Editor’s Note: Today’s post is by Alicia J. Kowaltowski, José R. F. Arruda, Paulo A. Nussenzveig, and Ariel M. Silber. Alicia is a Full Professor of Biochemistry at the University of São Paulo. José is Full Professor of Mechanical Engineering at the University of Campinas. Paulo is Professor of Physics and Provost for Research and Innovation at the University of São Paulo. Ariel is a Professor at the Institute of Biomedical Sciences at the University of São Paulo.

Many scientists worldwide have embraced the idea that research publications should be openly accessible to read, without paywalls. Rightfully so, as academic research is mostly supported by public funds, and contributes toward societal progress. Indeed, the quest for open publications has led to many groundbreaking initiatives, including the creation of new author-pays open access (OA) journals and publishers, the expansion of public preprint and postprint repositories, and the establishment of Sci-Hub, a radical open repository of scientific publications, often obtained illegally. But subscription publications persist, as well as resistance toward depositing preprints, leading to more recent initiatives to accelerate the universal transition to OA in scientific publications. Notably, a recent mandate established that US federal agencies must create policies to ensure all peer-reviewed publications are made publicly accessible by the end of 2025. This follows Plan S, launched in 2018 by a consortium of mostly European research funding and performing organizations, which requires that all publications from 2021 on must be OA. An additional mandate within Plan S is that hybrid models of publishing, in which authors can pay to publish OA papers in journals that also publish under subscription models, are acceptable only under certain circumstances, and only until December 31st, 2024. This means that major subscription journals wishing to publish work by authors with Plan S funding will need to transition to OA-only by 2025.

Plan S covers peer-reviewed publications, so depositing a preprint in a public and open archive platform (green OA through preprints) is not sufficient for compliance, although the practice is encouraged. Publishing in a subscription journal and making the accepted version of the manuscript immediately openly available in a public repository (green OA through postprints) is compliant with Plan S, but undesirable for many publishers. Although there have been concerted actions promoting the creation of alternative publishing models that are both open to read and free to publish (known as diamond or platinum OA), these are still rare or poorly publicized in most scientific areas. Diamond OA journals are often the result of personal efforts within small groups of scientists and will need time to reach adequate funding models, quality, visibility, reputation, and indexing, while repositories created by large organizations, such as Open Research Europe (European Commission), have limited visibility in the scientific community. As a result, authors of scientific papers who wish to equitably showcase their research may have limited choices outside of article processing charge (APC)-based journals as soon as 2025. In this scenario, the cost to publish OA is quickly becoming a new paywall in science, substituting the difficulty to read papers with the inability to showcase results in journals seen as reputable, due to the financial barrier of APCs.

