Editor’s Note: Today’s post is by Gareth Dyke, Academic Director at ReviewerCredits, Sales Director at 4Evolution, and co-founder of Sci-Train., and Ashotosh Ghildiyal, Vice President of Growth & Strategy at Integra.

Jeff Bezos once shared a valuable perspective: people frequently ask him what will change in the next 10 years, but rarely what will stay the same. He argued that understanding those things that will remain constant over time is often far more important than trying to predict what will change. This ‘Bezos Approach’ allows us to build more robust strategies and take long-term, confident action.

Applying this wisdom to scholarly publishing, we might ask: What is the one fundamental element that will not change in the future?

The answer is clear: Our society’s need to trust research will persist.

Regardless of technological advancements, the speed of communication, or the sophistication of AI, the public’s need for verified, credible scientific information remains constant. Science flourishes on trust, research propels human progress, and both depend entirely on the credibility of the knowledge we share. The question is: How will this knowledge be shared in the future? Will we continue to rely on traditional academic journals and books?

For journals, true value lies not in the volume of papers they publish, but in the trust they cultivate and their reputation for consistently publishing high-quality, meaningful research.

The Evolving Landscape of Peer Review

In an era defined by rapid-fire news cycles, fleeting attention spans, and the proliferation of AI-generated content, trust and attention are more valuable — and more fragile — than ever. In research publishing, this trust is rooted in peer review: the critical evaluation of research outputs by experts working in the same, or closely related, areas of study. Peer-reviewed research has long served as a crucial beacon of trust, a recognized seal of credibility.

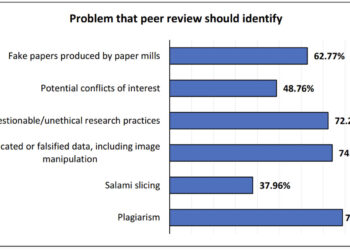

However, a significant challenge has emerged. Simply labelling an article as “peer reviewed” is no longer a sufficient guarantee of quality or reliability. Numerous issues in publishing and research integrity have come to the forefront in recent years — including paper mills, peer review rings, compromised editorial oversight, and even the use of AI to generate reviews or articles in their entirety. The reality is that the quality of peer review — including both the thoroughness of evaluation and the speed of the process — varies significantly across journals and academic disciplines. Likewise, the effort that editors and editorial office teams devote to identifying, inviting, and vetting reviewers is inconsistent, which can directly impact the reliability and rigor of the review process.

Superficial or inadequate peer review processes pose real and documented risks. They have repeatedly allowed flawed, misleading, or even fraudulent research to enter the public domain. When reviews are rushed, cursory, or conducted without sufficient expertise, critical errors go undetected, such as methodological flaws, statistical misinterpretations, and unsupported conclusions slip through the cracks. The consequences extend far beyond academia. Clinical guidelines may be informed by unreliable studies, policy decisions may be based on faulty evidence, and public trust in science can erode. The rigor and diligence of peer review are not optional — they are essential safeguards for both scientific integrity and societal well-being.

At the same time, AI is reshaping the peer review landscape. While artificial intelligence can enhance efficiency and flag potential issues that human reviewers might miss, it also raises serious concerns about preserving the critical judgment, nuance, and human expertise that robust evaluation demands. This convergence of systemic vulnerabilities and rapid technological change prompts a fundamental question: How can we ensure that peer review remains a genuine, trustworthy foundation for scholarly publishing?

A Necessary Evolution: Rating Peer Review Quality

To safeguard the essential trust in research, the system must evolve. We propose moving beyond the simple “peer reviewed” label toward a system where journals are rated based on the quality of their peer review processes.

Some journals are already experimenting with open peer review, where review reports are visible and quality can be collectively assessed. While not a complete solution, open peer review represents an important early attempt to address these dynamics and increase transparency.

Imagine a future where:

- Authors provide a ranking, or even structured feedback, on the review experience they received

- Peer reviewers assess the clarity, fairness, and thoroughness of the editorial handling process they have experienced at journals

- Readers contribute input on the usefulness, clarity, and reliability of published research, helping inform journal ratings.

- Independent third-party organizations audit and certify journals’ adherence to high peer review standards

In some ways, the seeds of such a system already exist. Reviewer recognition platforms and credit systems are beginning to acknowledge the time and effort reviewers invest. However, these initiatives often focus on acknowledging the volume of completed reviews rather than the quality of the review process itself.

We propose that a Peer Review Quality Rating could become a vital new signal, helping authors choose the most rigorous venues for their work and allowing readers, institutions, and funders to identify journals genuinely committed to scholarly integrity. By combining open peer review, structured feedback from authors, peer reviewers, and readers, and independent certification, such a system would offer a meaningful alternative to metrics like the oft-criticized Impact Factor, refocusing attention on the critical process that underpins trust.

Defining High-Quality Peer Review: Objective Criteria

For a peer review rating system to be credible and impactful, it must be built upon objective, transparent, and standardized criteria. What would define strong peer review quality within such a framework? What would you add to the list below?

We argue that key criteria (put together in a dashboard, for example) could include (in no specific order):

- Transparency: Clear disclosure of the specific peer review model used (e.g., single-blind, double-blind, open review) and explicit journal policies governing the process.

- Reviewer expertise and diversity: Demonstrable processes for selecting reviewers with appropriate disciplinary expertise (perhaps based on their previous peer review experience and/or publications) and a commitment to fostering diverse perspectives, including those from underrepresented geographies.

- Reviewer accountability: Mechanisms to encourage and ensure constructive, detailed, ethical, and timely reviews, potentially including feedback loops or periodic audits.

