Editor’s Note: Today’s post is by Mariëlle Prevoo, open knowledge librarian Maastricht University Library, Ron Aardening, scholarly communication officer Maastricht University Library, and Ingrid Wijk, director Maastricht University Library.

Imagine a university invoicing all graduating students for both the costs of their study program and the tuition fees of their peers who dropped out along the way. While this situation would strike most as unfair, something analogous happens in the world of scholarly publishing through the charging of open access fees. In this post we will explore how restructuring APC (Article Processing Charge) pricing can lead to fairer cost allocation in scholarly communication.

Open Access publishing is here to stay

Under open access (OA), the public has immediate access to scholarly output free of charge. In the case of author-pays Gold OA, scholars are charged for publishing the results of their research, turning around the traditional library subscription business model by 180 degrees, from a consumer-paid to a supplier-paid model. Funding agencies, governments, universities, and the publishing industry are exploring ways to change scholarly publishing to OA; for example, the Dutch government and association of universities (VSNU) have set a target of 100% OA in 2020.

From subscription to Article Processing Charge

The term processing charge is somewhat misleading, as authors who submit a paper that gets rejected in whatever phase of the process do not have to pay. In other words, rejected articles do not contribute to covering their processing costs.

What is processing in this context? The publishing process can be broken down into three stages a paper can go through:

- it starts with the submission and desk review;

- (in case of a positive outcome) peer reviews; and

- (if peer review was also successful, potentially after revision) further editing and publication.

Each of the stages involves costs for the publisher, for staff salary and overheads, as well as many of the technologies and systems employed. In addition to the processing costs involved in each of the phases, there are other costs involved for the publisher (see for example “Open Access: The true cost of science publishing” by Richard van Noorden). These costs, of course, need to be covered as well, but for reasons of clarity and simplicity, we do not specify them here.

Many discussions have already taken place about how APCs might lead to increased pressure on editors to accept lower quality articles to improve profits. We want to propose an alternative to the current application of APCs that benefits everyone in the scholarly publishing chain.

A high proportion of drafted articles are never published and will drop out somewhere in the publishing process (e.g., only 39% of observational studies with safety outcome(s) registered on ClinicalTrials.gov were published at least 30 months after the study completion). Research by Michael Kovanis (2015) and colleagues indicated that 15% of publications result from the first submission, 47% from the second submission and 20% from the third submission. Many authors are using (or should we say abusing?) the peer review system over and over again without paying for any of the associated costs. For now, most of these costs are paid by subscribers, but in an OA world, the costs would be covered by authors who do successfully publish in a given journal. This arrangement penalizes authors who careful choose where to submit their work while benefitting those who employ a more scattershot approach. Some authors even use journal peer review in place of soliciting feedback from colleagues or carefully crafting the article prior to submission.

In the current APC model, the fee is only charged for published articles. The costs (and profits) of the publisher are therefore covered only by the publishing researchers, with high APCs as a result, particularly in selective journals. If we look at the value of the work done by the publisher in each phase of the publishing process, the publishing costs can be distributed more fairly. And, just as important, a researcher will think twice before submitting a paper to a ‘long shot’ journal.

A better APC model

The idea to split the APC into a submission and a publication fee has been introduced before, e.g. by the Wellcome Trust in 2004, by Mark Ware Consulting in 2009, and in posts in The Scholarly Kitchen by David Crotty in 2016 and Tim Vines in 2018. These publications also address the unfairness of charging authors of published articles for the costs generated by rejected articles. Here, we propose further disentangling these costs: a peer-review fee.

