Editor’s Note: Today’s post is by Ch. Mahmood Anwar. Dr. Anwar is a research consultant, editor, author, entrepreneur, and HR and project manager. His research interests include critical analysis of published business research, research methods, new constructs development and validation, theory development, business statistics, business ethics, and technology for business.

The conversation around generative artificial intelligence (AI) in scholarly publishing has moved rapidly, from breathless enthusiasm to cautious policy-making. While publishers and editors have swiftly reached a consensus position that AI tools do not qualify for authorship because they cannot take responsibility, manage conflicts of interest, or hold copyright, a more insidious problem is emerging: the new ghost in the scholarly machine.

The key ethical threat is not the listing of “ChatGPT” as an author, which most major publishers expressly forbid. The true crisis lies in the undeclared, pervasive use of large language models (LLMs) to generate substantive portions of a manuscript, e.g., the literature review, the portions of methodology, the discussion, or the framing of a conclusion. When a researcher submits an article that is significantly drafted by an LLM without clear disclosure, they are effectively engaging in a contemporary form of ghost authorship.

Defining the New Ghost

Traditional ghost authorship refers to a substantial contribution to a publication by an uncredited, often paid, human individual. It fundamentally breaches the core principle that academic authorship must honestly and accurately reflect contributions and accountability. If editors identify ghost authorship in any manuscript, COPE suggests adding missing authors to the list. However, AI should not be credited as a co-author.

Concealing generative AI’s role in providing content to a scholarly publication is an example of this ethical breach, but with a technological twist. When an author relies on an LLM to generate the intellectual content, rather than just to polish the language, they are outsourcing intellectual effort without attribution. This creates critical gaps in accountability:

- The Responsibility Gap — An LLM cannot be held accountable for fabricated data, plagiarized text, or “hallucinated” citations that it generates. The human author is ultimately responsible for the integrity of the entire work. Undisclosed reliance shields the contribution from scrutiny.

- The Transparency Gap — Scholarly communication relies on transparency to build trust. When a reader, editor, or reviewer encounters AI-generated text disguised as human thought, the foundational trust in the research process is compromised. It masks the true origin of the ideas and the effort invested.

The Problem of Pervasive Assistance

Most publisher policies distinguish between permissible and impermissible AI use. In most cases, AI is allowed for language and readability, but prohibited for generating, manipulating, or reporting original research data and results.

However, the middle ground — the narrative prose of the manuscript itself — is where these policies tend to break down. Is it merely “language improvement” to use an LLM to synthesize a literature review from ten uploaded papers, or to rewrite a complex results section to make it sound more authoritative?

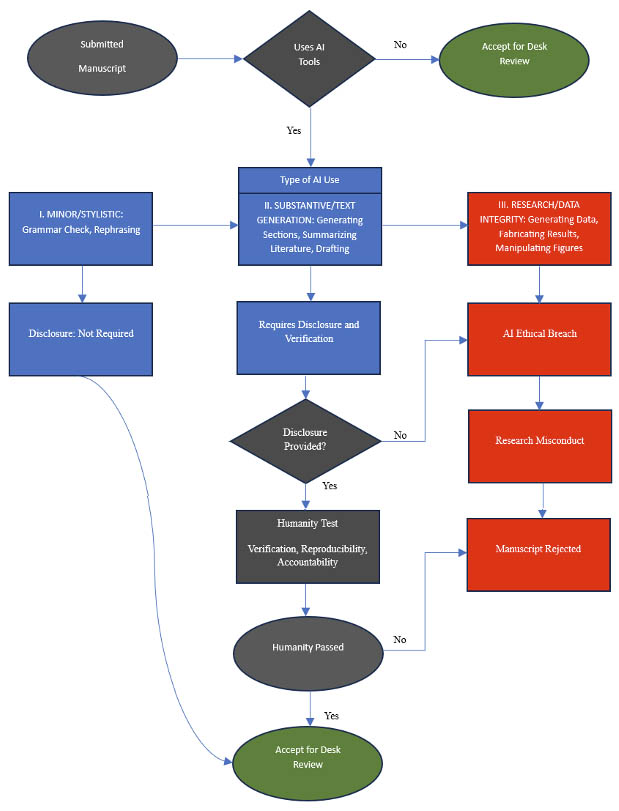

This distinction, which determines whether disclosure is necessary, is notoriously fuzzy. A helpful framework (devised by the author), informed by the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) position, suggests a spectrum of AI use presented in the table below.

| AI Use Category | Example Activity | Ethical Status & Disclosure Requirement |

| I. Minor/Stylistic | Proofreading, grammar correction, rephrasing for clarity, correcting the tone of a sentence. | Permissible. Disclosure generally not required. |

| II. Substantive/Text Generation | Generating full sections (e.g., Introduction, Discussion), summarizing literature, generating a complete draft from notes. | Permissible only with full disclosure and human verification. Failure to disclose is the new ghost authorship. |

| III. Research/Data Integrity | Generating research data, fabricating results, manipulating figures, writing code for novel analysis. | Unacceptable and a breach of research integrity. |

As seen in Category II, the ghost writer is not an uncredited human, but an uncredited algorithm that provided the structural framework and authoritative prose for the argument, leaving the human author as merely the final editor and submitter. Figure 1 provides the flow diagram for editors to check submitted manuscript for AI content and making desk decisions.

