Editor’s Note: Today’s post is by Hong Zhou and Hiba Bishtawi. Hiba is Product Manager – Information Discovery at Atypon. Hong and Hiba are designing the new generation of conversational based discovery powered by GAI on the Atypon platform.

We all know that the ability to search for and find information quickly and efficiently is vital for researchers worldwide. And as we’re also aware, AI applications are increasingly transforming the way researchers do their work and interact with published content. But how is AI – and particularly generative AI – changing the way we find information?

In this post – the first of two discussing artificial intelligence and information discovery – we explore the evolution of information discovery, its role in the research journey, and how it can be applied to help researchers and publishers alike.

How have we seen information discovery evolve over the years?

The evolution of information discovery is certainly strongly correlated with the evolution of the web. First came Web 1.0, with its focus on delivering content in a typically read-only, static manner. Next up, the advent of Web 2.0 and the introduction of the information era, with a more interactive experience and read-write content.

As technology has advanced, Web 3.0 has enhanced the understanding and processing of information. We see a focus on the individual and a read-write-interact experience leveraging knowledge sharing. And now we move on to Web 4.0 – the intelligent web – which offers a much more personalized, collaborative, and user-centric experience.

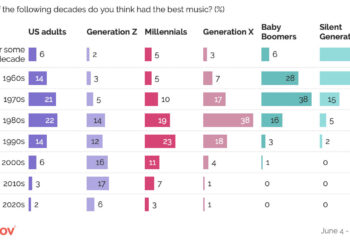

As you’ll see in the following graph, increasing amounts of data correlate to the advancement of technology, that enhances search productivity. We see a shift from a static, to a dynamic, then to a personalized content interaction experience, with the nature of the content evolving from just content, to information, then to knowledge-based results.

So what does information discovery mean for researchers and publishers?

Overwhelmed by information? You’re not alone! Like so many of us, researchers often get lost in the sheer amount of information that’s out there. And not only is it hard for them to keep up-to-date, it’s increasingly difficult to ensure the reliability of everything they consume. It’s often tricky to find relevant information, and to formulate the right questions needed to get to that information.

And publishers face challenges too – in enhancing the search experience on their platforms, maximizing user engagement and content discoverability, filtering out improper content, and finding the right audience and reviewers.

For researchers, information discovery is about far more than just search and recommendation. And to understand where AI can enhance information discovery and solve issues with practical applications, we first need to focus on the needs and uses cases of information discovery on the research and publication journeys. These include:

Direction and focus area: Choosing from the vastness of potential research areas is difficult. Which offer more long-term relevance? Does one area offer better career prospects than another?

Literature review: We already know that there are huge amounts of information out there. Researchers need to know what are most relevant and what they can trust, be able to read and digest quickly, and deal with any supporting and conflicting studies.

Hypothesis formation: Researchers need to formulate a hypothesis that’s both novel and feasible to investigate. Refining a hypothesis takes time and careful consideration.

Experiment and conclusion: Good quality data that can be trusted is vital. Researchers need to be sure they can find the right data for their experiment and they’re using the right analytical tools and interpreting results correctly.

Submission and review: With many thousands of journals to choose from, many researchers struggle to find the right home for their research. And when it comes to peer review – a vital stage of the publication journey – finding relevant reviewers is often difficult.

Publishing: Publishers need to ensure rich info/metadata are mined from publications and hosted in the right format to enable those publications to be more widely accessible, discoverable, and readable. The emphasis needs to be on the discoverability of knowledge, not content.

Discovery and dissemination: Audiences are looking for faster, broader, deeper, and more personalized discovery. Publishers need to be able to optimize discovery to the right audience and enhance their platforms to deliver the best user experience possible.

So, information discovery goes much deeper than a simple search! It aids in collaboration, referencing, reviewer selection, and detecting misconduct. And meticulous, properly formatted research, along with discoverability strategies like search engine optimization and metadata, enhances content accessibility and reach, ensuring true knowledge acquisition over mere content access.

Publishers’ own platforms: These provide an easy-to-use, comprehensive search functionality, and users can be sure of trusted, high-quality content. Experienced researchers usually know the specific publishers’ sites they should visit and can find full-text views of the research they need using specific search terms.

Public search engines: This is the most popular way for researchers to find content today. Researchers usually search content in search engines and click the link to jump to article pages directly. The biggest advantage of using public search engines is the huge amount of content they cover. Google Scholar supports basic search functionality but offers coverage of almost 389 million documents. Based on figures from 2003, around 79-90% of articles are published in English. Baidu is the most popular scholarly search engine in China, with 56% of the search engine market share.

Bibliography databases: One of the benefits of using these databases is for research analytics such as identifying research and business performance, research impact, and trends etc. Usually, a number of sorting options, categories, and dashboards are supported in each tool, enabling users to navigate and make sense of large sets of data efficiently. Scopus supports 27 subject areas with 334 subject classifications, while Web of Science supports 15 sorting options in 254 categories. Dimensions supports full-text search and currently has just over 42 million open access articles. Combining these search, sort, and filter functionalities into a single, streamlined interface makes it much easier for researchers to find what they need quickly.