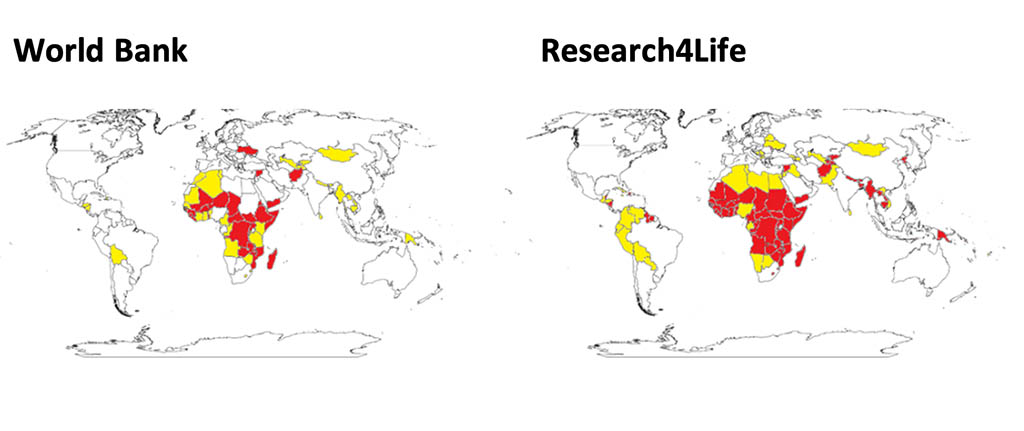

Perhaps recognizing that publication costs could be a barrier toward inclusive publishing, Plan S includes a provision that the journal/platform must provide APC waivers for authors from low-income economies and discounts for authors from lower middle-income economies. This policy is based on World Bank classifications of national economies and is adopted by companies such as Springer Nature (including Nature Portfolio and BMC journals) and Taylor & Francis. It sounds good in principle, but in practice is very limited: the leftmost map below shows countries eligible for full APC waivers according to this economic definition in red, while those qualifying for discounts (typically 50%) are shown in yellow. It is easy to see that many (if not most) countries widely recognized as developing, in which research investments are significantly lower than in the US or most of Europe, are not included by this waiver and discount recommendation. Indeed, no Latin American country qualifies for full APC waivers, since all are technically at least lower middle-income economies; only a handful qualify for partial discounts.

Other publishers, including Wiley, PLOS, Elsevier, SAGE, and AAAS follow the recommendations of Research4Life, a partnership to provide free or low-cost publication in their OA titles. The map on the right below shows waiver (red) and discount (yellow) coverage within this program. While it is significantly more comprehensive than World Bank definitions, it still does not include large countries with known economic constraints for research funding such as Argentina, Brazil, India, Mexico, and South Africa.

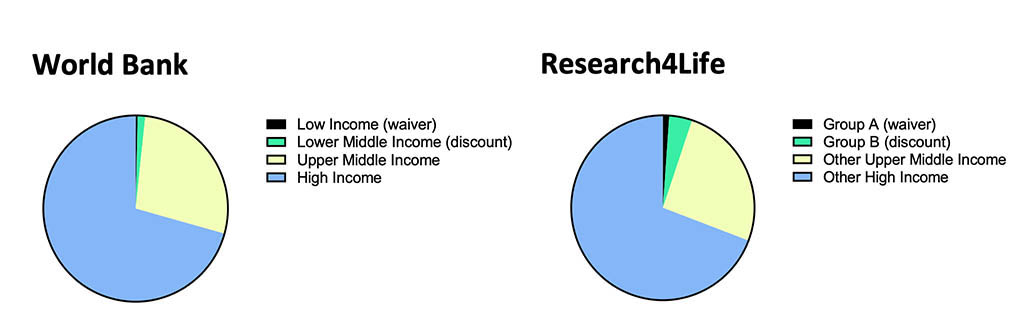

We were curious to see the impact of waiver and discount policies, so we probed the Scopus database for the number of papers published over the last 10 years with authors from each country/territory of origin listed by the World Bank. We found that authors who qualify for APC waivers correspond to a minute percentage of total publication origins: only 0.35% of publication origins are low-income economies, thus qualifying for full waivers in journals that adopt World Bank classifications. Lower middle-income economies, qualifying for discounts, correspond to 1.32%. When using Research4Life classifications, 1.12% of origins were from Group A, which qualifies for full waivers, and 4.05% from Group B, which receives 50% discounts. This demonstrates that even the more comprehensive current waiver and discount policy covers only a minute proportion of papers indexed in this database.

We also wondered if economic status and qualifying for waivers affected the tendency to publish OA. The Scopus database identifies OA publications both when they involve full access to the text at the journal site (gold, hybrid, or bronze OA) and when the full text is available as a preprint or postprint in an open repository (green OA) identified by Unpaywall, an organization that locates legal full-text versions of papers. We quantified OA publications according to the Research4Life country groups, and found that, while nations receiving full APC waivers contribute toward a very small percentage of total publications, a large fraction of these are OA: 52%, including papers that are open to read at journal websites (45%) and in repositories (40%). This may be facilitated by APC waivers offered by most publishers to authors from these nations. Indeed, the percentage of OA publications was lowest in middle-income economies which are excluded from Research4Life´s waiver and discount groups: 32% in total, with 27% available at journal websites and 31% in repositories. These middle-income countries typically have much smaller research budgets than high-income economies, yet are expected to pay full APCs, which may lead to an avoidance of OA publishing. While high-income economies publish more often in OA journals relative to middle-income nations, 45% of publications in total (31% at journal websites and 36% in repositories), the proportion is lower than waiver-qualifying Research4Life Group A nations. Overall, this suggests authors from middle-income countries which aren´t included in Research4Life already publish less in OA journals, suggesting they may be economically excluded from this option currently, prior to the projected full transition to an OA-only publication landscape in 2025.

