Editor’s Note: Today’s post is by Dylan Ruediger. Dylan is a senior analyst at Ithaka S+R, where he focuses on exploring research practices and communities. He is currently an SSP fellow.

While the full impact of last week’s announcement of major changes in federal policy regarding public access to the results of federally funded research will depend heavily on how federal agencies implement it, it does seem clear that it will accelerate momentum towards open access across the industry and likely be a “game changer for scholarly publishing.” Those sections of the memo requiring the immediate deposit of research data underlying publications are of at least equal importance. However, with much of the media coverage focused on

journal articles and academic publishing models, the changes to federal data sharing policies outlined in the Nelson Memo have been comparatively underexplored. Statements from major organizations such as the AAU or AAAS, for example, mention data either in passing or not at all. Yet the new data policies will meaningfully affect researchers, have significant implications for the business model of generalist repositories, and may provide hope for domain repositories, many of which currently struggle to find financial sustainability as the grant-funding that created them dries up.

Changes to current policies

Current federal data sharing policies are based on the 2013 Holdren Memo. The Holdren Memo is broadly similar in its aims to the Nelson Memo, but has several key differences both in overall scope and in the language of specific sections.

The most immediate difference is that the Holdren Memo applied only to agencies with annual research and development budgets over $100 million. The new policy will apply to all federally funded research, regardless of the size of the grant or the sponsoring agency, and thus will impact a wider range of scholars. One key impact is that humanists will be subject to the policy en masse for the first time, at least those who receive funding from the the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities. (The NEH’s Office of Digital Humanities is the only branch of the agency that currently requires a data management plan specifying plans to share research data.) Adopting data sharing policies in humanities and arts fields will be a significant challenge as they have little cultural tradition of data sharing or even a consensus about what constitutes “data.” Will it only include quantitative materials or also interview transcripts? Will it include archival records? What about text corpora used for analysis? The federal government seems to share this confusion: though the data sharing policies clearly apply to NEH and NEA, the Nelson Memo consistently refers to “scientific data,” defined as the “recorded factual material commonly accepted in the scientific community as of sufficient quality to validate and replicate research findings.” It does not seem that very many humanists were involved in thinking through the OSTP policy guidance.

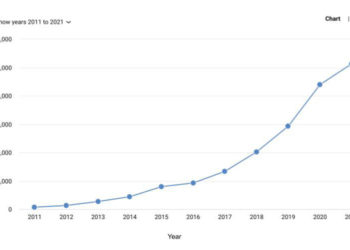

But the changes to data sharing policies will by no means be limited to humanists. The Nelson Memo includes language that will likely affect STEM researchers funded by the NSF, NIH, and other agencies subject to the Holdren Memo. Current policy applies only to research data “used to support scholarly publications,” and only asked agencies for plans to “maximize” public access, rather than absolutely requiring public access. In contrast, the Nelson Memo calls for immediate public access to data supporting publications, and asks agencies to develop “approaches and timelines for sharing other federally funded scientific data that are not associated with peer-reviewed scholarly publications.” The timeline for sharing these data seems further in the future than the overall timeline outlined in the Memo (which requires implementation of new policies by 2026). However, it clearly points to the likelihood that all data resulting from federal funding will someday be subject to preservation requirements. If implemented, these changes will massively expand the quantity of data subject to federal data sharing requirements. This would be a very expensive proposition given the amount of data that researchers in data-intensive fields create. It also has the potential to exacerbate the resentments that we have previously documented among researchers about the amount of data they feel compelled to curate and preserve to FAIR compliant standards.

Finally, there is a subtle but potentially significant tonal shift about the costs associated with data sharing. The Holdren Memo calls for improving the accessibility of federally funded data and allows researchers to include the costs of doing so in their funding requests. However, it also directed agencies to balance financial and administrative costs of long-term preservation against the relative value of public access. Agencies have adopted different approaches to finding this balance. The NSF has taken a somewhat conservative approach. Its policy on data sharing emphasizes the expectation that researchers share their data but “at no more than incremental cost and within a reasonable time.” In contrast, the NIH’s new data sharing policy places emphasis on “maximizing” data sharing (though still not requiring it). The Nelson Memo adopts the latter phrase, moving the Overton window towards a larger commitment to prioritizing sharing over minimizing costs. However, it does not provide for additional funds to support that commitment, a decision that may end up limiting compliance by researchers and blunting the effects of the new policies.

A third key difference between current and new federal policies is the timeframe in which data should be shared. The Holdren Memo does not specify when data should be shared. As we have seen, the NSF currently allows for a leisurely “reasonable” time frame for making data available. The Nelson Memo includes much more specific language that data should, in most cases, be publicly and freely available at the time of publication. This will place a substantial burden on researchers, particularly in fields which require quick and frequent publication of results.

Implications for Researchers

Despite considerable investments and growing mandates from funders, the actual practice of sharing data has been unevenly adopted by researchers. In many fields, the incentive structures academics respond to do not place a high value on data sharing. Even in medical fields, where data sharing is comparatively well established, only about half of faculty reported regularly or even occasionally sharing research data. Researcher’s attitudes towards data publication are complex: even as familiarity and compliance with FAIR standards grows, concerns with data sharing do as well. Researchers are increasingly worried about misuse of data, lack of appropriate credit, and uncertainty around data licensing, and they remain wary of the financial costs and labor involved in preparing data for deposit.

