There are many aspects to research integrity, from correctly attributing authorship to the creation of, or manipulation of data, to the application of large language models in writing the text. Each presents its own problems for policing the integrity of scholarly record. In turn, each has received significant attention recently as scholarly publishers grapple with their fundamental duty, which is to provide vetted, trusted research to the world. One thorny challenge has been the manipulation of images to buttress support of the argument presented in a research output. The work of a group image sleuths and even image assessment tools have been useful here, but it is insufficient. Fundamentally, scholarly publishing needs to address the problem of image integrity at scale and do so efficiently. The tools to do so exist, but they do need to be adapted for our community, and adopted in a way that doesn’t overburden either the researchers, the editors, or the publishing systems. This will require coordination among many different players, and concerted effort to apply these approaches consistently throughout the community.

Image Integrity has been an issue for centuries

This problem is neither new, nor unique to scholarly publishing. At the outset of the era of photography in the mid 19th century, one couldn’t always presume that the image that was shown was an accurate representation of the world, though for quite different reasons. For example, among the earliest daguerreotype plates is an image of a street in Paris taken by Louis Daguerre in 1838. Because of the long exposure time necessary to render the image, the street appears empty, save for two people. Although the throughfare would certainly have been teeming with people, carriages, and horses on a spring morning at 8:00am when the image was captured, none of these characters appear in the image. It would have taken four or five minutes for an image to set at the time using the process Daguerre was using. The pair of people, the first to be captured by any photographic process, were only captured by chance, as one stood while the other polished his boots thereby remaining in place long enough to register on the plate. The photograph appears to capture the scene perfectly, with the buildings more accurately presented than any painting might render them. Yet the image is no more representative of the real world than a Claude Monet painting of a Paris street.

Many old photographs have similar ghostly apparitions, or blurred scenes. Some took this to infer that photography provided some view of the ethereal or spiritual world. In the 1860s, the rise of “spiritual photography” was used to connect the living by inserting ghost-like images of the deceased into a photograph of the still-alive relative. Other aspects of spiritualism adopted photographic techniques of multiple exposure, cropping, dodging, or double printing, which can be used to alter the output a viewer will perceive. Various types of photomanipulation have persisted through the decades since and there are many famous examples of attempts to manipulate images.

Indeed, the ability of photographic techniques to capture non-visible light spectrum affects, such as infrared and ultraviolet which have proven so valuable in modern research were known to the scientific community in the 19th Century. In part this is what led many to advance the notion that this invisible world included spirits and ghosts, which photography could capture. Modern technology makes the notion of what can be trusted in a photograph even more challenging, since it requires far less mucking about with light, exposure and photosensitive chemicals. Since the advent of digital cameras, image manipulation has become easier and easier.

Much like the rest of the world, manipulation of images in scientific publication has long been an issue. Twenty years ago, an article by Helen Pearson in Nature described how digital image manipulation tools could allow bioscience researchers to tweak their data. In 2005, her article focused on the fine line between acceptable enhancements and scientific misconduct. Pearson’s article ends with a quote from Mike Rossner, at the time The Journal of Cell Biology’s managing editor, “We’re just fortunate that most students and postdocs are not that good in Photoshop yet.” Those days are very much long-gone. At the time, several journals were described as being in the process of developing plans for guidance on image submission that included submitting original images along with edited files. Another suggestion was to “demand that authors list the image adjustments they make in methods sections or figure legends.” Interestingly, these ideas are finally gaining traction in the much wider technology worlds.

Today in the era of images that are entirely fake, not simply edited or Photoshopped, it is vitally important that we make pains to ascertain the provenance and authenticity of content. In the face of this environment and the challenges it represents regarding image integrity, it is worth asking whether anything can be done. Do we just have to throw up our hands and accept that manipulated or faked images are ubiquitous and that we are powerless to stop their circulation? Absolutely not. The underlying technology already exists to create an effective system to ensure image authenticity and track an image’s provenance. We need to understand this landscape, apply existent tools to address this problem at scale, and collaborate across the research community to solve the problem. A report commissioned by STM and written by fellow Chef Phil Jones does an excellent job outlining the issues and considers potential solutions.

The Content Authenticity Initiative Approach

One possible solution described in the report is a relatively new project on content authenticity that has been gaining traction in some technology and media communities over the past several years. An excellent introduction to the Coalition for Content Provenance and Authenticity (C2PA) specification was provided by Leonard Rosenthol, Senior Principal Scientist, PDF Architect, and Content Authenticity Initiative Architect at Adobe. Rosenthal has led the technical development of the C2PA specification. C2PA was developed as a Linux Foundation Joint Development Foundation Project with a goal of developing a technical specification for establishing content provenance and authenticity at scale. The participants in this project have ranged from technology companies, hardware manufacturers, media companies, and creative organizations. Importantly, this project is not about detection, but rather about storing known signals of authenticity and data about provenance that can be associated with an object and tracked into the future. In this way, the efforts are different from — and potentially more effective than — the tools being developed to police fake images. While these are potentially valuable, this simply leads to an arms race with each side trying to improve their systems either to recognize or evade detection.

