It certainly isn’t fun to be called out for one’s errors. Each of the Chefs on the Scholarly Kitchen can appreciate that, as we all have been wrong at one point or another. Some errors are small, some could be considered more significant. What is important is how we react to those errors. But what about times when we don’t know which approach is most appropriate and we test things to determine the best path forward? If you try something, fail, and then use those learnings to improve, that’s not exactly an error. It’s part of a methodology. An important part of that methodology is the willingness to spot the least viable approach and pivot. It also requires a willingness to take risk and incorporate that risk taking into our approach to running our businesses. A core element of that methodology is focusing on the needs of users, and ideally interacting with them in this process.

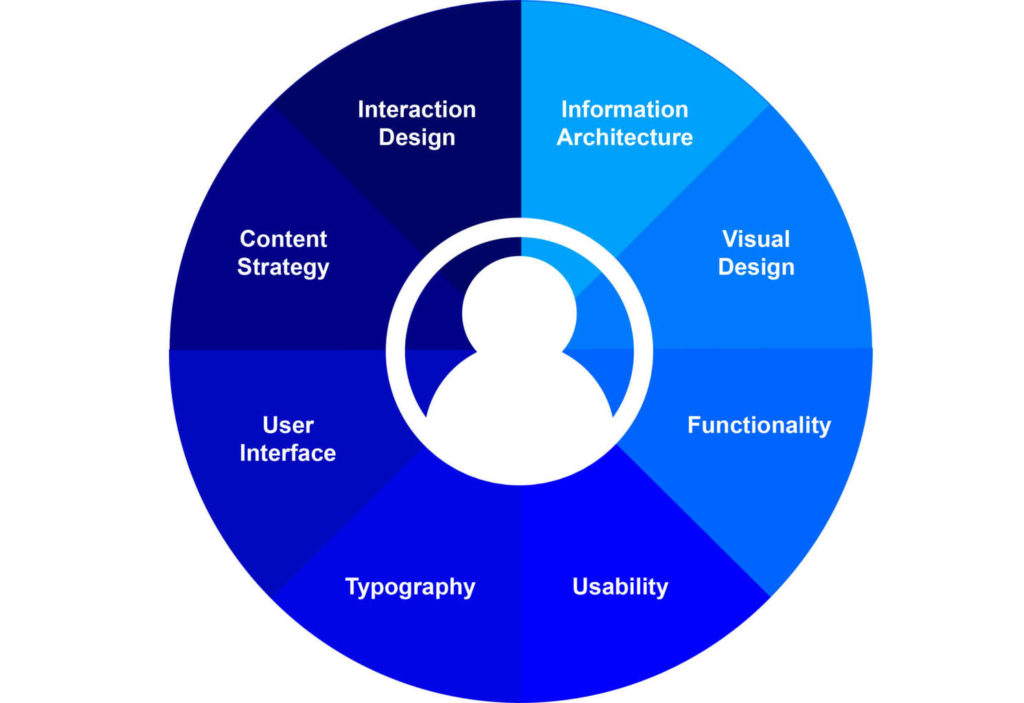

Last week during a NISO virtual conference on approaches to fixing the user experience, I had the opportunity to have a talk with Sam Herbert at 67 Bricks to discuss putting the user first in the design of technology and services in our community. Each of us, regardless of whether we are at a publisher, a software provider, a library, a university, a government agency, or an archive, have users that we serve. We might call them patrons, or customers, or students, or even just the public, but every one of us has a community we serve. We think of these people regularly, in terms of our customer support, in terms of our finances, in terms of fulfilling their requests or demands, or in terms of enlarging the pool of those that use our services. But how often, when designing our products, services, or offerings, are we putting the users in the center of those decisions?