Admittedly, most publishers also consider individual requests for discounts or waivers, in addition to those qualifying due to their national origin. Indeed, some publishers (such as Frontiers and MDPI) only consider individual waiver and discount requests. However, personal requests for individual waivers present several disadvantages, including reduced bargaining power, as they involve personal endeavors. Individual requests may also be burdensome, and are often denied, habitually citing World Bank or Research4Life classifications as qualifying criteria. Furthermore, collective agreements with publishers to cover APCs at an institutional level, which have become common in the Global North, are rare in developing nations, in which funding and research institutions are smaller, less politically stable, and less prepared to negotiate with highly profitable publishers.

Open access is not only desirable, but necessary to ensure that the full benefits of research can translate into societal gains. Indeed, equal access to scientific output is recognized by UNESCO as essential for human development and critical for achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals. With this in mind, the transition to open access should involve special care to avoid exclusion of authors owing to the financial burden of APCs. Considering the very limited extent of current waiver and discount policies, we believe that expanding full waiver policies to include all low and lower middle-income countries, as well as applying 50% discounts to all upper middle-income economies, would be a much more reasonable waiver and discount policy, and better reflect the enormous differences in global wealth. In practice, this would involve giving full waivers to approximately 2% of authors and discounts to approximately 25%, which could easily be absorbed by most publishers, as this sector is known for its unusually high profit margins. Adopting a more inclusive waiver and discount policy would ensure that the transition to a fully OA publishing model has a better chance of providing all authors, including those from middle-income economies, the ability not only to read papers, but also equitably publish their research findings.

Discussion

23 Thoughts on "Guest Post — Article Processing Charges are a Heavy Burden for Middle-Income Countries"

we believe that expanding full waiver policies to include all low and lower middle-income countries, as well as applying 50% discounts to all upper middle-income economies, would be a much more reasonable waiver and discount policy, and better reflect the enormous differences in global wealth. In practice, this would involve giving full waivers to approximately 2% of authors and discounts to approximately 25%, which could easily be absorbed by most publishers, as this sector is known for its unusually high profit margins.

While I don’t disagree that an APC model is problematic in terms of disenfranchising authors from lower and middle-income countries, I do feel that the authors engaged in an ecological fallacy to support their position. Ecological fallacies take place when an argument is made to support individual instances from general conclusions. In this case, from the percentages of worldwide authorship participation to economic models that determine individual publisher and journal budgets.

Take for example, Journal A, an international multidisciplinary journal in the sciences may publish just one paper per year that was by researchers in a low-income country. Offering these authors a waiver may not have any significant effect on their operating budget. The publisher could adhere to the new policy, at least for this one journal.

Journal B, however, is a regional journal from a low-income country that publishes in its national language. In this case, nearly 100% of its authors may be eligible for a subsidy under an APC model. This publisher could not adhere to the new policy for its journal and, likely, for other journals from its portfolio.

The net effect of such an expanded subsidy policy, writ large, would result in the financial insolvency of many local and regional journals and their publishers. Most scientists would consider this outcome an undesirable and unintended consequence. Those who are quick to blame commercial publishers for their monopoly-like grip on the market and their “unusually high profit margins” may be surprised to find that their policy, if adopted, would only lead to strengthening commercial publishing. Is this what our guest authors truly support?