Trust signals are slightly different than the notion of proof. In information technology as in science, proof represents verifiable evidence or data supporting a claim. This is contrasted with trust signals, which are cues or elements that subtly build trust and credibility. In IT, a proof might be a digital signing certificate or a hash vale of a file. A trust signal might be metadata about a thing, a link to an ORCID profile, or links to previous vetted work. Trust signals are strengthened in a network of interconnections. In this way, C2PA is built around the idea that might be easy to fake an image, but far harder to replicate the chain of information that connects the device that captured the image, the software that processed it, the editing software that cropped it, and so on. This is like the notion that researchers should preregister their project and protocols, make public their grants, and share their data to create a research output. It is this package of objects that engenders trust, since each step is connected and can be verified.

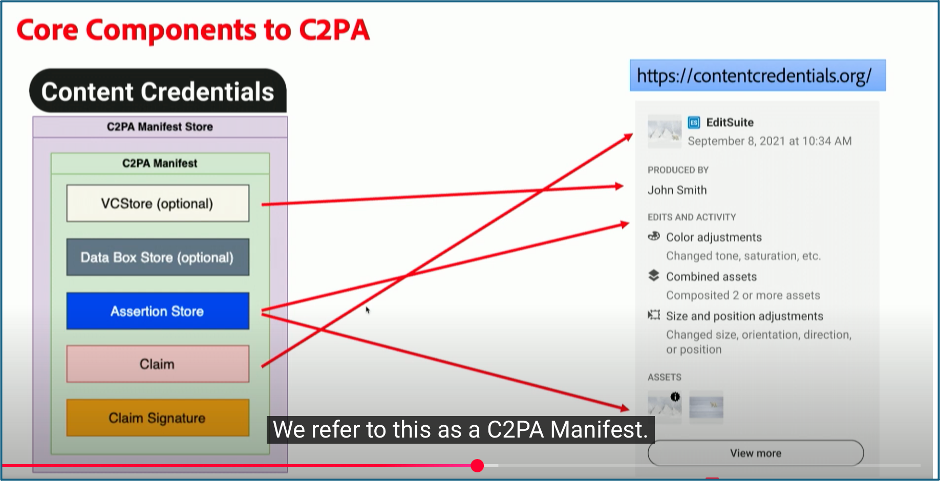

The specification outlines the technical details of how C2PA works. The notion that an object (image, text, video, etc.) will have associated Content Credentials is a core element of the C2PA protocol. This information is stored in a C2PA manifest. The screenshot below illustrates the kinds of information stored in the manifest and what kinds of information might be stored in this manifest package. This package includes facts about the content made by the creators, the assertions, such as the source, the location, the device, the copyright. These assertions are bundled into a “claim”, which is digitally signed by the creator. This can also be cryptographically connected to an identity as well. Ideally, Content Credentials will capture a detailed history of changes over time, so one can see what edits were made from the original to the current version, which too can be cryptographically verifiable. This functionality is optional but the more trust signals that are added to the content, the more trusted it can become.

Combined, Content Credentials use technology that makes it clear if content has been altered since its Content Credentials were created. The project has also developed a tool to compare images and verify existent content credentials. You can use their verify tool to see the content credentials at work. For example, the image used for this post was tagged using Content Credentials, so you can see its provenance. Drag and drop the image of the researcher featured at the top of this post into the tool. Not only can you see its original creation date, but you can see that I altered the original image. [NOTE (added on 3/13/25 a 9:45am EDT): A perfect example of how this process needs improvement and how metadata can be stripped breaking this system: After this post went live, I tested the above image. Frustratingly, the Content Credentials were stripped out of the file in the WordPress file management system. A screen shot of the credentials using the Verify tool display is included below.]

Work to improve content authenticity

Collectively however, this system is not perfect. For example, in 2023 Adobe was criticized for creating fake images generated by AI for sale of attacks in Gaza and Israel. However, it was obvious if one looked closely that the image was generated by AI. Relevant to this post however, was the fact that these images contained the Content Credentials metadata that stated the images were generated by AI tools. No one knew about, or thought to check, the provenance metadata. It will take time for people to adopt, create, recognize and use the trust marker systems like C2PA. Also, it is easy to strip away the metadata, say by breaking the chain of provenance data, say by screen captures or images of images. Potentially in time, people will also come to question the validity of resources that lack provenance information.

Within the scholarly community, this approach will require significant coordination and collaboration amongst the entire research community, from device manufacturers to software providers that process the resulting data and produce summary images, to article submission vendors and publishers. Jones outlines the steps required to make these systems work in his paper. This will be a significant effort, but the STM Association is exploring a potential pilot project. Interested parties should reach out directly to him. There will also be a panel about image integrity at the STM US Annual Meeting in April. This is but one element of the significant investment in this project. At present, the specification for the technology for C2PA is being formalized within ISO. US-based members of NISO can engage in the process and make comments on the draft. Those outside the US need to work through their own national standards bodies. There are also a variety of industry-specific partnerships that need to be developed and implemented for this to work in particular domains. For people who care about improving image integrity, there are presently lots of ways to engage.