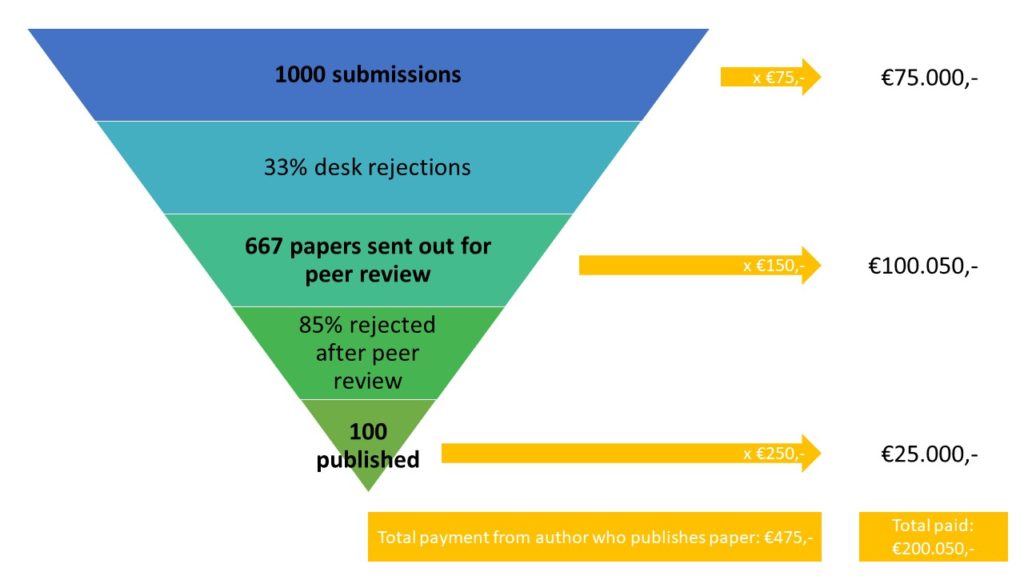

An example: Assume a journal that journal publishes 100 articles, and the current APC needed to cover costs and allow the journal to run a surplus for development and unexpected circumstances is €2,000 (total revenue of €200,000). Let’s further assume that the desk rejection is 1/3 and the acceptance rate (after initial desk review) is 15% (i.e., the overall acceptance rate is 67%*15%=10%). Based on these assumptions, adjusted calculations can be made for a fair division of costs over the separate steps in the process. For instance, having published 100 articles, a total of 1000 papers have been submitted. To earn the same level of revenue, the publisher can charge a submission fee of €75; €150 for reviewing and another €250 for actual publication. In this situation, the researcher needs to pay in total €475 if the article is published (see Figure), a fraction of the €2000 APC under the current model. Transaction costs on the side of the publishers will increase under this new model, because more invoices need to be sent out and handled. However, even if those costs are charged to authors as well, the total costs for one published article will still be significantly lower than in the current situation. Moreover, this adapted APC model can help to avoid free-riding and aiming unrealistically high as a researcher when choosing a journal.

We know from our personal experiences as librarians that scholars only look for a budget to cover the APC once their manuscript has been accepted for publication. For high APCs, they can often feel somewhat reluctant to ask their supervisor, principal investigator or the library how the costs can be covered. In the APC model that we propose, these scholars would have to ask for a budget at the beginning of the submission phase. Having this discussion early on in the publication process takes some of the pressure off, because the amount of money that the scholar is asking for is much lower. Moreover, it can be seen as expectation management, because the party providing the budget knows that more costs are to be expected if and when the manuscript gets accepted.

Journals that have experimented with submission fees before found that submission numbers went down significantly (33.5% in the case studied here) when introducing a submission fee. A decreased number of submissions offers the benefit of decreased costs – less time and effort spent on review as well as lower usage of the often costly technologies involved. Prices charged for various fees would need to be reduced to reflect these reduced costs.

It is not clear whether such a decrease would happen in a situation where the submission fee is introduced by an OA journal that is currently using a traditional OA payment system with an APC charge. In that situation the introduction of the submission fee would lead to a substantial reduction in charges paid for a published article, which may attract more authors, offsetting any decrease caused by the submission fee. The lower costs can strengthen a journal’s competitive position as compared to other journals in the field. If a reduction in the number of submissions is still observed, however, the finding of Nwachukwu and colleagues that there was no change in the characteristics of submitted papers is important to take into account. If that is the case, the assumption that 1000 submissions are needed for 100 publications would remain unchanged.

