The United States Office for Science Technology and Policy (OSTP) is rumoured to be gearing up to release an Open Access (OA) policy, and like cOAlition S before it, both the funders involved and the researchers affected will need to consider different approaches to covering the costs of Article Processing Charges (APCs) that the majority of journals will charge to make an article OA.

Very selective journals need to charge a lot of money for APCs, mainly because the rare article that is accepted for publication has to cover the costs of assessing and rejecting 10, 20, or even 50 other manuscripts. Funders and institutions balk at these charges – often north of $4,000 – because they seem so disconnected from the apparent costs of publishing an article. Moreover, why should funders or institutions pay for peer review services delivered to other researchers?

As has been noted before, charging a submission fee and a publication fee is a fairer system, largely because authors cover the costs of reviewing and publishing their own articles. Authors are not responsible for costs incurred by anyone else’s submission, and the fees for each article are correspondingly much lower. For example, as I laid out in a previous post, one can approximate the APC at a wide range of journals through the formula (1/acceptance rate)*350 + 850. Authors of accepted articles only pay a $350 submission fee and $850 publication fee, for a total of $1200, even at selective journals with very low acceptance rates. For a 25% acceptance rate, the equivalent APC without a submission fee would be around $2250, for a 10% acceptance rate the APC would be $4350.

However, there is widespread apprehension that introducing submission fees will deter authors from submitting to fee-charging journals in favor of those that don’t have such charges. Editorial rejections are a big driver of this concern: it is frustrating to spend several hundred dollars to submit your article only to have it back in your inbox within ninety minutes. This situation can be alleviated by further separating the fees into a small submission fee, a fee for peer review, and a fee to cover the costs of publishing the accepted article (see an upcoming Scholarly Kitchen post for a proposal about this). Nonetheless, there is a world of difference between free and every other amount, and even a very small mandatory submission fee may deter authors.

An alternative is to give authors a choice of how they pay for their article:

- Pay a submission fee to cover peer review, with an additional publication fee if their article is accepted, or

- Submit for free, but pay a (much higher) APC if their article is accepted

Offering this choice could be a simple way to bring journals into compliance with funder APC caps: affected researchers can choose the submission & publication fee (hereafter “sub/pub”) option, which should always be lower than the straight APC.

