There is an elephant in the scholarly infrastructure room and, while some are ready to talk about it generally, few want to describe that elephant in all its glorious detail. That elephant is the guidance organizations provide to the community about the use of persistent identifiers in our community. At present, the guidance is too vague and it needs to be specific, at least at a high level, in order for the national and international mandates to be most effective.

The August 2022 OSTP “Nelson” Memo laid out in general terms what it would take for content to be IDEALLY publicly available. This included when content should be released, and also its form and structure, suggesting that content should be made accessible in a structured form (i.e., XML or similar) along with associated “Digital Persistent Identifiers” (DPIs)—using the OSTP memo’s language, though these are more commonly referred to as persistent identifiers (PIDs)—and metadata. Because the memo is providing guidance for the numerous agencies impacted by the new policy so that they can craft their own plans, it didn’t provide explicit instruction on what those DPIs should be or the exact structure of basic metadata. It is anticipated that the affected agencies will then put forward their own specific plans, due to be submitted by February, for implementing these principles.

Within the sphere of scholarly communications there is a common understanding of the value of PIDs, metadata, and this infrastructure in improving things. There have been studies about their value, even in domains where their application might not be obvious. It is past time that we all agree on a core set of identifiers and basic metadata elements and begin to encourage researchers to use them at scale when communicating their results. In order to facilitate this, funders, publishers, and systems providers need to ensure that ease of use and seamless interoperability are achieved so as not to create barriers to adoption.

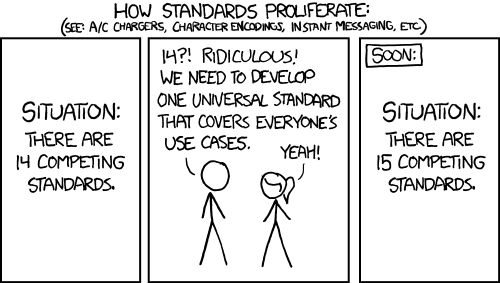

Persistent identifiers should be unique within the context of their domain. This is part of the guidance provided by the ISO Principles of Identification (ISO TS ISO/TS 22943). The introduction to that Technical Specification cautions that, “Any community of practice should carefully consider, and be appropriately cautious in adopting, any proposal that increases the number of identifiers used to deal with similar populations of referents.” This point bears specific focus, lest we get into the very familiar situation captured so well by XKCD (see featured image). Sadly, this has already happened and I fear it will continue to happen if agencies and other funders are not more explicit in their mandates for the use of PIDs in scholarly communication.

It is widely acknowledged that when people in our community say “Digital Persistent Identifier for People”, they are referring to ORCID. When people say “Digital Persistent Identifier for articles” that is generally understood to mean a CrossRef DOI. “Digital Persistent Identifier for institutions” is increasingly understood to be ROR identifiers. “Digital Persistent identifiers for a data set” is ideally linked to a DataCite DOI. For physical samples, that Digital Persistent Identifier is ideally the International Generic Sample Number (IGSN). For basic metadata, the 15 core elements that comprise the Dublin Core (or the ISO version) metadata is generally sufficient as a baseline for almost every research output. This is not an exhaustive list of the PIDs that are consistently applied. Arguably, the more detailed that list gets, the more problematic some communities will find the guidance.

Are there other identifiers that can lay claim to being a digital identifier in each of these domains? Yes, absolutely, there are. For institutions, there are ISNI, GRID, DUNS, Ringgold, Legal Entity Identifier (ISO 17442), VIAF, WorldCat Identities ID, organizationally unique identifier (OUI), or even a WikiData identifier (among many others). Similarly, for people there is a broad list of other identifiers, such as ISNI, VIAF, and WorldCat Identities, Scopus Author IDs, or even U.S. social security numbers and Facebook IDs. Each of these has their unique purpose, market niche, and use case, but certainly with overlaps. EMBL’s European Bioinformatics Institute (EMBL-EBI) runs the identifiers.org service, which provides information on 805 identifiers (as of today) used in scholarly publishing. Many of these identifiers are very specific to their domain, such as PaleoDB, which provides identifiers and taxonomic data for “plants and animals of any geological age”, the Addgene collection for information on plasmids, and Software Heritage, which provides a universal archive of software source code.

