth noting that publishers cannot contract away the moral rights of the author and the moral rights are based in legislation – they are not simply a concept to be waived away. In Australia the rights are:

Right of attribution: this is the right of an author to be identified and named as the author of his/her work;

Right against false attribution: this is the right of an author to stop someone else being credited as the author of their work; and

Right of integrity: this is the right of an author to ensure that his/her work is not subjected to derogatory treatment which is any act in relation to the work that is in any manner harmful to the author’s honour or reputation.

I would think Ross had identified an area that is directly relevant to the third right. It is important to in essence ensure authors integrity and inserting outer material could arguably fail to meet that condition.

No amount of user testing would change this legal requirement. At the very least consent would be required before the insertion of other references/links.

In my understanding, one of the rationales for the topic pages is that not every reader of a scientific article is familiar with every concept discussed in that article. If you are a specialist, terms like “vergence” and “electrodermal activity” in the example cited may be fully understood. However, for a student, a lay person reading a health-related article, or even a research scientist in a different area, an efficient way to check on the meaning of these terms and understand them more deeply may be quite valuable. Indeed, one of the primary arguments of the open access movement is making the research literature more accessible and available to all potential readers. Surely part of this is trying to ensure that readers actually understand what they are reading. In addition, we should give some credit to readers that they can distinguish between a primary text and a secondary source of information. When I click on a Wikipedia link to learn more information on say, the New York City Subway, I know that it’s not a substitute for reading a history of New York City, nor is in it direct reference being made by the author of the original web page that I came from.

Lots of food for thought and a rich topic for discussion. Thanks, Todd!

I realize the Elsevier example was just a seed, but within a month of the topic pages release, our Elsevier rep spent 20 minutes of a meeting earmarked for an entirely different matter to intro the topic pages followed by an upsell of Elsevier’s book packages. While the topic pages may provide useful context for lay readers, I see them partly as an attempt by Elsevier to market their ebook portfolio, an area where they’re definitely playing catch-up (e.g. Springer has more robust offerings and has a clear leg up here).

I still haven’t formulated any crisp thoughts on Todd’s final words:

There is a line that needs to be defined somewhere. It will probably be best if we collectively don’t leave the definition of that line up to the machines.

But I thought I’d share a few early examples of semantic enhancement:

SCILITE: For skimming and understanding life sciences content, Europe PMC’s SciLite feature is noteworthy. SciLite consolidates various text-mined annotations and displays those annotations on research articles browsed within Europe PMC webpages. For an example, click ‘Annotations’ in the right rail of this article: http://europepmc.org/article/PMC/5598042

UTOPIA DOCS was an early example of semantic enrichment delivered through a web-enabled, bioscience-focused PDF reader. The Utopia Docs desktop app/bookmarklet was a 2012 spinout from the University of Manchester that is no longer active. (View a 5-minute demo at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1M26DRlZwSM.) Users could explore words or phrases by in-text selection or search. This returned a right-rail panel with results from various sources such as Wikipedia, Protein Data Bank structures, related recent articles from PubMed, related laboratory resources, and up-to-the-minute news from SciBite (SciBite is a UK-based semantic AI company that was acquired by Elsevier).