Science, as any other activity involving social collaboration, is subject to shifting fortunes. Difficult as the very notion may appear,…it is evident that science is not immune from attack, restraint, and repression. – Robert K. Merton, A Note on Science and Democracy

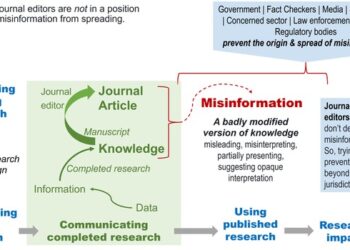

While much has been said about fake news and viral hoaxes, far less attention has been given to how disinformation shows up in science itself. We suggest misinformation and disinformation rear their Cerebian heads not just through manipulating publications and publishers, but gaming the entire scientific ecosystem – exploiting processes, structures, and norms in ways that may be technically permissible but ultimately distort the purpose of science.

Rick Anderson’s recent two-part column for the Kitchen on “Misinformation, Disinformation, and Scholarly Communication” poses the crucial question of, “How do we discriminate between the true, the false, and the misleading in science and scholarship?”

To make sense of this, we turn to taxonomies: tools that give us a shared language to describe what’s happening, based not on gut feeling or assumption, but on observable behaviors. Existing models (see examples from Zhou and Zhang, Wardle, White, and Kapantai et al.,) tend to look at social media and public misinformation, often focusing on intent. But the scholarly world needs something more precise.

A Taxonomy of Scientific Manipulation

Our work builds toward a taxonomy of scientific manipulation — one that asks: What does manipulation look like in scholarly work? Who’s involved? Where does it play out? And how do we name what we’re seeing? These questions drive our effort to map a more transparent, rigorous framework for naming, detecting, and understanding scientific norms and aberrations.

We sought to conceptualize how science is gamed, and interestingly, our taxonomy works similarly to a game of Clue/Cluedo. The primary structure comes from age-old questions of investigation — who did what, where, and how? In this case, it may be a professor, but unlikely Professor Plum, possibly in a library, but doubtfully with a candlestick or any other object in the mystery game.

To answer the who, where, and how science is gamed, we organized our taxonomy based on Actors, Outlets, and Methods. Actors are the individuals, organizations, and governments actively participating in the manipulation or strategic (mis)shaping of science communication, which may include the spread of false or misleading information. These actors leverage outlets such as journals, conferences/events, media, and institutions to carry their messages. Lastly, methods include tactics such as distorting scholarly communication norms, gamifying mainstream media, and/or leveraging the legal or bureaucratic systems to legitimize or obscure narratives. We started by identifying and defining subcategories for each based on how they manifest within scholarly communications.

We then branched these subcategories of Actors, Outlets, and Methods into more specific types. Individual actors can be scholars or non-scholars. When journals are used as an outlet to game science, the actor can knowingly choose to submit to an established journal like Science or to a vanity or predatory journal that works on a pay-to-publish model.

| Table 1: Scholarly Disinformation Taxonomy | ||

| Category | Subcategory | Definition and examples |

| Actors (Who) | Individuals | The individual who published or created the disinformation. Includes 2 types, for example: a scholar/researcher or non-scholar. |

| Organizations | The organization that published or created the disinformation. Includes 7 types, for example: a lobbying organization or a mimic organization. | |

| Governments | A government supported or created the disinformation. Includes 3 types. | |

| Outlets (Where) | Journals | Indicates if a journal was the mechanism for distributing the disinformation. Includes 3 types, for example: predatory journals. |

| Events | Indicates if an event was the mechanism for the distribution of disinformation. Includes 2 types, for example: scientific conferences. | |

| Media | Indicates if the media was the mechanism for the distribution of the mis/disinformation. Include 4 types, for example: social media or websites. | |

| Institutions | Indicates if an institution was the mechanism for distribution or leverage. Includes 3 types, for example: a political action committee. | |

| Methods (How) | Deceiving Scholarly Communication |

Deceiving scholarly communication was how the manipulation took place. Includes 3 events and 17 sub-events, for example: misrepresenting science/scholarship by fabricating data. |

| Gaming Mainstream Media |

Gaming mainstream media was how the information materialized. Includes 6 events, for example: emotionally charged headlines and spreading conspiracy theories. | |

| Leveraging Judicial System |

Leveraging the judicial system was how the manipulation was perpetuated. Includes 4 events, for example: misusing the law and lobbying activities. | |

