Editor’s note: Today’s post is by Chef Tim Vines and Ben Kaube, Adam Day, and Kristen Ratan. Ben is a cofounder of Cassyni. Adam is CEO of Clear Skies Ltd. Kristen is the Principal of Strategies for Open Science (Stratos).

Back in April 2024, Tim Vines and Ben Kaube put together a Scholarly Kitchen post that took the concept of honest signalling — a theory for why animals have elaborate courtship displays and bright breeding colors — and applied it to research integrity.

If you have time, it’s probably worth reading that earlier post before diving into this one. In brief, much like the elaborate colors and dances of (for example) the male bowerbird, we argued that researchers who are confident in the robustness of their work and willing to have it scrutinized are more likely to engage in these costly, visible practices.

Conversely, researchers whose work is merely “good enough” to satisfy minimal publication requirements — or worse, those engaged in fabrication or papermill activity — have strong incentives to avoid situations where their work might attract closer attention. As we put it at the time:

“These signals, akin to the peacock’s tail, are not just markers of the quality and credibility of the individual’s work but also serve to signal their commitment to the principles of research integrity.”

That earlier piece was primarily theoretical. In this post, we ask a more concrete question: Does the data support this framing? In particular, are open science behaviors really less common in articles that are associated with papermills?

Measuring Open Practices at Scale

To capture open science behaviors, we draw on the PLOS Open Science Indicators (OSI) v10 dataset, which includes measures of code sharing, citation of author-generated protocols, preregistration, and preprinting. The dataset covers approximately 139,000 PLOS research articles published since 2018, along with a comparator set of roughly 38,000 articles drawn from PubMed Central.

The OSI dataset also includes a data sharing indicator, but (unfortunately) that indicator records ‘Data Shared = Yes’ both for articles that reuse existing public datasets and properly cite them and articles that generate new data and deposit them in public repositories. Since many papermill articles rely on recycled analyses of large public resources (e.g. NHANES data), we need to home in on articles that a) genuinely generate new data, and b) do or don’t share that data on a public repository.

We therefore assessed data sharing across the PLOS and comparator corpora using DataSeer’s newer LLM-based methodology, developed in conjunction with PLOS with input from the open science community (and which will be released later in 2026). The new methodology is able to reliably distinguish between public sharing of newly generated datasets and reuse of existing data. This allows us to focus specifically on behaviors that reflect a willingness to expose new research outputs to external scrutiny.

Presentations as a High-Confidence Integrity Signal

A powerful but often overlooked signal of research integrity is whether authors have presented their work at conferences or institutional seminars. Traveling to a conference is expensive; putting together a high-quality presentation is a major time investment. Researchers expending all these resources so that their peers can ask awkward questions must be committed — financially and morally — to doing high-quality research.

Using data from Cassyni, we identify research talks associated with published papers by aggregating presentation records from university seminar series, conference websites, and other established scholarly sources on the open web. Candidate matches were then evaluated by an LLM that compares paper metadata (title, authors, publication date) against presentation details in a process specifically tuned for high-confidence matching. This approach makes it feasible, for the first time, to assess presentation activity as a scalable and verifiable component of editorial evaluation. Using Cassyni’s technology, we assessed whether a subset of 6629 PLOS articles was associated with a conference presentation.

Capturing Research Integrity

For our measure of Research Integrity, we use Clear Skies’ Papermill Alarm. The Papermill Alarm blends LLMs with network analysis to assess the risk of retraction for papermill activity for a given research article, and produces alerts using a traffic-light system:

- Green – very low similarity to papermill articles

- Orange – some similarity to papermill articles

- Red – high similarity to papermill articles. Tuned for a near-zero false-positive rate.

For the PLOS corpus, 1,446 articles were flagged as ‘red’ by Papermill Alarm, and a further 1,757 were flagged ‘orange’, leaving 104,344 as ‘green’. For the PMC Comparator corpus, 976 were ‘red’, 572 were ‘orange’, and 20,471 were ‘green’.