Will promoting a select set of universally adopted and recognized identifiers mean these other PIDs don’t have value or meaning? No, absolutely not. Each identification structure and system has its own role in the community, and specialist services are appropriate and needed for some communities. The notion that there is a universal set of identifiers that can apply in most cases need not suggest the idea that this set will work for every situation and every use case. Realistically, this is an example of the Pareto principle at play. For the overwhelming majority of cases, the existing and adopted structures of scholarly exchange will work best. The ambiguity of the edge cases shouldn’t preclude us from stating — ideally, mandating — the obvious for the 80+% of cases where they can readily be applied. In fact, it will be more of a problem if we don’t limit the growth of new PIDs where others already exist, before the list extends even further.

Institutional IDs provide an illustrative example. Back in the early 2000s, Ringgold was formed as a service to unambiguously identify institutional subscribers to scholarly content. The Ringgold ID and their institutional taxonomy was widely used by publishers in order to clean and maintain their subscriber lists. In 2012, when ISO published the International Standard Name Identifier (ISNI), the potential for using this system for institutions was already clear and within scope of the system. Although ISNI had originally been envisioned as an identifier for creators of content, primarily for the use-case of tracking royalties, it became clear that “creator” could encompass any range of parties, including people, pseudonyms, groups of people (bands), or even corporations. The NISO Institutional Identification (I2) recommendation was published in 2013 and, noting the publication of ISNI, recommended its use for this purpose. In 2013, Ringgold was among the first registration agencies for the ISNI system and most of the institutions assigned Ringgold IDs now also have ISNIs, the two are not the same. Meanwhile, Digital Science developed and provided the community a public domain release of its institutional service, GRID. Building upon this, members of the PID community led by California Digital Library, CrossRef, and DataCite came together to launch the Research Organization Registry (ROR), which was initially seeded with the public domain data from GRID. While GRID is no longer publicly available, it has forked from ROR and remains in use within Digital Science systems, and other systems as well. Ideally its use will continue to be deprecated. Some argue that the openness and community governance of ROR justifies the investment in creating and managing the system, which indeed it might.

A number of tools and services now exist to connect this network graph of identifiers and outputs, so that the interconnected world of science can be navigated. As one example of this, specific to organizations, OpenAIRE has developed the OpenOrgs Database, which can be used to “address the disambiguation of organizations.” One would think this would already have been solved by the proliferation of organizational IDs with different applications; instead, this growth seems only to have driven the need for more tools to solve the identification problem. Ideally, settling on a single approach would reduce overall costs and improve interoperability in the ecosystem.

What we may need is a community consensus document funders can reference, so that rather than funding organizations mandating these decisions, which they seem reticent to do, the community reaches agreement that, “what we mean when we say “Digital Persistent ID for ______ is _____”. The funders would then simply be following what most people understand as the most reasonable path forward. Of course, the consensus can, and probably should, include the caveat that there are domains of research activity that need their own special snowflake of an identifier. However, these cases should be limited in both scope and domain application.

Ideally, more organizations — publishers, as well as funders — should not just suggest this as is mostly the case now, but also make these types of identifiers and metadata mandatory, with limited exemptions for the edge cases that do exist. Of course, mandatory doesn’t necessarily mean that every researcher will have to memorize their organization’s ROR ID. Ideally, the systems will be integrated with APIs and lookup tools to manage this ID assignment and verification process with minimal effort by the researcher during the submission or application process. The lack of investment here has hindered wider adoption and application of PIDs. It would be extremely helpful if funders and publishers were to use the influence that they have to bring the community closer to consistent application of these infrastructure elements.

Daniel Sepulveda, Senior Vice President at Platinum Advisors, spoke on the path forward for this agency guidance during the Charleston Conference earlier this month during a panel on the OSTP memo and its implications. After the submission of the plans and their review, the likeliest next stage will turn to the Congressional committees for Commerce in the Senate, and in particular the Senate Subcommittee on Space and Science, and its counterpart in the House of Representatives. These committees will be involved in shaping the policy environment through their oversight and appropriations authority, and will have a significant impact on the eventual activities of the respective agencies. We therefore have a great opportunity to organize the community’s core understanding of these issues, perhaps through a consensus document that can be included in these policies by reference, before the plans get too formulated and then the activities turn to the legislative process. The reason for this is simple. As Daniel said, “To the people in Congress, an orchid is a flower,” and they have no idea what an ORCID is apart from a misspelling of the word for a flower. Our community needs to come together and express in policy guidance exactly what we mean, which is to say a small set of PIDs should be applied and we should name them specifically as “ORCID” (and CrossRef DOI and… and… and…) before someone from these committees and outside of our community insists that we use “DPIs” that they have defined and decided are most appropriate.

