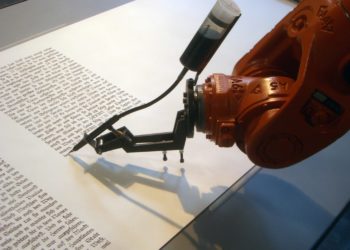

Artificial intelligence (AI) is transforming the academic landscape. It has become a powerful tool for researchers across disciplines and boundaries. From automating tedious literature reviews to analyzing complex datasets with unprecedented speed and precision, there is immense potential for what AI is able to do today.

But with each new feature, each new tool, isn’t there an undercurrent of resistance? Isn’t there discomfort, a distrust in the tool’s abilities and the ethical issues that arise from it? The industry often finds itself questioning the reliability of these tools. The distrust is not just in a tool’s abilities to perform, but in the ethical dilemmas it introduces. This unease is not unwarranted.

History has shown that disruptive technologies often face skepticism, particularly when they challenge deeply ingrained practices and values. Academic publishing processes have remained unchanged for years and the pace at which these changes are happening now is disrupting the industry and leading to skepticism. That’s probably because many of the AI innovations are not just at the surface, but instead are calling for an overhaul of the existing academic ecosystem — challenging each step of the journey itself. The way to overcome this resistance is not technical proficiency, but a commitment to fostering AI literacy and creating spaces to openly discuss its challenges and implications.

As we stand on the cusp of an AI-driven future, it is essential to move beyond resistance and engage thoughtfully with these technologies.

AI is not just a tool—it’s a paradigm shift in academic research and publishing. While skepticism is natural, fostering AI literacy is the key to harnessing its true potential. It’s essential to choose AI solutions that prioritize transparency, oversight, and responsible use—ensuring they assist rather than replace human judgment. The goal should be to empower researchers with intelligent support while preserving the critical thinking and decision-making that define academic excellence. — Nishchay Shah, Group CTO and EVP, Products & AI, Cactus Communications (CACTUS — full disclosure, my employer)

The question is how to ensure AI literacy and whose responsibility it is.

When it comes to responsibility and ensuring AI literacy, the onus is not on any one stakeholder. It must begin at the university level. After all, universities are at the forefront of shaping the next generation of researchers. But how much of this is already happening? Is AI literacy even a part of university curricula? Do we need courses that cover the fundamentals of AI, ethical use, and its interdisciplinary applications? How equipped are faculty with the necessary knowledge to teach AI effectively and to keep up with the latest updates on this front?

While it may sound far-fetched right now, can funding bodies wield their importance to shape research policies and encourage applicants to demonstrate how they plan to integrate AI into their projects and can this be included in the grant application itself?

Also, when it comes to publishers and journals, are they only responsible for integrating AI seamlessly into their workflows? Or are they also responsible for educating authors to use AI responsibly? And if yes, then what are the steps they can take to ensure this? Would creating guides, organizing trainings be enough? Or as journals start to use AI to streamline their workflows, can they create examples (e.g., videos) to demonstrate ethical usage of newly revamped processes that integrate AI? What sort of policing role must journals play in world where AI dominates the writing process?

Finally, how can researchers themselves play an active role in building their own AI competencies? The first step would be to stop fearing it and start embracing it. It is after all a tool to save time and to get more done. While challenges and ethical concerns undoubtedly exist, addressing these issues through responsible dialogue and feedback can drive the development of more sophisticated and reliable AI tools.

All of this is perhaps not as easy as it sounds. Many AI education programs focus on theoretical knowledge but fail to teach practical, real-world applications. Moreover, researchers in the humanities, arts, and social sciences are often left out of AI education initiatives, despite the growing relevance of AI in these areas. The fragmented nature of AI education further compounds this problem.

What I am rooting for is a collective shift in perspective. I envision a future that we don’t look at with apprehension, but with excitement about the possibilities and the opportunities AI offers.

Discussion

8 Thoughts on "Are We Fumbling in the Dark or Laying a Strong Foundation for AI Education?"

Roohi:

Thank you for this article, which is a good reminder for publishing organizations and others to instill AI training and literacy into professional development and author training. It’s my view that while more could be done, there is a high amount of AI literacy programing in scholarly publishing and publishing more widely. In our Graduate Program in Publishing at the George Washington University, we encourage our students to explore and understand AI tools, while considering myriad ethical considerations including copyright, among others. Barbara Kline Pope at Johns Hopkins University Press has been a proponent at the press and throughout the industry in this kind of exploration, with a human perspective—”a human in the loop at the beginning and the end,” and a goal of AI making jobs more productive, not replacing jobs. AI literacy has been a part of SSP, AUPresses, and other association annual meetings, webinars, TSK articles, and others. Thad McIlroy has written extensively on AI and publishing, and has co-hosted programs with PW and BISG on the topic. In terms of teaching, I recommend Jose Antonio Bowen and C. Edward Watson’s “Teaching with AI” (JHUP, 2024), which is inspiring and thought provoking.

AI literacy is, of course, a never ending goal, as is information literacy.