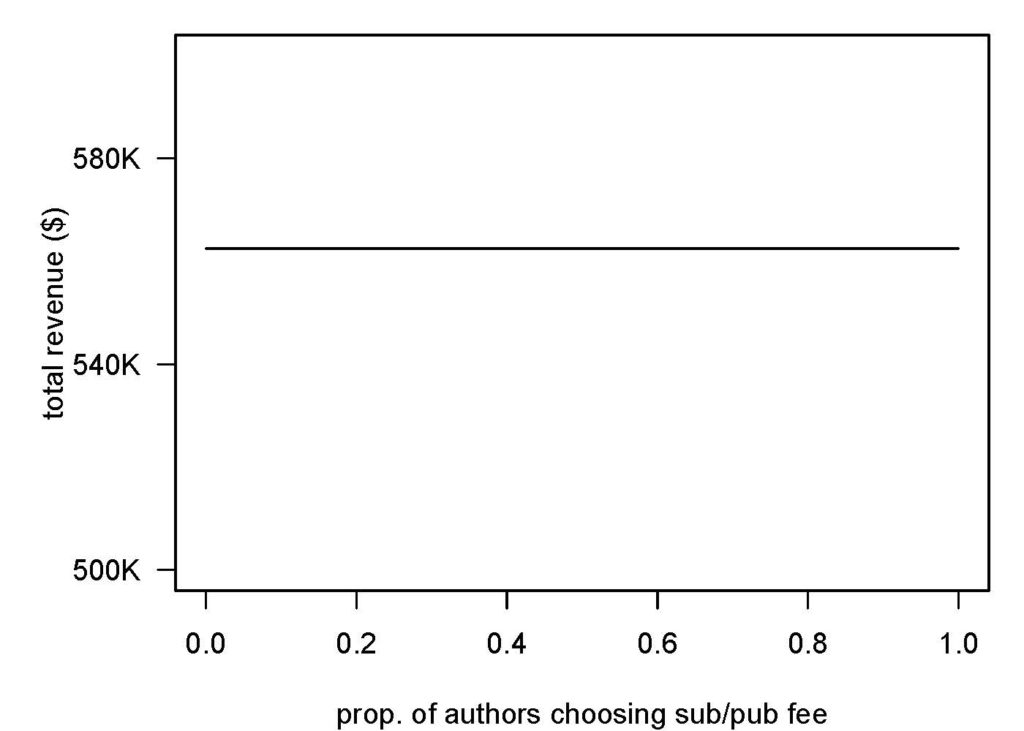

How does offering this choice affect journal revenue? At first blush, it doesn’t have much effect. As long as (1/acceptance rate * submission fee) + publication fee = APC, total revenue remains about the same no matter how many authors choose the sub/pub option.

As an example, imagine a journal with a 25% acceptance rate and a $2250 APC. For 1000 submissions and 250 published articles per year, total annual revenue would be $562,500. The option of $350 submission fee and a $850 publication fee maintains this revenue, even when everyone opts to pay the submission fee (see Figure below).

One way to understand this flat line is to picture (1/0.25) = 4 manuscripts being submitted under the APC option, and 4 coming in under the sub/pub option. In the APC case none of the articles pays a submission fee, and the one that is accepted pays the APC of $2250. In the sub/pub case, all four articles pay the submission fee (4 x $350 = $1400) and the one that gets accepted pays an additional publication fee of $850, for a total revenue of $2250.

The above assumes that authors are equally likely to choose either option. In reality, authors who are more confident that their article will get accepted should choose the sub/pub fee, as their total fee will be much less than the APC. Moreover, the higher quality of their work means their articles are less likely to receive a frustrating editorial rejection.

Authors who are less confident about their chances should choose the APC route, as their chances of having to eventually pay the APC are relatively low. People also tend to discount future fees compared to fees they have to pay right now. Opting for the APC also makes sense if your article has a higher chance of an editorial rejection.