Phil, it seems like your argument might be a bit of a red herring. When researchers in the Global South express their concerns about rising APC costs, they are not—from my reading anyway—generally talking about preprints, predatory journals, and regional journals, together which wield limited influence and are comparatively affordable. Rather, their concerns revolve around speciality journals (which account for about 75% of all journal articles) and, of course, prestige journals. I have read as many articles and surveys as I can find on this topic and there is profound concern on this issue. Statistical arguments aside, I think you would be hard pressed to find any group of authors anywhere in the Global South who think the current APC solutions are acceptable. Simard’s recent work (doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0272730) also talks about how even though APC waivers are “avaiable,” they not widely used (because of what the authors mention here, or other factors, such as all authors needing to come from the eligible country).

One might argue that this post makes a more eloquent argument for finding non-APC models for journals, rather than an argument that the APC model can be fixed by increasing the amounts of waivers granted.

To expand upon Phil’s point, it’s one thing to suggest a commercial publisher with a large profit margin voluntarily take a slightly smaller profit in order to drive equity, it’s quite another to ask a small, non-profit, independent publisher to make those same reductions, as the impact on sustainability will be much greater. This solution, again, drives authors to the publications of the larger commercial publishers who can afford waivers, further cementing their power in the market.

But David, who is asking the small non-profit publisher to do this? The vast majority of the concerns around APCs are centered around the costs of publishing in the journals that researchers rely on—-not just from the Big 5 publishers (although that gets you to what—50% of the total?) but also the specialty journals that account for most of what’s read and has an impact. If the small, regional, Journal of Southern Florida Swamp Things (JSFST) is only charging $500 per article and can’t afford to offer widespread discounts, no one is really complaining because no one reads JSFST, and also because $500 isn’t the same devestating budget hit as publishing in a marquee journal. If you have data on this point you and Phil are making, please do share—it’s an interesting point but one that hasn’t really been raised much to-date. The argument is more one of widening the gap between the already priveleged researchers who can already afford to publish in the best journals, and researchers from lower resourced regions of the world who will NEVER be able to publish in these best journals given our current solution frameworks. It isn’t an argument of who will be able to continue publishing in JSFST.

Hi Glen,

I take exception to your idea that anything not published by a large, commercial publisher is on the level of the Journal of Southern Florida Swamp Things and only has an APC of $500. There are tons of good high-end and middle of the pack field-specific journals run independently be research societies and organizations out there. But when small society journal X charges a $3000 APC, their costs are generally much higher than the equivalent journal at Big Publisher Y (which sees lower costs due to scale), which also has a $3000 APC and a higher margin. If you ask both to offer the same number of waivers and discounts, the Big Publisher journal may continue to be profitable (due to its lower costs) while the small journal may go under. That was the only point I was trying to make — if you assume all journals are published by big commercial publishers and you base your rules around that notion, you may be reinforcing the dominance of those journals at the expense of other approaches.

In the end, the right solution should be journal/publisher agnostic. Researchers want to publish their papers in the best journal they can get into, the one that reaches the right audience for their work. If you limit waivers and discounts to only the commercial journals, then the authors are shut out of the JSFST’s of the world. Which is not equitable and thus not a solution to the problem here.

Speaking as an author and editor for just the specialist, society-driven journals you mention, you are exactly on the button. Some are in the hybrid stage, some are doing rather desperate accounting, some are watching the impact of Plan S very nervously. Someone should take a look at the research done without any significant funding from institutions, grant-givers and national governments. By signing up to Scholarly Kitchen, many tears ago, I have been the conduit for passing on the “news” to some journals. So far, the messenger has not been shot.

Hi Glenn. I’m simply pointing out the logical flaw in the authors’ piece and arguing their solution (more APC discounts) will lead to undesirable consequences. We’ve been following the OA debates for two decades, and honestly, it gets pretty tiresome. If we’ve learned anything, it is that the APC model isn’t as messianic as first proposed; and secondly, that big changes in policy can often lead to undesirable consequences. If someone proposes an alternative, it doesn’t have to be a perfect solution, but it does need to be demonstratively better than what we already have. This post doesn’t rise to that level.