Thank you John. I completely agree with you that AI literacy is an ongoing goal and it is really encouraging to hear about the proactive steps being taken across different organizations and institutions. The collective efforts being made by universities, publishers, and industry professionals like yourself are already setting a strong foundation. Since AI is evolving so rapidly though, I feel that our approach to learning about it and teaching it also needs to continuously evolve. Thank you for the resource recommendations. I will be sure to check it out!

There are so many articles like this right now that call for “AI literacy” while also emphasizing the importance of AI users remaining cognizant of “ethical dilemmas” related to AI. To me, the rhetorical gesture has become close to meaningless, and I am skeptical of “AI literacy” as a project, because it feels like it is fundamentally about authorizing AI use above all else.

Could one be “AI literate” (or “AI competent”) or whatever we’re terming it and choose not to use GenAI tools for any variety of reasons? This doesn’t seem to be a scenario that “AI literacy” advocates often envision in their relentless push for widespread AI adoption and AI integration with a few box-checking gestures along the way in the direction of ethics.

I have doubts about whether literacy is even the right framework to be using for this technology. Another scholar that is skeptical of literacy in this context is Charles Logan, who presented a fantastic paper at the 18th International Conference of the Learning Sciences entitled “Learning About and Against Generative AI Through Mapping Generative AI’s Ecologies and Developing a Luddite Praxis.” To be clear: it’s not that I don’t think there is important learning that can happen when critically analyzing GenAI or perhaps using it, it’s just that I don’t see that learning in nearly as instrumentalist terms as AI literacy advocates do.

I think someone could absolutely be AI literate or competent and choose not to use AI tools, but it seems to me that publishing professionals, academics, and virtually everyone needs to know and understand how AI tools and platforms work, their limitations, biases, and possible benefits. It doesn’t seem that it’s one or the other: I’m “against” AI or I’m “for” AI, but rather when AI tools might be used and under what circumstances. It’s a bit, perhaps, like saying I’m against using a computer or against using a smart phone. There may be reasons for being against both of these, but ignorance should not, in my opinion, be the reason. I have always been skeptical of using the latest technology or device just because it’s there, and AI platforms definitely have a large amount of hype, but they are indubitably going to transform much of the workplace. Having expertise and skepticism are not incompatible.

You’ve made some very interesting points. It is true that AI literacy is often framed as an imperative for adoption. I feel like it goes beyond just AI adoption though. It’s true value lies in the ability to critically assess the tools, the impact, and its limitations. AI literacy is not just about how AI works but it is also about helping make informed decisions about when and how to use AI and when to resist its use altogether.

“What I am rooting for is a collective shift in perspective. I envision a future that we don’t look at with apprehension, but with excitement about the possibilities and the opportunities AI offers.”

“Also, when it comes to publishers and journals, are they only responsible for integrating AI seamlessly into their workflows?”

It would be helpful if you would define “AI”. If you are referring to LLMs, as we speak, publishers should be engaged in cleaning up their databases because the garbage is piling heavily already. I am not excited.

“If you are referring to LLMs, as we speak, publishers should be engaged in cleaning up their databases because the garbage is piling heavily already.”

I reply to myself by clarifying that by garbage I do not mean honest research with some mistakes here and there, but rather to true hallucinated garbage generated by LLMs. It is increasingly poisoning the scientific literature; already brief Google Scholar searches on the so-called tortured phrases reveal thousands (or tens of thousands) of post-2022 papers published by well-respected publishers. And these are then feeding back to the LLMs, which are increasingly integrated to the general purpose search engines.

When I peer review, I increasingly see also hallucinated (non-existent) references, among other related things. These cares are something publishers could easily handle, although I’d argue that they are about improving the meta-data infrastructure (DOIs, ORCiD, etc.) rather than about “AI”.

Granted, some “AI” things are already quite useful, among these recommender systems for academic papers. In this regard, Semantic Scholar already outpaces all major commercial publishers.

“AI is not just a tool—it’s a paradigm shift in academic research and publishing.” Right. Academic research and publishing are done in a way that is characterized by respect. We value the processes involved with reading and writing, critical and creative thinking. We honor those who went before us by citing and referencing their work. We work in a system of oversight and review from proposal through ethics approval through peer and editorial reviews. If something is incorrect, it can be retracted.

When we do research with participants, we minimize risks, we inform those involved of the benefits, expectations and risks, and we get their consent. Participation is always voluntary, and if someone changes their mind we have to remove their data from our set.

AI is done in a way that is characterized by disrespect. Copyright-protected writing and creative works are swallowed up, usually without the creator’s permission and without compensation. Our work is chopped up and mashed up with garbage scraped from the web. Our carefully crafted argument is torn asunder and bits thrown about out of context.

Of course it doesn’t always work perfectly, but let’s improve it, not turn it over to the tech titans who have been vocal about their alliances with authoritarians, and silent about the attacks on universities, libraries, academics and students who’ve been taken into custody based on their political views. They’re also quiet when it comes to the environmental costs of their playthings.

Scholars like to quote Isaac Newton’s observation that we “stand on the shoulders of giants.” I prefer that to standing on the backs of other writers.

I’ll stick with human literacy and human intelligence.