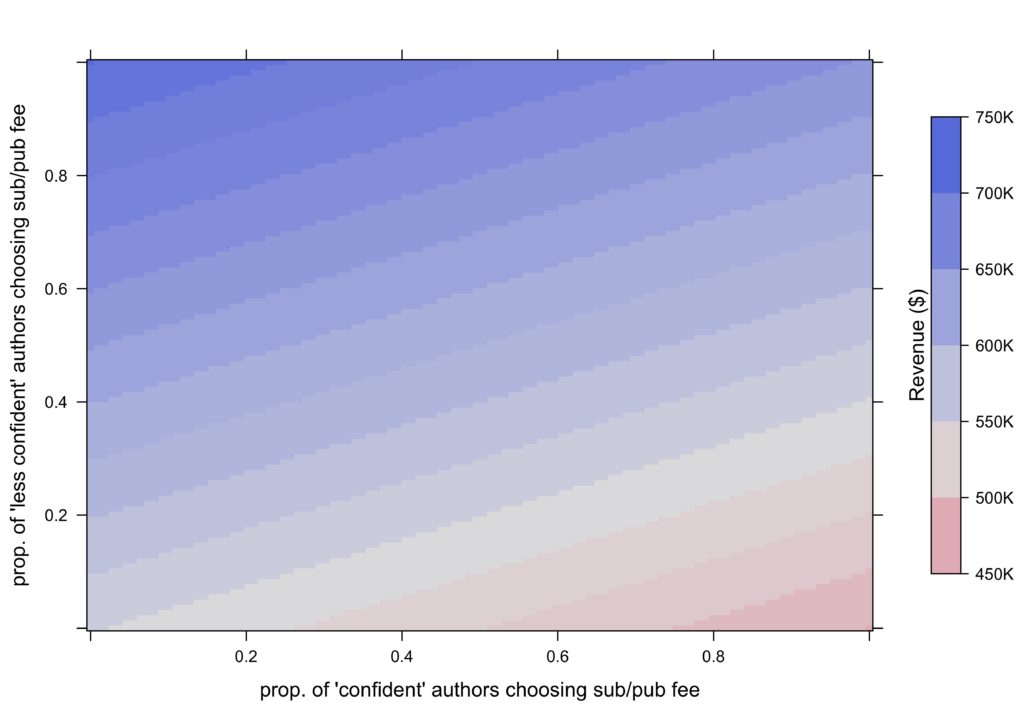

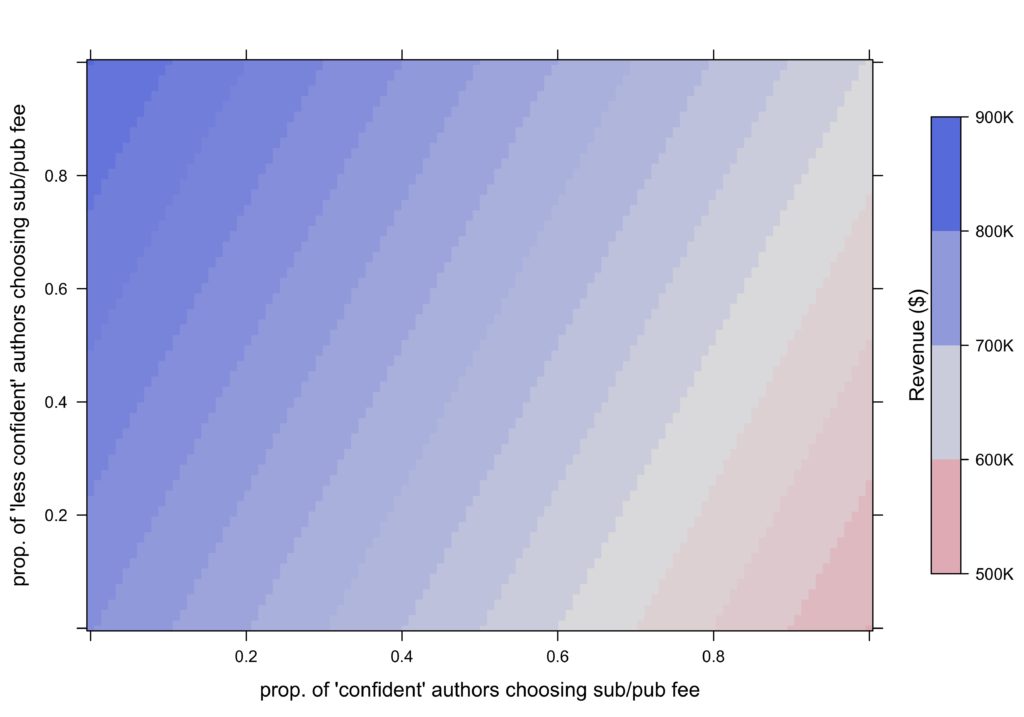

A crude way to approximate the effect of these choices on revenue is to divide authors into two groups. One group is ‘confident’ and submits work that is likely to be accepted (acceptance rate = 45%), and another group is ‘less confident’ and submits research that only rarely gets accepted (acceptance rate = 5%). If the journal receives 500 articles from each group, the overall acceptance rate is still 0.25. Again, the APC is $2250, the submission fee is $350, and the publication fee $850.

The figure below shows how total revenue changes as the confident and less confident groups increasingly choose to pay the sub/pub fees. The diagonal black line matches the line in the first figure above, where both groups choose the sub/pub fee at the same rate.

Below the diagonal line (red area) the journal receives less revenue, as here the confident authors are increasingly opting to pay the sub/pub fee. As their acceptance rate is close to 50% the journal only gets roughly $350 + $350 + $850 = $1550 per pair of these authors that choose the sub/pub route, rather than $2250 per pair from the APC.