The overall results are shown below, note the different y-axis scales between the two figures.

Some behaviors were common overall. For example, sharing new data online occurs in 31.6% of articles that generated data. Nonetheless, there is still a substantial difference in data sharing between potential papermill articles (15% for red and 19% for orange) and non-papermill articles (32% for green).

Other open science behaviours were much rarer. Only 182 of the 6629 articles we examined were associated with a conference presentation or departmental seminar (2.7%). However, presentations were extremely rare among red and orange articles (1 and 0, respectively, or 0.7% and 0%), and the majority were associated with green articles (181, or 2.83%). Presentations are thus almost exclusively associated with legitimate articles.

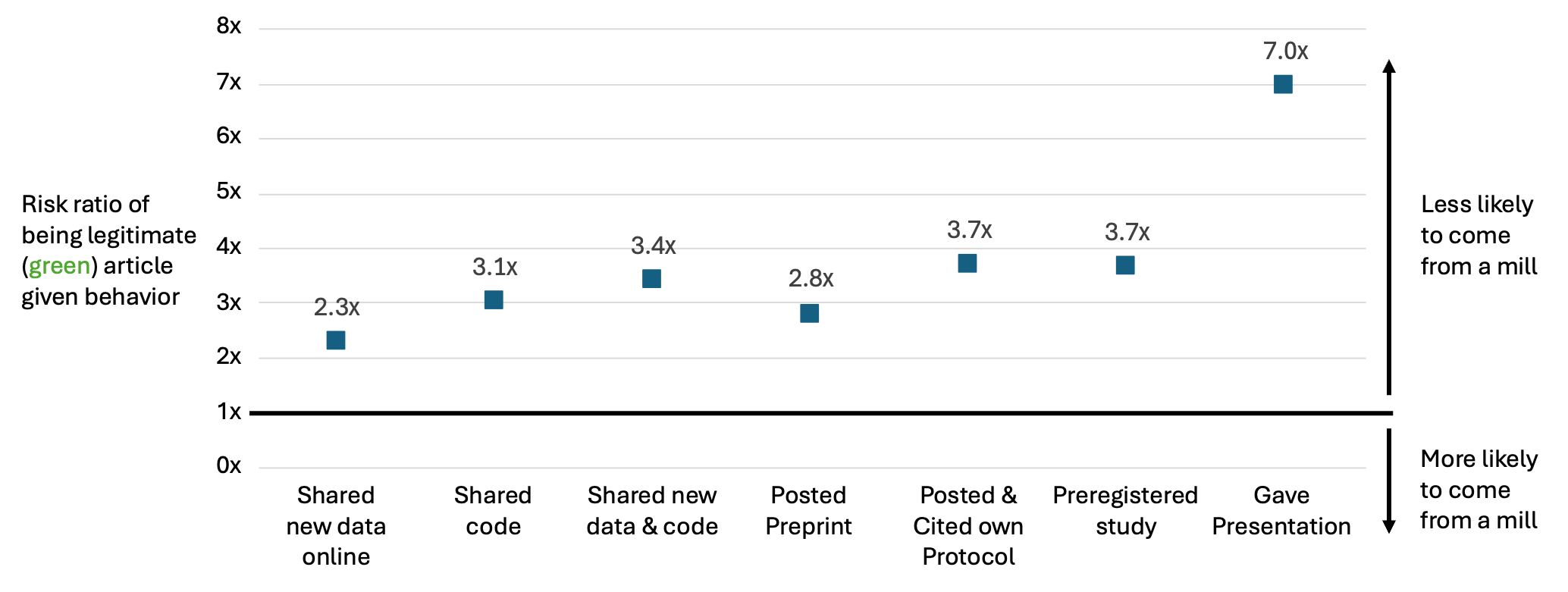

From an editorial perspective, it’s less relevant to ask “how often do papermill articles share data?” But, rather: “given a newly submitted manuscript, how useful are these signals in spotting milled articles?”