Each of these concerns point to the essential role that research cultures play in data sharing. Indeed, even as the technical infrastructure to enable data deposit and reuse has matured, the cultural infrastructure that encourages researchers to change their priorities and practices have lagged behind. This is true even in fields where funders require publicly accessible data deposit, in part because of the challenges funders face in enforcing compliance. Absent stronger enforcement or substantive transformation in research cultures, or in all likelihood, sustained investment in both, data sharing may remain spotty. Neither topic is mentioned in the Nelson Memo, so it appears that the policies of individual agencies will be important factors in whether its most transformative possibilities become reality.

Opportunities for Repositories?

Domain and general repositories are an essential and now familiar part of the data sharing infrastructure. However, as our colleagues Roger Schonfeld and Rebecca Springer have pointed out, even the largest generalist repositories have struggled to develop sustainable business models. Specialized domain repositories often rely on grants for start-up funds. Even well-established domain repositories face financial challenges as those funds run dry. Though smaller and thus cheaper to maintain than generalist repositories, they also appeal to a narrower user base and have little to no full-time staff to make needed updates to the platform. The Nelson Memo specifies that federal grantees should be allowed to include costs associated with submitting, curating, managing, and publishing data into their research budgets, so both domain and generalist repositories could see opportunities for revenue growth.

Current policies at major agencies such as NSF and NIH encourage researchers to deposit in domain repositories when available, while leaving the ultimate choice of repository to grantees. While it is possible that some agencies may decide to create their own repositories, the Nelson Memo signals that current approach will likely continue. In theory, this should benefit domain repositories, which may have opportunities to raise revenue for deposit and even develop fee-based services. To maximize the possibilities of the Nelson Memo, domain repositories will need to convince researchers to designate them as the location of deposit in data management plans and grant budgets. Many domain repositories do not currently have well-developed marketing and communications strategies, which could hamper their ability to do the kind of outreach that will be required to maximize these opportunities. Moreover, it does not appear that federal agencies are expected to provide additional funds to costs associated with data sharing: those expenses will likely eat into research awards. Domain repositories will need to assess whether they can price deposit and services competitively, which could be a challenge given the economies of scale that generalist repositories can leverage.

It is quite possible that generalist repositories will emerge as the main beneficiaries of changes to federal policy. Some evidence suggests that researchers tend to prefer institutional and generalist repositories, and depending on how the issue of data that is not associated with publication plays out, a large percentage of the data newly subjected to data sharing requirements could come from fields without existing domain repositories. Both commercial generalist repositories like Mendeley Data or Figshare, and not-for-profit options such as ICPSR, Dryad, or Zenodo have capacity to adopt new features, accept a wide range of data types, and integrate data deposit into publication workflows.

Looking Ahead

The full effects of the Nelson Memo on the data sharing landscape are unclear, but organizations with stakes in the outcome will need to begin making decisions about how to navigate the new policy now.

Domain repositories could see opportunities for new revenue that can sustain their operations, and should invest in marketing and outreach to communicate their value to potential users. These include being the preferred option of funding agencies and the fact that domain repositories are where the researchers who are most likely to be interested in and reuse data are most likely to congregate. However, the challenges domain repositories will likely face in the new environment are considerable. Their success may depend on their ability to make investments in their infrastructure to ingest and manage larger volumes of data. Well-established not-for-profit and commercial repositories will be better able to raise the capital to adapt to new business conditions than most domain repositories could hope to be. Domain repositories should consider doubling down on their unique ability to serve particular data communities. They might, for example, offer metadata that is more attuned to the needs of a specific community of researchers, develop specialized data management services, or emphasize their status as community gathering places by adding chat features, virtual workshops, or networking opportunities. Some might consider shifting their focus away from archival activity and instead focus on enabling easy discovery of data spread across repositories that is of value to their communities.

The largest not-for-profit generalist repositories have built recognizable brands and a level of financial sustainability that can give depositors confidence that their data will not vanish. Many also have earned the trust of researchers, librarians, and others who will have influence over where data is deposited. Moreover, they have resources that most domain repositories lack to develop new services and features that may provide additional revenue.

However, they will need to be careful of being overtaken by commercial repositories owned by publishers. Publisher owned repositories could gain a critical advantage due to new federal policies because data deposit will be required to coincide with the publication of peer-reviewed research. It seems reasonable to believe that many researchers will seek to combine these activities, especially if publishers offer workflow tools to facilitate this kind of dual submission. As Tim Vines has pointed out, publishers may also take on the role of compliance officers in the process. There is an irony here: the Holdren Memo clearly envisioned a significant role for public-private collaboration, language that is absent from the Nelson Memo. Yet, a version of these partnerships may well be the most likely outcome of the new policies.

Discussion

1 Thought on "Guest Post — The Outlook for Data Sharing in Light of the Nelson Memo"

Publishers will also be eying the Nelson Memo as a significant business opportunity. Right now publishers see no economic value in open data because an article with all of its datasets shared nets exactly the same APC or subscription revenue as an article that has shared nothing. (Publishers can derive significant social value from open data, but that’s another story).

That economic value proposition changes if funding agencies turn to publishers to help enforce the Nelson open data mandate, as the funders must then give the publishers sufficient resources to make enforcement happen. In fact, there’s nowhere else the funders can turn because only publishers have consistent access to in-review (and hence editable) articles.

Proactive publishers are therefore likely to a) get a lot better at tracking funding metadata, and b) develop workflows where articles from US funders are checked for data sharing during peer review, and c) establish agreements where the funders pick up the cost of the compliance check process.