Above the diagonal line (blue area), revenue increases as less confident authors increasingly choose the sub/pub fees – only 1 in 20 of these articles get accepted and therefore only 1 in 20 pays the APC. If instead these 20 articles choose the sub/pub fees, the total revenue is much higher (20 x $350 + $850 = $7850).

Given that confident authors are more motivated to choose the sub/pub fee, one would expect that introducing a choice of fee types would almost always decrease journal revenue (i.e. move it into the red area). This tendency can be ameliorated in the obvious way: increase the fees. The figure below shows total revenue when the submission fee is increased to $400 and the publication fee to $1050. Again, the red area indicates decreased revenue.

However, raising the sub/pub fees could deter confident authors from submitting their higher quality work to the journal, which is an undesirable outcome. Having a higher APC also boosts revenue: for an APC of $3000, even a 50% uptake of sub/pub fees by confident authors and 0% by less confident authors is still revenue neutral (see figure below, note the expanded revenue scale).

These analyses are admittedly simplistic – authors do not fall into two neat groups with very different acceptance rates, and many other factors feed into the calculation of APCs. The editorial office would need to be blinded from the author’s fee choice, allowing acceptance/rejection decisions to remain free from financial incentives. However, giving authors a choice between APCs and paying submission and publication fees does seem to have several strengths:

- Authors can publish in very selective OA journals without paying an exorbitant APC, increasing their accessibility

- Highly-selective, high-quality journals can maintain their standards of rigor without having to charge exorbitant APCs and excluding authors that can’t afford them

- This choice may provide a simple route for journals to comply with mandates that limit how much researchers can pay for publication.

- Since authors can still choose to submit for free, a journal can experiment with submission fees without losing authors to competing journals.

- Publishers can blunt criticism over the high costs of publication by allowing researchers to publish work in a wide range of journals for ~ $1200, which is less than the current APC at the biggest megajournals (currently $1790 at Scientific Reports, $1595 at PLOS ONE)

Who will take the plunge and try it out?

Discussion

46 Thoughts on "Let Authors Choose How to Pay for Peer Review and Publication"

I love the idea about authors choosing but I have to ask.. how serious are we about that? What’s the fine-print?

This whole article (and many others) rests on the idea that journals or more generally third-party publishers are necessary for knowledge exchange. If that’s the assumption where all of this is getting built on, that is effectively still marginal on the existing ecosystem. Not to mention the whole continuous (re)packaging and coupling registration and certification (re [paying for] peer-review… as if that can only be arrived through a journal).

Let’s compare: it costs about ~100 USD / year to have a personal domain and hosting – yes, it can be even at the fraction of a cost (hosting can be even $5 once up front for 20 years!) but I don’t want to scare people away from reality. Virtually unlimited number of individually-controlled units of information can be registered; universally accessible, interoperable, publicly archivable, reusable by standards-compliant applications, allowing social interactions, privacy respecting. Such resources can be anything, and goes beyond research articles and reviews. Just because something is registered, it doesn’t mean that it passed some quality-control. Certification and archiving remain orthogonal. People can self-publish reviews as well. Pretty crazy, I know… perhaps 2020 will be the year of the Web for scholars?

Everyone can self-publish ( https://csarven.ca/linked-research-decentralised-web#self-publishing ) on the Web, but we are told that’s not possible.

So, when you say “let authors choose”, who will take the plunge and try that out? [I can already hear the “yea, but” coming from the back].

US$100/year? That’s a bit much. US$10 for the domain and free hosting for static websites on Github is a bit better.

But what happens if you quit and stop maintaining your website? I guess you would then drop your papers in your institutional repository for free preservation. University librarians can often also register DOIs if you ask them for it. They probably won’t bill you the US$1 it costs them to do it either.

Don’t have a university library? Then get some friends together to publish your content on the same site, go to your library for your free ISSN and preserve your content via legal deposit for free. OK, so that would be a journal with an editorial board, but it’s better than paying to submit, then to be reviewed, then again to publish.