The Path Forward: Mandated Transparency and Policy Harmonization

To mitigate the threat of AI ghost authorship, the scholarly community needs to move past simple prohibition and toward mandated transparency, which the APA is now recommending for authors.

- Standardized Disclosure Statements: Publishers must harmonize their requirements, perhaps using a CRediT-style taxonomy for LLM contributions (e.g., “Drafting – LLM-Assisted, 70% of Introduction”). This would provide the necessary granular detail beyond a simple “AI was used” type generic statements. For instance, Taylor and Francis request that authors include the full name of the tool used (with version number), how it was used, and the reason for use. Similarly, Elsevier urges authors to document their use of AI, including the name of the AI Tool used, the purpose of the use, and the extent of their oversight. However, the extent of AI assistance in idea conceptualization, drafting various section of manuscript, and the boundary conditions are rarely documented.

- Citation of Prompts: When substantive content is generated, the human-authored prompt must be disclosed, either in the methods section or in a supplementary appendix. This allows reviewers and readers to understand the human’s intellectual input versus the machine’s output.

- The “Humanity Test”: Humanity test is the term devised by the author to refer the accountability and verification requirement. Authors must be able to verify, reproduce, and take accountability for the content generated by the AI.If a section is so wholly machine-generated that the human author cannot defend its core claims or trace its sources, it fails the requirement for human accountability and must be rewritten or fully substantiated by the authors.

The challenge posed by generative AI is not just technical; it is a fundamental test of the publishing industry’s commitment to the principles of accountability, integrity, and transparency. If scholarly publishing allows the new “ghost in the machine” to persist through a lack of clear and enforceable disclosure, the trust underpinning the entire system will be irrevocably diminished. The tools are here; the ethics must catch up.

Discussion

17 Thoughts on "Guest Post — The Ghost in the Machine: Why Generative AI is a Crisis of Authorship, Not Just a Tool"

An excellent and timely reflection by Ch. Mahmood Anwar. This piece strikes at the heart of the current technological shift by distinguishing between utility and identity. While we often frame the AI debate around ‘efficiency,’ Anwar correctly identifies that the real sacrifice might be the ‘human spark’—the lived experience that gives art its weight.

The ‘Ghost in the Machine’ isn’t just a metaphor for automation; it’s a challenge to our definition of originality. If we decouple the struggle of creation from the final product, we risk a future of ‘perfect’ content that says absolutely nothing. A deeply necessary read for anyone concerned with the preservation of human-centric authorship.”

Thank you for your supportive comment.

Thank you all for sharing!

timely and thought-provoking piece. It clearly highlights that the real risk of generative AI in research is not the tool itself, but the lack of transparency and accountability in its use. The emphasis on disclosure and human responsibility is especially important for protecting trust and integrity in scholarly publishing.

Yes, human is responsible not AI. Editors should follow the suggested flow diagram and test.

This is a good time to discuss the issue in this way. The work by Dr. Mahmood Anwar is commendable; it not only highlights the problem but also proposes practical solutions for editors. I hope the handlers will take it seriously and work towards safeguarding academic research.

On the other side, we also need to accept the reality of AI’s presence and focus on developing ways to identify genuine scholarly contributions, particularly in social sciences research. May be a future article on that would be an interesting read.

Thanks for appreciation. Yes, future works must consider it.

Ya, it’s true “academic authorship must honestly and accurately reflect contributions and accountability.”

Very true.

You write “Authors must be able to verify, reproduce, and take accountability for the content generated by the AI.”

How can an author reproduce something AI has produced when AI’s output, even with the same prompt, differs with each use.

What if one creates a code in Django and can’t reproduce in front of you? If he can’t, simply he fails the humanity test.

Very comprehensive and thought provoking

Thanks for reading.

Enough! Readers need to be able to trust scholarly research in a world of disinformation, misinformation, and fakes. It is time for scholars to raise the standards for excellence and stand up for integrity. Use your own intelligence, not regurgitated slop that inserts fantastical citations. If you do not want to read, think, and write, there are other jobs you can do. If you are going to submit scholarly writing, put in the attention and effort required to make an authentic contribution.

As Jowsey et al (2025) note, it is time for researchers to reject the “exploitative, colonialist, and extractivist practices in which big AI corporations engage, which have harmful impacts on humans and the planet.” While as they note this is particularly crucial for qualitative researchers, I think their point is on the mark generally.

Transparency would useful if those who confuse spitting something out from an LLM with writing would put into the abstract something like “I was too lazy to write this article myself so I used AI.” That way I can go to the next article, one whose methods and findings I can trust.

Jowsey, T., Braun, V., Clarke, V., Lupton, D., & Fine, M. (2025). We Reject the Use of Generative Artificial Intelligence for Reflexive Qualitative Research. Qualitative Inquiry, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/10778004251401851

Yes. 🙂 With the advancement of science, people become lazy. In the world where people are fond of short cuts, Gen. AI offers more than merely a short cut. The credit also goes to companies which are making people lazy just to maximize their economic rents. AI was working very fine for years in the areas of industrial electronics, quantum physics, robotics etc. But advent of Gen. AI has ruined the scientific landscape.

Very interesting and thought provoking article

Thanks for reading and commenting my friend Prof. Dr. Dyke.