The taxonomy provides a shared language, facilitates pattern detection, and identifies points of intervention. These three things put words into what we’re seeing happen to the scholarly landscape – and that clarity is what allows observation to become action.

- A taxonomy gives researchers, editors, policymakers, and the public common terms to describe what they’re seeing, without resorting to vague accusations or euphemisms.

- When behaviors are systematically named and recorded, trends and hotspots become visible. This allows us to go beyond anecdotes and toward evidence-based analyses.

- Knowing how and where manipulation occurs enables the design of more effective safeguards, incentives, and policy responses before problems escalate.

A Note About Intent

Manipulation within science is not a new phenomenon, but it is increasingly complex and, at times, obscured by the very systems meant to uphold integrity. Take open science. It was meant to foster trust through transparency, but openness alone doesn’t guarantee that the work, or the people behind it, are trustworthy. The system intended to improve scholarly integrity obscures manipulation in plain sight. To unquestioningly trust what’s open is at best naïve and at worst dangerous.

Developing a taxonomy is our way of making sense of this complexity. It helps us identify, name, and eventually mitigate the behaviors that undermine the credibility and purpose of science.

In this first version of the taxonomy, we focus deliberately on the what, who, where, and how of manipulation, not the why. While intent matters, it is notoriously difficult to assess. Misleading actions can stem from a wide range of motivations, including willful deceit or misplaced incentives.

To label something as disinformation implies an intention to deceive. But in practice, that’s a high bar. Some cases are obvious – citation cartels or coordinated paper mills, for example. Others, such as subtle forms of exaggeration or strategic omissions, live in the grey zone. Jumping too quickly to judge intent risks politicizing or weaponizing the taxonomy, undermining its utility and trustworthiness. That’s why we’ve chosen to prioritize observable behaviors over inferred motivations, for now.

Call to Action

Science should not be a game of strategy, but a process of discovery. Yet when dissemination systems are gamed, the integrity of that process is at risk. Our taxonomy is a first step toward reclaiming transparency and accountability within scholarly communication.

We invite you – scholars, editors, librarians, publishers, technologists, funders, and institutions – to join this effort. Help us refine, expand, and apply this framework. Share your observations. Challenge our assumptions. Most of all, help us protect the integrity of science, not just through ideals, but through concrete, collective action.

Let’s name the problem – then we can begin to solve it.

Discussion

3 Thoughts on "Guest Post — How Science Is Gamed"

Hi Leslie & Will.

Thank you! This is important work to my mind. Your taxonomy objectifies scholarly communications to a “If This, Then That” model – which could in itself, become an even higher bar for clear scholarly writing; however, I don’t think this is a bad thing.

One of my pet peeves in science writing are the papers that imply promising research findings in the article’s title while the same article’s conclusion, is a muddy “Further research needed” sentence. This always makes me wonder if the paper was gamed in some way.

Language constantly shifts and morphs into new new meanings, words and concepts so, concretizing a taxonomic framework for the how, what and who may be a good foundation on which to build better critical appraisal.

Your Taxonomy is a good start for precise communication, and that improved communication certainly advances science. Thank you. I will cite the taxonomy in an expose of misconduct.

Thank you Leslie for this interesting work. I certainly appreciate your desire to prioritize observable behaviors over inferred motivations. Though this probably leaves many readers (like me) curious if/how the various motivations might present differently in the framework of your taxonomy. Rick Anderson’s posts on Misinformation and Disinformation (which you linked to) just barely touches on this. I think it would be quite interesting to see some case studies or examples of manipulated science described using the taxonomy you have developed.