Go to your library for your free ISSN? Huh? Maybe really big institutions have such accounts with issn.org, but a lot of smaller ones like mine don’t. Having never gotten one before I just checked, and there seems to be a registration fee for publishers. https://www.issn.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/GuidelinesExtranetPublisherRegistration-ENG.pdf

>US$100/year? That’s a bit much. US$10 for the domain and free hosting for static websites on Github is a bit better.

I’ve ballparked a comprehensible number which is close to what a lot of people pay, myself included. It is still ridiculously cheaper than the average cost *per paper* via arbitrary publishers. Like I said:

>hosting can be even $5 once up front for 20 years!

Virtually no academic publisher can promise those numbers yet alone actually existing in 20 years.

>But what happens if you quit and stop maintaining your website? I guess you would then drop your papers in your institutional repository for free preservation.

Right. It is just registration. Any sense of real long term preservation comes down to archiving with societal or institutional backing. Orthogonal. I could also ask “what happens if publisher disappears?” Why is their corporate promise perceived or accepted to be any more legitimate than an individual’s? See also: https://csarven.ca/linked-research-decentralised-web#persistence-and-preservation .

Self-publishing (for registration, and among features that’s not even remotely possible by third-party publishers) is significantly less than what people are used to with third-party publishers. What’s saved can be re-allocated to institutional or public archiving, or just about any other feature or infrastructure improvement.

Anyone can be a “publisher” on the Web. It is not whether it is technically possible – for years 30 years now – or not but simply certain social forces are against it. It threatens their existence. If that wasn’t the case, why wouldn’t funders or institutions simply cover the $10, $100 or whatever per year for unlimited publishing instead of shelling out a couple of grands per paper? That’s rhetorical. Not to forget what’s relatively close to self-publishing is possible through many institutions today where they provide webspace to their faculty and students. If not, I’m certain that those that are capable of and willing to pay the the thousands per paper can re-invest on their own infrastructure to make it so.

This is not to say that third-party publishing shouldn’t be possible. The point is about choice and control. At the moment, authors are not given the possibility to self-publish and participate on equal grounds. If we can resolve that, I’d love to see how much those same publishers are able to charge to host a PDF on their website.

Researchers are able to do this now, either on their own sites or on pre-print servers. However, even in fields where pre-print servers are well established (e.g. maths), researchers still submit their work to journals in due course. It’s worth asking why they do that. As far as I can tell, it’s because appearing in a journal is the first step in having your work taken seriously – anyone can post online, but getting through peer review is much harder.

Tim,

>Just because something is registered, it doesn’t mean that it passed some quality-control. Certification and archiving remain orthogonal.

There is absolutely no technical barrier for a reviewer to self-publish and archive their review in response to an article (or its archived version), send notifications about their review to various inboxes, using interoperable protocols and data formats… have people discover all of that using their preferred applications. This is possible today, not hypothetical.

Certification is not something that can exclusively received through a journal.

>There is absolutely no technical barrier for a reviewer to self-publish and archive their review in response to an article (or its archived version)

Reviews of unpublished articles are considered ‘privileged communications’ between the reviewer and journal, so there is a powerful cultural barrier against posting these reviews. Anyone can comment on published articles or preprints, and they do (see e.g. Twitter), but that absolutely does not replace the structured peer review process.

>Certification is not something that can exclusively received through a journal.

I know, but that certification should still involve editor led peer review.

I don’t believe stating that all aspects of certification has to be public or that it shouldn’t involve an editor. Communities can make their own call on how they make it available and stamp.

Authenticating different actors and authorizing them for different units of information are simply orthogonal.

What you consider to be privileged communication may be important for some fields but it is not universal.

All kinds of actors (eg. authors, reviewers, editors) can participate with their own self-controlled online identities and registered resources, and can exchange notifications about their activities so that they can be discovered and reused.

The point wasn’t about changing the culture of quality-control but that centralisation and loss of control is not required. It can be done at the fraction of a cost with unmatched quality.