I totally agree with both of your points here Phil—that APC’s (as we currently know them) aren’t the be all end all solution for everyone everywhere, and that tinkering with policies is going to lead to unexpected (and often undesirable) consequences. I do seem to have a beef with dismissing the idea of increasing discounts, though (through whatever means—higher discount percentages, expansion, better awareness, etc.) because of the imagined impact on regional publishers. I’d sure like to see this modeled before we consider it a real risk. I’m not saying it isn’t and don’t mean to dismiss this impact out of hand because it may indeed be real and significant. But channeling the authors’ concerns here (and the concerns of other authors who have described this situation), they aren’t concerned about their capacity to publish in regionals. This isn’t where the gap exists and is growing. It’s in their capacity to publish in the journals of the most consequence, which are more expensive and getting more so. Policy is always a matter of tinkering to find the best outcome, right? And in this case, since we’re clearly barreling down the APC policy path (which is quite likely NOT the best outcome for MOST of the world’s researchers), then it’s incumbent on policy makers to try to avoid a total train wreck here. Making sure our discounts work may be step one. Being prepared, as the authors suggest, to expand these discounts as needed may be step two. But we need to model, of course, what the pros and cons of this proposal look like beforehand. My GUESS is that the pros will outweigh the cons—that the small regional journals are already priced affordably enough that they won’t be put out of business by discounts (i.e., a 50% discount on a $5,000 APC will still be way more than the $500 full sticker price for a regional APC). Maybe what I’m suggesting here, then, is that the discounts the authors are suggesting would ONLY apply in cases where the APC is higher than a certain figure (with some math thrown in to make sure that we don’t get weird outcomes at the margins).

Thank you for your comment. In the Global South, we are very familiar with local journals. All those I know in Brazil are either diamond open, funded by scientific societies and/or public money, or practice very low APC values, usually below US$500 and in local currency. They are not the issue here. Some societies, such as the one I am a member of (Brazilian Society of Mechanical Sciences and Engineering), have made agreements with commercial publishers (Springer in this case) and became subscription journals, in which case authors from Brazil usually cannot pay for open access. We understand the importance of publicly funded diamond open access, and Brazilian SciELO is a good example of this (FAPESP commits nearly one and a half million US dollars yearly to this initiative), but we urge commercial publishers to implement more effective waiver policies. This is vital to allow researchers from upper-middle-income countries to continue to publish in prestigious, highly visible scientific journals as they transform to APC-based open-access models.

Open Research Europe is not a repository, but an open access publishing platform for the publication of research stemming from Horizon 2020, Horizon Europe and/or Euratom funding across all subject areas.

The European Commission expects funders and institutions to recognize the platform as a comparable publication venue to traditional journals.

Here for more information: https://open-research-europe.ec.europa.eu/about/

A very minor point from an author in developed country (UK). Some of us continue to work and publish after retirement, and cannot access institutional funds (the very rare amateur with a significant contribution also fits here). Full APCs falling on a retirement pension are a severe limitation, even if the cases where this happens are few.

Our efforts cost nothing to the public purse.

Thank you for your comment, but consider the difference between the pension of a retired researcher from a high-income country and the one of a researcher from a higher middle-income country. In terms of hard currency, the difference is likely to be significant. Therefore, indeed, there should be a waiver policy for retired, non-funded researchers, but again the country income differences should be taken into account.

Yes of course. I know that I am personally well-off compared to most, employed or not, in less wealthy countries. Nevertheless, a $1000 to $3000 APC would be a big ask, and many would not be able or willing to pay it, the more so since personal income and savings are a family matter in most cases. I have written 2-4 papers a year in retirement, OK, often with employed colleagues; significant four-figure sums on an annual basis are out of reach.