New perspectives

A shift from publication-based charging to process-based charging may lead to better allocation of scholarly communication costs, lower charges per published article, and probably also a better consideration about the choice whether to publish and in which journal. The time seems ripe to introduce such a new APC model now that more and more journals are flipping to an OA model. Plan S requires authors to publish open access (and thus only submit to fully-OA journals), and there is a change going on in research assessment methods (i.e., from metrics-focused to narrative-focused). In particular, Coalition S is seeking pricing transparency for authors, and our proposed structure offers exactly that.

Looking at the stakeholders that are involved in scholarly communication, there is much to gain by changing the way scholarly communication is priced. The benefits for researchers are both transparency in the prices of delivered services by a publisher and lower costs per published article. Moreover, a researcher is triggered by the new APC model to make risk assessments and decide where to submit his/her manuscript: will it still be in that high Impact Factor journal with a long lead time and a small chance of being published? Or will more transparency and a change in the pricing model lead to less focus on Impact Factors, making other criteria more important when choosing an outlet? If so, this might help to shorten the time between first submission and publication, and reduce the hidden costs of rejection and the pressure on both the publishing and the peer-review process (in the example, assuming 2 reviewers per article, over 1300 reviews need to be made for 100 published articles in the end), leaving time for other important tasks.

Of course, we cannot ignore the fact that a potential roadblock in the transition to a new APC model is that journals might be less likely to introduce submission and peer-review fees if their competitors do not charge such fees. However, when the total article processing costs are taken into account, introducing these fees might be beneficial for a journal’s competitiveness as it enables authors to publish OA at a lower cost without sacrificing quality. Because the literature on the introduction of submission fees is not (yet) based on OA journals, we cannot predict which of the two scenarios is more likely to happen: a decline in the number of submitted manuscripts or a stabilization or increase because of the lower total APC costs ahead. In an earlier post on The Scholarly Kitchen, Tim Vines suggested to let authors choose between the new APC model (including a submission fee), or not paying a submission fee but paying a (higher) APC at acceptance of the paper. This suggested approach is not only a good solution for the transitional phase to the new APC model, but can also provide valuable insights into the effects of introducing a submission fee for an OA journal.

To us, changing the APC model now seems a much better idea than to wait until that ship has sailed while we end up in an OA world with undesirably high publication (as opposed to processing) charges. If you agree, join us in getting this message across to funders so they can publicly voice their support, and to publishers to help persuade them of the enormous benefits of transparency and fair pricing.

Discussion

33 Thoughts on "Guest Post: A Plea for Fairer Sharing of the True Costs of Publication"

Given the rise of transformative agreements, at least in Europe, I wonder if the approach you are proposing would have the effect of spreading publishing costs under these agreements to a somewhat broader array of institutions, for example in Germany beyond the U15. Had anyone tried to model that?

The assumption in the example is that the journal receives enough rejected submissions (900) to cover the majority of its costs from the submission fees and the peer-review fees to finally publish 100 articles, which means a 10% acceptance rate. In reality most of the OA journals have higher acceptance rates (around 50%) (See for example: https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2019.jul.07), only some of the most prestigious and selective OA journals such as Nature Communications have such low acceptance rates (and much higher prices).

One would adjust the numbers accordingly for each particular journal. Imposing a submission fee will likely result in an overall drop in submissions as well, so that has to be accounted for too.

It would be interesting to know what is the realistic cost to run an OA journal with 100 published articles per year. It seems that the actual numbers in the example can drastically change the total revenue.

I’m not sure there’s a singular answer to that question. It’s going to vary enormously from journal to journal. A journal that gets 1000 submissions per year and publishes 100 papers is going to have a very different cost structure than one that gets 100 submissions and publishes them all. A journal affiliated with a big publisher that can take advantage of scale and buy in bulk will have lower costs than an independent publisher that lacks the same purchasing power. A journal that tries to stay on top of the latest standards and technologies will have higher costs than a bare bones journal that ignores things like ORCID or proper tagging. A journal that does things like statistical editing or copyediting has different costs, not to mention the enormously different approaches in post-acceptance editing that go on in Humanities journals versus STM journals. I could go on, but I think that makes the point.