To get a handle on this, we convert the proportions from the figures above into ‘risk ratios’. These ratios are roughly the ratio of how common a behavior is in legitimate (green) articles as compared to potential papermill articles*. Sharing new data online is about twice as common in green articles (32%) as opposed to red or orange (17%), which approximates the ratio of 2.3x in the figure below.

Since talk data aren’t systematically captured, presentations are under-counted here. Even so, among the presentations we can verify, they appear for 2.8% of green articles but are extremely rare in red or orange articles (0.4%), leading to a ratio of 7.

So, if a newly submitted article has shared new data online, this is a decent signal that the article is not from a paper mill. However, if you detect that the authors have gone to the trouble of doing a departmental seminar or travelling to a conference to present their work, you can be almost certain that the article is not from a mill.

What This Evidence Shows

Taken together, these results do not suggest that open science practices cause research integrity, nor that the absence of such practices should be treated as evidence of misconduct.

Rather, they support a more modest but operationally useful claim: that open science behaviors function as honest signals of a researcher’s willingness to expose their work to scrutiny. As with honest signalling in biological systems, the value lies not in perfection or universality, but in the fact that these behaviors are sufficiently costly — in time, effort, and reputational exposure — that they are disproportionately avoided by actors whose work would not withstand closer examination.

For editors and editorial offices, this framing offers a useful shift in perspective. Instead of treating open science practices as binary compliance checks or aspirational norms, they can be understood as probabilistic indicators of trustworthiness. In environments where papermills and large-scale fabrication are increasingly sophisticated, signals that are difficult to fake at scale, such as meaningful data sharing, protocol citation, preregistration, and public presentation of work, provide valuable context for triage and prioritisation, even if they are never sufficient on their own.

It is important to note that the results presented here are correlations – there may be other variables that better explain these findings. For example, articles from particular countries may have higher rates of papermill activity and culturally lower rates of data sharing, such that ‘author country’ could explain a significant amount of the association between papermill activity and open science behaviors we see here. We will explore these covariates in more detail in an upcoming preprint.

(Our conclusions do seem to hold within countries as well. For example, for the 7,468 articles that generate new data and the corresponding author lists ‘China’ as their first affiliation, data sharing is 17% (130 of 772) for articles with red papermill flags, 22% (149 of 681) for orange, and 27% (1635 of 6015) for green.)

Closing Thoughts

Honest signalling theory gives us a useful lens for understanding why some practices cluster together in trustworthy research communities, while others systematically avoid visibility. What this analysis adds is evidence that these patterns are not anecdotal—they are measurable, consistent, and strongly associated with known integrity risks. In a scholarly ecosystem under increasing strain, that distinction matters.

*The calculations behind the values in the third figure are more complex than just the ratio of the two percentages – we also have to account for the probability of being from a mill, so the risk ratios are actually derived from a logistic regression of papermill status (red+orange vs green) against each open science behavior. NB these ratios should be interpreted with care: it is definitely NOT the case (for example) that half of the articles that do not share data are from a papermill.

Discussion

3 Thoughts on "Preliminary Evidence Linking Open Science to Research Integrity"

This is a very useful analysis. Thanks for doing it, and more please!

This is very interesting! Love to see good data analysis. I bet there are a lot of presentations that _could_ in theory be associated with later publications that don’t have that relationship expressed in the metadata. Seems like there’s an incentive here for publishers to ask authors upon MS submission if there are any related presentations — and of course then to make sure that relationship makes it into DOI metadata.

> Only 182 of the 6629 articles we examined were associated with a conference presentation or departmental seminar (2.7%).

This undercounts the number of research talks associated with the published literature by at least an order of magnitude. Historically, the research community hasn’t kept a record of most research talks. As luck would have it, Cassyni launched an initiative today to help universities to change this:

https://cassyni.com/pages/press/20260128-gatech

Disclaimer: Cassyni co-founder.