Content aggregators: These include PubMed, which can handle sophisticated text-based queries as well as searches using medical subject headings (MeSh), and Semantic Scholar, which indexes over 206 million academic papers. Crossref is the largest digital object identifier registration agency of the international DOI Foundation; it has a metadata search and can match references to DOIs. With metadata available through Application Programming Interfaces (APIs), content aggregators facilitate integration with other systems. And with so much content indexed, these tools also enhance the dissemination of research worldwide.

In the era of generative artificial intelligence, new search tools and applications are emerging which we’ll explore further in our next post. But even before these developments, we can see how AI can be involved and applied in information discovery to help researchers:

Multimedia content discovery

Many publishers have leveraged AI to extract metadata from text, images, videos, data and other data elements to enable multimedia content discovery on their platforms.

Literature review and summarization

AI tools can help researchers summarize and extract key points from research articles, saving time and making it much easier to discover and digest large volumes of information.

Key research work identification

AI powered search can be used to automatically identify key publications and other information related to a specific topic to help junior researchers become familiar with particular areas. It also helps companies and investors better understand a targeted research area and its history.

Smart search understanding

Search can become smarter by incorporating domain specific synonyms, thesauruses for synonym-enriched discovery, fuzzy matching, and special character search in traditional ways. When we go to search, we might not always know the right keywords to use, or how to spell certain terms. AI can be used to better understand search queries and intention. For example, Google has already leveraged natural language processing to help the search function better understand search queries and return more useful information.

Recommendations and personalized news feeds

Most of us will be aware that AI can make content recommendations that are more relevant to your audience – we’re all familiar with the ‘people who read this article also read these ones’ model. In fact, recommendations are one of the most common applications of AI, enabling a more personalized user experience based on individual interests.

So what’s next for AI and information discovery?

We’ve seen how AI can be applied to aid information discovery across the research and publishing journey, from finding appropriate journals to disseminating content that’s relevant to the audience. AI has, and is, changing the way we get to the information we need.

When it comes to results, AI can connect a diverse range of sources to widen discovery – a win for researchers and publishers alike. It can also return deeper and more insightful knowledge, generating results in richer formats such as text, image, and video. And from a user experience perspective, AI will not only speed up information discovery, but also improve accuracy by better understanding users’ intentions and offering personalized results and recommendations. It makes information discovery more intelligent to help researchers not only find information but also complete research tasks with specific goals. And finally, as we’ll explore more in our next post, AI is introducing a huge shift, from the traditional ‘click’, to a more natural ‘talk.’ Users will no longer have to scroll through pages of results; instead, they can pose questions and receive direct, conversational answers with references.

AI is essentially orchestrating a transformation in the way we seek, understand, and engage with information, creating a more efficient, personalized, and interactive process. In our second post (coming soon!) exploring Generative AI and information discovery, we’ll take a deeper dive into conversational discovery, changes in solutions and methodologies, and risks as well as sharing some thoughts about future information discovery.

Discussion

6 Thoughts on "The Impact of AI on Information Discovery: From Information Gathering to Knowledge Application"

RE: “Publishers’ own platforms: These provide an easy-to-use, comprehensive search functionality, and users can be sure of trusted, high-quality content. Experienced researchers usually know the specific publishers’ sites they should visit and can find full-text views of the research they need using specific search terms.”

As a librarian, I (and I think many others) find a lot still lacking in the capabilities of publisher’s platforms. To highlight a few issues:

– Ebooks in particular are very often atomized, into a string of individual PDF files for chapters or sections. This makes searching for particular terms or phrases across the entire text very cumbersome, as one must search each PDF individually. (Kudos to Springer, for example, who provide whole-book PDFs; a much more useful format)

– Subject headings and vocabulary on publisher’s sites are often too broad to be very useful, and, they very often do not align with already-established subject standardization, such as the Library of Congress Subject Headings.

– For books and articles with accompanying media content, esp. those migrating from a print publication, it is often the case that the media content is simply jettisoned, or has dead links, or is not easily accessible or playable from the site.

Just to name a few… so, I think that there is ample room for improvement by publishers, before we get too excited about their capabilities.

Thank Nick for your insightful and detailed comment. Indeed there is ample room for improvement on publishers own platforms and other tools. The issues you mentioned such as PDF indexing and search, content classification and media content discovery are popular issues and many vendors including Atypon are working on these with AI. For example PDF parser, auto tagging and speech recognition…

Functions such as relevancy and accuracy and non functions such as scalability and reliability part are equally important to enable the powerful and useful discovery

Please see a correction in regard to Web of Science.

Web of Science provides expertly curated publisher neutral content across 254 categories and 15 sort options. We would appreciate it if this could be amended in the body text.

Thank you for the correction. It is not easy to get the accurate and most updated figures for other products in the market. There are so many different versions. We got the info from https://www.searchsmart.org/results/wos.corecollection?~(). We will keep an eye on these.

I’m interested to see how trustworthiness will be balanced with personalized results and recommendations, given that personalization is often led by marketing initiatives and for all the initial talk of taking a step back to truly understand what it is we’re actually doing with AI/to what end, the train seems to have left the station and is barreling full speed ahead. I hope that those with backgrounds in librarianship are on these teams developing AI tools for information search and discovery, as I’m not sure of another field that has for so long focused so deeply on information behavior without being driven by financial incentives.