Thanks David, I totally get it. I just wanted to point out that the assumptions in the model are not really typical or realistic, which means that one should drastically change the assumed fees in order to get somewhere near to the expected revenues. I am not sure that the model would work that way: Most of the researchers would be reluctant to pay several hundreds of euros/dollars for submission fees and/or peer-review fees in advance, when the fate of their publication is still unsure. Or in the other case if the publisher raises the publication fee, we are almost back to square one: the current APC system, with a somewhat complicated extra pricing scheme on the top of it.

To be fair, there are already lots of journals with submission fees. The JBJS is mentioned in the post, and it’s pretty much the standard practice for Economics journals to name but a few. It’s not an unthinkable approach, and even with having to adjust the fees due to the drop in submissions, you’re still going to end up with a much lower overall payment for authors than just charging a straight APC. It may be the only way that many super-selective, high-end journals can exist in an author-pays world (many have suggested that they would otherwise need to charge an APC above $25K). It also has the significant benefit of lowering the effort burden on editors and peer reviewers, as ideally, people will make thoughtful decisions about where to submit, reducing the number of times a single paper has to be peer reviewed.

I’d be interested in seeing a study or at least hypothetical analysis on whether this proposal will favor established tenured (often grant and institutional-reputation “wealthy”) researchers at the expense of emerging researchers who because they lack reputation probably have to submit to more journals to get published. I’m thinking of the analogy to college admissions application fees. The rich legacy student needs only pay for one application because they know they’re almost certainly getting into that school. The poor “diversity” applicant with no connections and probably poorer information about what their likely prospects are at various schools has to pay for many more applications to be sure they get to go somewhere. In the college app world, fees can be waived for poor students. I could see amending the proposal in this post to allow for discounts/waivers for emerging researchers or those from smaller institutions (or developing countries).

That’s a really good point and a potential unintended consequence. You want any author-pays model to support a robust waiver program for authors without funding. But if you’re going to waive fees for emerging countries, then those costs are going to be paid by funded authors. That notion cuts against the philosophy here, that authors should only pay for the services they directly receive.

Why bother with the discussion? Why don’t you just do it? Start an OA journal with submission fees along the lines you propose. See what happens. If you are successful, you will significantly alter the field. If you are unsuccessful, you simply move on. Just do the experiment in the marketplace. Then your conclusions will be based on evidence.

Every (wo)man to his/her trade. An experiment as suggested should be conducted by a publishing company.

I think PeerJ experimented with a subscription based approach, intending to deal with many of the issues raised above. Their original model didn’t work, but they modified it. They’re still around and publishing (at least some) very good papers.

Sorry, I should clarify that it was originally an author-based subscription approach, which allowed submission of a certain number of articles per year.

It is interesting that discussions of slicing-and-dicing costs and spreading payments for OA articles usually stop at publication.

As a major scholarly hosting platform, we are paid by publishers to perform a large number of “post-publication” services. To name a few, maintaining the backbone software and bandwidth for delivering an OA article via the web worldwide (in perpetuity), meeting increasing accessibility, privacy, and speed standards, depositing metadata to an ever-growing number of aggregators and search engines (who like to change their deposit formats at random intervals), continually updating articles with citation tracking and usage reporting, enabling readers to create sophisticated personalized alerts, providing a TDM/API interface for programmatic examination of the articles (a growing use model), and more. I’ll stop there; I hope I’ve supported my point sufficiently — the costs for universally accessible OA articles integrated into the scholarly workflow don’t stop at publication.

If we’re truly going to line-item the “full cost of publishing” in an APC, I ask why stop at the moment of first publication? How about a yearly maintenance fee (in perpetuity?) covering the persistence of the article online and the services listed that have real ongoing cost? It would be a real shift of costs if a major OA publisher stopped publishing articles but was still on the hook to host articles previously accepted (in perpetuity? Sorry for the repetition!). One could make the case that they could just close up shop and someone else would take up the mantle (like LOCKSS or an aggregator, or libraries themselves) but there would be new costs for those players and no revenue to go with those costs in the current “payments stop at publication” model.

Of course, this perpetuity issue is not limited to the OA model, it is also present in the subscription model. But since the OA model is advocating a line-item examination of article costs, perhaps it will also drive us towards thinking more deeply about this “post-publication” cost issue.