OA publishing trades one form of inequality (can’t afford to subscribe to the journal) for another (can’t afford to publish in the journal). How is this better? It continues to amaze me that so much discussion on this topic never takes into account the staff who work on the journal. While the corporate publishers are in the cross hairs for their profits the blow will fall on the staff laid off and the services cut down or eliminated that authors, reviewers and editors have come to rely on all these years. Many journals will fold due to insolvency and those left will play the volume game – publishing as much as they can to collect the revenue and literally keep the lights on. The consequences will have a tremendous ripple effect throughout the entire scientific community. But the entire focus seems to be how to make the APCs more affordable. And I agree with Phil – if you play the volume game who wins – the large corporate publishers who can use their economies of scale to an even stronger advantage. I don’t actually have a problem with that but I think the proponents of OA do.

It’s not “OA publishing” that does this, but rather the APC funding model. There are other funding models as well — each with its own configuration of costs and benefits, of course.

Fair enough but any way you slice it there will be less revenue generated, the contracts will shrink, staff will be laid off, services will suffer. One can see a waiver as great, a person and their work gets published who might otherwise not get published but one can also see it as great, how am I going to pay for my editorial assistant if I keep giving out waivers and there is almost no other source of revenue for the journal? One year of waivers and discounts might be enough to push a journal to the budgetary edge. Even without those the revenue drop (pubbing the same number of papers) is steep and that has enormous consequences.

Great, four non-experts giving an incredibly narrow perspective of worldwide publishing. There are so many holes in this piece, where to start? There’s no doubting the academic credentials of the authors but this reads as if I, a mere bookseller, were asked to opine on mitochondrial calcium transport or reactive oxygen species. By only considering the commercial publishing industry and the data created by that machine does a huge disservice to the huge number of researchers outside this commercial ecosystem as little more than “the result of personal efforts within small groups of scientists.” The research and data used in this article is so narrow, it is one small part of the world’s publishing universe from which they have extrapolated large conclusions. As such the authors seem to dismiss a much larger body of work and data from which to research and study. As if, in a biochemistry article, they would choose to conduct only research on men as we have more data on them than women. Ignoring, dismissing, and waiving the credibility of any other model than APCs seems to be asking to further enthrench that inequality. Whether that’s for the global south, ECRs, or retired researchers like Robert Cameron above. By knowingly and purposefully selecting such a narrow selection of data the very findings of this piece need real consideration.

I tend to find situations like this to be humbling, rather than reasons to criticize the knowledge base of others. For those of us who swim in the waters of scholarly communications every day, many of these things seem self-evident. But for the researcher, their focus is on their research, not on the world of publishing — in many ways, the publication process is a distraction that takes them away from the work they’re passionate about, so how much effort should they be putting into learning about that distraction? To me it shows how often we assume everyone is as interested in us as we are, and it reminds me of how much navel-gazing our community does. And how much better of a job we could be doing to educate the research community about the reality of the publication process…

Agree with everything you have said here. I recall once at an ISMTE conference in maybe 2018 asking a panel of researchers if they had ever thought of the math (see my other comment) of running a journal and what would a transformation to OA look like and do you know how much a journal makes and how many people it employs etc. and he had no idea. This is not to belittle him at all. That is not his job to know. But he appreciated hearing it, it really made him think. We need more of that. Quick math – journal X grosses 2 million per year on subscriptions, advertising, etc. It pubs 300 papers per year. Now Journal X is OA and charges APCs of $3000. Everyone pays (a miracle) and that generates $900,000. You just lost 1.1 million. How does this work? People are not just debating what is best for the scientific community, they are wondering how are they going to pay their rent when this happens to their journal.

