Editor’s Note: Today’s post is by Roy Kaufman. Roy is Managing Director of both Business Development and Government Relations for Copyright Clearance Center.

In the aftermath of Brexit, many publishers were wondering if the UK — with its strong tradition of supporting the rights of publishers, authors, and artists — would provide another voice in defense of copyright. Having just read a new report from the UK’s Intellectual Property Office (IPO), this tradition is at serious risk.

In a much-anticipated report, the UK Intellectual Property Office recommends a major rewriting of UK copyright law, delivering the future of copyright to those using AI and damaging the present and future financial interests of publishers, authors, journalists, and musicians among others. The changes would also hinder continued investments by rightsholders in the costly processes of data cleansing, content normalization, tagging, and enrichment which are needed to make content fit-for-purpose for mining and AI, paradoxically hindering at least some of the technological advancements the IPO seeks to encourage.

History

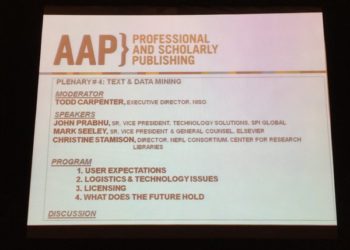

By way of background, the EU, as part of its Digital Single Market Copyright Directive, looked at the then-extant UK copyright exception for the making of copies of copyrightable works to perform text and data mining (TDM) in a non-commercial context. The EU decided to create a roughly equivalent non-commercial exception (Article 3), along with a broader exception for commercial and non-commercial TDM, subject to a rightsholder opt-out (Article 4). I have somewhat nerdy international copyright lawyer problems with the exception, especially as I believe it introduced a “formality” to the enjoyment of a right which is impermissible under the Berne Convention. On the other hand, it clearly distinguishes those with an economic copyright interest from those without one while setting forth two clear paths for reuse: licensing for the former, copyright exception for the latter. By creating an opt-out, the Directive mitigates the risk of a more serious Berne Convention problem; namely a violation of the 3-Step Test.

UK to EU to UK

No longer bound to or by the EU – but guided by the new Directive—the UK decided to review possible changes to its laws. The options ranged from no change to UK law, to improving the licensing environment, to offering new copyright exceptions. After receiving evidence from rightsholders, who generally favored either increased governmental licensing support or no changes (implicitly or explicitly indicating support for UK’s current non-commercial exception), and presumably from at least some others who disagreed, the IPO decided on an extreme exception. Under the IPO’s proposal, “Rights holders will no longer be able to charge for UK licences for TDM and will not be able to contract or opt-out of the exception. The new provision may also affect those who have built partial business models around data licensing.” (Full disclosure, my employer CCC has built a business model around this for research intensive industries such as pharma and chemical. I don’t think I would call it “partial.”) So, if you have invested in enriching your content and in accessible APIs for mining and AI, thank you very much, but don’t expect to recoup that investment.

Should there be any doubt that this was simply a negation of rights, the IPO stated, “The benefits will be reducing the time needed to obtain permission from multiple rights holders and no licence fee to pay.” In this way the law will go much further than US fair use (which looks closely at lost market harm such as licensing revenue — actual and potential) and the laws of the EU, which allow opt-out. The IPO’s proposed exception is much closer to that passed very recently by Singapore, a country with fewer media companies, publishing companies, and learned societies to feel the brunt of the exception. (The IPO also referenced an exception in Japanese law, which is complicated but narrower than the IPO’s proposal.)

Beware the Fig Leaf

The IPO tells us: “However, rights holders will still have safeguards to protect their content. The main safeguard will be the requirement for lawful access. That is, rights holders can choose the platform where they make their works available, including charging for access via subscription or single charge. They will also be able to take measures to ensure the integrity and security of their systems.” This text follows the statement above, which I repeat: “Rights holders will no longer be able to charge for UK licences for TDM and will not be able to contract or opt-out of the exception.” In other words, as long as a user receives lawful access, including a personal subscription or free access through membership, all TDM and AI is fair game. Only pirated content is excluded.

Impacts

If an exception as recommended passes, news organizations will feel the brunt first. This exception will accelerate revenue decline and reduced output. After all, one of the few bright spots for news revenues in recent years has been licensing TDM and AI for fintech, marketing technology (martech), banking, and hedge funds. I am loath to declare all news content buyers “winners” here, however. While a hedge fund would prefer not to pay to access high quality news, loss of AI/TDM licensing revenues is likely to push more news sources over the brink. The need remains for high quality, validated news unavailable from social media. Even if outlets do not close, having less money for reporting will reduce available content.

News publishers will face a double threat, insofar as basic news stories are often already written by AI. The exception would allow third parties to use a publisher’s content to train that publisher’s journalist-free competition. And, to take the irony further, the output from unlicensed use of the underlying works will almost certainly be offered for license by the user.

The impact on journal publishing is harder to predict but will be lasting, given the rapidly increasing importance of TDM and AI. Today, corporations do pay for the right to mine content, especially when content has been tagged and enriched, so that revenue is obviously at risk.

The weakening of copyright protection may also drive publishers further into open access (OA) business models. OA shifts the costs of the publication system from the user to the author, and in the case of the IPO proposal, from corporate users to authors, institutions, and funders. Of course, said authors, institutions, and funders may feel less than enthusiastic about making up for publishers’ additional lost corporate revenues with increased APCs and author charges.

Other questions come to mind: Will publishers invest less in enriching content and making it available for AI? Will they move UK-based servers to other countries with more favorable laws and enforceable contractual restrictions? Will they rethink policies on allowing content into repositories they do not control to avoid “good enough” lawful copies replacing final versions for AI?

What next?

One response on the table for rightsholders if the exception passes into law is Judicial Review by UK courts. In 2015, the UK music industry successfully sued the UK government to block a private copying exception. The music industry has already fired a shot about the new TDM exception. Given music’s prior success with Judicial Review, the UK government may take that industry’s objections seriously.

With that said, it is currently unclear how the UK Government plans to implement this exception, or indeed if it will. In the short gap between issuance of the IPO Report and the resignation of Boris Johnson and many of his ministers, rightsholders’ groups seem to have detected a sympathetic ear at the UK political level. Introduction of a bill will likely be delayed until a new Prime Minister assumes control. Whether that person is interested in controversial legislation such as this is anyone’s guess.

Discussion

1 Thought on "Guest Post — UK Law and Artificial Intelligence: UK IPO Issues Problematic Report"

Hi Roy,

Thanks for the informative post. I am just wondering what legal access means in the context of mining music for data. I understand that data users can purchase music and subscribe to streaming services, by purchasing music they could then convert audio data to MIDI data, clean it and what not and then use it in a training data set, but is it also considered legal access to subscribe to say Spotify or YouTube and then use converters to obtain MIDI data? My reason for asking is that obviously music rights holders are beholden to making their work publicly available!

Also, does this mean that AI companies worldwide are able to mine data (e.g., music) that is registered/published in the UK without infringing and without a licence, or is it just UK companies and UK data? Or UK companies are free to mine data obtained from any territory without consequence… so long as they have lawful access? So a UK company could mine data from all Drake tracks, for example, so long as they have lawful access, even though Drake is a US artist.

This is a minefield! Thanks in advance!