Just have to point out that my library pays Portico a lot of money every year to pay those “close up shop” hosting costs, so there’s definitely revenue. But I like the idea of thinking about post-publication costs.

I’d say those post-publication costs would need to be included in the 3rd step of our model, as these apply to services of which only the authors whose manuscripts got published make use of.

Sorry, but I don’t think this is a good idea. Having authors pay less but more often is just a gift to predatory publishers. Instead of being able to basically go after APCs, they will now be able to go after submission fees, peer review fees, publication fees, copyediting fees, color figure fees, typesetting fees, bold/italics fees, page charges, reference list fees and more. And because less money will be involved with each fee – and no actual publication is necessarily expected after the first two fees – there will be less oversight and less accountability.

Plus getting three invoices for the one paper is going to be really annoying.

Please let the APC hit its evolutionary dead end already.

The main issue with predatory publishers is that they charge APCs for services they are actually not providing. Using submission fees as an income source would be more risky for a predatory journal than the current approach of charging an APC and publishing the paper asap (potentially after a poor review process), after which it cannot be published elsewhere anymore. When charging a submission fee, the journal could get revealed as being predatory before actual publication takes place and the other fees can no longer be charged.

This three-step-approach doesn’t necessarily have to lead to three invoices for the author. You could for example think about letting the author declare at submission that budget is available to cover the costs of each phase, and sending an invoice only after it is known for how many phases the author has to pay.

That’s not how it works. OA publishers generally won’t proceed until you pay. I assume it’s because they have lots of customers who don’t pay. If your article is accepted at, say, Frontiers, they will hold your proofs/publication until your APC is paid. If you submit to a journal with submission fees, they will not process your article until you pay your submission fee. Why would it be different for a peer review fee?

It’s not. except that the article isn’t published yet. In the current model, only the publishing stage is left when the invoice arrives. Most of the editorial effort has been done. So why should that be different? A publisher can send the invoice before the final act, or sooner if the process stops at stage 1 or 2.

“Moreover, a researcher is triggered by the new APC model to make risk assessments and decide where to submit his/her manuscript: will it still be in that high Impact Factor journal with a long lead time and a small chance of being published?”

Authors already choose to potentially delay publication, risk being scooped, and waste more of their time in trying to get into prestigious journals, as the rewards of publishing there are sufficient to outweigh these disadvantages. Adding a couple of hundred dollars to these costs won’t have much effect, especially if they are covered by schemes already in place to pay APCs.

“Or will more transparency and a change in the pricing model lead to less focus on Impact Factors, making other criteria more important when choosing an outlet?”

I just don’t see the logical connection here, sorry – I don’t believe the changes would have the least effect on general perceptions of desirability in publishing.

If this is the case, then why do journals that institute a submission fee see such a big drop in submissions (https://journals.lww.com/jbjsjournal/Abstract/2016/10050/The_Early_Impact_of_an_Administrative_Processing.13.aspx)?

Well, if I wanted to quibble, I’d point out that is one study, on one journal, which looked at a very limited time period only, and showed even a slight decrease in the quality of submitted Mss. (as judged by the percentage that were finally accepted – probably not statistically significant, although they don’t make that test explicitly). But instead, I will admit that I am sure there will be some effects – I was perhaps speaking overly generally, in order to make a point.

I do think though that the effect will likely be journal-specific, and that the more desirable a journal is perceived to be as a place to publish, the smaller the effect will be.

If I recall correctly from talking to JBJS when they did this, the sense was that the good submissions that stood a chance of being accepted still came in, but the garbage submissions largely went away. Most top journals have a significant desk rejection rate, and get tons of articles that are wildly out of scope or of astonishingly poor quality, and each one that gets submitted costs money, plus it uses up staff time, which also costs money. A lot of this is driven by countries that offer monetary rewards for publishing based on the journal’s impact factor. So researchers there send all of their papers to the highest impact factor journal they can find, regardless of suitability. It gets rejected and they send it to the second highest IF journal, and so on down the ladder until they get to an appropriate outlet (or just give up altogether). This eats up a huge amount of time and effort, both for editorial staff and peer reviewers, and the costs it causes are paid by subscribers or authors through APCs. If a small submission fee can lessen this bad behavior, then that’s a good thing.