Hi Bob. The authors aren’t going to rush to their own defense but I will gladly. To be clear, there are no PhDs in open access. Everyone studies this issue from their own silo. Most of the world’s OA experts are in fact experts in somethink else—librarians, or funders, or researchers of some sort. I’ve personally read the work of most of the authors of this post, and know that several have been very active in OA conversations for years now and are very knowledgable. So there’s that. Don’t look at Jon Tennant’s resume and think “why was a paleontologist dabbling in OA?,” or think that Rick Anderson and Lisa Hinchliffe are “just” library leaders who should spend their time cataloguing book collections. The other part of this equation is APCs. No one outside of the Plan S fan club is out there with pom poms cheering on the bulldozer that is APC reform—no one. Unfortunately, this reform is moving along pretty much unabated thanks both to Plan S and to major policies around the world that are aligning themselves with this approach. The authors are not endorsing this approach, but are noting that SINCE it’s happening, we need to figure out what to do next. There may indeed be much better options out there like national subscription plans (India) or plans like subscribe to open, or even regional APC plans instead of global—time will tell. But for now, the reality is APCs and what we’re going to do to keep the damage to a minimum. It may all work out just fine—who knows (and maybe effective discounts will be a key part of the solution)—but based on what we’re hearing from many authors around the world, there’s a LOT of concern at the moment.

Wow – days like these make me feel a little embarrassed to be part of this community. Here with have four authors – maybe not publishing experts but one who are grappling with the multiple challenges of being forced to operate in a system developed by and for the global north. Instead of hearing and trying to engage with the very real problem they identify, most commenters instead want to pick holes in the construction of their case rather than engage with the issue.

Personally, I fully agree that APCs aren’t the answer. But the transition away from APCs isn’t going to happen overnight and so imperfect as they are, we’re stuck with waivers and discounts in the short term (as well as building local solutions, where Latin America has been hugely successful). That’s surely an issue that demands our attention.

Amen. Along these lines. Alison, David Crotty was on to something but the comment nesting maximum was reached. David, you said: “…when small society journal X charges a $3000 APC, their costs are generally much higher than the equivalent journal at Big Publisher Y…. If you ask both to offer the same number of waivers and discounts, the Big Publisher journal may continue to be profitable (due to its lower costs) while the small journal may go under…. In the end, the right solution should be journal/publisher agnostic.”

I think you’re at the front end of a policy conversation that needs to be had. For example, what our our goals here? Afforability, sure, but maybe ecosystem diversity and health as well? Let’s say we’re going to use waivers and discounts because they’re the devil we know. For the sake of argument, why would it be wrong to ONLY use these tools on journals from the major commercial publishers? We know that APC prices are driven by market power (much more than reputation)—that the big publishers can charge more because they control more of the market in a particular field. And we know that governments routinely (through small business assistance programs, preferential award programs, etc.) work to improve the diversity in a marketplace by putting their thumb on the scale of competitiveness. So what about some sort of policy regime where the majors get knocked down a peg so they’re priced more affordably, but this price discount doesn’t affect the small players whose survival we (presumably) want to nurture and protect? I’m sure this approach is wrought with legal questions, but fairness to all publishers seem to be at the heart of your concern, so I’m just fishing for an idea that is both advantageous to researchers and fair to ALL publishers. If not differential pricing then maybe by some other arrangment that isn’t collusion but features some kind of internal understanding about who is supporting what needs in the marketplace?—i.e., the same way that Boeing wouldn’t directly manufacture widgets because it’s important to have that widget manufacturer around for engineering support. This is all kind of nebulous—sorry. I’m not sure there’s a concrete idea here yet but to my knowledge anyway this topic hasn’t been seriously discussed yet at the policy making level, and this would be a fine group to think through what might actually work to address all concerns involved. Off-list is fine by me as well if you think this is too much of a tangent for TSK.

Thank you very much for your comment. Indeed, the focus of the article is on how to limit the damage caused by the current transition to OA. Better financing models are certainly welcome. A waver policy is not about the total income of the publisher, but about distributing the financial effort equitably. Paying a US$500 APC in Brazil may represent the same amount of funding effort as paying US$2500 in the US or Germany. For example, a Ph.D. scholarship in Brazil today ranges from approximately US$500 to US$800.