This extends well beyond the situation with the OSTP guidance and the plans being developed by U.S. Federal Agencies. This guidance should be the same in the EU and the UK, each with their funding mandates, as well as with guidance issued by cOAlition S and the Open Research Funders Group, and any other funders of research. One can easily envision a scenario where some significantly large domain or country decides that the existing scholarly infrastructure of PIDs and metadata isn’t quite right for them, and they create their own identifier for people or outputs in that domain or region. The unnecessary confusion, programming, and resource deployment necessary to navigate the increasing network of information will be significant. In the end, it won’t help anyone. To slightly misquote the XKCD cartoon, “Soon … There will be 15 competing PIDs.”

Discussion

13 Thoughts on "We All Know What We Mean, Can We Just Put It In The Policy?"

Don’t forget about handles for unique digital object identification…

It is also possible that “we” (whoever that is), who know what we mean, don’t all actually mean the same thing? For example, for all of the messaging from cOAlition S re Plan S uniformity, if you look at the funder policies, they aren’t uniform at all.

There is something decidedly off about an organization (the U.S. federal government) which has, for example, more than a dozen agencies meddling in housing finance policy, all with their own agendas and sets of acronyms, dictating to the research community a need to standardize identifiers. And given their success rate, or lack thereof, in making their purpose and intent clear from year to year, the author’s point about the need to get out in front of those people could not be more on target.

It’s good to see this push for what in the end is the only rational approach. I also find it helpful to see the specific recommendations from Todd, especially that ROR and IGSN are the ones to go for when identifying institutions and physical objects.

Just one quibble:

“For basic metadata, the 15 core elements that comprise the Dublin Core (or the ISO version) metadata is generally sufficient as a baseline for almost every research output.”

I have always found Dublin Core grotesquely inadequate. For example, when encoding the metadata of a perfectly simple article reference like “Taylor, Michael P. and Darren Naish. 2007. An unusual new neosauropod dinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous Hastings Beds Group of East Sussex, England. Palaeontology 50 (6): 1547-1564. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2007.00728.x”, there is no way in the standard 15 elements to represent journal-title, volume, issue, start-page, end-page or DOI. All the information, in fact, that you need to actually find the article.

a couple of comments from the research analyst\administrator\applied scientometrician perspective:

Outputs: Crossref DOIs rule, Datacite DOIs are widely used. They use two different databases for the metadata they harvest, so that Crossref API lacks Datacite dois and vice versa. This is not quite good because Crossref API\dumps form the backbone of the “new open” bibliographic\bibliometric services like OpenAlex. Thus in terms of maximising discoverability and connectedness datacite DOIs lag a bit.

Also a HUGE problem with the CS crowd who often don’t give a damn about DOIs. JMLR (a top ML journal)? No DOIs! NeurIPS (a top conference)? No DOIs!

As AI\ML is arguably the most important discipline in the whole STEM right now, this is the real elephant in the room, seemingly invisible to Scholarly Kitchen and its traditionalist chefs serving the big old journal publishers.

Authors: ORCID is here, but rates of adoption are still inadequate, and metadata quality is often poor. This is mostly because authors still don’t see any meaningful benefits, and many publishers still not making ORCID mandatory for submissions (why?).

Orgs: ROR is the clear leader, but data quality and curation is often poor, especially for non-OECD countries. ROR adoption in Crossref metadata is very low, but this could be alleviated via org disambiguation and paper metadata enrichment in OpenAlex and other tools. The one bottleneck with ROR seems to be the case when the authors can’t find their org in the ROR-connected autocomplete form for entering affiliations at the publisher’s website (if there is any such form at all). They can’t add the missing org immediately, so end up with no RORs in their papers.