Increasingly, the tools exist to engage with users, to iterate quickly, test the results, and then adapt to the new knowledge. We can leverage the benefits of digital distribution to constantly tweak and improve the user experience in a way that simply was not possible in an analog environment. Many organizations have incorporated some elements of user experience study or user-focused design into their design processes, which has been positive. But it’s not clear how deeply embedded this philosophy is as we consider our approach to our role serving the scholarly communications processes writ large. And this is despite some ample evidence that user-focused analysis should serve publishers well.

One of the points that Sam raised was that publishing has historically been a community that is averse to risk taking, especially when it comes to product development. When the analog output of our work into the marketplace is unchangeable, and the potential risks of getting it wrong are significant, it breeds a cautious attitude. However, in a digital environment, we can test new approaches, new designs, or new forms much more easily to see if they suit user needs or expectations. We can quantifiably assess if they work and then iteratively improve them in a timescale measured in days or weeks, not years.

The notion that a minimum viable product could be released into the world is frightening for publishers, particularly those of us who were raised in a print environment of distribution. If one is going to produce 10,000, or 50,000 or 100,000 or more copies of a printed edition of a publication, you don’t have the opportunity to go back and fix an error. Or if you have to fix that error it will get very expensive, very quickly. Perhaps an editorial error can be fixed in the next print run, if there is one. More likely than not, that error remains in print forever and there isn’t a re-do. So those involved in the process of putting publications together were deeply invested in getting things as close to perfect as possible. Publishers invested in vetting authors, editing, copyediting, and reviewing content before it went into production. Proofs were reviewed and revised, hopefully catching each missed comma or unclear pronoun. In this environment, experimentation in product forms or approaches were very seldom tried and slow to gain traction if they were.

Today, however, authors are much more eager to get content out the door and distributed, and seemingly value less and less the careful curation of previous eras. The latest news or research result needs to be shared today, this moment. This has been compounded by the exigencies of the pandemic in some domains. But we are bound by modes of thinking around form, structure, and approach that inhibit addressing the core value that a user seeks. When a researcher is reading through several dozen papers to identify the appropriate method, there is a specific goal in mind and the model of text-based unstructured methods reporting isn’t necessarily the best approach to serving the user’s goals.

An experimental mindset has existed in many of the start-ups that have developed in our community over the years. Advances in some non-textual forms have advanced by those new market service providers, especially among repositories, video services, and protocols providers. Experimentation around search, and scientific workflow management are interesting areas of growth. A few publishers have adopted this user-centered approach in their product development, but seemingly most of the significant experimentation is taking place outside of traditional outlets.

Furthermore, the authors whom publishers serve are also conservative in their approach to sharing their results. If one’s career success is based on the contributions to the scholarly record as determined by the first handful of papers the author produces, she would be much less likely to risk a new approach to communicating her findings. Those later in their careers might have the freedom to experiment, but often by that time, they’ve concentrated their workflows to push toward established output forms. This further limits the willingness and ability of established players to experiment and shift their services toward something that might better suit the users’ goals.

It takes a lot of fortitude to tweak those things that are core to one’s business, especially if it appears at first glance that those approaches are working. Many of the approaches to transformation of scholarly communications seem to be driven by not by first understanding the users and their needs, but rather by estimations and presumptions by providers about what they think users want. Instead of iterating toward a user goal, some transformations are driven by a top-down vision of what the users should want. Putting the user at the center of our thinking could lead to better approaches and better outcomes.

Discussion

1 Thought on "Iterative Development, User-centered Design, and the Fear of Getting it Wrong in Publishing"

The dirty little secret is for most publications nobody wants a version 2.0. It’s good enough. Sure, there are some exceptions where they come out with the 20th anniversary edition of a monograph, but think about how few research teams stay together after a particular study published in a medical journal. I don’t think print is holding folks back, but rather time. It takes time even to add color charts to an article. And now researchers are supposed to add code that executes, manipulable datasets, sound and video. Every time someone says we’ll be constantly adding new features, I think, do you have the funding up-front to add new features for the next 20 years.