I think we’re at a point in time where ‘getting published’ can now carry many meanings. Yes you can get published online by self-hosting but to play a role in advancing research and academia in an already established institution of knowledge that has taken hundreds of years to shape, then peer-review is pivotal especially for citation and to allow others to use your work as credible source to build on; otherwise, what differentiates a random comment posted on social media to a piece of writing that took research, thought, synthesis and analysis?

I couldn’t agree more with the TO. What we really need is an open evolutionary system, where anyone can post its data (with due description of how they were obtained) and its interpretation. There would need to be a comment function where everyone else could leave its support or criticism but clearly associated with one’s name. Contrarily to a random post in SM, you would make a fool out of yourself if your data or interpretation were flawed or in error. On the other hand, to make a negative comment or to tear down other people’s work would have to be done in the open with all the risk that bears to one’s own reputation. So we could fix one of the drawbacks of the reviewing system (anonymous unjustified shooting in the back), and have also the advantage of the reception of the work being visible to people new in the field. Thus, we could fix the not uncommon situation that a set of data that has been found to be flawed is still accessible to people without the mention that the data are flawed (in the extreme case a printed version of a later withdrawn article). It is true that the academic system has taken hundreds of years to shape but during most of that time, means of communication were far away from what they are now. It’s like saying “Car industry did for over hundred years without Lithium batteries, so we should stick to the Diesel engines”.

What really will change is the ubiquous judgement of scientific quality of a researcher or institution by the publishing record proxy including impact factor and the like. We all know to what point this has created completely wrong incentive and it would be a good thing to abandon this for good.

I do like the idea, and definitely would be really interested to see what would happen if a publisher were to introduce a trial. (As a side-effect, it would also result in a much more transparent indication of what a publisher thinks a journal’s rejection rate “ought” to be.)

It would cause some issues though when it comes down to deciding who pays for the fees (and whether it should be the same source for both submission fees and APCs). For instance, I’m currently able to reclaim APC fees for most papers from my institution, depending on who funded the research; but I think that the widespread introduction of submission fees would be likely to cause some head-scratching, and potential conflicts of interest between researcher and employer.

In my experience, submission fees and APCs are counted as ‘publication costs’ by funders, and both are covered.

as long as submission+publication fee are invoiced as a single charge for accepted papers.

In my experience with Axios, funders always covered our ‘peer review fee’ without complaint, so there’s no need for a submission fee to be coupled to a publication fee. Bob Kiley just confirmed that Wellcome will cover submission fees: https://twitter.com/robertkiley/status/1217083118538100737

I agree that a submission fee is a good idea. Having to pay this fee should cause authors to be more contemplative about the topic, quality, depth, novelty, etc. of their manuscripts and find the journal that offers the best match and thus higher probability of acceptance. Reducing the total number of submissions, and thus increasing the acceptance rate, is in everyone’s best interest.

I envision some stumbling blocks, notably:

1. Unless pay-to-submit is globally adopted, submissions will continue to go to low or no-cost journals. In turn the expenses for these journals will rise, pushing up APC and/or subscription fees.

2. As Plan S has noted, judging authors by the impact factors of the journals continues to be the stumbling block to moving towards a more open science environment.

3. A pay-to-submit system will not reduce the perceived inequities of a pay-to-publish system compared to the pay-to-read system.

The fees will be a serious entrance barrier for people from developping countries. The figures that have been mentioned so far are peanuts to many of the institutions in Europe or North America but correspond to a month’s salary of the professor in an institution in Africa.

Nice analysis. Submission fees are indeed fundamentally important for a fair financial model in author pays OA, as otherwise the few accepted authors subsidize those submitting poorer quality or less exciting research. For journals with ~10% acceptance rates this becomes a big deal. Anything that makes submission fees more workable is therefore very welcome.

I agree that there has to be a sizeable financial incentive to ‘gamble’ on a submission fee. Two caveats are that even if you blind the editors to the route chosen (important point!) in our experience some authors will nonetheless perceive the need to look ‘confident’ so as not to disadvantage themselves in any way. I think this is the reason some authors opt out of being considered for inter-journal transfers at our journals.