- Editorial oversight and engagement: Evidence of active editorial management of the peer review process, ensuring standards are met and reviewers are supported in providing feedback that helps improve manuscripts.

- AI disclosure: Transparent policies regarding the use of AI tools within the peer review workflow, ensuring AI serves as an assistant without replacing critical human evaluation.

- Process efficiency and depth: A demonstrated ability to balance reasonable turnaround times with thorough and high-quality evaluations (with clear disclosure of expected timeframes).

- Integrity protocols: Robust systems and checks to detect potential issues such as plagiarism, data manipulation, authorship conflicts, and other ethical violations.

- Post-publication responsiveness: Clear procedures and a track record of addressing concerns raised after publication, including issuing corrections, errata, or retractions when necessary.

- Reviewer training and support: Initiatives or resources provided to support reviewer education, best practices, and continuous improvement in the review process.

- Stakeholder feedback: Systematic collection and use of feedback from authors, reviewers, and editors to continuously monitor and enhance the quality of the peer review experience.

Applied consistently, these metrics would empower the scholarly community to distinguish journals where peer review is a rigorous process from those where it has become a mere formality. Some publishers already provide elements of this data, but nothing is standardized across the board. To achieve true consistency, industry bodies, scholarly associations, or trusted third-party vendors could play a pivotal role in developing a global peer review rating system that publishers across the board could adopt. Such a framework would not only create comparability and transparency but also establish a shared benchmark for what trustworthy, high-quality peer review should look like worldwide.

Preserving Peer Review Integrity in the Age of AI

AI is already influencing scholarly publishing, assisting with tasks such as manuscript screening, identifying potential issues, and summarizing content. When used thoughtfully, AI can undoubtedly enhance both the efficiency and the quality of peer review. For instance, it can flag possible image manipulation or statistical anomalies that human reviewers might miss, thereby helping to safeguard research integrity.

However, misuse or over-reliance on AI carries significant risks. It can erode quality, create blind spots, and accelerate the spread of unreliable information. Recent cases of AI-generated peer reviews being passed off as genuine underscore the dangers of unchecked automation.

This makes it essential for journals to establish transparent policies on where and how AI is applied within their workflows, accompanied by clear disclosure to authors, reviewers, and readers. Ethical guidelines and governance frameworks must evolve in parallel with the technology.

Ultimately, in an increasingly AI-driven future, holding journals accountable for the integrity and quality of their peer review becomes more critical than ever. Trust, fundamentally, cannot be automated. It must be earned, protected, and continuously reinforced through transparent, high-quality processes driven by human expertise and judgment, with AI serving only as a tool and not a substitute for that expertise.

Toward a More Trusted Future

The enduring constant in scholarly publishing is society’s need for trustworthy scientific information. Because trust is built on verification, peer review will always be essential, even as its methods evolve.

But the peer review process itself must be held to the highest possible standards. We must move beyond simply ticking the “peer reviewed” box. Just as in politics, where declaring a country to be a “democracy” does not make it one—actions, safeguards, and accountability must speak louder than words—so too in publishing, simply labeling an article as “peer reviewed” is no longer sufficient.

If left unchecked, peer review risks devolving into personal opinion diaries, partisan gatekeeping, or unchecked AI automation. Rating the quality of review is not optional—it is essential for the credibility of science itself.

Peer Review Quality Ratings offer a powerful step forward, promising to restore faith in the system, highlight exemplary practices, and ensure that robust, verified science continues to illuminate the path forward for humanity.

Our Question for Readers

If journals were rated based on the quality of their peer review, what criteria would be most important to you? Would you trust such a rating system more than traditional metrics like the Impact Factor? Please add your comments below.

Discussion

4 Thoughts on "Guest Post — Is It Enough to Say a Journal Is ‘Peer Reviewed’? The Case for Rating Journals Based on Peer Review Quality"

In my experience with the fringes of OA publications I have come across some very skimpy peer review. In essence one is often given just a couple of days, and also very often the manuscript in question changes little. And in my experience the other peer reviews listed were inadequate. And yet these journals claim to use peer review. I agree with some kind of scoring system, such as the number of reviews, the time allowed, and, yes, the response of the author in question.

Some quick comments from a friend who did not want to post them himself, but is a former academic …

Thank you for this paper—it is interesting and timely given the rise in AI and the increase in work-load of academics.

In terms of “Our questions for Readers” I would say

The quality of papers already published in a journal is more important than the Impact Factor(IF)—-to a scientist thinking of submitting a paper.

IFs are only a rough guide, but unfortunately they are used by funding panels in assessment of papers.

An alternative to IFs must be found as they are an unreliable measure of quality and can be manipulated

When seeking reviewers for a paper, “expert reviewers” should be found from a range of career stages and, in their review,

they should be asked to assess their confidence level of their review.

The article below may also be interesting/relevant

Great piece and there’s no denying, we need to do more to increase public trust in peer review. I think we have many of the tools at our disposal to do this – transparent peer review (publication of the reviewer reports) and publication facts labels are two examples that immediately spring to mind. On the point around authors reviewing their experience, I agree this would be a welcome addition. However I know from experience that authors can struggle to separate the quality of their experience from the outcome – if they were rejected they naturally report having a bad experience. But that doesn’t mean proper peer review wasn’t done. I would love to see a set of objective questions created that could be used to help with objectivity, e.g. how many reports did you receive, did the Editor offer additional guidance to complement the reports, were the reports constructive, if you reached out for support did you get a response within N days, etc. etc. An independent third party seems like the most effective and trustworthy approach to collecting and sharing this data.