“Imagine a university invoicing all graduating students for both the costs of their study program and the tuition fees of their peers who dropped out along the way. While this situation would strike most as unfair…”

The premise of this post is based on selfishness and the all too prevalent “what’s in it for me attitude” . In UK universities tuition fees are the same across the board whether you are taking a chemistry degree (lab costs, chemicals, glassware, safety equipment, instrumentation) or an English Degree (you still have to buy your own books!). From previous posts we know that the fees support university admin, library costs and a whole host of other costs – why should students pay these?

In fact, do my taxes pay only for me? I am very happy that my taxes support the welfare of others and creates a safety net for those who are down on their luck. My taxes also support international aid, of which i am proud.

Don’t get me wrong, I actually think submission fees are a reasonable idea and approach, but the attitude questioning why should i pay for others is objectionable. Most Society publishers are based on the premise of helping others through strong ethics, we are charities that support our profession so this attitude does not sit well.

I appreciate the logic of the idea, but it is, in effect, doubling down on a fundamentally unjust author-pays OA regime—one that erects barriers to authorship in place of barriers to readers. In the current APC system, if you’re not a grant-funded natural scientist, or employed in a rich institution or national system—which is to say, most scholars from the Global South, and humanities and social science scholars nearly everywhere—you are effectively blocked from publishing Gold or hybrid OA. This proposal just extends that income- and field-based authorship exclusion to the submission stage. (And the charity band-out of the current ramshackle, and unevenly available, APC wavier system will be just as flawed a fix if applied to the submission stage.)

I don’t think you’ll get much argument around here about the problematic nature of the APC author-pays model for open access. However, many funders seem intent on driving the market to that model as quickly as possible, rather than waiting for better models to emerge (I wrote about this here: https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2019/10/09/roadblocks-to-better-open-access-models/). Given that, if we’re going to have to deal with the APC/author-pays model, at least in the near term, are there ways to make it work better, and to reduce some of the issues it introduces. Submission fees do help in some areas — reducing expenses and workload, reducing overall spend by individual authors, allowing highly selective journals to continue to exist. They do not, as you note, solve the core issues of the APC model, and are at best a band-aid.

Thanks David: all good points.

As a retired physician without the option of a research institution funding any open-access submission, I either have to pay a substantial sum myself or abandon open-access altogether. However there is a worrying reverse to this coin. I submitted a paper to two (reputable) journals, and had the paper rejected, but was told in the same rejection email that I should re-submit to their open-access arm. There was an implicit suggestion that the article would be published, but of course that required payment. Thus a paper rejected by the print journal on peer review would be accepted for the open-access version. Double standrads. See Bamji AN, Cash for publication is discriminatory and unscientific. BMJ 2019; 365: l1915

I feel you should name and shame! This is outrageous. Unless there is a clear difference in acceptence policy so the rejection to the subscription title was based on scope or novelty that is not part of the OA title selection criteria?

Hi Andrew, we see this more often here at Maastricht University. We have Publish & Read licenses with almost all the large publishers for their hybrid journals. However, when our scholars publish in their OA titles, they often have to pay the APC. They usually have no funds and are not aware of this practice.

So when their manuscript is rejected and passed on to an OA title, they are often not aware of financial consequences. This was one of the reasons for us to think about APC awareness by splitting up the charges.

I do like the idea of passing on the manuscript with all the work being done, including peer review to another title, however this should not lead to unexpected costs. At least, publishers should inform the authors sufficiently.

I would like to follow Janine’s suggestion but don’t want to find myself blacklisted by the publications concerned, not least as a third publication accepted the article. However, if everyone flagged such an occurrence they would probably name themselves.

It is interesting that some traditional Chinese journals ask authors reviewing fee (about 30 USD) and publishing fee (different journal has different price), the total fee does not as high as OA journals, like plos one and scientific report, is it the same as what you mentioned? But many people still do not submit their research to these journal, for most researchers, the most important factor for choosing a journal is not the cost.