A more minor point is that there is a real, defined cost to 1) editorially processing a paper pre- and post peer review + 2) publishing a paper. In the dual model, people will pay different total costs, which could be a little harder to reconcile with financial transparency (e.g. as PlanS is considering). However, I agree that if journal costs is reported in aggregate (as we do currently at EMBO Press) it would work, or one could report both routes.

As a publisher, I’d be concerned about authors taking option 2 (submitting for free), getting feedback via peer review, and then submitting the paper to another journal with a lower APC (where they now can feel confident their paper will be accepted).

A tenured prof in India makes about $5,000 per year. Thus, two articles comes to more than 10% of annual income. A tenured prof in China at a top STEM school makes about $15,000 per year. Although, submission fees paid by some in the west are insignificant it is not in the rest of the world…

So current APCs are already totally out of their reach as two articles would be more than their annual salary in India. Do OA publishers have special discounts now for researchers from such situations and/or developing countries? Maybe under a submission/pub fee option, the publishers would also have such a discount. I’m thinking of the analogy we in academe should all be familiar with, the fee students pay to apply to our universities. It prevents students from wasting admissions people’s time applying to lots of schools they aren’t seriously interested in or don’t have a serious chance of getting into. Often, poor students can get that fee waived.

I’ve always been a fan of submission fees–or any fee that creates an incentive to improve the matching between manuscripts and journals and to decrease long-shot submissions. Unfortunately, submission fees could further consolidate the publishing industry. Here’s why: A price-sensitive and rational author would be better off submitting to a larger publisher with a referral cascade (one submission, inevitable publication) over submitting to stand-alone journals (many submissions, uncertain publication).

Very true.

My journal (based in Latin America) has been charging submission fees (USD 100) since 2018 + a publication fee. We just raised the publication fee from USD 500 to USD 850 because the former amount was not enough to cover all journal costs (if anyone is interested, see here: https://www.medwave.cl/link.cgi/AuthorsCharges.act) (disclosure: the journal is 100% independent, no advertising and self-published).

We always need to charge a submission fee because there are too many authors who submit without actually reading author instructions; then, once their manuscript is accepted, they say they did not know they had to pay an APC. So to avoid this, charges come upfront, which is in the best interest of all parties, especially in a region that is not used to paying and where all journals are open access.

Since applying this policy, and as noted above by one of the commentators, we have fewer but better submissions. After two full years of charging, we are heading towards sustainability, and without losing our editorial independence. I can proudly say that we are publishing articles from Latin America and Spain 99% of the time.

While charging was a very tough decision to make, we had no other choice. We do not regret it.

The costs of assessing and rejecting manuscripts is zero for publishers. Why should authors pay for peer review? We are the ones doing the work of peer review, not the publisher. If anything, we should be paid for peer review. At the very least, all of our contributions as reviewers should count as payment towards having our own work reviewed.

Oh Sarah. This is patently false. To facilitate peer review effectively, systems are required, which costs money. To QC the manuscripts at every stage, staff is required. QC includes making sure manuscripts are complete before wasting reviewer time, making sure all required approvals are stated by authors, etc. Using tools like plagiarism detection software comes with an expense and staff with expertise to evaluate. To investigate any ethical issues that arise during peer review requires specially trained staff. To manage COIs between authors, editors, and reviewers requires staff oversight. Oh and there is financial support for editors that manage the editorial boards. If you know any journal editors, I would suggest you ask them about the support in technology and human capital they get for being a journal editor.

Really nice concise overview of what publishers do. Thank you, Angela!

Systems have fixed costs, they don’t increase with increased submissions. The idea of the article is that journals with high submissions have higher costs.

As Angela says, there’s a lot of staff time involved with managing peer review, and those staffing costs clearly increase as the number of manuscripts rises. Before we go much further with this discussion: can you identify any information or data that could change your mind here? If not, there’s not a lot we can do to improve your understanding.