Concepts\Topics: This is important and will become more important with the advent of semantic web. Wikidata is the prime contender.

Funding Sources: This is very important for those who push to open by bundling openness and funding. Funder Registry is ok, but adding new funders is obscure and not transparent. Currently it is just a general contact form at the Crossref website without any description of the process and data curation. Also of note for funders and governments is the lack of a PID system for research infrastructure.

Journals and other venues: ISSNs are still a mess, and “canonical” ISSN-L implementation is not widely adopted. And still no PIDs for conferences.

So, a long way to go, as always 🙂

viam supervadet vadens

Orcid mostly makes sense for anyone who has a PhD and/or intends to keep publishing after their PhD. However, if you’re an undergrad who is lucky enough to get on a paper or someone who has other professional aspirations, the need for a unique 12 digit identifier to link you to your 3 articles is a hard sell.

Agree with your points, Ivan – it all needs much more adoption. Come on ML-ers!! Put us in touch and I will give them the pitch 🙂 Incidentally I believe NeurIPS previously used DOIs but then abandoned them 🙁

And you’re right that the Crossref Open Funder Registry process isn’t clear at the point of requesting additions or changes. There is a description elsewhere on the website, but in short, these requests go into our support ticketing system, which is private (for now) and takes a few weeks to process, which involves some back-and-forth with Elsevier, who originally donated the seed registry and continue to curate this pro bono for the community (a little known fact!). We’re definitely planning to make this process completely transparent, and the ROR curation strategy shows a model that really works (whilst still ramping up, any changes can be seen on a public status board, and there are very frequent releases, sometimes four times a month).

Thanks for this post! It seems to me however that it is important to maintain a certain diversity within PIDs, notably because they are managed by specific and focused communities, and associated with specific metadata with their own management method. Let’s take the example of ORCID and ISNI. These two identifiers are closely linked since they have the same syntax and ISNI International Agency reserves a portion of its ISO-endorsed identifiers for the exclusive use of ORCID. It is therefore important that these two organizations work together to establish bridges between their PIDs, which are both widely used, so that the metadata qualifying a researcher in each database can be cross-referenced, and mutually enriched. This is true for other PIDs, and the ISSN Portal (https://portal.issn.org) relies on data from several partners to cross-reference ISSN-identified journal titles as well as other continuing resources.

Interestingly, in Plan S, the initial explicit requirement:

“Use of DOIs as permanent identifiers (PIDs with versioning, for example in case of revisions)”*

has been modified to allow for more options, following public consultation:

“Use of persistent identifiers (PIDs) for scholarly publications (with versioning, for example, in case of revisions), such as DOI (preferable), URN, or Handle”

I do like the approach to give concrete examples and express a clear preference, while also leaving space for different approaches and use cases. Which, incidentally, I would not label ‘snowflakes’…

(I also think in this regard there is a difference between DOIs (which carry direct costs for assignment) and ROR and ORCID, which do not and have challenges more around community uptake and financial support on a different level).

*see https://web.archive.org/web/20181231095105/http://www.coalition-s.org/feedback/ for archived version

Thanks for the article, one minor issue. Why use only IGSNs as identifiers for physical objects? Sure rocks are cool, but we don’t generally use them in biomedicine. Physical things also include biological entities such as mice and antibodies (and plasmids thanks for at least mentioning those). We have RRIDs to cover those, most recently we got to 500,000 of them in the scientific literature (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35701373/)!!!

Not all article/book/conference/preprint, etc. DOI’s are Crossref DOI’s. There are multiple registration agencies around the world. There are a number of journals in Europe that register their articles with registration agencies other than Crossref. And most articles published in Japan in Japanese, and in China in Chinese are registered with national registration agencies, not Crossref.

While the majority of article content is in Crossref, having content registered with other registration agencies makes reference linking (Crossref’s original mission) across all content more challenging, and it also presents challenges for metadata usage when it is necessary to acquire metadata from multiple agencies each of which has its own data schema.

Crossref published some practical guidance last week (also reviewed by ORCID and DataCite): https://www.crossref.org/blog/how-funding-agencies-can-meet-ostp-and-open-science-guidance-using-existing-open-infrastructure. The infrastructure exists; it just needs more adoption, and it seems like the US agencies will pick up the pace now.

How can we help here?