In addition, many of the technology systems involved have a per-submission cost (ScholarOne and Editorial Manager charge per article submitted, iThenticate charges per article that gets screened, etc.). Stating that only fixed costs exist is not correct.

These peer review systems are the same as the submission system. The costs to publishers for them should not be portrayed to authors as separate.

I can assure you that Editorial Manager, iThenticate, Publons Reviewer Connect, image analysis programs, etc. are all separate systems with separate costs. But I think the per-submission costs of such systems are a relatively small portion of the costs (although each system does have substantial installation, maintenance, training, and re-training costs that need to be accounted for). As others have pointed out, the human costs are generally more expensive, as every paper requires at least some level of review by a human being, particularly because authors rarely follow instructions and each journal has individual requirements. Some of this has been alleviated through “format-free submissions” (or at least pushed back to the post-acceptance stage) but there are still a lot of journal-specific requirements that must be met and checked for (e.g., Genbank accession numbers for DNA sequence, dose:response curves for toxicity studies, etc.).

And then even where things are fairly automated, as Angela has pointed out, there are lots and lots of grey areas. You can have an automated system where an author enters their COI information, but someone has to review that information and determine whether it is adequate, as just one example.

There’s a surprising amount of complexity involved, which I’ve written about here: https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2017/12/20/end-aperta-journal-submission-systems-remain-challenging/

What I’m reacting to is the conflation of “peer review” with the administrative tasks that facilitate peer review. Publishers do not and cannot perform peer review. They perform administrative tasks that facilitate peer review. They should show respect and gratitude for the expertise and and reputations scholars lend to their work rather than trying to take credit for our work.

Sarah, I am an editor (no pay for that), and a peer reviewer (no pay for that). But running a journal as I do, please understand that the world does not begin nor end with editors and peer reviewers donating their time. There are may support systems and staff that have to paid a fair salary.

Of course I understand that.

Many, if not most, journals in my area (economics) have submission fees but are not open access. One problem with fees that are only paid on publication (something rare in my area) is that they create a conflict of interest for the journal. Any article rejected is revenue forgone. This is especially the case for journals that are only online (hence, there is no physical limitation in the number of articles that can be published). This conflict of interest is likely a bigger issue for new and lower quality journals, even if they don’t intend to be predatory.

At the end of the day, the cost of running a journal has to be paid either by subscribers or authors. Fees for authors are paid for the creation of knowledge. Fees for subscribers are basically paid for the consumption of knowledge. Either way, universities are going to be paying most of the cost either by reimbursing faculty for publication fees or libraries for subscriptions. The advantage of subscription fees is removing a conflict of interest for publishers.

The disadvantage being the paywall.

I always prefer to publish in free SCI- indexed journals.

The Canadian Medical Association Journal has just announced that they are going entirely paywall-free, and NOT increasing publication fees in exchange. https://cmajnews.com/2020/01/14/cmaj-drops-paywall/ Perhaps other non-profits should investigate how they can afford to do this.

I think the path to flipping journals to OA is going to be very different for enormous and wealthy organizations like the CMA than it is for smaller, niche research societies. CMA has over 75,000 members, and practicing physicians are generally a much wealthier membership than graduate students, postdocs, and university researchers. Membership revenue alone for CMA is likely to be vastly beyond what typical research societies see from all of their revenue channels, and the CMA also has a robust meetings program bringing in funds. I can’t say for sure, but I would bet that CMA has a diversified revenue portfolio, of which their journal is only a relatively small part.

Other societies may not be in as fortunate a position. There’s not quite as much money to be found from ornithologists or researchers of medieval literature, as there are fewer of them and they can’t afford the same level of dues and meeting registration fees. As such, they may be much more dependent on journal revenues for their existence, and subsequently unable to take the financial hit that the CMA is able to weather here.

I am not aware of any not-for-profit publishers that have NOT investigated this.

Because it doesn’t work. There is no business model that maintains revenue under these circumstances.